Introduction

Jean R. Brink

{Print edition page number: 1}

In the summer of 1981, I attended an NEH Paleography Institute at the Newberry Library led by Anthony G. Petti, author of English Literary Hands from Chaucer to Dryden, and directed by John Tedeschi.[1] I was and am fascinated by manuscripts. To satisfy that fascination and to practice my developing paleographical skills, I decided to examine all of the early modern manuscripts in the Newberry’s collection. I thought that my search for buried treasure ought to include anonymous manuscripts, such as commonplace books and paleographical documents, neither of which might be cataloged under an author or a title. So, I started with the chronological file, and I supplemented this by consulting the shelf list. Either this approach was magic, or serendipity guided the search because, using these procedures, I turned up the second part of Lady Mary Wroth’s Urania before its existence was widely known and the then anonymous Rivall Friendship.

I was immediately attracted to the language and style of Rivall Friendship. The artfully balanced clauses reminded me of Sir Philip Sidney’s Defence of Poetry and Roger Ascham’s Schoolmaster, two of my touchstones for Renaissance prose. In 1981 I read enough of Rivall Friendship to discover that there was a first-person narrative of the English Civil War and Restoration inserted into the account of Artabella’s courtship by Phasellus and Diomed.

On and off during the past decades, I have continued to check bibliographies and catalogs to see if Rivall Friendship might have been printed or even adapted from a French, Spanish, Italian, or other source. While we cannot rule out the possibility that Rivall Friendship was indeed printed under a variant title or that a source or another copy may exist somewhere, I now think it most likely that Rivall Friendship survives in only one copy, the manuscript located at the Newberry Library and cataloged as Case MS fY 1565.R52. {2}

Description of the Manuscript

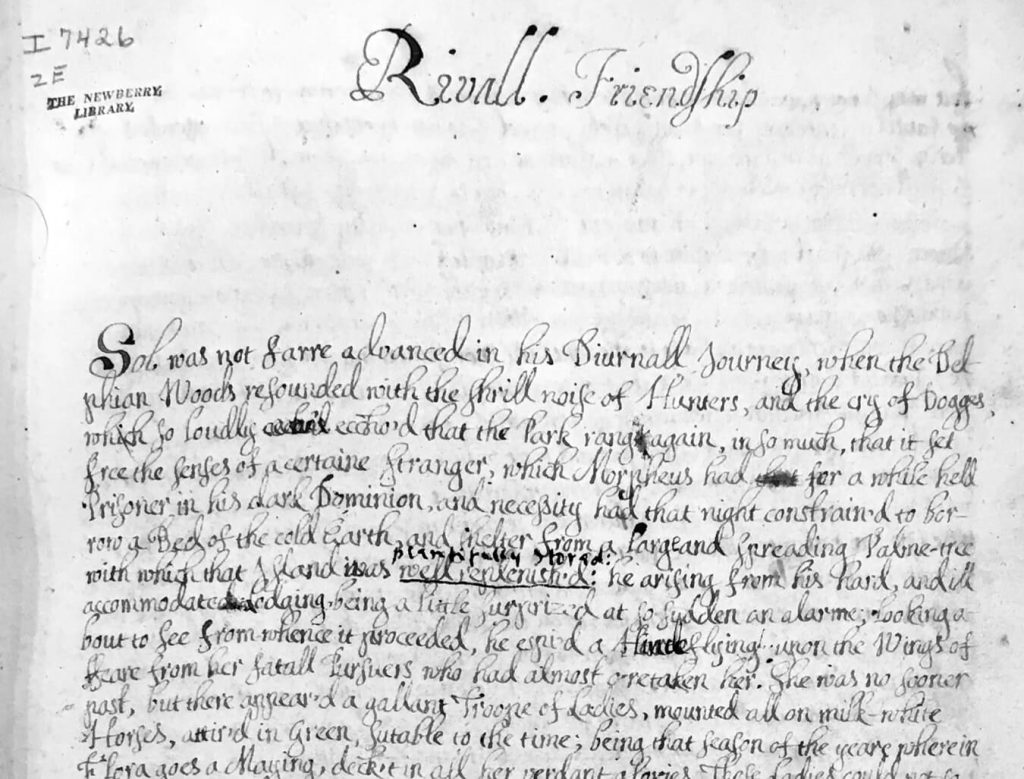

Rivall Friendship has no title page. The beginning of the narrative, “Sol was not farre advanced in his Diurnall Journey when the Delphian Woods resounded with the shrill noise of Hunters,” immediately follows the title Rivall Friendship. The call number in the upper left-hand corner suggests that this manuscript was part of a private library prior to its acquisition by the Newberry. The folio manuscript is divided into two parts: Part 1 contains 214 folios and Part 2, 165. The 379 folio pages measure 28 by 17 cm. with writing on 23 by 13.5 cm. and approximately forty lines on each page. To suggest the size and length of the manuscript, each of these folio pages transcribes roughly to two typewritten pages or four handwritten 8 × 11-inch pages.

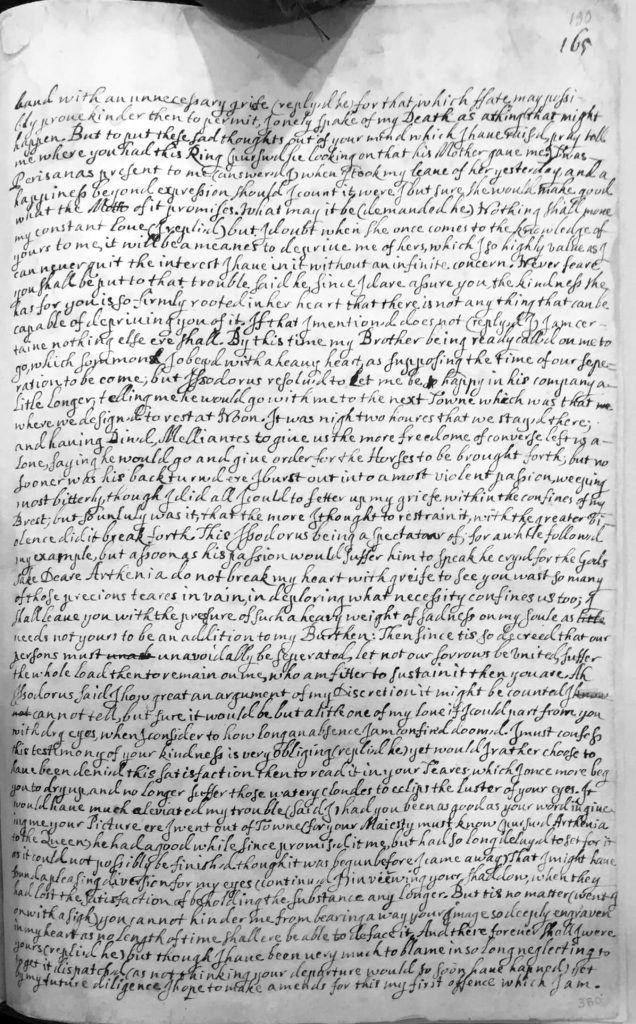

The manuscript seems to be written in two identifiable hands, both seventeenth-century italic (Figures 1 and 2); the predominant hand is written with sufficient elegance so that it was probably the work of a professional scribe. The manuscript was paginated in the upper right and left margins, but the Newberry has foliated the manuscript, and all references will be to this foliation.[2] Signatures are also noted at the bottom of the first page of each gathering until the latter part of the manuscript. Catchwords are given in the lower right corner of each page.

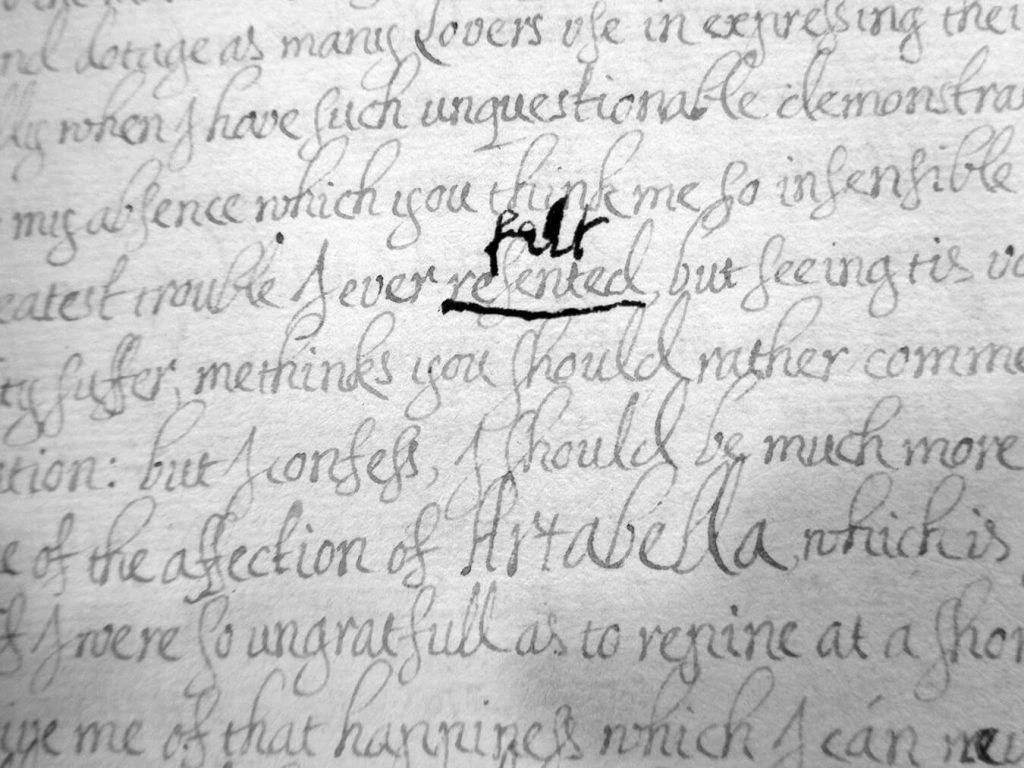

A third, primarily correcting, hand is reproduced as Figure 3. This hand uses a distinctive brown ink, underlines words or letters to be deleted, and writes above the line words or letters to be inserted. Deletions and insertions using this specific procedure are identified in textual footnotes. The changes made early in the manuscript are primarily substantive, but as the manuscript progresses, the correcting hand focuses more on spelling. The large number of substantive changes suggests that this hand is probably not scribal and that it may even be authorial. The correcting hand suggests no emendations after folio 165 v in the continuation of Arthenia’s narrative in Part 2 of Rivall Friendship.

The writing on 140 folios (1.8.94 v to 2.Cont.165 r ) is difficult to decipher because the ink seems to have faded. The manuscript was very handsomely bound in leather, and the leather cover was mended at some point. As a conservation{4} measure, the staff of the Newberry Library has taken the manuscript out of this cover and rebound the manuscript. The original binding is preserved in an attached envelope and folder.

Provenance

We know how this seventeenth-century manuscript came to be located at the Newberry Library. Rivall Friendship is one of three manuscript seventeenth-century prose romances purchased by the Newberry in the 1930s. In 1926 Frederick Ives Carpenter (1861–1925), a Spenserian scholar and a Trustee of the Library, left the Newberry his collection of printed romances with a bequest for future acquisitions. The Newberry already owned a printed edition of the First Part of Lady Mary Wroth’s Urania (1621) and in 1936 purchased the only surviving manuscript of Part Two (Newberry, Case MS fY 1565.W95).[3] The Newberry also purchased “The Lady Alice Oldfieild Her Kallicia and Philaedus” (Newberry, Case MS fY 1565.H635, formerly Phillipps MS 10596). This romance,{5} apparently a holograph, has been attributed to the royalist George Hitchcock by John D. Hurrell.[4]

In 1937 the Newberry purchased from Pickering and Chatto its third seventeenth-century manuscript romance, Rivall Friendship. The sales catalog used by Pickering and Chatto has survived and is entitled A Catalogue of / English Novels / and Romances / 1612–1837. A note indicates that Pickering and Chatto tried to ascertain if these novels and romances had been previously cataloged: “The novels and romances printed before 1740 listed in this Catalogue have been checked with the entries in ‘A List of English Tales and Prose Romances Printed before 1740’ by Arundell Esdaile, 1912.” If romances, such as Rivall Friendship, were not previously recorded in bibliographies, we have a note to that effect. The Pickering and Chatto catalog also records the existence of marginalia and enclosures. The description of Theophania (1655), for example, observes that “this copy has inserted after the title-page two printed leaves (4 pp.) ‘The Clavis to Theophania’ and contains contemporary MS. Marginalia giving a key to pseudonyms” (#761, page 82).[5]

In the Pickering and Chatto catalog, the description of Rivall Friendship is numbered 623 and appears on page 68:

623. Rivall Friendship. A MS. Romance in two parts, neatly written on 379 pages, folio (c. 1660–1690), bound in contemporary calf, back neatly repaired. 20 pounds. An allegorical romance interspersed with a few poems. As far as we can ascertain unpublished; complete mss. of these xvii. century romances must be of the utmost rarity.

The sales catalog also reprints but does not comment upon a note regarding provenance pasted inside the front cover of the bound manuscript.

After the Newberry acquired Rivall Friendship, a description was prepared for the 1937 Newberry Book List, No. 25, 4 March 1937, that reads as follows:

An unpublished manuscript of a seventeenth-century prose romance selected from Pickering and Chatto’s Catalogue no. 623 by Dr. Forsythe and recommended for purchase from the Carpenter Fund. 18 ₤{6}

On 13 March 1937, the following information and dates were added to the description recorded in the Newberry Book List:

2 parts: 214 and 165 folio pages with 40 lines to a page. Faded ink in Part 8 of Part 1 f. 188 to f.114 of Part 2. Contemporary calf binding (1650–1675)

According to the Newberry Library Book-List, which also serves as an accession catalog, the handwriting of the manuscript dates from around 1650–1675. The watermark of a horn is found throughout the manuscript of Rivall Friendship (Figure 4). Similar watermarks seem to have been used between 1665 and 1680, making it likely that the manuscript was copied near the conclusion of the dates (1650–1675) suggested by the Newberry’s analysis of the handwriting.[6] In addition, it has been possible to date the end papers around 1760. They bear Britain’s coat of arms and the garter motto: Honi soit qui mal y pense (“Shame to him who thinks evil of it,” popularly rendered as “Evil to him who evil thinks”) as a water mark with G R (George Rex) as a secondary mark.[7] It is likely that these papers were added when the manuscript was bound or rebound in the eighteenth century.{7}

External Evidence of Authorship

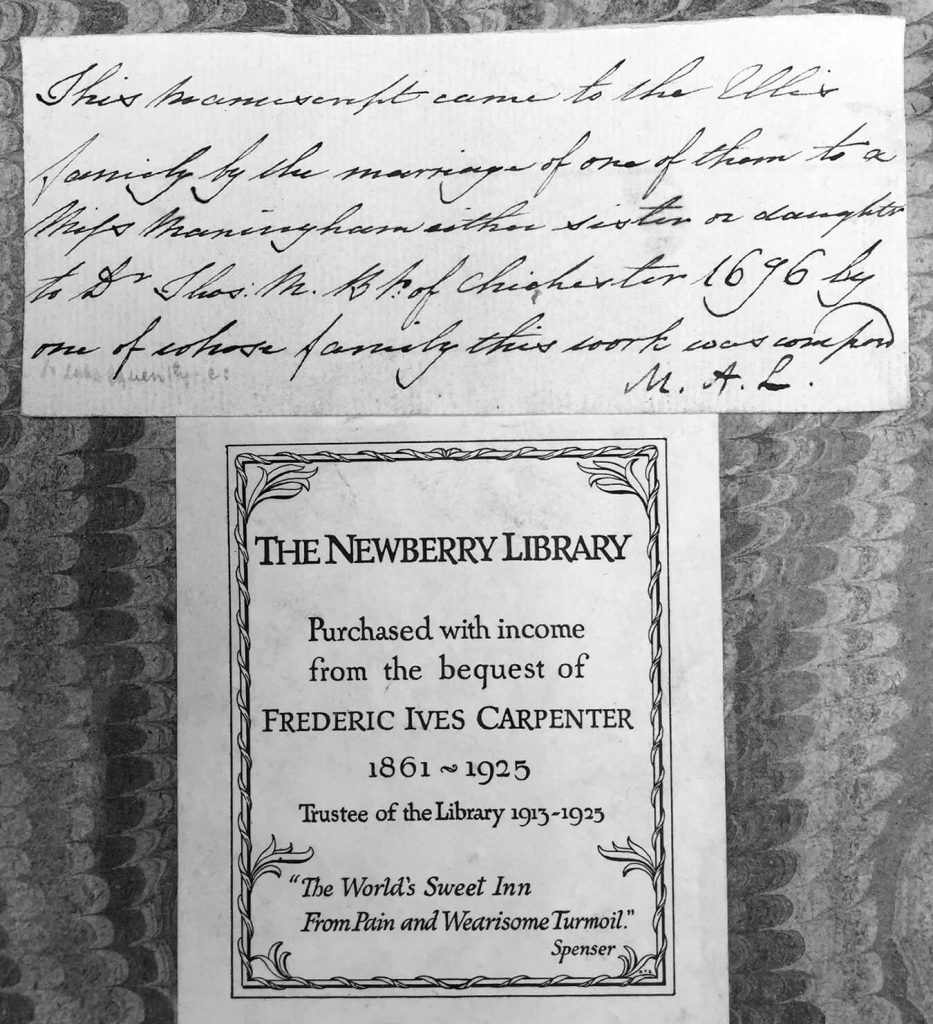

Both the Newberry Library and Pickering and Chatto, the bookseller, call attention to the note pasted inside the manuscript cover signed M. A. L. The handwriting of the note, particularly its use of a long “s,” suggests that this note was written prior to the twentieth century; it is possible that the note was pasted inside the cover of Rivall Friendship when end papers dating approximately 1760 were added to the manuscript. M. A. L, who is neither a Manningham, nor an Ellis, has yet to be identified. M. A. L. states suggestively that the manuscript became the property of the Ellis family because of a marriage into this family of a Miss Manningham.

This manuscript came to the Ellis family by the marriage of one of them to a Miss Manningham either sister or daughter to Dr. Thos: M. Bp of Chichester 1696 by one of whose family this work was composed. (See Figure 5.)

Although not hitherto recognized, this clue to authorship indicates that the manuscript passed through the female line.

Thomas Manningham’s will survives, and in it he specifies that his books, scribal manuscripts, and other papers will not pass with his major estate to his eldest son.[8] He explains that he has departed from primogeniture and bequeathed his books and papers to another son, who has pursued a career in the church. One of Thomas Manningham’s family wrote the manuscript, but unlike his books and other papers, Rivall Friendship descended to a Miss Manningham who married into the Ellis family.[9] Genealogists exhibit little interest in female descendants because they do not retain the family name and can be difficult to trace. Even George Agar Ellis, who edited a collection of the Ellis family letters and who included a genealogical chart of his family history, ignores the descendants of women except in the case of his own female ancestor.[10]

Dating

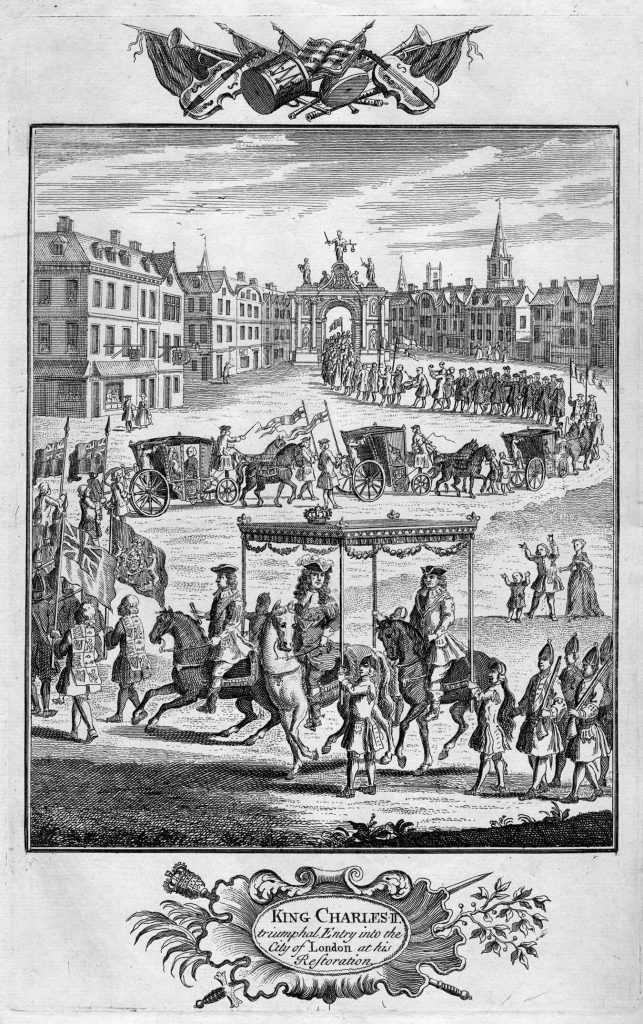

Thomas Manningham is identified by name in the one clue to provenance, and so we need to refine the dating so as to eliminate the possibility that Rivall Friendship was authored by his offspring. As noted above, the Newberry Book-List dates the handwriting to 1650–75. Rivall Friendship was written after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 because his procession into London is described at length in Book 8 of Part 1. In Part 2, there is also a likely reference to James Butler, Duke of Ormond, who served as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, 1660–69 and 1677–85.{9} Because Thomas Manningham’s two eldest sons were not baptized until 1683 and 1685, they could not have authored Rivall Friendship unless it was written in the eighteenth century. The extensive commentary on the Civil War and the entertainments marking the progress of Charles II into London would have become less interesting politically as time passed. Taken together, the handwriting and the political references suggest that Rivall Friendship was completed prior to or during the last quarter of the seventeenth century, sometime between 1665 and 1685. For these reasons, it seems likely that Rivall Friendship was written by someone belonging to the immediate generation of Thomas Manningham rather than by his offspring, i.e., a sister rather than a daughter.

Thomas Manningham

The authorship of Thomas Manningham, the only person referenced in the note concerning provenance, must be seriously considered.[11] Manningham (d. 1722) was born in St. George’s Southwark, the son of Richard Manningham (d. 1682), rector of Michelmersh, Hampshire, and Bridget Blackwell. Little is known about Richard Manningham except that he was sequestered during the Civil War and lost Bradbourne House, the family estate. In spite of these financial hardships, Richard managed to give his son an excellent education at Winchester and at New College, Oxford, where Thomas matriculated with a scholarship on 12 August 1669. In 1681 Thomas was presented with the comfortable living of East Tisted in Hampshire. Anthony Wood describes him as “a high flown” preacher and “passionately desirous to collect himself, to be known to few, and to be envied by none.”[12]

There are indications that Thomas Manningham was confident of his own worth. When Queen Anne was ill and confined to her chamber, it was suggested that he pray in an adjoining room, but he refused saying that “he did not chuse to whistle the prayers of the church through a key hole.”[13] He is described by Donald Gray in his Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article as a Hanoverian Tory with high church sympathies and as intolerant of dissent.[14] After he{10} was appointed Bishop of Chichester in 1709, he found that Whigs predominated in his chapter and reported to the archbishop on the dangers of dissenters in his diocese. He dutifully supported the succession laid down by the Act of Settlement rather than the Jacobite cause. In 1715, he was one of the bishops who signed a declaration condemning the Jacobite rebellion of that year.

His published sermons indicate that he had the background and learning but not the sense of humor to have written Rivall Friendship. He describes with obvious distaste the Interregnum as a period when innovation was rampant, and “[e]very conceited Politician sent forth his new System of Civil Government: Every illuminated Brother, his new Models of Christs Kingdom: every one was for erecting an Empire for himself, and a Platform wherein his own Imaginations might rule.”[15] More an Anglican than a classicist, Manningham disparagingly dismisses Platonists as “a Sect of People who were generally of a soft and Amorous Nature, who plac’d their Happiness in the Speculation of Ideas; and who rarely consider’d God, as a Righteous Punisher of Sin, but chiefly as a most amiable Being for them to contemplate; they usually entertain’d very good Opinions of themselves, and of their own Perfections.”[16]

Manningham’s attitudes toward wit also make his authorship of Rivall Friendship unlikely. In A Sermon Preached at the Hampshire Feast on Shrove-Tuesday, February 16, 1685/6, he states that “Man was not made for Levity, but for grave and weighty Affairs.”[17] He is concerned about “lasciviousness and its pervasiveness,” describing it as the “very Character of the Age . . . the nauseous repetition of almost every great Table, and every private Club; ’tis the Song and Poetry of the Young, and the filthy Jest of the Aged.” His views on wit and comedy suggest that some passages in Rivall Friendship might have offended his sense of decency: “We must not countenance the least Uncleanness by an ambiguous word, by a complyant Smile, by a wanton Metaphor: but when others talk Lewdly, let us pray inwardly; what they call Comedy, let us represent to our selves as the deepest Tragedy.” Thomas Manningham does not appear to be the sort of{11} person who could envision Phasellus’s swooning for love, like Chaucer’s Troilus, and then sticking a mysterious weed up his nose to hasten his demise. Likewise, Phasellus’s suicide would be unacceptable to Bishop Manningham.

If we turn to Manningham’s personal life, he and his wife Elizabeth (1657–1714) had ten children. When Elizabeth died in 1714 at age 57, Manningham buried her in Chichester Cathedral and wrote an epitaph emphasizing her godliness:

She was comely in her person, meek in her temper, most humble in her behaviour, prudent in all her actions, and pious through her whole life. She had a mind improved by a good share of useful learning, but that appeared only in her judgement. She never took one step into the vanities of the world; but . . . she employed her time chiefly in the exercise of her constant devotion, and in giving her children their first instructions in Religion.[18]

Judging from the tone of Elizabeth’s epitaph, Thomas was not an advocate for female learning. He valued Elizabeth’s docility and commented that her mind had been improved by “useful learning,” thus suggesting that she was brought up to be a good housewife rather than liberally educated in the classics. Manningham’s assertion that [her learning] “appeared only in her judgement” suggests that he would have been unlikely to encourage either his wife or his daughters to write a romance.

Of Thomas and Elizabeth’s ten children, five are identified in Thomas Manningham’s will: three sons, Thomas, Richard, and Simon, and two married daughters, Mary Rawlinson and Dorothea Walters.[19] Of these two daughters, it was the elder, Mary Manningham Rawlinson, who inherited Rivall Friendship. Mary Manningham married Reverend Dr. Robert Rawlinson of Charlwood in Surrey, becoming his second wife in 1716; she did not die until 1752 in the parish of St. Leonard, Shoreditch, on October 24. Her will dated August 6, 1750 was proved on October 26, 1752.[20] Her only heir was a girl named Mary, who was the younger half-sister of Sir Thomas Rawlinson who became Lord Mayor of London in 1754.[21] This Mary Rawlinson, whose mother’s family name was{12} Manningham, married Francis Ellis, a well-to-do woolen draper. He was born on October 4, 1709, and married Mary at St. Michael’s, Cornhill, in 1736/7.[22] Mary (Rawlinson) Ellis and Francis Ellis are described as having had two sons, Robert and William, who died without issue.

In summary, the physical evidence of the manuscript, the Newberry’s dating of the handwriting and the likely dating of the watermarks in the paper as well as the provenance outlined in the note signed M. A. L suggest that Rivall Friendship was written by someone belonging to Thomas Manningham’s generation. Thomas Manningham himself had the rhetorical skill to have written Rivall Friendship, but his temperament, as reflected in his published sermons and as assessed by his contemporaries, indicates that he is unlikely to have been the author of this seventeenth-century prose romance. Based on its provenance, specifically its transmission through the female line, it seems probable that the author of Rivall Friendship was a woman belonging to Thomas Manningham’s own generation.

Internal Evidence:

Gender, Narrative Structure, Psychology

The author of Rivall Friendship articulates anti-patriarchal positions on marriage and inheritance. These proto-feminist views do not necessarily suggest the gender of the author, but we might expect the experiences of educated women to lead them to question gender hierarchy and the impact of primogeniture on inheritance laws. In Part 1 of Rivall Friendship, the conventional dominance of men over women in marriage is questioned: “not that I account all wemen slaves, or think all men are Tyrants to their Wives; but if they are not they are at least capable of becoming so when ere they please” (1.7.83 v ). In Part 2, the author comments on the contemporary inheritance practice of favoring men over women. In Delphos, we are told, there is the practice “not to be found in any kingdom of the world but this” of giving the “scepter in succession to the eldest child, preferring the daughter before the son, if she be born first” (2.4.164 r ).

In addition, the events in Rivall Friendship are for the most related through the eyes of women. After an omniscient author briefly sets the stage at the beginning of the action, the two major narratives are narrated by women. In Books 1–4 of Part 1, Celia, a companion and attendant to Queen Ermilia, relates the story of Princess Artabella (Queen Ermilia’s mother) and her courtship by Diomed and Phasellus. This narration is introduced by Celia to explain to Arthenia, who was washed up on the shores of Delphos disguised as a man, why there is a law on Delphos condemning to death lowborn men who enter the palace grounds{13} without the queen’s permission. In Books 5–8 of Part I, Arthenia, who becomes the next female narrator, explains to Celia and Queen Ermilia how she came to be washed up on the shores of Delphos. She uses first-person narration to relate her own history which she describes as inextricably involved with the English Civil War:

I was yet but an infant, when I beheld my Country cruelly embroil’d in a Civill, and most unnaturall War; and terribly wasted, and destroy’d with Fire and sword, not of strangers, but even of those very People she had bred . . . so much dependance has my owne perticuler story on this Warre, that I cannot give a perfect account of my misfortunes without relating it; since my unhappiness derives its originall from that of my country. (I.5.61 v )

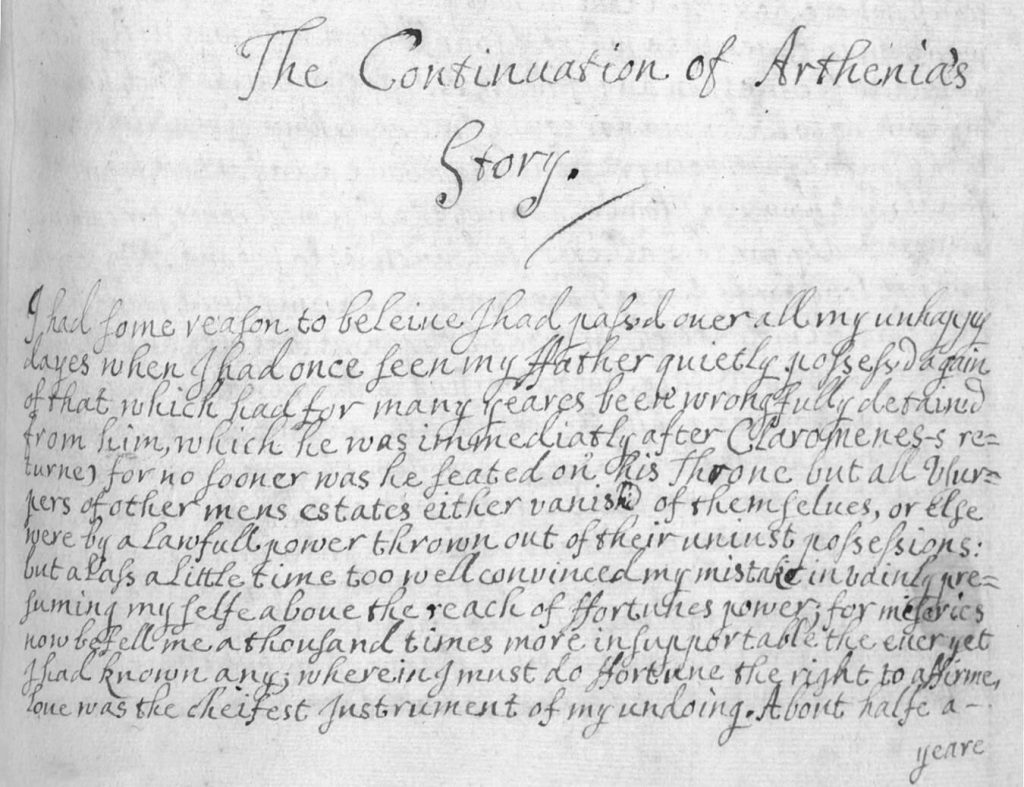

The narrative structure of Part 2 of Rivall Friendship employs a similar pattern of female narration. Books 1–4 continue the account of Artabella’s story and are narrated by Celia. Arthenia continues her history now situated in Restoration London in a section labeled “The Continuation of Arthenia’s Story.”

Perhaps even more telling than the prominence of female narrators, there is persuasive psychological evidence that the author of Rivall Friendship was a woman. Both narratives portray Artabella and then Arthenia as victimized women. These women, in spite of Artabella’s protestations to the contrary, are not brought down by fortune or fate; rather, they suffer misfortune because they are betrayed by their lovers. Not only does Phasellus betray Artabella to advance himself by marrying Queen Oriana, he also deceitfully persuades his best friend Diomed to relinquish his suit for Artabella. An unmitigated villain, Phasellus arranges for the kidnapping of Artabella by his henchmen and imprisons her. After conveniently disposing of Artabella, he then tricks Queen Oriana into marriage by pretending that he is her father’s choice. Likewise, in Arthenia’s history, the actions of Loreto are devoid of conscience where women are concerned. Even though he proclaims his eternal devotion to Arthenia, he woos one woman for her fortune and then marries a wealthy heiress. Even after this marriage, he continues to pursue Arthenia, presumably to seduce her. In Part 2, Arthenia is pursued and compromised by Issodorus, who is depicted as manipulative and mendacious. Arthenia’s story is not finished in the present manuscript, but it seems likely that Issodorus is responsible for her being abandoned and washed ashore in Delphos.

Clues in the Historical Allegory

The historical allegory also invites us to associate Rivall Friendship with the Manninghams and their family home in Kent, Bradbourne House (Figure 6). In Part 1, Book 5, Arthenia describes her birth as “neer to the Citie Agrigentum” (1.5.62 r ).{14} When the city of Agrigentum appears in Arthenia’s history of the Civil War, the topical details identify Agrigentum as East Malling, where Bradbourne House, the Manningham family estate, is situated. We are also told that Agrigentum is located in the province of Nota (Kent) and that in May 1648 it served as a place of temporary retreat for the forces of the royalist Gerandus (George Goring, first Earl of Norwich). When the parliamentarian general Faragenes (Sir Thomas Fairfax) approached, Gerundus sought sanctuary for his troops in Enna (Maidstone) and afterward ferried his troops across the river to Colchester (1.6.72 v –73 r ).

The dating of the manuscript, its transmission through the female line, the pervasive feminist critique of patriarchy by female narrators, the prominence of victimized women abused by unsatisfactory and disloyal lovers, and clues in the historical allegory, specifically the correspondence of the setting of Agrigentum to East Malling, the Manningham family seat, suggest that the author of Rivall Friendship was very likely to have been Bridget Manningham, the older sister of Thomas Manningham, a Caroline and Hanoverian bishop, and the granddaughter of John Manningham, the diarist who recorded performances of Shakespeare’s plays.

Manuscript Transmissions:

The Sidneys and the Manninghams

Sir Philip Sidney is a canonical author whose works were printed in edition after edition. Manuscripts, however, differ from printed texts. The history of the manuscript of the Old Arcadia illustrates the vulnerability of all manuscript{15} texts. However popular the printed Arcadia unquestionably was, the manuscript of the Old Arcadia remained unprinted for over three centuries. In 1926, it was printed by Albert Feuillerat for Cambridge University Press, but the Old Arcadia did not receive an accurate text until 1973, fifty years later.[23] Sir Philip’s brother, Robert Sidney, Earl of Leicester, also authored a manuscript collection of poems that was not published until the twentieth century.[24]

Lady Mary Wroth printed the first part of the Urania in 1621, but the second part, like her uncle’s Old Arcadia, was preserved only in manuscript.[25] Moreover, if Wroth had not printed the first part and so insured that her authorship of the Urania was widely known, then the authorship of the second part, surviving in one holograph copy at the Newberry, would have been unclear. This manuscript has no title page and no indication of the author’s name. Thus, if it were not for the 1621 printed edition of Part 1, Part 2 of the Urania, like Rivall Friendship, would be an anonymous text preserved in a single manuscript at the Newberry Library!

Bridget Manningham belonged to a family, like that of the Sidneys, who valued authorship and preserved manuscripts. She was the granddaughter of the witty John Manningham, member of the Middle Temple and celebrated Jacobean diarist. John Manningham’s diary was not printed during his lifetime; it was preserved by the Manningham family, an indication of familial respect for manuscripts. The Diary passed into the British Library (becoming Harleian MS 5353) before it was finally edited and printed in 1868.[26] Significantly, property records safely stored away in a muniment room are more likely to survive than diaries, memoirs, or literary manuscripts. The Manningham family shared the Sidneys’ values, preserving the manuscript Diary of their ancestor until it was printed generations later. Bridget Manningham’s Rivall Friendship, like John Manningham’s Diary, was preserved and seems to have passed through the female line into the Ellis family until it was sold to Pickering and Chatto, the booksellers, who sold it to the Newberry Library. {16}

Bridget Manningham

To begin the history of the literary Manninghams, we can start with John Manningham, the diarist and frequenter of Shakespeare’s plays, who grew up in Fen Drayton, Cambridgeshire.[27] After his father Robert died in 1588, he became the adopted son and heir of his relative, Richard Manningham of Kent, a retired member of the Mercers’ Company of London. This Richard Manningham was prosperous enough to have purchased the fine manor house of Bradbourne in East Malling, near Maidstone in Kent. John Manningham named his first son Richard (1608–1682) in honor of his foster father, whom he described as his father-in-love. He married Anne Curle, the sister of Edward Curle, his chamber mate at the Middle Temple. Curle’s father, William, was a retainer of Sir Robert Cecil and also quite prosperous.

John Manningham’s son Richard Manningham married Bridget Blackwell of Broxbourne, Hertfordshire in 1636. In 1637 Bridget gave birth to her first child, Anne Manningham, who seems to have been named Anne after her husband’s grandmother. Anne is not mentioned in her father’s will and so is likely to have predeceased her father. Bridget, who was her parents’ surviving daughter, was named after her mother. In May 1638, Richard became the Rector of Michelmersh, Hampshire, a parish located near property belonging to the Sidney family. He retained that position until he was sequestered in 1646. His sequestration may account for his having had the leisure to oversee his daughter’s extraordinary education. She is familiar with Plutarch as well as Shakespeare and knows the fine points of classical mythology. When she uses “admire” as a synonym for “wonder” (rather than adore or appreciate), she makes the kind of connection a classical scholar might make.

During the Interregnum, Richard Manningham lost Bradbourne House in Kent to Thomas Twisden.[28] Thomas was the younger son of Sir William Twisden of Roydon Hall, East Peckham, and, more significantly, the brother-in-law of the Cromwellian officer, Matthew Thomlinson. Under Cromwell’s influence, Twisden was installed as Recorder and Town Clerk of Maidstone and built up a successful law practice during the Interregnum. With his fortune, he purchased Bradbourne, the Manningham family estate. It seems unlikely to be a coincidence that one of the female figures featured in the Civil War sections of Rivall Friendship has a change in financial fortunes that causes her fiancé to repudiate her, break the engagement, and cancel the wedding plans.

After the Restoration, Richard Manningham was restored to his rectory at Michelmersh, which he held until his death on June 12, 1682, but he never{17} regained Bradbourne House. His will was probated the following November. In it, he mentions three sons: Richard, Nicholas, and Thomas, later Bishop of Chichester, and a daughter, Bridget. We do not know when Bridget Manningham was born; she seems never to have married and later entrusted Rivall Friendship to her niece, Mary (Manningham) Rawlinson, Thomas Manningham’s daughter. There is thus substantive external evidence, confirmed by documentary records, that Rivall Friendship was authored by a member of the Manningham family who belonged to Thomas Manningham’s generation and plausible internal evidence that this was the work of Bridget Manningham who was living in 1682.

Literary and Historical Contexts

Rivall Friendship is remarkable in two significant respects: first, Bridget Manningham juxtaposes Artabella’s romance with Arthenia’s history explicitly labeled a history in her text, giving this unprinted manuscript text a pivotal position in the transition from the early modern romance to what will later be called the novel.[29] Second, Rivall Friendship, a post-Civil War romance, examines proto-feminist issues, such as patriarchal dominance in the family and marriage, in an almost modern manner. The literary transition from the romance to the novel may be related to this feminist thrust because after the English Civil War, social norms were in flux in a way that they were not to be again until after World War I.[30] In consequence, Bridget Manningham depicts the romance of Artabella as giving way to the verisimilitude of Arthenia’s narration of battles in the Civil War and to Restoration courtships in which love is subordinated to the interests of money and property. All of this is handled with stylistic elegance. Passionate feelings pour out in finely balanced sentences with an insistent parallelism.

In Artabella’s romance, birth is of the utmost importance. The female protagonists, Artabella and Oriana, are both princesses and intensely aware of their{18} rank and position in society. Diomed, the romantic hero, spells out his lineage in some detail, explaining that he is Prince Lucius and descended from Augustus Caesar and that he is by birth heir to a kingdom (1.2.28 r ). Prince Lucius has disguised himself as Diomed so that he can win renown and merit, wanting to be worthy of ruling an empire because of “vertue” as well as “birth” (1.2.28 v ). Only in retrospect does it seem important that we are told that Diomed’s friend “was not born a Prince” (1.2.28 v ).[31]

In the class-structured society of Artabella’s romance, obedience to the father or to parental figures is required because familial bloodlines are the source of status and rank. Unaware of his noble birth, Princess Oriana tells Diomed, “if you can gain Achemenes [her father] to favour your desires, I shall not oppose them, for his Will must ever be my Law” (1.2.35 r ). Manningham portrays both Oriana and Artabella as acknowledging the importance of their fathers’ wills in determining whom they should marry. To emphasize that obedience and duty are patriarchal obligations, Manningham makes King Achemenes and his brother Menzor unmarried widowers so that no wives complicate the issue of paternal authority. Even before Achemenes and Menzor are aware of Diomed’s birth, his military prowess makes him the preferred husband for the daughters of both patriarchs. The villainy of Phasellus is not immediately apparent, and we, as readers, sympathize with Artabella’s attraction to him until he betrays Artabella and then tricks Oriana into marriage.

Oriana’s fate tests the legitimacy of patriarchy. After marrying Phasellus whom she despises, Oriana contemplates suicide in the “face of Phasellus” because he will not release her from “that engagement Achemenes laid on her” and plans to stab her own heart “for its disobedience to the King my Fathers will” (2.3.143 v ). Oriana explains to Diomed that Phasellus had continued “still urging me with my Duty, and my Engagement to Achemenes, which (he said) if I would have a Dispensation from, I must fetch him from the Dead to absolve me.” (2.4.154 r ). When Phasellus, the villain, argues in favor of paternal authority, it becomes clear that Manningham is using the convention to interrogate patriarchy. When Oriana later learns that Phasellus has tricked her into marriage by using her filial obedience against her, she repudiates her filial duty as “blind obedience to my Fathers Will” (2.3.143 v ) and still considers suicide but only as a means of depriving Phasellus of her crown. Far from being rewarded for her{19} “blind obedience to her Fathers Will,” it is clear that she would have fared better if she had followed her own heart; she dies a virgin and her cousin’s son inherits the crown of Persia.

Artabella’s story tests patriarchal authority in another way. In contrast to Oriana, who follows what she thinks is her father’s directive, Artabella ignores her father Menzor’s preference for Diomed and commits herself to Phasellus. When she later discovers the full extent of his villainy, she exclaims:

tis onely unhappie Artabella that has been the cause both of her owne misfortunes, and poor Prince Lucius’s too; for had I not so blindly ty’d my heart to a fond dotage on Phasellus, I had not (questionless) oppos’d my Father^’s^ Will. (2.4.158 r )

Artabella thus recognizes that her “fond dotage on Phasellus” was mistaken and that she should not have opposed her “Father’s Will.” In contrast, Oriana marries Phasellus because it seems to be her duty, but after both Diomed and Phasellus die, she does not remarry. Artabella, who disobeys her father Menzor, later marries King Alcander of Delphos, and lives happily with him. It is their son who inherits Achemenes’ and Oriana’s throne.

The moral of Artabella’s romance is thus far from a simplistic endorsement of patriarchy. Manningham shows that Oriana’s efforts to follow her father’s behests make her susceptible to the machinations of the villainous Phasellus. Artabella, in contrast, pays lip service to her duty to her father while she is deceiving him. In spite of Artabella’s rejection of her father’s will, she is rewarded. Her life ends happily when she is united in marriage to the worthy Alcander. Prior to the marriage, Artabella tests his fidelity by entering a convent while he tests himself by going on a grand tour seemingly structured by visits to eligible marriage partners. Alcander passes his test with flying colors; his loyalty assured, he marries Artabella, and they live happily ever after on Delphos.

If Artabella’s romance interrogates patriarchy, it all the more absolutely reifies the importance of class. Diomed, who is really Prince Lucius, represents all that is admirable in a friend, lover, and warrior. Artabella, presumably as a result of her experience with Phasellus, establishes a law in Delphos condemning to death lowborn unauthorized male intruders into the royal presence.{20}

This law prohibits all Persons (Princes, and Ambassadours excepted) from coming into the Queens presence, or within the precincts of the Palace (upon any account whatever) under pain of Death, without a Warrant first obtain’d from the Queen, sign’d with her owne hand, and seal’d with the Privie Signet. (1.1.3 v )

This law, which cannot be altered without the consensus of all the nobles, would have allowed Diomed, born a prince, access to the Palace and banned the ignoble Phasellus from its precincts.

Manningham seems to have imagined the two narratives together as part of a whole. She links the romance of Artabella with the history of Arthenia in a striking in media res beginning in which a young man sees a troop of ladies, attired in green, pursuing a hind. A young woman (later revealed to be Celia) catches sight of him and urges him to fly, but before he can respond, the queen and her ladies arrive. Queen Ermilia asks what “ill Fate hath conducted thee hither to thy Death,” but it is not until the next day that Arthenia (disguised as a man) learns the nature of her offense. Celia explains that there is a law condemning lowborn men to death if they enter the palace grounds without royal authorization. Rather than protesting his fate, the unknown person asks that his death may occur as soon as possible. He is saved from death only when an ambassador reveals his identity as a woman named Arthenia! This dramatic introduction links the narratives of Artabella and Arthenia, which are then related retrospectively by two female narrators, Celia, who relates Artabella’s romance, and Arthenia, who tells her own history. Arthenia’s presence in the opening scene and her position as principal auditor for Celia’s account of Artabella’s romance demonstrates that Manningham wants the reader to link these two narratives. The generational divide between Artabella’s romance (its narrative concerns events occurring before the present Ermilia, Queen of Delphos, was born) and Arthenia’s history reinforces the reader’s perception of Arthenia’s history as similar to the novel, an emerging literary form.

The English Civil War and its aftermath is the setting for Arthenia’s history. This distinctly royalist narrative begins with a retelling in classical dress and personages of battles in the Civil War, describes the execution of Charles I (Clearchus), and concludes with a description of Charles II’s (Claromenes’s) progress into London for his coronation (Figure 7). In Part 1, Arthenia fends off the advances of a rake named Loreto. In the second part of Arthenia’s history, set in post-Civil War London, the relationship between the sexes has changed into the kind of battle depicted in Restoration comedies. In Part 2, Issodorus explicitly justifies his romantic deceits as a strategy to win the war between the sexes:

But why Madam should you count that so crimenall in matters of love (continu’d he) which in War is daily practiced uncondemn’d; for you well know tis allow’d to those who besiege a Towne to have recourse to strategems to get, what by force, or treaty they cannot hope to gain, and using that litle artifice to inhance the value of my love, by endeavouring to perswade you ’twas sacred to your selfe alone without any others having had an interest in it. (2.Cont.186 r )

The narrative shifts from a description of the battles of the English Civil War to accounts of embattled Arthenia’s attempts to withstand advances from Loreto in Part 1 and Issodorus in Part 2.{21}

The difference between the romance of Artabella and Arthenia’s history is suggested by the handling of war and kingship, themes present in both narratives. In Part 2, Book 3, Mexaris, Diomed’s squire, supplies a tribute to Diomed’s prowess that identifies him as the hero of a romance:

Though the Scythians trymph’d over the life of Achemenes (said Mexaris) they cannot boast they did so over my Masters; for after he had died their Fields with the blood of thousands of them, subdu’d the whole Kingdome, taken Oruntus Prisoner and reduced him to that estate as to impose on him what Conditions he pleas’d, established a perpetuall League of Amitie between both the Kingdomes, and returned a victorious Conquerour into Persia. (2.3.134 v )

The exaggeration of Diomed’s having “died their Fields with the blood of thousands” in Artabella’s romance can be juxtaposed with the more realistic descriptions of war in Arthenia’s historical narrative:

Having perform’d all the duties of a Generall he gave the onset, charging so fiercely on the right wing of the enemy, consisting of Faragene’s Cavalarie in the van, and the Corsicans in the Reere, that they fell back in such disorder on their owne infantry that they broke their ranks, treading many of them under their horses Feet. (1.5.65 v )

Arthenia explains that the cavalry became so disorganized that they rode down their own infantry while Mexaris’ romanticizes Diomed’s having “subdu’d the whole kingdom” of Scythia.

Mexaris supplies an account of Diomed’s death and that of his rival and erstwhile friend Phasellus (hence the title Rivall Friendship). Concluding his description of Diomed’s death with an elegant antithesis, he observes: “He there (instead of those Tryumphs his renouned Valour merited) found his death; not from the sword of a professed Enemy, but from the secret treachery of a perfidious Friend” (2.3.134 v ). Rhetorical polish of this kind is not absent from Arthenia’s history, but it is rarely used to describe battles or laud the heroic achievements of a protagonist; it is reserved for the philosophical core of the narrative, the speeches and reflections of Clearchus (King Charles I).

Manningham’s Charles is endowed with reason and insists that reason, rather than “humour” should monitor his actions, particularly in dealing with the Senate:

I will not, to gratifie my owne humour, deny any thing that my reason allows me to grant, so, on the other side, I will never yeeld to more then Reason, Justice, and Honour obliges me too in refference to my Peoples good. I’le study to satisfy the Senat in what I may, but I will never for feare, or flattery gratifie any Faction how potent soever. (1.5.67 v ){23}

Like Aphra Behn and Margaret Cavendish, Bridget Manningham is a royalist. Charles I defends not divinely appointed kingship but law and liberty. He is portrayed as eloquently affirming the importance of reason: “But though I am not so confident of my owne abilities as not willingly to admit of the Councells of others; so neither am I so doubtfull of my selfe as brutishly to submit to any mans Dictates: for that were to betray the soveraignity of Reason in my Soule, and the majesty of my Crowne and Dignity, which gives me power to deny what my Reason tells me I ought not to grant” (1.6.67 v ). In spite of this emphasis upon reason and law, Manningham fully accepts the premise that a king’s position sets him apart from his subjects and that they owe him obedience: Charles also remarks: “they may remember, they set in Senat as my subjects, not superiors; call’d thither to be my Councellours, not Dictators” (1.5.67 v ).

Like Arthenia’s history, Artabella’s romance also treats the topics of reason and absolute kingship. After his proposal of marriage to Achemenes’s daughter Oriana is rejected, Octimasdes of Scythia invades Persia and loses his life. His brother Oruntus becomes king of the Scythians, and he, too, invades Persia, but is vanquished by Diomed and the Persian army. Oruntus is so wicked, so much the epitome of an evil king, that he poisons his own daughter for facilitating Diomed’s escape from prison. Diomed, who now has control over Oruntus’ fate, acknowledges the absolute power of kings:

I am not ignorant Madam of that power which belongs to Kings; I know it absolute, not to be controul’d by any; but I know withall that Good and just Princes never make their Will their Law; none but a Tyrant does do soe, and such your King shew’d himselfe, when he with so much inhumanity murther’d his onely Daughter; had he put her to death Legally, he had been much more excusable. (1.4.57 v )

Here Diomed seems to take the legalist position too far in stating that Oruntus’ murder of his daughter would seem “more excusable” if it were within the law. It is noteworthy, however, that in her treatment of kingship Manningham uses the principles of reason and law to connect Artabella’s romance with Arthenia’s history.

The romance of Artabella is set in ancient Persia and makes use of conventional romance motifs including kidnapping by sinister figures, a rescue which leads to another kidnapping by pirates, an oracle, a sojourn at the temple of Diana, a deadly potion which simulates death, passionate affirmations of love by a lover likely to die if rejected, and even a romantic hero, Diomed, who turns out to be a descendant of Augustus Caesar. Arthenia’s first-person narrative, which looks forward to the novel, rejects the marvelous and instead relates the history of battles in the English Civil War and then depicts the difficulties faced by a single woman as she negotiates the drawing rooms, public houses, and communal gardens of Restoration Britain. {24}

Manningham’s description of the Restoration court and its “ruffling braveries” displays her talent in setting a scene:

the ruffling braveries of the Court with all its perfum’d Gallants who spend their time in nought but in debauching each other, or else in studying which way they may easiest beguile poore woemen by their trifling courtships; pretending much of love but intending nothing save their delusion or abuse. (2.Cont.165 r )

In Arthenia’s history, once the battles are concluded, little happens. Neighbors visit and become friends. Arthenia and Bellamira eat at the public house, Lavernus. After the war, except for the triumphant progress of Charles II into London, Arthenia’s history turns upon her courtship by two suitors: Loreto, who marries for money seemingly under parental pressure, and Issodorus, who lies to Arthenia about his dead wife, and whose friends seem to think that he also needs to marry for money. Restoration Britain is a world in which the possession of money and property, or lack thereof, has become a serious matter.

In Artabella’s romance, Bridget Manningham is quite scrupulous about maintaining the verisimilitude of historical detail. Unlike more fantastical romances that feature monsters, giants, and magic, this romance aspires to a level of probability in its historical and geographical details. Artabella’s uncle, the Persian king Achemenes corresponds to an historical Achaemenes, the possibly legendary founder of the Persian dynasty in the seventh century BC.[32] When Artabella is abducted, she is transported across Bactrian sands at night to Zarispe by the Caspian Sea. These geographical details are confirmed by Peter Heylyn’s contemporary atlas.[33] Plausible foreign customs are also introduced. At Delphos, Artabella and her company dine not on tables but on carpets (1.2.39 v ). Some elements in Artabella’s romance, such as the pirates, mysterious potions, Delphic oracle, and becoming a votary of Diana’s, are also conventional in heroic romances by Philip Sidney, Robert Greene, and others, and may have been influenced by Heliodorus’s Aethiopian History which was translated from the Greek in 1577. {25} [34]

For Arthenia, Manningham creates a very different world from that of Artabella. Money and property are more important than class in Restoration Britain. Arthenia is not royal; she reports that she was born into “a Family noble enough” (1.5.62 r ) and assures her listeners that she does not want to promote herself by calling attention to the deeds of her ancestors; it is her own virtue and deeds that are important. She also reveals that she is not an authority on the Civil War, since she was a child when it began, but adds that she has educated herself as to its history. Arthenia’s “misfortunes,” her loss of fortune and property, resulted from the Civil War.

Multitudes were imprison’d, and compell’d to purchace their liberties at such excessive ransomes, as prov`d the ruines of their families. Many others who might have boasted larg Possessions (either left them by their provident Predessessors, or gain’d by their owne laborious industry) suddenly torne from them, their houses rifled, and their whole estates confiscate to the Senats use. (1.5.68 v )

She dwells poignantly on the fate of well-to-do royalists when “divers who were wealthy to a superfluity, in the space of one poore day have been reduced to such necessity, as that they have not known where to seeke their next nights Lodging” (1.5.62 r ).

In Restoration England, the fate of a single woman without fortune is described by Marione, a friend who warns her to make an advantageous marriage because after her parents’ death, her condition will become “deplorable . . . destitute of Friends, support, or maintenance; subject to all the blowes of Fortune, and miseries that necessity (that cruell Mistress) can overwhelme you with” (1.7.86 r ). Arthenia’s view of seventeenth-century marriage is almost as bleak as the fate awaiting a spinster. In response to a wooer, she says: “nor do I prize my liberty at so low a rate as to exchange it for slavery, or prefer the tyranique yoak of marriage before it; not that I account all wemen slaves, or think all men are Tyrants to their Wives; but if they are not they are at least capable of becoming so when ere they please” (1.7.83 v ). Bridget Manningham resists patriarchal structures and takes a very bleak view of the position of women in seventeenth-century Britain. Arthenia, even more than the royal Oriana and Artabella, has limited choices.

Loreto, Arthenia’s first wooer, is introduced as a young Cavalier who distinguishes himself by holding a bridge and then “when the souldiers under his command wanted Bullets, he instantly caus’d all the mony he had brought with him for his owne perticuler expences, to be cut in pieces” (1.6.73 v ) and then used as bullets. Later, he becomes the Restoration gallant bent on seducing her but conceals his intentions by vowing eternal love. Although he acknowledges that her beauty first attracted him, he claims, “t’was that Vertue that I am perswaded you are absolute Mistress of which made my heart your willing Prisoner” (1.7.83 r ) and then assures her that his intentions are honorable: {26}

Then think not Madam that my respects for you are attended with ought but honour; nor that I have any other design then to lay both my self and Fortune at your Feet, wishing no greater glory, nor satisfaction then to make my selfe yours by Hymens sacred tye. (1.7.83 r )

In spite of these protestations, Loreto proves false.

Until his aunt dies, Loreto is dependent on his mother for support. He woos the aged Madona, whom Manningham describes as a “Golden Bait” (I.7.88 v ), and then marries the wealthy Belissa. After he marries Belissa, Arthenia describes her as “more noble” in birth, more “courtly” in education, more beautiful, and, perhaps most important, possessed of a fortune far exceeding her own (1.7.94 r ). Loreto, however, continues to pursue Arthenia after his marriage, indicating that he has no compunctions about seducing her and sacrificing her virtue to his pleasure.

In the “Continuation” of Arthenia’s adventures in Part 2, she encounters Issodorus, whose passionate avowals of utter devotion prompt her, like Artabella, to commit herself. Issodorus, making a solemn vow to be hers forever, appeals, as did Loreto before him, to “Hymens sacred tye” and insists that she also pledge herself to him (2.Cont.185 v ). Arthenia pledges herself “to be yours and onely yours so long as you are mine” (185 v ). In her role as narrator in the frame, Arthenia candidly admits that this commitment was a mistake (“how willingly do we close our passion blinded eyes; and stop our Eares” [185 v ]), but in the narrative she remains unaware of her own peril. Issodorus, like Loreto, is a predator. Falsely claiming that Arthenia is the first woman he has loved in the seven years since his wife’s death, Issodorus is not contrite when his lies are exposed. He remarks only that love, like war, allows “strategems to get, what by force or treaty” one cannot hope to gain (185 v ). Arthenia, however, remains constant to him even when she attracts the attentions of a wealthier suitor, Silisdes.

Arthenia’s narrative concludes almost immediately after her virtue is compromised. Issodorus arrives limping from a hunting injury. Since he needs to rest before an engagement, Arthenia accompanies him to a room where he can relax and even locks the door. As she begins to leave, he begs her to stay, laying his head on her lap; they both fall asleep. When the door opens exposing Arthenia and Issodorus, Silisdes excuses the compromising situation by assuring the company that Issodorus is her brother. Almost immediately, Arthenia and her real-life brother leave town. Issodorus meets her for a private conference, and she expresses her regret that Issodorus has not given her his picture as he had promised. In the final, seemingly unfinished sentence of the manuscript, Issodorus apologizes and hopes to “make amends for this my first offense which I am” (2.Cont.190 r ). This {27} last sentence breaks off, and the narrative ends without giving any explanation of why Arthenia washed up on the shore of Delphos dressed as a man.[35]

In Arthenia’s history, Manningham weaves the accounts of her wooing by Loreto and then by Issodorus into her descriptions of the historical figures and battles of the Civil War, employing a transparent topicality that may have owed something to literary fashion.[36] The anonymous Theophania, printed in 1655 but written around 1645, for example, also uses Sicily to represent England, Corsica Scotland, Sardinia Ireland, Palermo London, Nicosa Nottingham; the name Clearchus, however, is used for the Duke of Buckingham rather than Charles I.[37] This veiled topicality, according to Stephen Zwicker, satisfied readers who “had an appetite for hidden things.”[38]

A political romance might also aspire to counsel the informed reader. The author of Theophania offers diplomatic advice to the royalist party. Since help from abroad is unlikely, the host Synesis (Robert Sidney, Earl of Leicester) counsels Alexandro (Prince Charles) to advise his father to negotiate a peace with Corastus (Cromwell), and Alexandro pledges to do so.[39] In some romances, the topicality may be included to enhance its seriousness. Sir George Mackenzie’s Aretina: A Serious Romance (1660), for example, inserts a spate of topical allegory distinctly different from the rest of the romance and concludes with the bonfires and bells accompanying the reinstatement of Theopemptus (Charles II).[40] In Sir Percy Herbert’s Cloria and Narcissus (1653 and 1654), later expanded into Princess {29} Cloria (1661), the author addresses an elite audience whom he pointedly elevates above the “vulgar sort” who read his Princess Cloria only for entertainment.[41]

The Civil War is not only the backdrop to Arthenia’s narrative. While astutely recognizing that money and property are beginning to supersede the importance of birth and class in Restoration Britain, Bridget Manningham also understands that the Civil War may change the type of romance that will be written. The frame and the narrative symbolically interact as Arthenia relates the story of the execution of a king. On the day appointed for his execution, Charles I acts with Christlike dignity, even forgiving those who have humiliated him and sought his death. Charles “with a greater Patience than ever Mortall was before endued” (1.6.74 v ) submits to the executioner who severs his head and exposes “it to the view of all such as had the heart to behold so dismall, and afflicting an Object” (74 v ). Arthenia brands the execution a “heinous Crime without example” (74 v ). Queen Ermillia, who is part of the audience listening to Arthenia’s narrative, significantly exclaims:

I am most strangly amaz’d (repli’d the Queen) at what you tell me, that I should scarce take this story for any other then a Romantick Fiction, did you not assure me tis a reall truth. (1.6. 74 v )

Arthenia’s narrative is rooted in fact, and when Queen Ermillia, who is herself a figure in a fictional romance, exclaims that Charles’s execution must be a fiction, we recognize that Manningham has moved from Artabella’s romance to Arthenia’s history; exotic locales have receded in favor of everyday experiences, and a new literary form has begun to emerge.

Editorial Principles of this Edition

Theories of textual editing have identified two central areas of debate, attribution and modernization. Attribution remains controversial especially when dealing with 1) anonymous works; 2) works extant in two or more texts but attributed to different authors; and 3) works, widely understood to be scribal publications, which may have been composed by their authors in different formats or languages, or may have been modified by readers or copyists who actively revise texts during the transmission process. The value of attribution itself has also been questioned. For example, there has recently been a call for recognizing{30} anonymity as a category of authorship.[42] The Modern Language Association awarded a prize to an edition of Sir Walter Ralegh’s poetry in which the editor identifies when and where a poem was attributed to Ralegh but takes no stand on these attributions.[43] Attributions of poems to major authors frequently provoke controversy, and, in some instances, these discussions can be productive.[44]

Rivall Friendship was considered to be anonymous when it was acquired by the Newberry Library from the bookseller, Pickering and Chatto. The case for the authorship of Bridget Manningham is presented above in the Introduction. Additional evidence, of course, might surface and be used to make a case for another author. Rather than dwelling on such uncertainties, this edition makes the best possible case for the attribution of Rivall Friendship to Bridget Manningham.

On the issue of modernization, there is no consensus concerning how to edit early modern texts as witnessed by the tradition of modernizing Shakespeare and printing Edmund Spenser’s works in old spelling editions. It could be argued that Shakespeare’s prominence in the school curriculum has been maintained by the availability of modernized texts, but then we need to keep in mind excesses such as the modernization of Hamlet’s famous soliloquy to “To be or not to be” from “that is the question” to “that is what is the matter.” Few old spelling texts can claim to be printed from an author’s holograph manuscript. As Jean Robertson and Victor Skretkowicz, editors respectively of Sir Philip Sidney’s Old and New Arcadias, have pointed out, if no manuscript in the author’s hand is extant, an old spelling edition merely preserves the “idiosyncrasies of one particular scribe” or, in the case of printed texts, its compositor or compositors.[45] On the other hand, even those who favor modernization recognize that something is lost when we make a sixteenth- or seventeeth-century narrative read like its modern equivalent. Addressing this very point from an historical perspective, Maurice Evans, who modernizes spelling in his edition of Sidney’s Arcadia, observes:{31}

I have made no attempt to modernize the vocabulary since Sidney himself used deliberately archaic language appropriate to the decorum of a Romance and designed to raise the style above the colloquial level in accordance with the best Heroic theory.[46]

No easy answer exists for the editor of an early modern text.

Succinctly stated, the editorial dilemma facing an editor of Rivall Friendship is whether to transcribe verbatim, regularize, or modernize this two part seventeenth-century romance. In A Continuation of Sir Philip Sidney’s “Arcadia” by Anna Weamys, Patrick Colborn Cullen reprints the 1651 printed edition and also supplies a modernized text.[47] The length of Rivall Friendship makes a printed transcription accompanied by a modernization impractical.

Transcription

My editorial decision to transcribe Rivall Friendship with minimal regularization and modernization was influenced chiefly by the consideration that this manuscript appears to be unique and so an accurate transcription is of the first importance. Second, even without modernizing spelling and syntax, the language of Rivall Friendship is accessible to most modern readers, particularly to those students and scholars accustomed to working with seventeenth-century texts.[48] Even the general reader of Malory’s Knights of King Arthur or Chaucer will not find the syntax or vocabulary impenetrable. In the interest of assisting that general reader, Appendix 2 identifies historical figures and places, and Appendix 3 lists the names of characters.

Rivall Friendship survives in one manuscript copy, and this manuscript preserves a readable text; therefore, this edition attempts to reproduce this manuscript as faithfully as possible. The single intervention in the direction of modernization has been to introduce paragraphing to distinguish speakers and to indicate major breaks in the narrative such as changes of location or time of day. In instances when spelling may render meaning unclear, a modern orthography is suggested in brackets, for example “mene” [mien]. These editorial decisions{32} are motivated by the desire to “intervene no more than necessary for the sake of reasonable clarity.”[49]

Two features of Rivall Friendship may be useful to point out: 1) handwriting: there are at least three identifiable hands (Figures 1–3). In contrast to the other two hands that cross out a word to be deleted, the correcting hand underlines a word for deletion and then inserts a correction. As noted previously, the correcting hand initially makes substantive changes but later concentrates on correcting spelling–always in the direction of modernity. These emendations are pointed out in textual footnotes. 2) vocabulary: the words “resent” (v) and “resentment” (n), deriving from resentir in French, are used to refer to sentiments or intense feelings as well as the feeling of indignation or having a grudge. It is useful to point out that the word “resentment” is corrected by the correcting hand to “sentiments” (1.1.14 r ). {33}

Conventions of this Transcription

- Obvious errors such as missing parentheses to indicate a speaker or missing close parentheses have been silently corrected, e.g., “my name (repli’d he).”

- Names of characters have been regularized and italicized throughout except in instances in which the manuscript indicates that only the name is to be italicized, not the possessive marker, “s”, e.g. “Artabellas” in which Artabella is italicized but “s” is not.

- If there are possibilities of two readings (e.g., “Silvan sports” or “Silvah sports”), then the reading is selected which is closer to normal usage in modern English.

- No attempt has been made to correct either to/too or then /than when comparisons are indicated, e.g., “by the advantage of her dress, which was much more becoming then the Persian habit”; or “certain it is, he thought her more faire and Excellent then the Sea-born Goddess.”

- The periphrastic possessive, “the Prince his quarrel,” for “the Prince’s quarrel,” has been retained throughout.

- Regularization of spelling, capitalization, and abbreviations:

- i/j, u/v. have been normalized throughout.

- Capitalization has been modernized for double consonants, e.g., “flying upon the wwinges of ffeare” becomes “Wings of Feare.”

- Slash marks showing word or line divisions have been removed, as well as catch words indicating the first word of the following page.

- Abbreviations expanded without textual notes:

- Matie = Majestie

- Maties= Majesties

- Mrs = Mistress

- Sr = Sir

- Wch = which

- Wt = with

- Ye = the

- Yr = your

- Yt = that

- Your = your

- the[n] above the line has been silently expanded

- The tilde [~] or macron [-] to indicate m or n has silently been completed

- Anthony G. Petti, English Literary Hands from Chaucer to Dryden (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1977). ↵

- {3} References to the manuscript will specify Part 1 or 2, Book number, and foliation, e.g., Part 2. Book 3. 134 v will be listed as 2.3.134 v . In Part 2, Arthenia’s experiences are not divided into books but designated as “The Continuation of Arthenia’s Story” (Cont.). Jill Gage, Custodian of the John M. Wing Foundation on the History of Printing at the Newberry Library, graciously oversaw this foliation. ↵

- For modern editions, see The First Part of the Countess of Montgomery’s Urania, ed. Josephine A. Roberts (Binghamton, New York: MRTS at Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 1995) and The Second Part of The Countess of Montgomery’s Urania, ed. Josephine A. Roberts, completed by Suzanne Gossett and Janel Mueller (Tempe, AZ: ACMRS Press at the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 1999). ↵

- For a description of this manuscript, see John D. Hurrell, “An Unpublished Novel of the Seventeenth Century: George Hitchcock’s ‘The Lady Alice Oldfeild Her Kallicia and Philaedus,’” The Newberry Library Bulletin, 6, No. 10 (May 1979), 345–52. Hurrell identifies the author as George Hitchcock, son of John Hitchcock, Esq., a barrister at Grey’s Inn. ↵

- Anon., Theophania: Or, Several Modern Histories Represented by Way of Romance, and Politicly Discours’d Upon, Publications of the Barnabe Riche Society 10, ed. Renee Pigeon (Ottawa, Canada: Dovehouse Editions, 1999). For the seemingly unsubstantiated attribution to Sir William Sales, see 12. ↵

- This watermark resembles the horn on a shield identified as No. 2670, part of the group consisting of 2668–71 and dated c. 1665–80, as well as No. 2779 (dated 1650) in Edward Heawood, Watermarks, Mainly of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Monumenta Chartae Papyraceae Historiam Illustrantia (Hilversum, Holland: Paper Publications Society, 1950), PL 340 and PL 357. ↵

- The watermark, appearing only in the endpapers, seems to reproduce exactly the coat of arms, No.450 (dated 1760) in Heawood, Watermarks, Mainly of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, PL 76. ↵

- For Manningham’s will, see The National Archives: PRO, PROB 11/587. Sig. 176. ↵

- For the transmission of pictures and embroidered caskets through the female line, particularly in royalist households, see Mihoko Suzuki, Subordinate Subjects: Gender, the Political Nation, and Literary Form in England, 1588–1688 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), 170–73. ↵

- {8}The Ellis Correspondence: Letters written During the Years 1686, 1687, 1688, and Addressed to John Ellis, Esq. Comprising many Particulars of the Revolution, ed. Hon. Agar Ellis, 2 vols. (London: Henry Colburn, New Burlington Streets, 1829), I: xii-xxiii. The original letters are preserved in the Birch Collection, British Library. For a brief history of the Ellis family, who may have owned the manuscript in the eighteenth century, see Appendix 1. ↵

- In the note signed by M. A. L., Bishop Thomas Manningham’s name is followed by the date 1696, but this date, unless it indicates flourished, does not appear significant in his life. ↵

- Anthony Wood, Athenae Oxonienses, An Exact History of All the Writers and Bishops Who Have Had their Education in the University of Oxford, new edition with additions by Philip Bliss, 4 vols. (London: Thomas Davison, 1820), 4:5555 ↵

- John Nichols, Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century, Comprizing Biographical Memoirs of William Bowyer, Printer, F. S. A. and Many of his Learned Friends, 6 vols. (London: Nichols, Son, and Bentley, 1812), 1: 208. ↵

- Donald Gray, Thomas Manningham,” ODNB, online 3 Jan 2008. ↵

- Thomas Manningham, A Solemn Humiliation for the Murder of Charles I. With some Remarks on those Popular Mistakes, Concerning Popery, Zeal, and the Extent of Subjection, which had a fatal Influence in our Civil Wars. (London: Printed by F. Collins for W. Crooke, 1686), D2 r , p. 19. [D.M. 509]. From the Huntington Library copy RB 223650. ↵

- Sermon No. 30 in a collection of thirty-three sermons. See “The Nature and Effects of Superstition.” In a Sermon. Preached before the Honourable House of Commons, on Saturday, the Fifth November 1692. By Thomas Manningham, D.D. and Chaplain in Ordinary to their Majesties. (London: Thomas Braddyll and Robert Everingham, 1692), C1 v, p. 10. [E-PV]. From the Huntington Library copy RB 439690–722. ↵

- Sermon No. 5 in Six Sermons preached on the Occasions Following: . . . A Sermon on Shrove-Tuesday, at the Feast of the Natives of Hampshire. (London: Printed by F. Collins, for W. Crooke, 1686), D1 r , p. 17 and D4 v , p. 24. [D.M. 508]. From the Huntington Library copy RB 316383. ↵

- Nichols, Literary Anecdotes, 1:208. ↵

- Notes and Queries: A Medium of Intercommunication for Literary Men, General Readers, etc., 8th series, vol. 5, January-June 1894 (London: Office Bream’s Bldgs., Chancery Lane by John C. Francis, 1894), 411. ↵

- Ibid., see also PCC, 261, Bettesworth. ↵

- Publications of the Thoresby Society, For the year 1908: A History of the Parish of Barivich in Elmet, York, ed. F. S. Colman, vol. 17 (Leeds: Knight and Forster, 1908), 257–58. The marriage is not recorded in The Parish Registers of St. Michael, Cornhill, London Containing Marriages, Baptisms, and Burials From 1546 to 1754, ed. Joseph Lemuel Chester (London: 1882), but it is likely that Mary Rawlinson would have been married by her father, Rev. Dr. Robert Rawlinson of Charlwood, Surrey. ↵

- Publications of the Thoresby Society, 17: 258. ↵

- See The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia [The Old Arcadia], ed. Jean Robertson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973), v–vii and xlii–lxvi. See also H. R. Woudhuysen, Sir Philip Sidney and the Circulation of Manuscripts, 1558–1640 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996). ↵

- The Poems of Robert Sidney, ed. P. J. Croft (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984). ↵

- For Lady Mary’s biography, see Margaret P. Hannay, Mary Sidney, Lady Wroth (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010). ↵

- Diary of John Manningham, of the Middle Temple, and of Bradbourne, Kent, barrister-at-law, Camden Society, os. 99, ed. John Bruce (Westminster: J. B. Nichols and Sons, 1868). Bruce seems to have been responsible for the attribution of the manuscript to John Manningham of Bradbourne House, Kent. For a modern edition, see The Diary of John Manningham of the Middle Temple, 1602–1603, ed. Robert Parker Sorlien (Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 1976), 265. ↵

- For this information, see the genealogical appendices to The Diary of John Manningham, ed. Sorlien. ↵

- For Thomas Twisden, see J. R. Twisden, The Family of Twysden and Twisden: Their History and Archives (London: John Murray, 1939). ↵

- The terms, “romance” and “novel,” refer to prose fiction in general. On early modern usage, see Christine S. Lee, “The Meanings of Romance: Rethinking Early Modern Fiction,” Modern Philology (2014), 287–311. See also James Grantham Turner, “Romance and the Novel in Restoration England,” Review of English Studies, 63.258 (2011): 58–85. For more general studies, see Helen Hackett, Women and Romance Fiction in the English Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000) and the Introduction (xviii-xix) to Prose Fiction in English from the Origins of Print to 1750, ed. Thomas Keymer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). ↵

- Feminism, like education of the lower classes, is not a progressive history. After the English Civil War, reformers hesitated to educate the lower classes because they feared that the overproduction of intellectuals might breed social unrest. Lawrence Stone concludes that in quantitative terms, it was not until after World War I that English higher education was as egalitarian as it was in the 1630s. See Stone, “The Educational Revolution in England, 1560–1640,” Past and Present 28 (1964), 41–80, esp. 69. ↵

- In a passage suggesting that Manningham may have known Plutarch as well as Shakespeare, we are told that Phasellus was descended from Marc Antony, “one who though he never bare the burden of a Crown” had “the satisfaction to behold many puissant Kings his Vassalls prostrate their Crowns and Scepters at his Feet” (1.2.28 v ). Fortune was kinder to “Augustus with whom he disputed the Empier of the World” (28 v ) or he [Marc Antony] would have “questionless worn that Empieriall Diadem which his Predescessor Julius Caesar onely fancied, never really put on; being by treachery cut off ere he could bring his design to maturity” (28 v ). ↵

- Herodotus, Histories, Books V–VII: The Persian Wars, trans. A.D. Godley, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1922), 7, 11. ↵

- Peter Heylyn, Cosmographie (London, 1652), 175. ↵

- Steve Mentz, Romance for Sale in Early Modern England (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), 33, 77–83, 105–122, 152–161. For a translator of French heroic romances who may have influenced Manningham, see Joseph E. Tucker, “John Davies of Kidwelly (1627? -1693), Translator from the French: With an Annotated Bibliography of his Translations,” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 44, No. 2 (1950), 119–52. For example, Davies, like Manningham, uses the verb “resent” and the noun “resentment” to signify deep feelings as well as a grudge against someone. ↵

- See Figure 8. I am indebted to William Gentrup for suggesting that the manuscript may not have been finished because the manuscript concludes at the very bottom of the folio page, rather than mid-page (Figure 8). The final pages may have been lost. ↵

- Pertinent discussions include Paul Salzman, English Prose Fiction, 1558–1770, 148–201; Paul Salzman, “Royalist Epic and Romance,” The Cambridge Companion to Writing of the English Revolution, ed. N. H. Keeble (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 215–30; Nigel Smith, Literature and Revolution in England, 1640–1660 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), 233–49, esp. 234. ↵

- Theophania (1655), ed. Pigeon, 37, 287. ↵

- Steven N. Zwicker, “Royalist Romance?” Prose Fiction in English from the Origins of Print to 1750, 243–259, esp. 252; vol. 1 of the Oxford History of the Novel in English, ed. Thomas Keymer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). See also Aemilia Zurcher, Seventeenth-Century English Romance: Allegory, Ethics, and Politics (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). For the suggestion that romance became a genre from which much could be learned, see Lois Potter, Secret Rites and Secret Writing: Royalist Literature, 1641–1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 73–90, esp. 75. ↵

- Theophania (1655), ed. Pigeon. Cenodoxius (2nd Earl of Essex), who commands the Parliamentarian army, claims that he had no intent to uncrown the king. ↵

- George Mackenzie, Aretina: A Serious Romance (London: Robert Broun, 1660), Book 3. ↵

- Preface to Sir Percy Herbert, Princess Cloria (London: Ralph Wood, 1661). For commentary on the political romance, see Paul Salzman, “The Princess Cloria and the Political Romance in the 1650s: Royalist Propaganda in the Interregnum,” Southern Review (1981): 236–46. ↵

- See, for example, Marcy L. North, The Anonymous Renaissance: Cultures of Discretion in Tudor-Stuart England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003); see also North’s “Amateur Compilers, Scribal Labour, and the Contents of Early Modern Poetic Miscellanies,” English Manuscript Studies 16 (2011): 82–111. ↵

- The Poems of Sir Walter Ralegh: A Historical Edition, ed. Michael Rudick, Renaissance English Texts Society, 23 (Tempe, AZ: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1999). ↵

- Don W. Foster, Elegy by W. S.: A Study in Attribution (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 1989). See also Foster’s argument that each author has a literary fingerprint in Author Unknown: On the Trail of Anonymous (New York: Henry Holt, 2000). ↵

- The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia [The Old Arcadia], ed. Robertson, lxix and The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia [The New Arcadia], ed. Victor Skretkowicz (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), lxxx. ↵

- Sir Philip Sidney, The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia, Penguin Classics, ed. Maurice Evans, (London: Penguin, 1977), 47. ↵

- A Continuation of Sir Philip Sidney’s “Arcadia” by Anna Weamys, Women Writers in English 1350–1850, ed. Patrick Colborn Cullen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994). ↵

- Modernization also opens the door to issues such as whether to prefer British to American spelling (favour to favor; rigour to rigor; colour to color; humour to humor). Rivall Friendship sometimes uses spelling now associated with American rather than British spelling. ↵

- Cullen, ed. Weamys, lxvii. ↵