Race, Empire, and Cartography

Ricardo Padrón and Risa Puleo

[Print edition page number: 107]

We often think of maps as objective representations of territory but, in actuality, they tend to embody a particular point of view, one that is embedded in the culture and ideology of the mapmaker, not to mention the particular purposes for which the map was made. This essay explores the relationship between maps and race in two very different cartographic projects produced in two very different contexts for very different reasons. The first, a set of maps by the French mapmaker Nicolas de Fer (1646–1720) represents one of many attempts by European intellectuals to make the world and its people visible to their fellow Europeans in ways that were supposed to be objective and scientific but were in fact saturated with the ideology of Eurocentrism that sustained Western colonialism. The second, a map made by an unknown Native inhabitant of colonial Mexico and known as the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map (1569),[111] represents one of the many maps produced by Indigenous Americans in their effort to defend a variety of interests from the onslaught of Spanish colonialism. Each of these projects has its own voice, its own politics, its own complex point of view. The de Fer maps allow us to appreciate how Western ideas about race developed in tandem with ideas about global geography; the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map allows us to appreciate how maps became tools in the effort to resist racialized notions of property ownership.

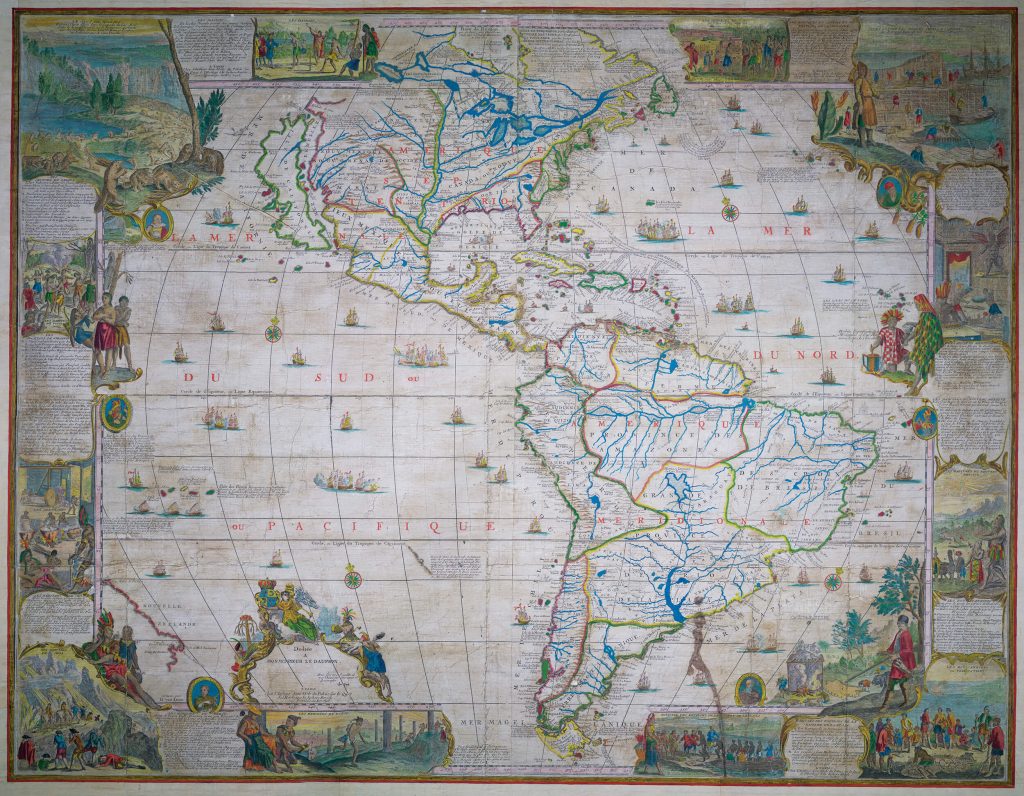

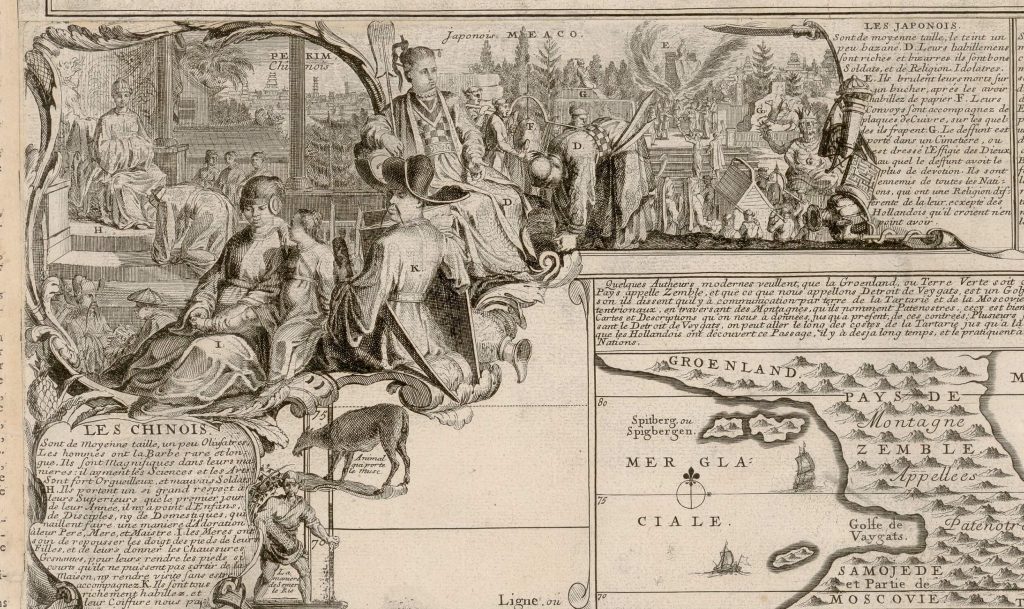

The de Fer maps, made in Paris toward the end of the 1690s, depict the four parts of the world, Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, in monumental style[108] (Figure 4.1).[1] These were luxury products produced by a preeminent mapmaker with close ties to the royal family. Each was printed on eight sheets of paper from custom-made copper plates. The pieces were then assembled into a single image roughly 160cm wide and 110cm tall, one so massive that it could only be taken in when mounted on a wall. The maps were not only enormous, but also encyclopedic. They include lengthy verbal descriptions of the continents, as well as numerous captioned illustrations that depict the various human communities that inhabited each continent. We know little about the sources that de Fer used to construct and illustrate his maps, but we can tell that he meant them to be authoritative. In the pages that follow, we read them in the context of the history of European approaches to human difference on a global scale. They capture a moment in the history of European racial thinking when notions of Eurocentrism that were so fundamental to the colonial enterprise of the West had been fully consolidated, yet they also dramatize the ways the human migrations at the heart of that enterprise cried out for a notion of biological race that could consolidate the ongoing construction of white supremacy.

Nicolas de Fer, “L’Amérique, Divisée Selon l’etendue Ses Principales Parties,” 1698, Newberry Library, Novacco 8F 02 01

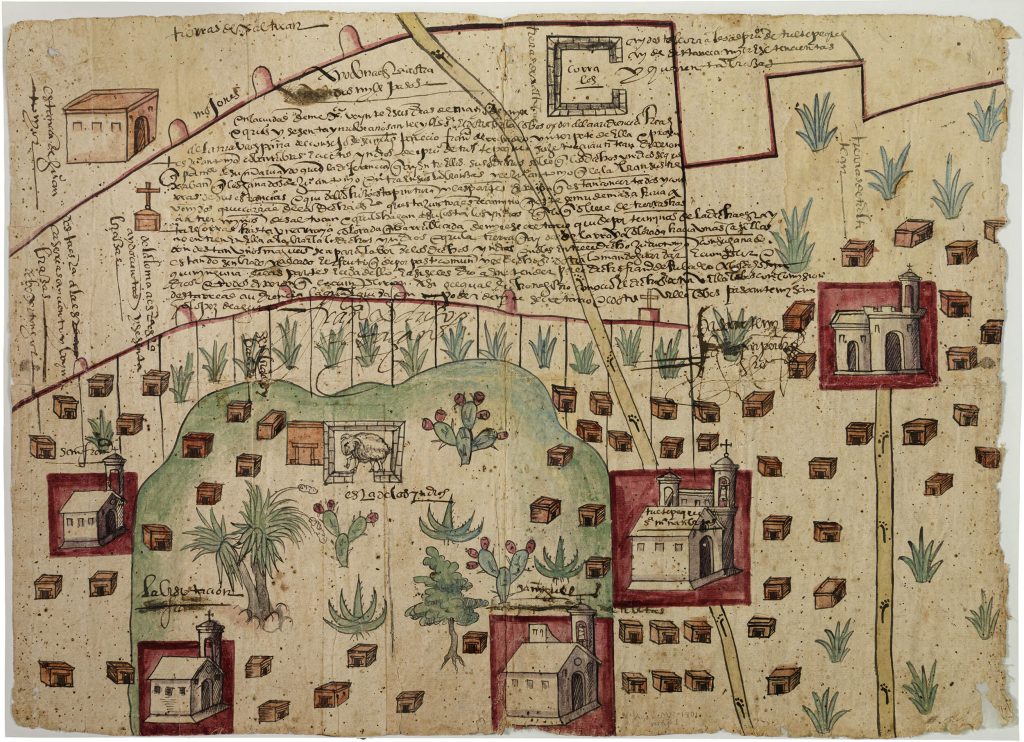

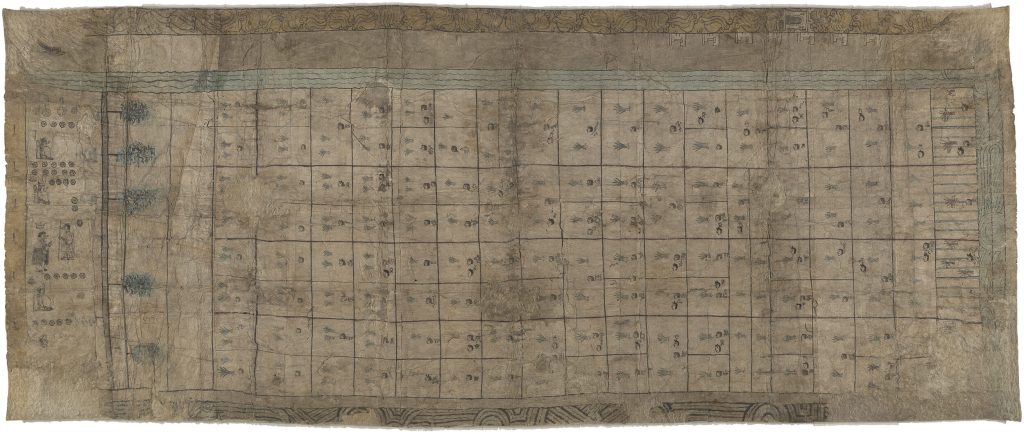

The Farmers vs. Covarrubias map, conversely, depicts the local setting of a community of Indigenous people in colonial Mexico. It was painted on paper made from the bark of a mulberry or fig tree, using paper-making traditions practiced in the Americas long before the arrival of the Spanish (Figure 4.2). The pigments used to color the terrain[110] derived from botanicals and minerals found in the landscape. The Indigenous mapmaker who made this map did so with subtle knowledge about the land, not only its topography, but also details about where to find the materials to make the map itself that can only be attained through studied interactions with its flora and fauna across generations. Despite this ancestral relationship to the land, the mapmaker who made this map did so to defend his community’s claim to it and right to be on it. The Farmers vs Covarrubias gets its name from the 1569 court case in which the two named parties appealed to a colonial court to settle a dispute about the boundaries of property. Made just under fifty years after the Spanish military conquest of the Americas, the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map shows us how race was mediated by property lines in the earliest moments of Spanish occupation. Maps produced to support legal claims to territory in court cases demonstrate how Spaniards attempted to control the Indigenous population, los naturales, through a system of bureaucracy that was far from natural. As an example of this type of map, Farmers vs. Covarrubias shows how an Indigenous mapmaker, who represented the people of Tultepec, made claim to space and navigated a bureaucratic web using a system of picture-writing that was illegible to the Spanish court system.

Though made many decades after the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map, the de Fer map is discussed first because of the global nature of the mapping project. We then turn to the more localized issues raised by the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map.

The World Viewed from Paris

by Ricardo Padrón

The division of the world into continents is largely arbitrary and has a lengthy history. The Ancient Greeks were the first to divide the world this way, but they disagreed about whether the world had two or three parts. Some of them even believed that the whole system was ill-conceived and best abandoned.[2] Medieval intellectuals settled on three parts, but the number rose to four when their early modern successors designated the newly-discovered lands in the Atlantic a “fourth part of the world” called “America.”[3] Today, English-speakers usually learn that there are seven continents, while Spanish-speakers learn that there are six, thanks to the tendency in Latin America to count the Western hemisphere as a single landmass. Just as there have been disagreements over the number of the world’s parts, so there have been disagreements over their boundaries. The same medieval intellectuals who set the number at three also determined that the parts of the world were separated by the Mediterranean Sea, the Nile River, and the Don River. As Europeans began to map Russia’s rivers with accuracy, however, it became clear that the Don River did not extend far enough North to serve as a boundary between Europe and Asia. Eventually, a Swedish army officer suggested that the Ural Mountains would work better than any river.

This example illustrates a key idea: the way that we chop the world up into continents goes hand in hand with value judgments about people who live in certain places, and how they size up in comparison with others elsewhere. The decision to identify the Ural Mountains as the true border was controversial, but it was well received among Russian intellectuals who supported Tsar Peter the Great’s efforts to Westernize their country, because it identified the Russian heartland as “European” rather than “Asian” or “Oriental.”[4] Conveniently, it also consigned Siberia to Asia, converting it into a space ripe for colonization.[5] The question nevertheless remains unsettled. Martin Lewis and Karen Wïgen have gone so far as to argue that Europe should be deprived of continental status, because it is actually no larger or any more diverse than the various subcontinents that comprise Asia. The elevation of Europe to continental status on a par with Asia, in fact, constitutes one of the central gestures of Eurocentrism.[6] The de Fer maps illustrate this perfectly, but they also help us understand why elevating the status of Europe and its people did not in itself suffice as a way of underwriting the project of European colonialism. The fact was that in the early modern world, people moved around, and this made the notion of biological race not only convenient but necessary to sustaining the project of European colonialism on a global level.

From Climates to Continents

In order to understand this, it helps to go back to a time when the continents mattered much less. Before the early modern period (1300–1700), the architecture of the continents did not figure as prominently in global geography as another system, the theory of climate.[7] According to the Ancient Greeks, climate had a[113] powerful influence on human character, and climate was a function of latitude.[8] Hot, humid places toward the south of the known world, like the Nile Valley or far-off India, produced people who were clever but timid to the point of being servile, with dark skin and coarse hair. When they did not live in savage bands, they cowered under the rule of tyrants. Cold northern places like Germany, by contrast, produced people who were brutish but brave, with fair complexions. Places in the temperate middle, like Greece, combined the best of both extremes, producing people with both the bravery of northern types and the cleverness of southern ones. Only they were truly capable of living lives that counted as rational and civilized, as the Greeks understood those terms. What mattered most in mapping the global distribution of different human difference, therefore, was not the continents but the latitudinal climatic bands or zones into which the Earth was divided.

Such differences — white versus Black, “civilized” versus “barbarian,” “masters” versus “slaves” — were not a function of biological inheritance but of environmental influence. In this way, climate theory differed from modern racism, but it nevertheless played the same role, that of articulating and managing human difference in ways that distributed power and privilege asymmetrically among different human groups, favoring the group that invented the theory.[9] This was especially true as the Portuguese and the Spanish began to expand into the Atlantic world, and discovered that the ancients had been wrong about climate in one important respect. Near the equator, where the heat was supposed to become so intense as to make life impossible, according to Aristotle, Iberian explorers encountered lush tropical locales, rich in spices and precious metals, and inhabited by people they deemed uncivilized. All of a sudden, the tropical south loomed large and seemed readily available for exploitation. It was not long before apologists of Spain’s empire like Juan López de Palacios Rubios (1450–1524) and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda (1494–1573) began to argue that the Native inhabitants of what they called “the Indies” were the “natural slaves” that Aristotle described in his Politics, a people who desperately needed what they considered to be the civilizing influence of Spain.[10]

The very fact, however, that they had to invoke the theory of natural slavery in order to justify colonialism suggests that climate theory alone was inadequate. In fact, it suffered a key limitation, and by the last quarter of the sixteenth century, intellectuals involved in managing Spain’s empire were well aware of it. According to climate theory, Europeans who moved to the tropics would eventually come to resemble the Native inhabitants in body and mind. The change might take generations, but it was inevitable. When a Spanish cosmographer admitted as much in a description of the Indies he hoped to have published, an official censor struck the passage out of the text.[11] He must have realized how very inconvenient it was to admit that Europeans could degenerate in a tropical environment, losing the qualities that made them “natural masters.”

The architecture of the continents began to emerge as a solution to the problem. According to Francisco Bethencourt, it was during the early modern period that Europeans began to assemble stereotypes about the peoples of the world following the logic of the[114] continents rather than the climatic zones.[12] These stereotypes were crystallized in a famous image that appeared on the title page of the first modern atlas, Abraham Ortelius’s Theatrum orbis terrarum (1570) (Cat. No. 26). It depicts the world as a group of female figures who embody the parts of the world: Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, and has been analyzed time and again.[13] The attributes of the figures and their spatial arrangement on the page suggests a clear cultural and geographical hierarchy. Europe sits at the top, fully dressed and wearing a crown, holding symbols of empire, and surrounded by emblems of culture and knowledge. Asia and Africa stand opposite each other on the next tier down, the one wearing less than the other, both of them holding exotic commodities. America stretches out the bottom, practically nude, holding primitive weapons and brandishing the remains of a cannibalistic feast.

Europe can occupy the top spot precisely because Ortelius has chosen the continents rather than the climatic zones as his basic geographical framework. That choice probably made little difference in the handling of America and Africa, because notions of tropicality dominated European thinking about those parts of the world; these notions made it possible to ignore signs of American or African sophistication, like the cities of the Aztecs and Inca or the glittering wealth of Mali, and depict all Native Americans and Black Africans as “uncivilized” people. Where the choice really mattered was in the treatment of Europe and Asia. Climate theory divided Asia into a temperate north and a tropical south. The north was home to the Chinese and Japanese, who were thought to be white-skinned near-peers of civilized Europeans. The south was home to the dark-skinned, supposedly less civilized people of South and Southeast Asia. The architecture of the continents, however, required Ortelius to depict a single, unified Asia, and therefore allowed him to make a choice between the two. Rather than depict Asia as a learned mandarin, for example, he depicted it as an eroticized woman holding a censer of myrrh, favoring the exotic sensuality associated with the south while erasing the civility of the north. This allowed Europe to sit at the top of the hierarchy all by herself, white, knowledgeable, and in charge. The problems posed by climate and the threat of tropical degeneracy were simply set aside.

Those problems, however, did not go away. The notion that the tropics exercised a degenerative influence on European bodies and minds continued to vex Westerners, creating fertile circumstances for the development of new theories of difference. The raw materials were already there in notions that the blood of aristocratic elites or white Christians was “pure” of the taint of disbelief that was carried in the blood of Jews and Muslims. These ideas, which made identity a function of biological inheritance rather than environmental influence, migrated to the colonies, where they were adapted to impose order on societies where people of all kinds were mixing in ways that the authorities found alarming. The “impure blood” of Jews became that of the Indigenous Americans.[14] The “pure” blood of French aristocrats became that of all French people.[15] The blood “purity” of Spanish Old Christians became that of the ruling elites of Spanish America.[16] And so forth. Colonial developments of this[115] kind became the background against which metropolitan intellectuals began to articulate modern theories of biological race, albeit often without acknowledging the colonial precedent.

Some of these theories involved new ways of mapping the world. The French physician François Bernier (1620–1688), for example, proposed “A New Division of the Earth” (1684) according to different “races” organized on the basis of physical appearance according to which the inhabitants of Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, Persia, India, and Thailand constituted a single race, converting these lands into a single region.[17] In general, however, new theories of race mapped their hereditary human groups onto the established continental system, even while recognizing that the fit between races and landmasses was not always perfect. Black Africans came to be imagined as descendants of Noah’s son Ham, who had been cursed to a life of servitude by his father.[18] The Chinese and Japanese ceased to be white and became “yellow.”[19] The effects of the environment were shifted to the distant past, when each race became what it was and would forever be, in the relative isolation of its own continental setting. As Carl Ritter (1779–1859), one of the most important geographers of the nineteenth century put it, “Each continent is like itself alone . . . each one was so planned and formed as to have its own special function in the progress of human culture.” One of these functions was to produce a major racial group. Europe produced the “white” race, Africa the “Black” race, Asia the “yellow,” and America the “red.”[20] Eventually, the Native inhabitants of the Pacific were identified as another major group, producing the popular nineteenth-century notion that there existed “five races of man.” In this new dispensation, white people could still degenerate, but not by moving to tropical climates. The French writer Arthur Gobineau (1816–1882) flatly rejected that the environment could profoundly affect human beings within the short span of historical time.[21] The degeneration of the white race was not the result of life in a tropical climate, but of intermarriage with dark-skinned, “inferior” people.[22] This was a truly convenient racial logic for a globalized world, in which populations migrated, freely or not, in which certain groups ruled over others and believed themselves entitled to do so, and wanted very much to keep hold of their power.

The de Fer Maps

The de Fer maps were made in the midst of all these changes. By the 1690s, Bernier had already published his precocious attempt to divide humanity into racial groups. France was well established as a colonial power, with possessions in the Caribbean, North America, and South Asia. In 1685, the French government had enacted the first of its Codes Noirs, or “Black Codes,” laws governing the treatment of enslaved populations that were the first to identify subjects of the crown on the basis of skin color. In the meantime, the government was making it possible for enslavers to bring their human property back to the metropolis, upending centuries of tradition that prohibited slavery on the soil of France. Nevertheless, a full-blown theory of biological racism had not yet emerged, much less come to dominate racial thinking. The word nègre [Black] enjoyed considerable ambiguity when applied to human beings. It could be used to refer to enslaved people, people of African origin, or dark-skinned people from places other than Africa, such as India.[23] This final ambiguity suggests that the French continued to[116] think about human difference in terms of climate theory, conflating the dark-skinned peoples of the tropics into a single category, no matter what their continental origins.

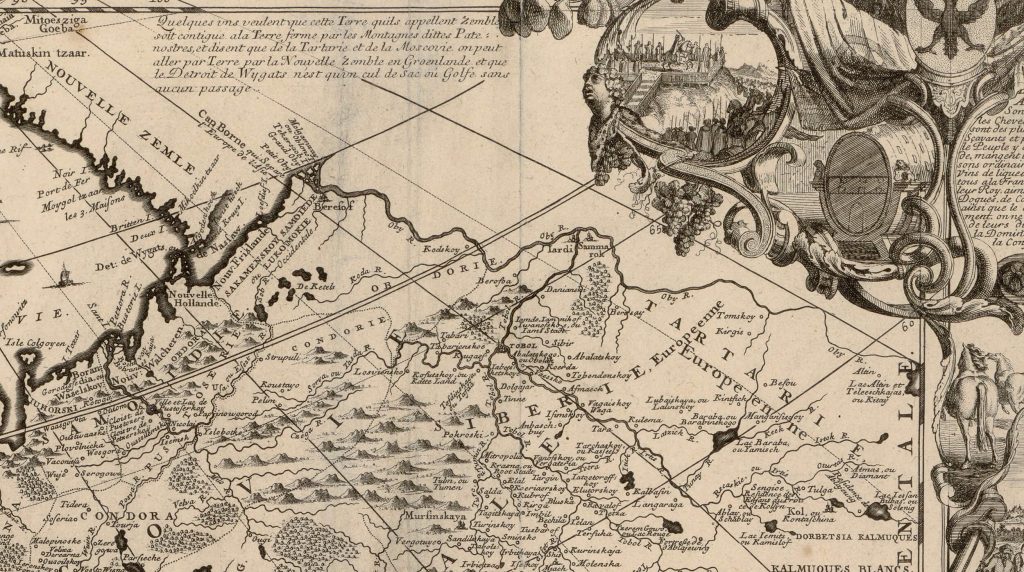

De Fer’s maps help the reader abandon the theory of climate for the architecture of the continents. Once again, the arbitrariness of the system is best grasped by observing the treatment of the boundary between Europe and Asia. The maps identify the Don and Oby Rivers as the boundary between the two continents, but one struggles to see why these rivers and not others should serve as the crucial dividing line (Figure 4.3). We come to realize that it is not the rivers at all, but the material separation of the two continents onto two images of similar size, each using a different cartographic scale. The effect is to zoom in on Europe and zoom out on Asia, converting them into separate but equal landmasses, each of them appearing on a large map, rich in detail, that demands to be taken in on its own. It becomes difficult to see similarities and differences along lines of latitude that traverse the continents themselves, and much easier to make those comparisons continent by continent. The reader is thus trained to treat the continents, not the climates, as the fundamental categories of physical and human geography.

Detail from Nicolas de Fer, “L’Europe Divisée Selon l’étendue de Ses Principales Parties,” Paris, 1696. Bibliothéque Nationale de France. The mapmaker leaves the “Asian” land beyond the Orby River blank, but one fails to see why this river and not some other should serve as the intercontinental boundary. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53089033c.

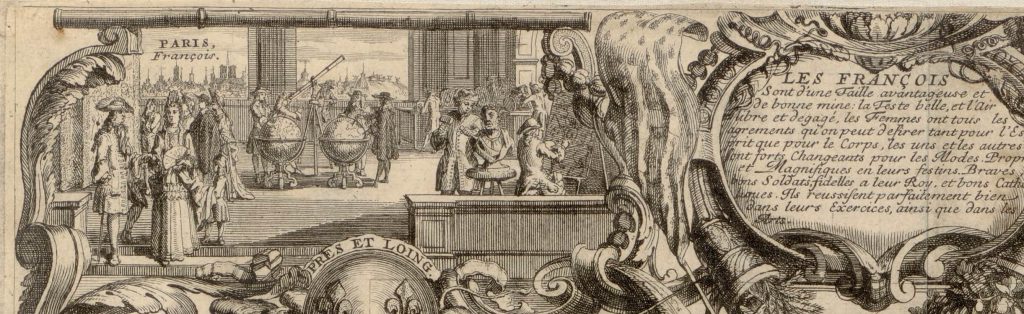

The French and the Chinese, who should exhibit similar levels of civility by virtue of their shared location in the northern temperate zone, come out looking quite different from each other. In the vignette depicting the French, one man sculpts while another paints, a fashionable couple chats, while other groups assemble around a large pair of globes or peer through a telescope (Figure 4.4). The other European vignettes feature urban life, martial prowess, technical inventiveness, and commercial success, while making room for the “oriental” sumptuousness of Istanbul and the “barbarity” of Lapland, but only Paris glows as a center of art and learning. De Fer’s human geography is not only Eurocentric: it is Francocentric. It is from Paris that the world is known and represented. Not only does this vignette say so, but so do all the elaborate title cartouches proclaiming that Paris is the place where the maps were made. The vignette depicting the Chinese, meanwhile, downplays their civility. It depicts an orderly, urbanized world with a rich material culture, and bears a caption acknowledging China’s love for the arts and sciences, but the image of two men discussing a piece of writing is lost in the middle ground, while the text itself draws the reader’s attention to the sumptuous dress of the two figures in the foreground and to the exotic practice[117] of foot binding (Figure 4.5). The Japanese fare even worse, appearing primarily as “idolators” and ferocious warriors. Everywhere else on the map of Asia we find images of excess, luxury, and exoticism typical of modern Orientalism. The map of Africa, meanwhile, features people who are clearly black-skinned, who are often engaged in activities that would be deemed “primitive” by the Parisian reader and are frequently described with exceedingly negative language.

Detail from Nicolas de Fer, “L’Europe Où Tous Les Points Principaux.” Paris, 1695. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The French capital is portrayed as the global headquarters of art and science. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530530140.

Detail from Nicolas de Fer, “L’Asie Divisée Selon l’étendue de Ses Principales Parties . . .,” Paris, 1696. Bibliothéque Nationale de France. The vignette about the Chinese downplays Chinese literacy, and shines the spotlight on Asian exoticisim. The vignette about the Japanese emphasizes violence and idolatry. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53089033c

In treating Europe, Asia, and Africa in this way, de Fer draws on a representational tradition established roughly one-hundred years earlier, that of the so-called cartes à figures (Cat. No. 24). On these maps, the inhabitants of the region depicted — whether it was a locality, a kingdom, a continent, or the world as a whole — appeared along the image margins as stylized, costumed individuals or couples.[24] De Fer replaces the stiff figures of the carte à figure with action scenes: animal hunts, musical performances, coronations, mining, divine worship, star gazing, cannibalism, and a myriad of other things. The identity of the people depicted is not just a matter of what they wear, but what they typically or most characteristically do. In each case, however, the people in question seem to be the Native inhabitants of that continent. They exhibit diversity while simultaneously falling into the overall patterns typical of Europeans, Asians, or Africans.

It is here that America begins to look like the odd map out (Figure 4.1). The map is famous for its depiction of beavers busily building a dam, but here I will focus on its treatment of human populations. Like the others, the map of America portrays Native inhabitants of the continent, group by group. It portrays the civilizations of the Mexica and the Inca as having occurred in the past, and tinges them with strong[118] hints of “savagery” and “idolatry.” Other Indigenous groups are rendered as either peaceful or warlike but seem to be universally “primitive.” In this way, de Fer’s map of America participates in the proto-racialization of the Indigenous Americans. Nevertheless, it also forces Native Americans to share the space of representation with Europeans and Africans. European cod fishermen, buccaneers, and Spanish conquistadors get their own vignettes. Whites sell enslaved Africans to the Indigenous inhabitants of Río de la Plata, while in Brazil, enslaved Black people engage in the grueling work of sugar production. In this way, de Fer’s America looks like the home of a “race,” just like the other maps, but it also renders visible the key phenomenon that made a notion of biological race so essential to the project of European colonialism: the migration, voluntary or not, of Europeans and Africans to the New World. De Fer’s map dramatizes the presence of white and Black communities in places that are not Native to them, inviting the reader to see how they remain the same no matter where they go. It would be left to the intellectuals of the next century to provide the theory of biological race necessary to explain how this could happen.[119]

The World Viewed from Tultepec

By Risa Puleo

Maps help us remember how to get from one place to another. But whose idea of place do they record?

In the Indigenous Farmers of Tultepec vs. Spanish Rancher Juan Antonio Covarrubias map in the Newberry’s collection, two different interpretations of a site located in the valley of Mexico north of the capital city are present in the same document. Each interpretation is founded on two very different conceptions of what constitutes ownership and governance in this early moment in the Spanish occupation of Mexico (Figure 4.2). The map can be read in two different ways because Nahuatl, the language of the people of the Central Mexican Valley before Spanish Conquest, was written in a complex system of phonetic rebuses, ideograms, and pictographs before it was transliterated into the Latin alphabet. Thus, what a Spaniard understood in the sixteenth century, and perhaps what we, as contemporary viewers of the map, register as an image of a landscape was equally a text written in a series of image-puzzles that can be read and deciphered. Whether we look at the map as an image through European conceptions of space or as a text through Nahuatl picture-writing determines whether we see a map of a newly settled New Spain or of a recently occupied Ānāhuac.[25]

The Farmers vs. Covarrubias map is named for the two parties in the 1569 court case that settled their property dispute. Covarrubias’s sheep had intruded into the farmers’ fields and were eating their crops. The farmers appealed to the Spanish court in Mexico City to intervene and had a tlacuilo, a person trained in the arts of mapmaking and record keeping, usually a member of the Native elite, draw up the map as evidence to defend their claims.[26] The sheeps’ transgression of property boundaries is described on the map by two corrales, or pens, that the animals would return to after grazing in the hilly grasslands surrounding the valley in which Tultepec lies. The one pen within Covarubbias’s property line in the top left quadrant of the map is notably empty. But the pen at the top of the green area in the lower right-hand quadrant of the map contains a horned ram. Beneath this second pen is a handwritten note that demarcates the green area as “es de los yndios,” meaning it “belongs” to the Tultepec farmers.

This phrase is written with the same flourished penmanship in which the Spanish judge wrote his verdict atop the Indigenous-made map. It speaks directly to the Spanish readers of the map, including the judge who ruled on the case, Covarrubias, whose actions would be determined by the court, and perhaps the Tultepec farmer who acquired Spanish as a first or second language in this moment nearly five decades after Spain’s military conquest of Mexico. “Belongs to,” in the Spanish connotation, relates the idea that the Indigenous farmers of Tultepec own this area as property. The farmers of Tultepec conceptualized their place in the world, not through European concepts of property, but through ideas of sovereignty related to independent polities in a network of city-states. Terms that the historian Anthony Pagden develops in his study of empire through the ages helps us distinguish between Spanish and Native Mexican concepts of the land, and by association, who can use it, how, and under what circumstances; in other words, governance. Pagden explains how imperium, the Roman concept of empire that the Spanish adopted and employed in the Americas, is an authority that is taken by force over foreign territories. He writes, imperium assumes “long-term de facto occupation to be recognized de iure as conferring retrospective rights of[120] property and jurisdiction, no matter how illicit the original occupation might have been.”[27] Dominium, or sovereignty, by Roman terms, is the tribal rule of the people in place before occupation and relates to the individual authority held by constituencies under the umbrella of empire. But the farmers of Tultepec did not think in these terms. Rather, the Tultepecan perspective is better understood through the Nahuatl word tlalticpac. This term translates to a range of concepts related to earth: from dirt to land and the sphere of human existence, as distinct from the realms of the sky and underworld.[28] The land itself speaks through the map’s materiality and in the ways that the Tultepecans conceptualized how they belonged to it. Tlalticpac and Imperium are at a standoff in the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map.

One way that racialized power relations between Natives and settlers manifested in the early colonial period is as property disputes. Conquistadors were given land in the newly established colony, and the indebted service of the Native people living on it. Land was also granted to new settlers and missionaries by the Spanish Crown in efforts to occupy and Christianize the Americas. Much of this property passed to further generations or was sold to other Spaniards, like Covarrubias, who purchased property from the family of a conquistador at an auction.[29] In addition to creating a physical separation from Indigenous Mexicans, property ownership allowed Europeans and their descendants to capitalize upon the land, as well as the indentured servitude of Native people and the forced labor of enslaved Africans who worked it, to generate inheritable wealth. Over time, this accumulated wealth generated a racialized caste system — pictured most notably in eighteenth-century castas* paintings — in which race, class, and the capacity to own property and generate wealth are inextricably linked. Notably, many of these new residents of Mexico brought sheep with them from Spain.

We can begin to grasp the danger the sheep posed to the farmers and the reason that the farmers took Covarrubias to court by reading the Nahuatl images as a text. Nahuatl maps differ from European territorial maps in that features of a place or in a landscape are often abbreviated. For example, the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map represents a twenty-five-mile span between five towns, themselves represented by five churches, as if it were a walkable space. And that one horned ram within the green area marked es de los yndios? He is an abbreviation for the 5,000 –20,000 sheep that would have comprised a ranch such as Covarrubias’s. Multiplying that number by the thousands of new sheep ranches in the area means that by 1569, when the Farmers took Covarrubias to court, 24% of the highlands surrounding Tultepec were half-pasture, supporting upwards of 700,000 heads of sheep.[30] Within a few years, these grazing lands would become “scrub-covered badlands” when overgrazing sheep ate the prairie beyond its capacity to recover.[31] The Farmers vs. Covarrubias court case is only one of many examples of sheep-related property transgressions at this moment.[32] Across the Central Mexican Valley, Native farmers lobbied to the Spanish court system in defense of their land and their ability to generate and protect their food supply from Spanish sheep.

But Spanish courts did not mediate a universal ideal of truth and justice. Rather they judged one’s ability[121] to produce evidence in the proper forms and formats. In the early moments of occupation, the bureaucratically-minded Spanish understood pre-Conquest Nahuatl maps as city charters and took them as proof of Indigenous ownership of a territory.[33] Other communities without such documents were dispossessed and indentured to the Spanish owners who claimed their lands.[34] With less experience in producing this kind of paperwork to the standard that was acceptable to the court, Native people often lost their cases as judges defaulted to the party who was most able to uphold the formality of the court, i.e. other Spaniards who were familiar with the court’s protocol. Thus, one reason that Nahuatl map-making practices persist after Conquest is so that Native Mexicans could make written claims to the spaces they inhabited, in their moment and ancestrally.

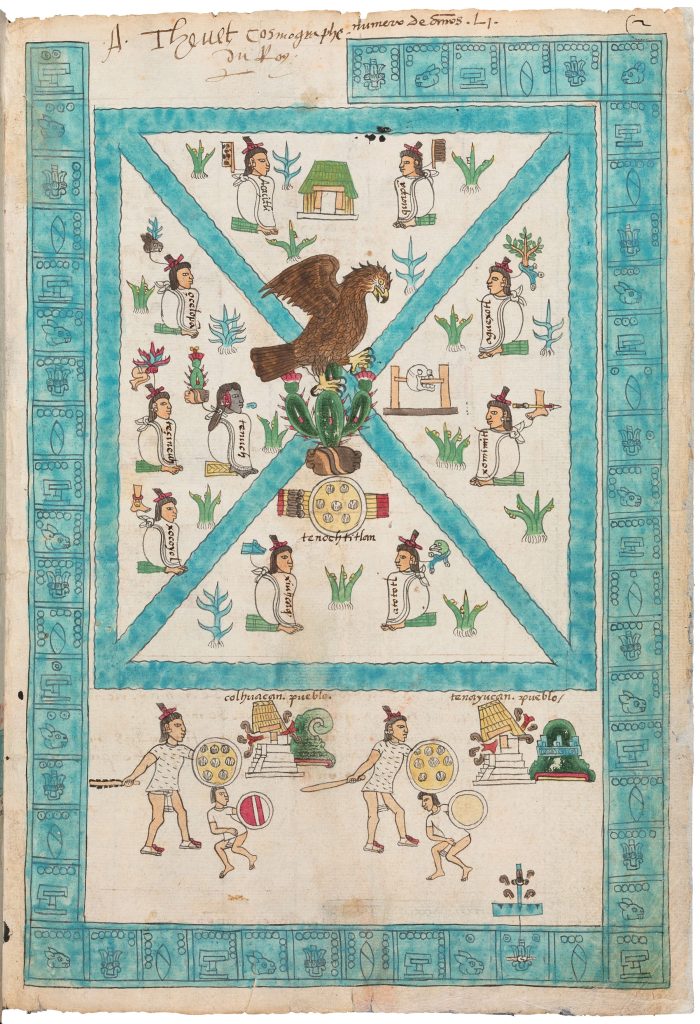

Rather than describe geography spatially, Nahuatl maps are structured according to what art historian and Nahuatl map specialist Barbara Mundy calls “the social layout of the city,” meaning Indigenous maps marked political alliances and genealogical lineages rather than territorial borders.[35] Take for examples, Codex Reese, a map made to defend the claims of a Native people in Mexico City in the mid-sixteenth century, and the Codex Mendoza, a compendium of pre-Conquest Aztec life written after Spanish occupation. The frontispiece of the Codex Mendoza is a map that represents the Aztec capital city Tenochtitlán, which in the moment in which it was written in 1541, was well into the process of becoming the capital of New Spain: Mexico City (Figure 4.6). In the center of this map, an eagle stands atop of the nopal cactus that grows out of a rock. This emblem, recognizable as the design for the contemporary Mexican flag, describes the mythopoetic divinatory sign the Mexica looked for to identify the site to build their capital city. Its inclusion on the Codex Mendoza’s frontispiece map, then, places it within a longer, ancestral, framework of history. Surrounding this emblem, ten figures are spread across four city districts. Each represents one of the ten founders of Tenochtitlán to which the city’s inhabitants could chart their genealogy. Writing about the Codex Reese, also known as the Beineke map, sociologist Pablo Escalante Gonzalbo describes the seven houses depicted on the map’s left edge not as seven literal houses, but rather the seven lineages to which the township could trace their genealogy.[36] Made in 1565, the Codex Reese charts one hundred and twenty-one land claims and Native rulership in Tenochtitlán back to 1538 (Figure 4.7). According to Mary E. Miller, an art historian of the pre-Columbian arts of Mexico, the decision to include a genealogy of governance demonstrates how the “tlatoque (Nahuatl tla’to’que’; rulers) pictured on the map still had some claim to power.”[37] Barbara Mundy expands upon Miller’s statement by showing how the tlatoque still held positions of power at the time of the Beinecke Map’s making. Over time, they would be even though they had been pushed to Native-only zones at the edge of Mexico City where they still held power within their own communities though demoted down Spain’s power structure.[38]

MS. Arch. Selden. A. 1, fol 2r, Codex Mendoza, Viceroyalty of New Spain, c. 1541–1542, pigment on paper, © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Codex Reese, sixteenth-century Mexico, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library

No figures that demonstrate the ancestry of the farmers of Tultepec are pictured on the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map, but it does communicate the map-

maker’s[122] ancestral ties to places in other, rather quiet ways. The mapmaker’s embeddedness within tlalticpac is found, first in the paper on which the image is written. To make amantl paper, the thin, flaky bark of fig and mulberry trees would have been harvested and boiled down. The resulting viscous fibers would have been laid in alternating layers to provide the paper with structure, then pounded flat into sheets. This process dates back before Spanish occupation. The Farmers vs. Covarrubias map also shows the mapmaker’s knowledge of plants and minerals of the region, specifically, how to process each variety to extract the brightest pigments to paint the map. The map’s materiality, however, would not have been legible to the Spanish reader as proof of a deep engagement with the land that the image depicted.

While the Spanish audience of the map read the text “es de los yndios” within European frameworks of property ownership, the map’s Indigenous audience would have seen the green area in which this phrase is written as an articulation of Native sovereignty as loudly as a representation of a tlatoque. I contend that the shape of the green area and its color, so different from the rest of the map, would have communicated that it “belonged” to the Indigenous farmers of Tultepec to the Native readers of the map without the written words “es de los yndios.” From the Indigenous perspective, the terms of “belonging” have a meaning radically different from the property regimes of imperium and relate more closely to the terms of tlalticpac.

Before Conquest, the Aztec people represented towns with the altepetl glyph on maps and documents. The spoken word “altepetl” is a portmanteau, combining the words atl for “water” and tepetl for “hill” to signify these basic necessities of water and land respectively needed to support life.[39] Together, “water” “hill” move beyond the objects they represent in the world to signify a polity, or governed territory, much like a city-state. Each city-state was represented in writing with the basic form of the altepetl: a green hill, occasionally depicted with swirling water issuing from its base or blooming from both sides of its green-pigmented bell-shape. Additional notation on the top or sides of the hill gives that city-state a name. For example, Muchitlan’s name translates to “Place of the Mochil” and suggests this was a place where the medicinal plant would have been found. The glyph that represents the town in pictorial Nahuatl is composed of the hill-shaped altepetl glyph topped by a representation of a four-petaled flower that resembles the cuamochil plant.[40] The name of the plant itself signifies its use: cua is the Nahuatl verb “to eat” and mochil, an abbreviation of xochitl, the word for “flower.” Thus, Muchitlan roughly translates to medicinal flower-town. To write the toponym for Tultepec a tlacuilo would place four long pointed green stems with black tips atop the same hill-shaped altepetl glyph to represent the tule plant for which Tultepec is named (Figure 4.8). The marks that distinguish Muchitlan from Tultepec each derive from looking at plants in the landscape.

Toponyms for Tultepec (Wikipedia)

After Conquest, when churches became the most significant architectural and social feature of a town after occupation, the “church” glyph replaced the altepetl in written Nahuatl. On the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map, five neighboring town are represented by five small drawing of churches. Each has an arched door, much like the doorway of Covarrubias’s hacienda in the top left corner of this map, as well as steeped roofs. These arches contrast with the pier and lintel door frames used to describe the Native houses that dot the central portion of the map. This difference in architecture also describes the divide between Spanish space and Native space in life. In addition to being the space[124] in which Indigenous Natives and settlers most often came into contact, churches were often built atop hills and mountains as the Spanish recognized the sacred significance that Aztec and other Indigenous people attached to them. The placement of the Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de Los Remedios upon Tlachihualtepetl, a Nahuatl name that identifies it as a “hand-made mountain,” in 1594 is a well-known example of an absorbed and supplanted place of Indigenous worship in the Central Mexican Valley. Yet, despite this shift in language for indicating a township from the altepetl glyph to the church glyph, art historian Barbara Mundy questions the degree to which the church actually supplanted Indigenous conceptions of community in this initial moment of settlement. She argues that churches on Indigenous-made maps in this early colonial period represent a “double-consciousness” because they are painted equally for Spanish patrons[125] and Indigenous users, in most cases under the direction of Spanish missionaries.[41]

With its distinctive hill-like shape, could the green area on the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map be a modification of the altepetl glyph? Directly translated into English, the spoken word Tultepec means “hill of Tule.” But this translation misses the depth of the written Nahuatl word. “Hill of Tule” identifies a geographic feature. But the “Altepetl of tule” relates the governing body and community established in the region where the tule grows. The “Altepetl of tule,” then, is a sovereign territory and not an owned property.

In 1569, was the meaning of the altepetl glyph loaded with the same authority as it had been pre-Conquest? Does the altepetl used here function the same way as the tlatoque deployed on the Codices Reece and Mendoza? By drawing it on the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map, did the tlacuilo activate a claim for tlalticpac, in both its literal sense as land and its more expansive meaning as the realm of the farmer’s existence? Was[126] the use of this written word a cultural memory whose full meaning was fading out of use? To what degree did the farmers of Tultepec speak from this position of sovereignty is a question to be explored. The tlacuilo’s use of the altepetl on the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map does tell us that the Tultepecans exist in a state of double consciousness, much like the map itself. Rather than the church glyph supplanting the altepetl glyph, the altepetl glyph hides on the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map in plain sight.

Nearly fifty years after the military conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Spanish residents of New Spain were becoming more aware of how Spanish law, ways of life, and animals were affecting the Indigenous people of Mexico and the environment. Perhaps for this reason, Judge Francisco Santiago de Bazán ruled in favor of the farmers of Tultepec. Other Native people who took Spaniards to court were not so lucky. The judge ordered Covarrubias “to move the corral of the said estancia [ranch] next to the road, further back behind the Indians of Xaltocán,” a neighboring Native village, thus offsetting the Farmer’s problem to another group of Indigenous people. Additionally, the Tultepecans were ordered to pay to move Corvarrubias’s corral and were also forbidden from entering Corvarrubbia’s property. They were authorized to “obtain from the lands” up to the red line “where some magueys are for the work of the said Indians” but “cannot enter . . . the common pasture.”[42] The line of maguey agave that define the Farmer’s property line would have been inedible to sheep and suggests that other plants at the borderline were utilized to deter the sheep’s transgressions.

Judge Bazán and his clerk, Gaspar Peréz, signed directly underneath the red line that delineates Covarrubias property and above the line of maguey agave that defines the limits of the Farmer’s altepetl. Within the system of the Spanish court, this signature functions as an official seal that is symbolic of Spanish authority in the region and Covarrubias’s right to property. Within the system of Nahuatl writing, the altepetl holds the same symbolic weight of authority and speaks to the continuation of markers of Native sovereignty, if not the right to self-determine one’s own life in the lands to which one belongs outside of colonial control.

From the Spanish perspective, the map defines the division between two communities and two properties based on Spanish concepts of ownership. But we also see an Indigenous village in the process of being deterritorialized by the imposition of property lines. In this way, the green area appears as a space of imprisonment surrounded on all sides by Spanish claims. From the Nahuatl perspective, we can potentially think of the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map as a treaty between two nations. Both perspectives of the Farmers vs. Covarrubias maps demonstrate how property disputes were race relations in early colonial Mexico.

Conclusion

No map is neutral. No map is entirely objective. Whether it claims to document the physical and human geography of the entire world or define the property rights of different groups in a particular locality, it is always imbued with purpose and saturated with ideology. To put it another way, it always has a point of view. Within the broad context of global colonialism, that point of view often has to do with matters of race. We see how de Fer depicts the entire world from the privileged, white, European perspective of metropolitan France, racializing the world beyond Europe in ways that would prove useful to eighteenth-century thinkers. We see how the farmers involved in the litigation against Covarrubias depict their locality from the perspective of their own[127] embattled Indigenous understanding of land, property, and sovereignty, deploying the language of Western cartography for their own ends, against the impositions of the colonial regime.

Yet we also see that while maps adopt a particular point of view, they also lend themselves to a variety of interpretations. The meaning of the Farmers vs. Covarrubias map is clearly in the eye of the beholder, and deliberately so. To the Spanish officials who were its intended audience, it speaks the language of Western property rights, the only language that has authority in a racialized colonial regime. Yet it also speaks the language of traditional Nahuatl conceptions of land and sovereignty, allowing Indigenous readers to glimpse their home in the terms of their traditional worldview. In this way, it tells us something about how the cosmologies of oppressed groups survive in racialized regimes. The de Fer maps, meanwhile, give away something that they may not intend to reveal. By acknowledging that the New World is a place that has been refashioned by colonial-era migrations, it charts the limits of its own attempt to sort the world and its people into neat continental compartments. To an early modern reader, it might speak of the need for a theory of biological race that would explain who people remained the same after moving to new places, but to today’s reader, it speaks of the arbitrariness of the project of race itself.

- The maps are available as high-resolution images on the website of the Bibliothèque National de France. See http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb406741424 (Africa); http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb40675711r (America); http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb40740247q (Asia); http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb40577015h (Europe). ↵

- Some readers may be aware that the expressions “part of the world” and “continent” are not synonymous and that, in fact, the introduction of the word “continent” into European geography is part and parcel of a significant transformation in geographical thought. In these pages, I will ignore this distinction for simplicity’s sake. ↵

- Edmundo O’Gorman, The Invention of America: An Inquiry into the Historical Nature of the New World and the Meaning of Its History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1961). ↵

- Martin W. Lewis and Kären E. Wigen, The Myth of the Continents: A Critique of Metageography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 27, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pnv6t. ↵

- Valerie Kivelson, Cartographies of Tsardom: The Land and Its Meanings in Seventeenth-Century Russia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006). ↵

- Lewis and Wigen, Myth, 35–46. ↵

- The discussion of climate theory in this paragraph and the next is based upon Nicolás Wey Gómez, The Tropics of Empire: Why Columbus Sailed South to the Indies (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 2008). ↵

- See, for example, Aristotle, The Politics, trans. H. Rackham, Loeb Classical Library 264 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1928): 564–65; and Hippocrates of Cos, Airs, Waters, Places, ed. and trans. Paul Potter, Loeb Classical Library 147 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2022): 72–73. See also James S. Romm. “Continents, Climates, and Cultures: Greek Theories of Global Structure,” in Geography and Ethnography Perceptions of the World in Pre-Modern Societies, ed. Kurt Raaflaub (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 215–35. ↵

- Here I invoke the expansive definition of race set forth by Geraldine Heng, “The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages II: Locations of Medieval Race,” Literature Compass 8, no. 5 (2011): 3, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4113.2011.00795.x. ↵

- Juan López de Palacios Rubios, De las Islas del mar Océano (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1954); Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, Demócrates Segundo, o, De Las Justas Causas de La Guerra Contra Los Indios, vol. 2a (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientâificas, Instituto Francisco de Vitoria, 1984). ↵

- Juan López de Velasco, Geografía y Descripción Universal de Las Indias, ed. Justo Zaragoza (Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 1894), 36–37. That influence would be absorbed through local foods as much as through the influence of heavenly bodies. See Rebecca Earle, The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race, and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012). ↵

- Francisco Bethencourt, Racisms: From the Crusades to the Twentieth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 63–158, traces the development of stereotypes about the four continents from which Ortelius draws and which he nourishes. ↵

- The image has been analyzed in print many times. For a recent discussion and bibliography, see Maryanne Cline Horowitz and Louise Arizzoli, Bodies and Maps: Early Modern Personifications of the Continents (Leiden: Brill, 2020). ↵

- María Elena Martínez, Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008); David Nirenberg, “Was There Race before Modernity? The Example of ‘Jewish’ Blood in Late Medieval Spain,” in The Origins of Racism in the West, eds. Miriam Eliav-Feldon, Benjamin Isaac, and Joseph Ziegler (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009): 232–64; Ben Vinson, Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018). ↵

- Guillaume Aubert, “‘The Blood of France’: Race and Purity of Blood in the French Atlantic World,” William and Mary Quarterly 61, no. 3 (2004): 439–78, https://doi.org/10.2307/3491805. ↵

- Jorge Canizares Esguerra, “New World, New Stars: Patriotic Astrology and the Invention of Indian and Creole Bodies in Colonial Spanish America, 1600–1650,” American Historical Review 104, no. 1 (1999): 33, https://doi.org/10.2307/2650180. ↵

- Pierre Boulle, Race et Esclavage Dans la France de l’Ancien Régime (Paris: Perrin, 2007), 49–50. ↵

- Benjamin Braude, “The Sons of Noah and the Construction of Ethnic and Geographical Identities in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods,” William and Mary Quarterly 54, no. 1 (1997): 103–42, https://doi.org/10.2307/2953314. ↵

- D. E. Mungello, The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500–1800, 3rd ed. (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2009), 143–44; Michael Keevak, Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011). ↵

- Cited in Lewis and Wigen, Myth, 30. ↵

- Arthur Gobineau, The Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races, trans. Henry Hotze and Josiah Nott (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1856), 341–43. ↵

- Gobineau, Moral, 149–51. ↵

- Sue Peabody, “There Are No Slaves in France”: The Political Culture of Race and Slavery in the Ancien Régime (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 60–70. ↵

- Valerie Traub, “Anatomy, Cartography, and the New World Body, Geographies of Embodiment in Early Modern England,” in Geographies of Embodiment in Early Modern England, eds. Mary Floyd-Wilson and Garrett A. Sullivan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198852742.003.0004 ; Valerie Traub, “Mapping the Global Body,” in Early Modern Visual Culture, eds. Peter Erickson and Clark Hulse, Representation, Race, and Empire in Renaissance England, New Cultural Studies (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), 44–97; Valerie Traub, “History in the Present Tense: Feminist Theories, Spatialized Epistemologies, and Early Modern Embodiment,” in Mapping Gendered Routes and Spaces in the Early Modern World, ed. Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2015), 15–53; Valerie Traub, “The Nature of Norms in Early Modern England: Anatomy, Cartography, ‘King Lear,’” South Central Review 26, no. 1/2 (2009): 42–81, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40211291. ↵

- Ānāhuac is the Indigenous name for the lands the Spanish declared “New Spain” at conquest that are presently called Mexico. In Nahuatl, the Ānāhuac means “Place Surrounded by Waters,” a name that signals the lake that once filled the basin of the Central Mexican Valley and connected life across the Aztec Empire. Barbara Mundy, “Mapping the Aztec Capital: The 1524 Nuremberg Map of Tenochtitlán, Its Sources and Meanings,” Imago Mundi 50, no. 1 (1998): 15, https://doi.org/10.1080/03085699808592877. ↵

- The Nahuatl word for “scribe” translates literally to mean equally both “painter” and “writer” and points to the ways in which image and text are interchangeable. ↵

- Anthony Pagden, “Fellow Citizens and Imperial Subjects: Conquest and Sovereignty in Europe’s Overseas Empires,” History and Theory 44, no. 4 (2005): 30–31 https://www.jstor.org/stable/3590856. ↵

- John F. Schwaller, “The Ilhuica of the Nahua: Is Heaven Just a Place?,” The Americas 62, no. 3 (2006): 391–412, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4491090. ↵

- Catalogo, resumen e indices de Protocolos, 30 April 1574, fol. 695v.; see Shirley Cushing Flint, No Mere Shadow: Faces of Widowhood in Early Colonial Mexico (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2013), 119n33. ↵

- Elinor Melville includes the data she collected about the number of sheep per decade found in multiple subregions of the northern area of the Central Mexican Valley over the sixteenth century in a series of charts included in chap. four of A Plague of Sheep: Environmental Consequences of the Conquest of Mexico (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 78–115. ↵

- Melville, Plague of Sheep, 100. ↵

- Melville’s Plague of Sheep is the best source for all sheep-related lawsuits in colonial Mexico. ↵

- Barbara Mundy, The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geographias (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 166. ↵

- Kelly S. McDonough writes of primordial land titles — a narrated version of drawn maps — in the Chaco region of the central Mexican Valley, southwest of present day Mexico City, in “Plotting Indigenous Stories, Land, and People: Primordial Titled and Narrative Mapping in Colonial Mexico,” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 17, no. 1 (2017): 1–30, https://doi.org/10.1353/jem.2017.0003. See also Stephanie Wood’s discussion of primordial titles in Transcending Conquest: Nahua Views of Spanish Colonial Mexico (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003). ↵

- Mundy, Mapping of New Spain, xvi. ↵

- Pablo Escalante Gonzalbo, “On the Margins of Mexico City: What the Beinecke Map Shows,” in eds. Mary Miller and Barbara Mundy, Painting a Map of Sixteenth-Century Mexico City: Land, Writing, and Native Rule (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 101–110, 101. ↵

- Mary E. Miller and Barbara E. Mundy, eds., Painting a Map of Sixteenth-Century Mexico City: Land, Writing, and Native Rule (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012). ↵

- Barbara Mundy, “Crown and Tlatoque: The Iconography of Rulership in the Beineke Map,” in Painting a Map, eds. Miller and Mundy, 177–178. ↵

- Elizabeth Boone Hill, “Glorious Imperium: Understanding Land and Community in Moctezuma’s Mexico,” in Moctezuma’s Mexico, eds. Pedro Carrasco and Eduardo Matos Moctezuma (Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1992), 161. ↵

- Mundy, Mapping of New Spain, 146. ↵

- Mundy, 68–74. ↵

- Author’s translation of the Spanish text written on the map. ↵

angular distance of a place North or South from the Earth’s equator

person who maps the general features of the celestial and terrestrial worlds

learned official in the former Chinese Imperial civil service

northernmost region of Finland

ornamental frame containing text

Spanish colonizer in the Americas, especially in sixteenth century Mexico and Peru

riddle representing words or syllables through pictures of objects or through symbols that sound like the intended words or syllables

non-verbal symbol used to represent a concept in a system of writing

to translate a word into a different alphabet (for instance an Arabic word into the Latin alphabet)

quarter divided from other quarters by a rectangular coordinate axis

Latin American painting from the eighteenth century representing several patterns of racial mixing in a hierarchical manner

abridgement or summary of a longer work

relative to the creation of myths

relative to prophecies

scholar studying the development, structure, and functioning of society, social institutions, and social relationships