Fashioning Racial Materiality in Nicolas de Nicolay’s Representations of Jews

M. Lindsay Kaplan and Dana E. Katz

[Print edition page number: 21]

This essay intervenes in early modern critical race studies by advancing an intersectional argument for racial materiality, that is, the formation of racial identity through material goods, rather than, alongside, or in addition to, physical markers. Kim F. Hall’s generative Things of Darkness lays the foundation for this exploration, as it has for so many others, in her consideration of material objects serving as signifiers of racial difference through aristocratic acts of display and exchange.[1] While somatic characteristics appear permanent and intrinsic, in contrast to clothing/accessories that can be alternatively attached to or detached from the body, both function metonymically to equate materiality with interiority. Furthermore, many of the early texts that underpin Western racism imagine bodies, like clothing, to be as susceptible to change: classical views on the appearance and constitution of the human body understood it as transformed by diet, climate, and age. Christian scripture avers that one may alter external appearance to hide an evil interior (Matt. 23:27–29),[22] while patristic associations of Ethiopians with sin and the demonic also assumed the capacity of repentance and redemption to whiten skin. For centuries up through the early modern period, physicians, theologians, and poets affirmed the shaping power of maternal imagination to change the appearance of unborn children. Thus, the receptivity of the body to change, including through its fashioning by clothes, already circulates through early racializing discourses.

Drawing on recent work in premodern racialization of gendered religious others, we focus on a Christian tradition of coordinating Jewish and Muslim racial identities. In particular, we attend to the complex relationship of clothing to medieval and early modern hierarchized identity, ecclesiastical and temporal laws imposing a degrading marking of Jewish and Muslim clothing relative to that of Christians, and early modern representations of male and female Jews. Our analysis considers the visual and textual portrayals of Jews inhabiting Ottoman lands in Nicolas de Nicolay’s Les quatre premiers livres des navigations et pérégrinations orientales (The Nauigations, Peregrinations and Voyages, made into Turkie).[2] The Navigations, a widely circulating hybrid costume book and travel narrative, includes four visual representations of Jews.[3] Most of the scholarship on Nicolay to date focuses on the representation of Muslims or offers a partial consideration of the representation of Jews. We contribute to the critical conversation with a systematic analysis of the compensatory interplay of text and image that demonstrates Nicolay’s advancement of a racial theology positing an inherent infidel inferiority relative to Christians. The Navigations strategically plays on similarities and distinctions in Jewish and Muslim clothing in an attempt to visualize inherent Jewish subordination in an Ottoman context that problematically undermines the divine superiority of Christianity.

Racialized and Gendered Religious Identities in Christian Hierarchy

Our theorization follows the work of Ania Loomba and others in its assumption that all racism results from cultural construction, whether through discourses of bodily composition (which always have social significance and connote inner states) or other authoritative epistemes, especially the theological, given the centrality of religion for forming premodern identity.[4] We define racism as a systemic ascription of inherent inferiority to one people by another.[5] In the West, Christianity provided a powerful logic in the creation of subordinated racial identities, initially for Jews and subsequently for Muslims, coordinating the latter into subjugating tropes established for the former.[6] The Christian belief that God punished the Jews’ alleged murder of Jesus with a spiritual enslavement operated as a racializing rationale in ascribing inherent inferiority to Jews. Although the advent of Islam postdated the death of Jesus, medieval Christianity’s[23] correlation of Muslim identity with that of the Jews produced a discourse of hereditary guilt that racialized both groups as inherent inferiors to Christians.[7] This theological doctrine shaped canon law, which frequently included Muslims in rulings about Jews with the objective of ensuring the legal and social subordination of both groups to Christians.[8] An anxious perception that Jews and Muslims challenge the imagined divine hierarchy situating Christians on top motivates the characterization of “infidel” dominance as a sinful and demonic threat.[9]

Medieval Western Christianity produced ostensibly conflicting accounts of the relationship between Muslims and Jews relative to Christians; however, all shared the aim of subordinating non-Christians to the true faith. On the one hand, the “historical” event of the crucifixion gave rise to an imagined contemporary alliance between Jews and Muslims, in which the latter secretly instigated Muslim violence against or resistance to Christianity. Christians falsely accused Jews of conspiring to betray the city of Toulouse to Muslims or directing the Muslim caliph who ordered the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem.[10] Alternatively, medieval authors such as Jacques de Vitry (c.1160–1240) perceived Muslims as enforcing God’s subjugating punishment of Jewish sin: “The Saracens [Muslims] among whom . . . [Jews] dwell hate and despise them more than the Christians; . . . [Jews] are the serfs and slaves of the infidels, and are only suffered to dwell among them in the lowest station of life.”[11] The Christian coordination of “infidel” faiths, whether stressing Jewish enmity in conspiracies with Muslims or emphasizing subordination perpetrated by Muslims, serves to justify and realize the punishing status of racialized Jewish inferiority.

Even while early modern Christians developed more nuanced attitudes towards both Muslims and Jews arising from increasing contact, changing theological doctrines, and economic imperatives, medieval tropes continued to circulate.[12] Awareness of Muslim military and economic power and assumptions about the Jews’ support of these capacities effectively repeated medieval discourses registering anxiety over “infidel” dominance. The familiar fantasy of hostility between Muslims and Jews appears in accounts representing Muslims as violent “barbarians” attacking Jews.[13] Fears of Muslim-Jewish plots similarly continue to motivate false charges that Iberian Jews settling in Ottoman lands provided key arms-producing intelligence to Muslims.[14] Several forgeries advanced the view that Jews took advantage of their relative religious freedom under the Ottomans to conspire with hidden Iberian Jews; one allegation asserted that Ottoman Jews instructed converted Jewish physicians in Iberia to murder their Christian patients. Some early modern authors argued that the Jews’ malign influence on the Ottomans contributed to God’s providential plan of an apocalyptically decisive Christian[24] victory over Islam.[15] While these charges advance clearly contradictory views, they all imagined a coordinated degradation, and thus racialization, of Jews and Muslims relative to Christians.

Other medieval and early modern fantasies coordinate Muslim and Jewish racial identities in narratives that portray “infidel” women as “fair,” the designation of white beauty for Christian women.[16] This appearance, often taken as an indicator of infidel women’s willingness to convert to Christianity, nevertheless renders them problematically indistinguishable from Christian women. While Jewish invisibility can indicate the successful subjugation of Judaism by Christianity through supersessionary erasure, conversion, or expulsion, it also suggests a continued Jewish threat rendered even more dangerous in its hidden state.[17] Furthermore, a lack of differentiation in representations of Jewish and Christian women effectively erodes the superiority of the latter over the former. The almost invisible appearance of non-Christian women inflects the ways clothing and accessories both mark and unmark their identity, creating hierarchical crises, as we will discuss below.

Clothing, Racial Materiality, and Religious Identity

In analyzing racial materiality through the medium of clothing as depicted in early modern images of Jews, we are indebted to the scholarship of Ann Rosalind Jones and Peter Stallybrass, who demonstrate the constitutive force of clothing for the early modern understanding of identity. Clothes possess agency in that they shape, not merely reflect, the persons of their wearers. Jones and Stallybrass point to the practice of investiture as a profoundly significant social practice “through which the body politic was composed . . .. For it was investiture, the putting on of clothes, that quite literally constituted a person as a monarch or a freeman of a guild or a household servant. Investiture was . . . the means by which a person was given a form, a shape, a social function, a ‘depth.’”[18] They argue that in early modernity, “clothes permeate the wearer,” materializing a person’s essential self. However, this formational function of clothing, like all social constructs, is susceptible to falsification, even as it attempts to stabilize identities and relationships; clothes “are bearers of identity, ritual and social memory, even as they confuse social categories.”[19] Furthermore, since garments could be exchanged for money, their economic value increases their power to shape or dissolve identity; hence, clothing paradoxically materialized social standing even as it circulated as a commodity.[20]

While clothing both organizes and disorganizes social status, including gender and class within a nation, it also serves as a lens for understanding other national and religious cultures. Valerie Traub develops a nuanced account of clothes worn by figures represented in early modern maps, which place

the human form . . . on a conceptual grid, localized not only by the land it inhabits, but by what the early moderns called habit. Derived from the[25] Latin for ‘holding, having, ‘havior,’ habit in the period signified ‘the way in which one holds or has oneself . . . a) externally; hence demeanor, outward appearance, fashion of the body, mode of clothing oneself, dress, habitation; [and] b) in mind, character, or life; hence mental constitution, character, disposition, way of acting, comporting oneself.’ Habit thus synthesizes the separate, yet closely related concepts, costume and custom, manners and morals.[21]

Here again, clothing manifests interiority, an essential self.[22] The advent of the costume book in the late sixteenth century served to standardize people of diverse regions of the world and emphasize socio-religious differences, creating an abstracted vision of a world that fostered social stereotypes.[23] However, clothing simultaneously demonstrates the possibility of disrupting the relationship between exterior and interior. As Diane Owen Hughes argues, costume books could also evince a “‘bricolage of fashion’ that celebrates and encourages the cross-cultural contact of clothes, a ‘miscegenation’ that mirrors the aesthetic intermingling of clothing styles promoted by the fashion industry itself.”[24] Even as changing fashions eluded representation, nevertheless “printed costume books sought to normalize and categorize regional dress according to strictly defined social, political, and gendered classifications.”[25] We argue that, like premodern somatic constructions that sought to fix personal or group identities within a social or global order, clothing lends itself to processes of differentiating and organizing cultural hierarchies. However, as we shall see, visual and textual depictions of similarities and distinctions in clothing grapple with shifting signifiers in attempts to fix subordinated racialized and gendered identities.

The history of the racialization of Jewish and Muslim identity in the Christian West operates in part through the medium of clothing.[26] This reflects the difficulty of manifesting the inherent inferiority of sin that leaves no visible indication on “infidel” bodies. The Fourth Lateran Council (1215) promulgated five canons specifically regulating Jews’ behavior, all attempting to prevent “any who blaspheme against Christ [from having] . . . power over Christians,” Jews as well as “pagans,” i.e., Muslims.[27] As Nicholas Vincent observes, Canon 68 ordering Jews and “Saracens” to wear distinguishing clothing emerges in the context of attempts to regulate the attire of Christian clergy; strikingly, the law prescribing “infidel” apparel constituted “the first pan-European sartorial legislation.”[28] Clothing legislation operates here by imposing signs on otherwise unmarked bodies to create and enforce social stratification; Jewish and Muslim indistinguishability from Christians raises the scandalous[26] possibility of inferiors exercising power over their spiritual and social superiors.[29] The canon accuses Jews and Muslims of using clothing to insult Christians and Christianity during Holy Week: “[infidels] do not blush to go out . . . more than usually ornamented [ornatius], and do not fear to poke fun at the Christians who display signs of grief at the memory of the most holy Passion.”[30] The term ornatius, connoting splendid attire as well as an honored status relative to the mourning Christians, signals the blasphemous hierarchy inversion effected through clothing. Conversely, the degrading force of clothes for racial formation registers in the numbers of Jews across Europe who sought to avoid this decree through paying fines; even popes admitted that the requirement to wear distinctive garments might expose Jews to violent attacks.[31]

Medieval visual imagery also relied on clothing as a means of materializing the racial identity of infidel men and women. In her analysis of the distinctive “Jewish hat,” Naomi Lubrich documents “The quantity and complexity of anti-Jewish iconography featuring hatted Jews starting in the twelfth century;” strikingly this artistic convention contributes to subsequent clothing legislation requiring Jews to wear hats as another type of identifying clothing or badge.[32] Medieval artists also employ distinguishing head-coverings to designate Muslim identity.[33] However, some images use a turban to depict both Muslims and Jews; while primarily an indicator of Muslim identity, its appearance on the heads of Jews suggests an allegiance of both groups against Christians.[34] Furthermore, even though Canon 68 applied to both male and female Jews and Muslims, some localities required Jewish women to display additional signs specific to their gender. Diane Owen Hughes’s study of medieval and early modern Italian visual representations demonstrates how earrings operated as a gendered Jewish marker that was associated with Eastern and Islamic opulence as well as with the “sartorial splendor” of sex workers.[35] Nicolay’s use of clothing and jewelry in images and texts emerges out of a visual tradition relying on material markers to create gendered religious hierarchies.

Nicolay’s Jews

While Nicolas de Nicolay’s Navigations combines the genres of travel narrative and costume book, his images may constitute the more influential aspect of this work, which circulated in multiple subsequent editions and translations.[36] Although the text[27] purportedly narrates Nicolay’s first-hand account of his travel to Istanbul in 1551 as part of a French embassy to the Ottoman empire, his imagery displays greater originality than his descriptions, which iterate views of contemporary authors.[37] Nevertheless, as we will demonstrate, the interplay between text and image supports a larger polemic that advances Christian global domination.[38] Nicolay envisages that the “intrinsically human and political activities” of travel and communication will produce a utopia of global exchange and co-existence under the rule of Christianity.[39] However, contemporary political and theological realities threaten this aspirational Christian superiority; during his travels he encounters first-hand forms of Christian subordination to Muslims, including relegation of Ottoman Christians to the status of non-believer or zimmi, a social and political inferior.[40] Nicolay also devotes attention to the troubling hierarchy inversions posed by Jews, insofar as zimmi legislation effectively erases the proper gradation by equalizing Christians with inherently inferior Jews. Even more blasphemously, the absence in the Ottoman context of discriminatory regulations such as those enforced in the Christian West enables Jews to thrive and even excel their religious/racial superiors precisely in the essential fields of language and travel.[41]

In order to counter this threat, the Navigations deploys racializing discourses of Christian doctrines in concert with ethnographic interest in the Ottoman dress to materialize inherent Jewish inferiority. The illustrations codify the customs and costumes of daily life in sixty woodcuts, from shrouded Turkish women walking to the baths and cavorting men intoxicated by opium to a janissary and Arab merchant in full regalia.[42] Nicolay attempts to impose order through clothing, producing gradations across multiple taxonomies including class, gender, and religion, whether within Islam, between Muslims and zimmis, or between Christians and Jews. Nicolay portrays four Jews of different genders, ages, and, in some cases, professions: a Jewish physician, a Jewish merchant, a Jewish woman, and a young Jewish maiden. For the most part, neither the engravings nor woodcuts in the various early modern editions capture the colors of their attire, a significant feature in identifying the quality of the garments and the ethnicity of their respective[28] wearers.[43] Compensating for the lack of chromatic detail in the printed image, the text specifies color in dress, referencing zimmi status in order to materialize Jews’ inherent subordination.[44] However, Nicolay creates a complex interplay between word and image, supplementing accounts of Levantine Jewish success with degrading visual signs in the illustrations, sometimes adducing verbal evidence of ascribed inherent Jewish inferiority when images insufficiently convey their degradation. In viewing first-hand the thriving Ottoman Jewish community, Nicolay seeks to expose this success as merely apparent by employing a combined verbal and visual representation of clothing that reveals the Jews’ true lesser status.

Nicolay’s image and text draw on similarities and differences in clothing to assert the Jews’ inferior status in Muslim society. However, in his portrayal of the Jewish physician with its accompanying text, he grapples with the problem of Jews excelling Christians and Muslims alike in multilingual fluency. In his chapter “Of the Phisitions of Constantinople,” he explains, “the reason wherefore in this Arte . . . [Jews] doe commonly exceede all other nations, is the knowledge which they haue in the language and letters, . . . [in which] haue written the principall Authours of . . . the sciences meete and necessarye for those that study phisick.”[45] The Jews’ familiarity with multiple languages accounts for their success, to the extent that the physician attending upon the sultan was a Jew: “muche esteemed, aswell for his goods, knowledge, and renowne, as for honour and portlinesse.”[46] Nicolay registers Jewish difference here, but this is an elevating, rather than derogating distinction, demonstrating how linguistic fluency privileges them relative even to their Turkish peers.

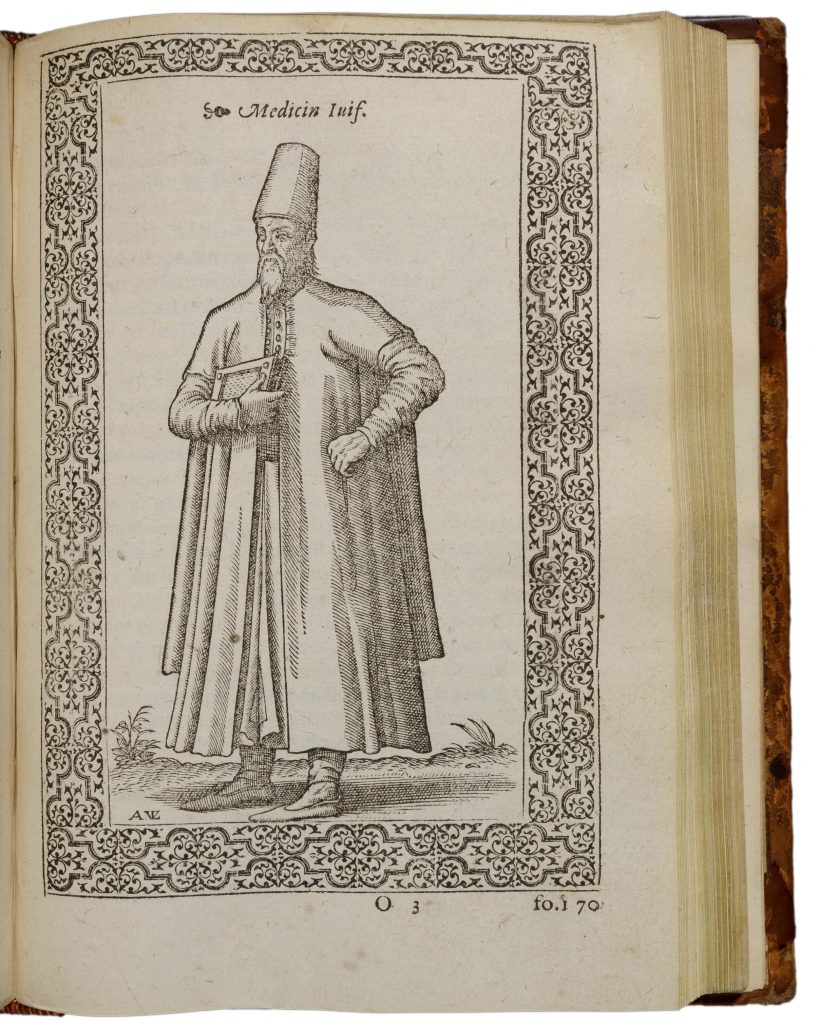

In order to counter this improper superiority, Nicolay combines text and image to portray the Jew’s true inferiority: “As for the dress of Turkish physicians, there is no difference from that of the common people. But there is a difference for those of Jewish physicians: because instead of the yellow turban, belonging to the Jewish nation, they wear a high pointed hat, colored in scarlet red, of the type as one can see in the following portrait”[47] (Figure 2.1). While Muslim physicians resemble the common people in dress, Jewish physicians wear a distinctive red hat. Nicolay’s description of it includes a reminder that Jews normally wear the demeaning yellow turban, effectively equating both as signs of Jewish inferior difference, even while suppressing the fact that Islamic law also marked Christian subordination through clothing.[48] The accompanying image shows the Jewish physician outfitted in a long caftan tied at the waist, covered by a robe, and donned in a tall hat, denoting his religion and vocation. In choosing to depict only a Jewish doctor, Nicolay singles him out as different, not by virtue of his skill as physician, but as subordinated in Ottoman society as a social inferior. The text and image portray the red cap as a[29] sartorial signifier of race that diminishes Jewish bodies through the cut and color of a material object.

Nicolas de Nicolay, “Jewish Physician” (170r) Les navigations pérégrinations et voyages, faicts en la Turquie, Antwerp, 1576, Newberry Library, Wing ZP 5465 .S587

However, Nicolay employs another visual strategy of vestimentary subordination in creating an identification between Jews and Muslims. While Ottoman dress culture constructed class hierarchies, it also homogenized the sartorial practices between Muslims and non-Muslims. Nicolay renders his Jews as nearly indistinguishable from Muslims, in face and in fashion, reiterating how the garments of Jewish men are similar to those of “other nations of Leuant.”[49] Nicolay’s image of the Jewish physician offers an example of this visual strategy that clothes Jews and Muslims in the same attire to suggest shared enmity to Christians. While this appears to contradict the illustration of distinctive clothing to indicate the Jews’ subordinated difference, in fact both methods share the goal of materializing Jewish inferiority. With the exception of his hat, the Jewish physician’s long-belted caftan and robe resembles that of his Muslim colleagues as well as the Muslim “common people.” The portrayal of an Islamicized Jewish physician visualizes the myth of “infidel” conspiracy that animates charges like the one that Ottoman Jews colluded with hidden Iberian Jewish doctors to murder rather than heal Christian patients. While this falsehood developed in the medieval period, it continued to circulate throughout early modern Europe.[50] The interpellation of Muslims into the category of deicides, expressed in terms of the military threat they posed to Christians that Nicolay himself advances, ramified myths of Jewish-Muslim conspiracies. In representing a Jewish physician in Muslim attire, Nicolay employs a material mark of clothing to imply and reveal a shared threat to Christian life that proves inherent non-Christian inferiority.

In addition to coordinating Jewish-Muslim enmity through cloth, Nicolay reprises the theme of Jewish linguistic facility to disclose its role in strengthening Ottoman military power. In his extended chapter on Jewish merchants, he accuses recently immigrated Iberian Jews,

who to the great . . . damage of the Christianitie, haue taught the Turkes . . . to make artillerie . . . and other munitions . . .. [T]hey haue also the commoditie & vsage to speake and vnderstand all other sortes of languages vsed in Leuant, which serueth them greatly for the communication and trafique . . . with other strange nations, to whom oftentimes they serue for . . . interpretours.[51]

These Jews allegedly share their expertise in the manufacture of weapons with their Muslim hosts, thereby increasing the military threat against Christianity.[52] This fabricated charge builds upon fears of Jews instigating Muslims to join with them in a conspiracy to kill Christians. Again, the Jews’ proficiency in multiple languages assists them in communicating this dangerous information to Muslims. Nicolay limns a double threat here, insofar as Jewish linguistic ability not only renders them superior to Christians but also enables a conspiracy with Muslims against the true Church; taken together these challenges to God’s will display Jewish inherent sinful inferiority.

The chapter on merchants also brings into focus the fact that Jews excel Christians at the other necessary action required for the fulfillment of Nicolay’s utopian vision, that of global travel. However, Nicolay deploys racial theology to transform the relative advantage of Jewish dispersal into a cursed chastisement. Jews do[30] not fulfill the imperative of travel ordained by God to humans, but experience exile as a divinely imposed punishment. He advances the familiar claim that the Jews crucified Jesus:

and charging themselues with the offence & sinne committed towardes his person, wrote vnto Pilate, hys blood bee vppon vs and our children, [Matt 27:25] and therfore their sinne hath followed them and their successours throughout al generations, . . . for since their extermination and the vengeaunce vpon Ierusalem vnto this present day, they . . . haue alwayes gone straying dispearsed and driuen awaye from Countrie to countrie. And yet euen at this day in what region soeuer they are permitted to dwell vnder tribute, they are abhorred of God and menne.[53]

Nicolay iterates the medieval Christian logic that racializes Jews, citing the verse from Matthew proving Jewish hereditary guilt that elicits a divine curse of repeated expulsions, extending to the contemporary moment. God’s hatred, shared by the people of every nation, continues in the punishment of perpetual inferiority, as countries only permit Jews residence “vnder tribute,” that is, as permanent inferiors.[54]

However, this poses another disturbing equivalence for Nicolay, insofar as the Ottomans impose a subordinate status of zimmi on Christians as well as Jews, effectively reducing both to the same degraded level. By situating the Jews’ payment of tribute within the context of hostile Christian discourse of divine punishment, Nicolay attempts to distinguish Jewish tributary status from that of Christians. However, both are subject to a tax imposed on non-Muslims, as Nicolay explains in his discussion of religion of the Armenians: “they are christians, hauing their church and ceremonies a part, as all other not being Turks haue, al which the great Lord doth permit, to liue according to their minde, their lawe and religion, paying vnto him the Carach or tribute of a Ducate for euery head by the yeere.”[55] Other conditions imposed on zimmis included wearing distinguishing garments of specific colors. In his description of Ottoman Greece, Nicolay writes of Salonica’s religious plurality in chromatic terms:

This citie is as yet most ample & rich, inhabited of thre sundry sorts of people, to wit, Christian Greeks, Iewes, & Turkes: but the number of Iewes (being mercha[n]ts very rich) is the greatest: and there are 80 synagogues: their attire on their head is a yellow Tulbant safroned, that of the Grecian christians is blew, & that of the Turks white, for that through the same diuersitie of colors, they should be known the one from the other, & are all clothed in long gownes as the other Orientals are.[56]

According to Nicolay, the flowing robes of Muslims, Jews, and Christians signified their sartorial sameness. Only the color of turban cloth distinguished between the indiscernible bodies of the Ottoman Empire. While emphasizing similarity and presenting difference neutrally, Nicolay suppressed the fact that the colors permitted to both Christians and Jews signaled their shared subordination to Muslims, the only group who could wear white headgear. These moments where mutual zimmi status threatens the hierarchy between Christian and Jew animate Nicolay’s strategy in materializing Jewish subordination.

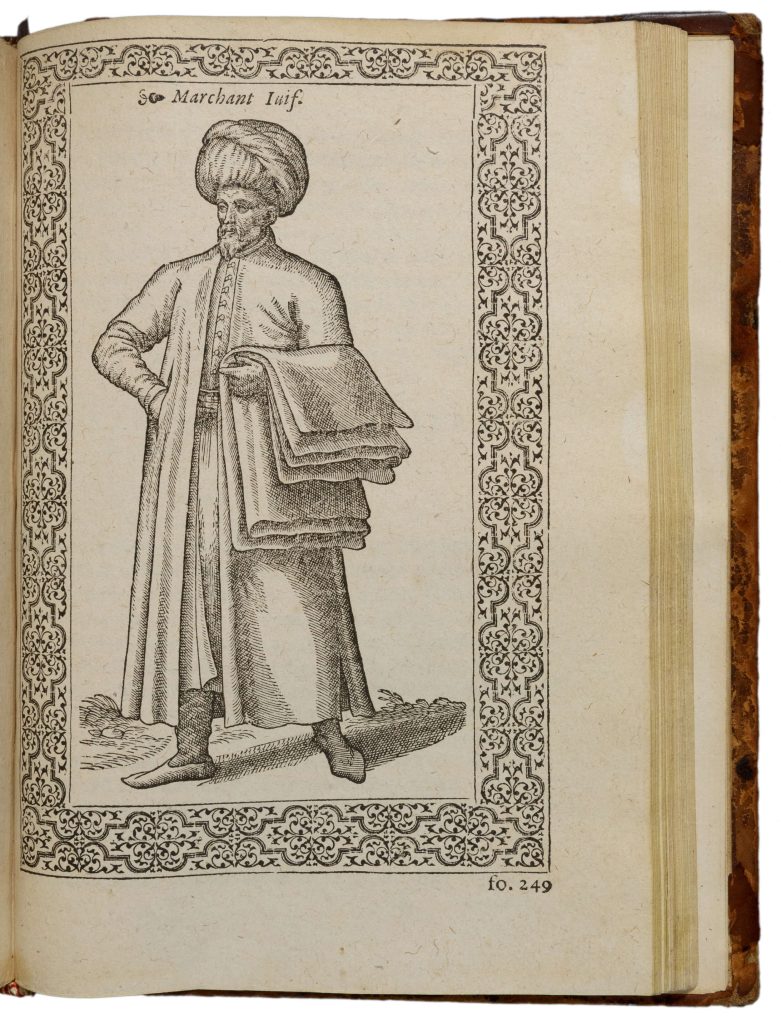

Nicolay’s image of a Jewish merchant affords visual and textile signifiers, in addition to text, to represent racialized subordination (Figure 2.2). A compensatory[32] degradation appears in his representation of a Jewish merchant dressed in long shalvar trousers and a belted caftan topped by a long robe.[57] The text elaborates on this image:

The Iewes which dwell in Constantinople . . . & other places of the dominion of the great Turke, are all apparrelled with long garments, like vnto the Gretians, and other nations of Leuant, but for their mark and token to be knowen fró[m] others, they weare a yealow Tulbant . . .. This which I haue drawen out is one of those that carie cloath to sell through the citie of Constantinople.[58]

Nicolas de Nicolay, “Jewish Merchant” (249r), Les navigations pérégrinations et voyages, faicts en la Turquie, Antwerp, 1576, Newberry Library, Wing ZP 5465 .S587

Nicolay’s Jewish merchant wears a yellow turban, revealing his ubiquitous subservience to Muslims. However, he shares the rest of his apparel as well as a subordinated zimmi status with Christian Greeks, again threatening to destabilize the racial/religious hierarchy.

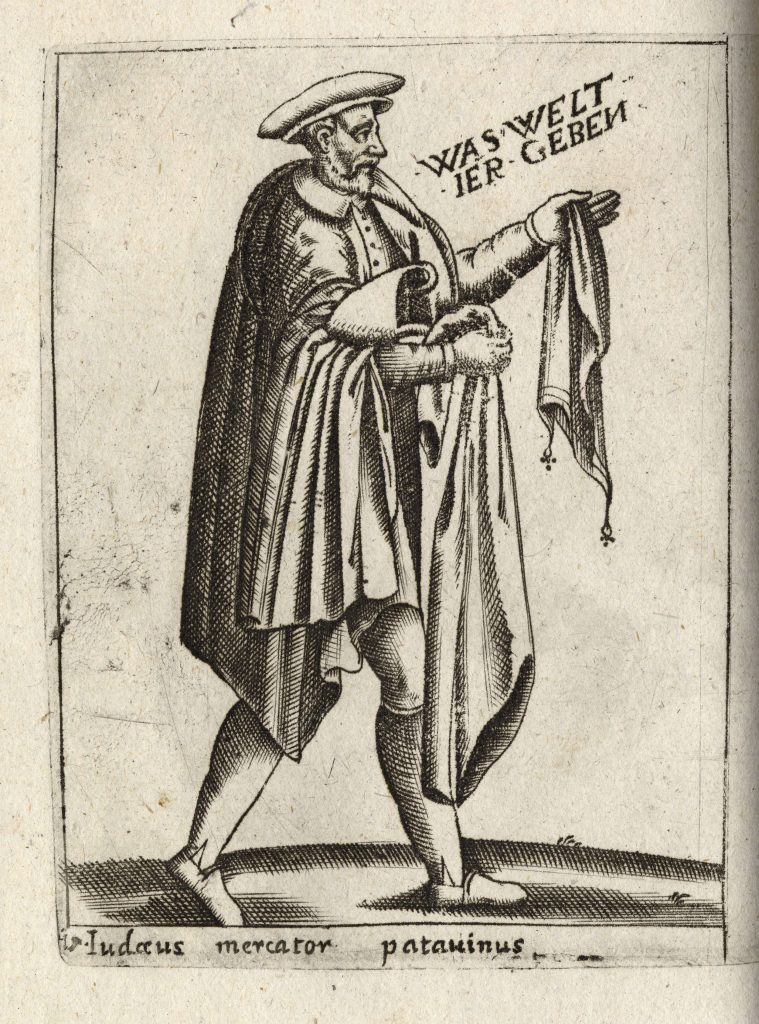

Nicolay therefore introduces another material subordination in the image of the Jewish merchant, not in the clothes he wears, but in the cloth he carries, draped over his left arm. Although he describes the Jews as virtually monopolizing all trade in Constantinople, he chooses a textile to represent their primary commodity.[59] Jewish merchants living in the Ottoman Empire sold spices, jewels, and clothing accessories, as well as luxurious cloth of wool, silk, brocade, and velvet.[60] However, the depiction undercuts the Ottoman Jews’ aforementioned participation in multiple trades by creating a visual resonance with Christian societies, which restricted Jews to a few professions, including the lending of clothes and money.[61] Clothing served as collateral to secure loans on which the creditor could charge interest, and Nicolay’s image here may reinforce his repeated textual condemnation of Jewish usury, another racializing degradation.[62] Nicolay’s depiction of a Jewish merchant anticipates that of Pietro Bertelli in his Diversarum nationum habitus (1594–1596, Figure 2.3), in which a Paduan Jewish peddler holding swathes of textiles publicly exclaims, “What do you want to give” (“Was welt ihr geben”).[63] Nicolay’s Jewish merchant does not carry a used garment in his arms, but the depiction and description of him as carrying “cloath to sell through the citie of Constantinople” (131v) undermines the initial account of Jewish trade in the city.[64] In suggesting the more familiar restricted economic status of Jews in early modern European countries, Nicolay’s text and image work in concert to import Christian hierarchy and enforce a racializing subordination of Jews not adequately realized by the Ottomans.

Pietro Bertelli, “Jewish Peddler” (Plate 15), Diversarum nationum habitus (1594–1596), Folger Library, GT513 B4 Cage copy 1 vol. 1

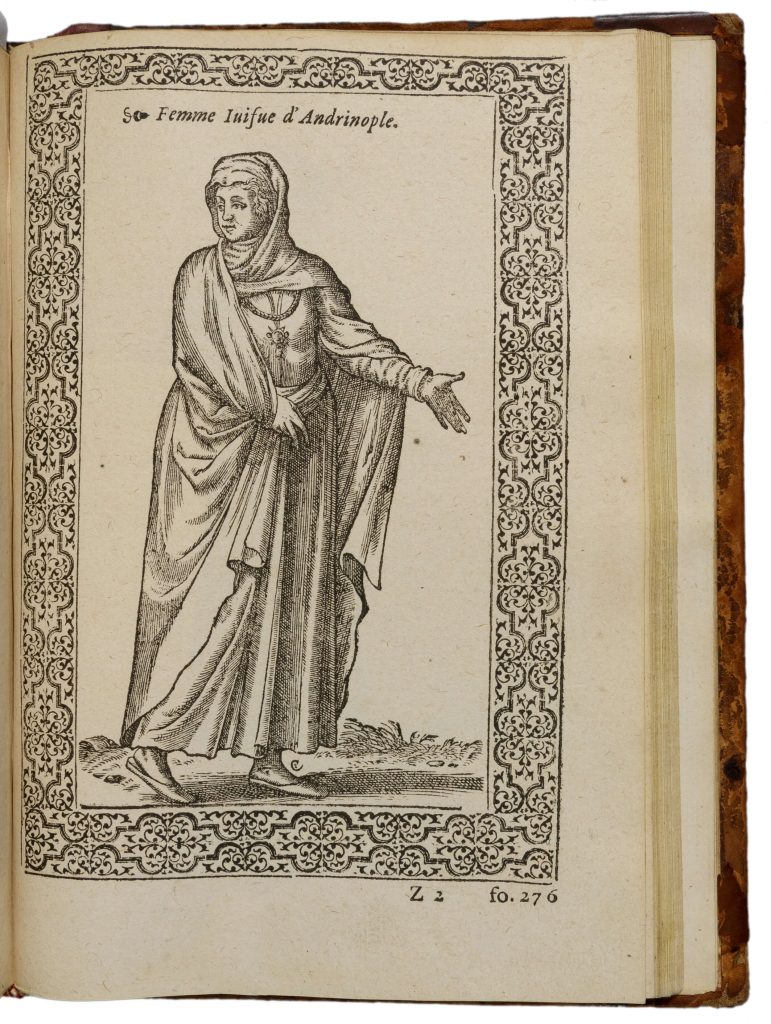

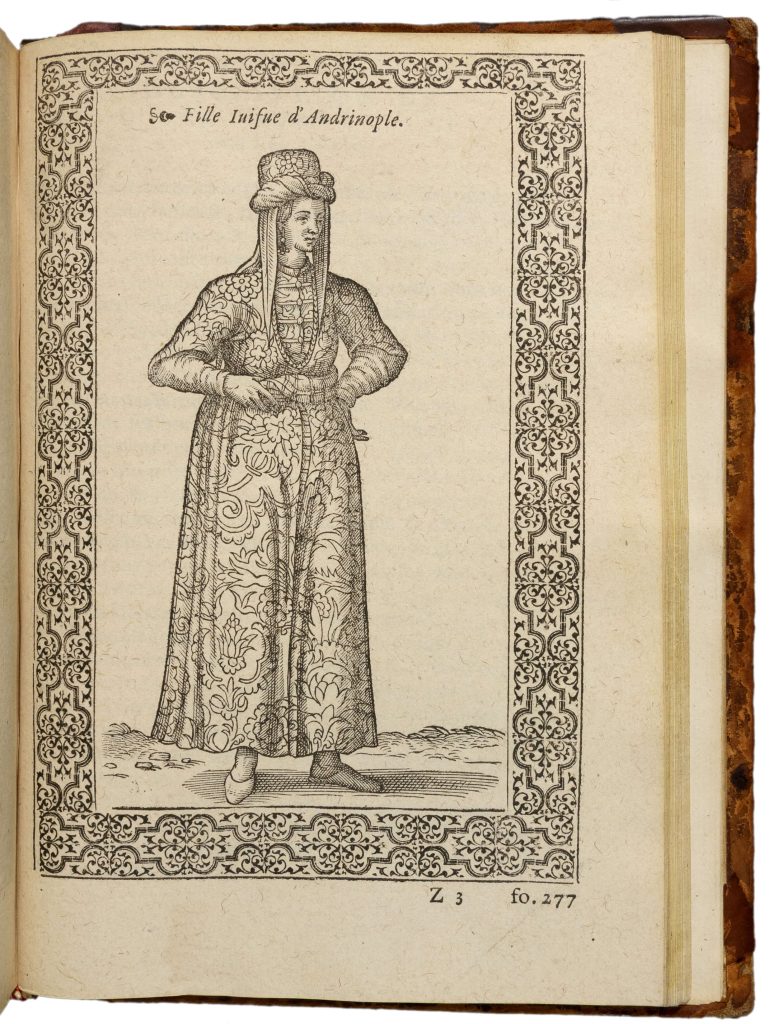

Nicolay pursues the strategic interplay of image and text to racialize Jews in his depictions of Levantine Jewish women. Their wardrobe, both modest and magnificent, make them nearly indistinguishable not only from Ottoman Muslim women, but from Christian women as well. However, this study in sartorial sameness incorporates identifying accessories[33] to materialize racial difference. Nicolay portrays the young Jewish woman of Andrinople wearing a distinctive cup-shaped hat and low-heeled shoes to convey her subordination, in contrast to Muslim women who don veils and high- or medium-heeled shoes to register their higher social status.[65] The shoe embodied the Muslim women’s superior social position by the verticality it produced, which physically lifted Muslim women while materially visualizing inferiority by lowering the stature of Jewish women. However, these same rulings apply to Christian women, represented in similar subordinating attire relative to Muslims. The threat that shared zimmi status posed to the Christian hierarchy over Jews reappears in this gendered context.

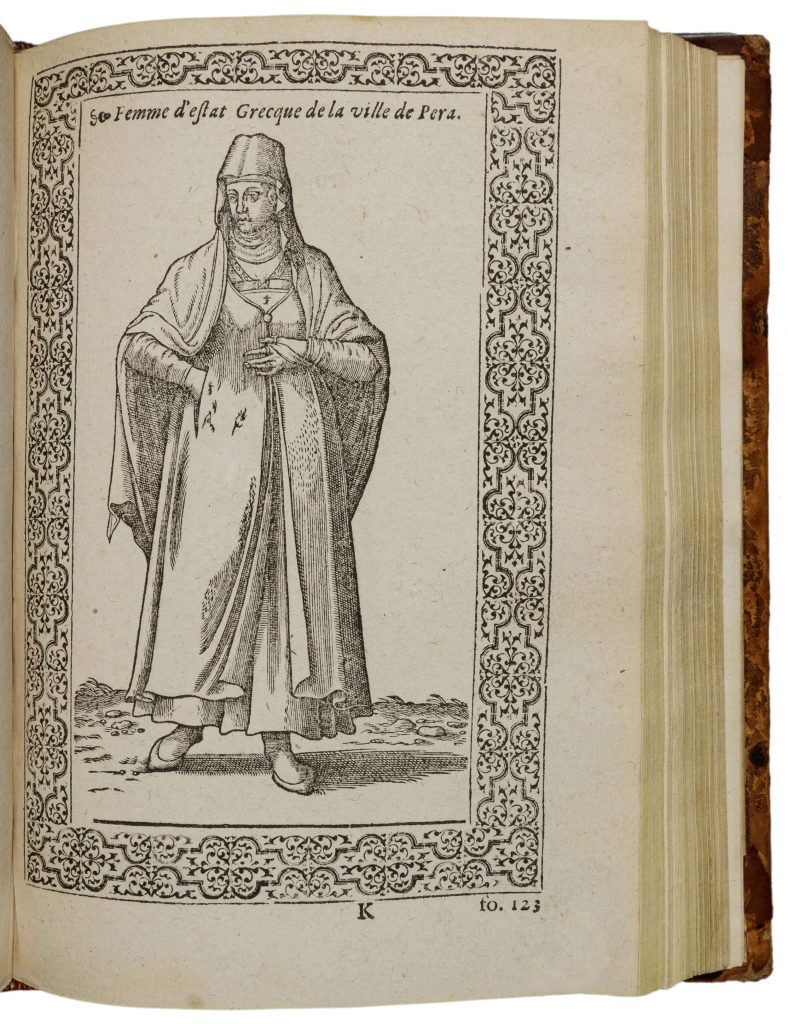

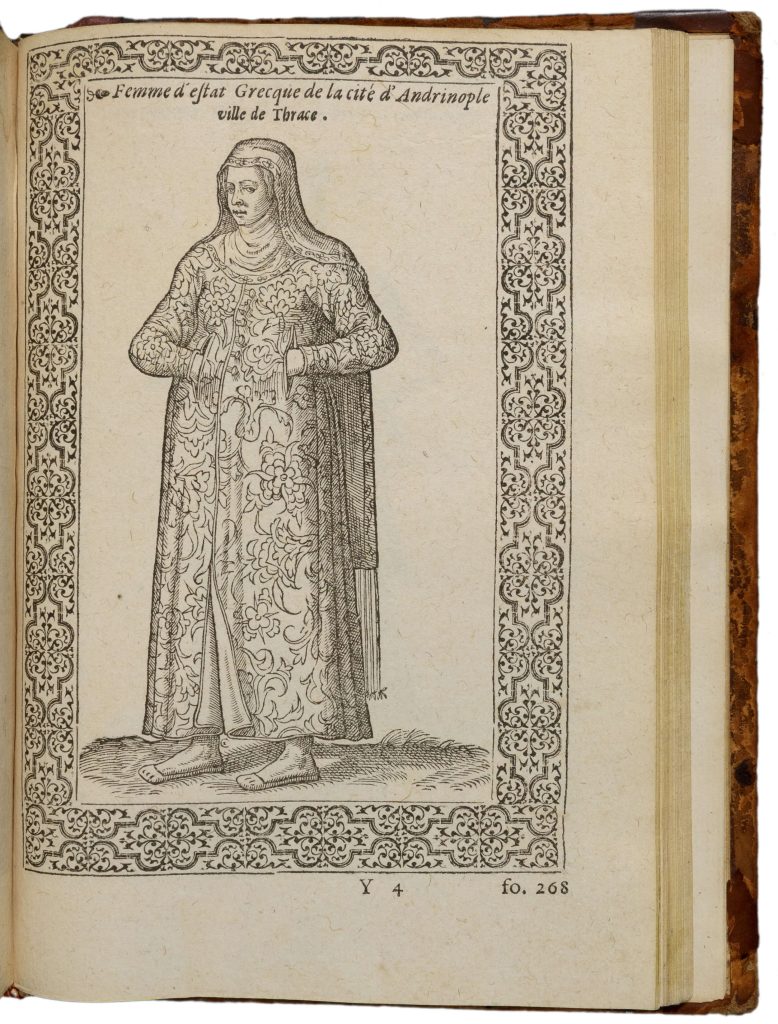

Furthermore, strategic portrayal of jewelry also suggests the problematic superiority of the wealth and adornments of Jewish women relative to Christian ones. Nicolay clads the older Jewish woman of Andrinople in a simple dress and wrap (Figure 2.4). The modesty of her garments, similar to a Christian gentlewoman of Pera, is offset and elevated by a prominent chain and pendant necklace worn low on her chest (Figure 2.5). Travelers observed that Levantine Jewish women, particularly Spanish émigrées, wore substantial pieces of jewelry, heirlooms given to daughters from their Sephardic mothers.[66] Her long chains mark her body with Jewish distinction, the simplicity of her dress further emphasizing the extravagance of her accessories. The adornment of the older Jewish woman’s attire is exceeded in the rendering of the young Jewish maiden (Figure 2.6). Nicolay presents the fictional fabric ornamenting the unmarried Jewish woman as a jacquard, probably damask velvet, and possibly brocaded, with flora patterning that exemplified the luxurious silk[35] garments of the international marketplace.[67] While this fabric also appears in the garment worn by the Christian gentlewoman of Andrinople (Figure 2.7), the young Jewish woman displays an additional long chain around her neck. The conspicuous consumption of sumptuous fabrics and expensive jewelry cladding the Jewish maiden’s body presents her with vestimentary prominence that competes with that of Christian women in Ottoman lands and threatens the supposedly inherent superiority of the latter.

Nicolas de Nicolay, “Jewish woman of Andrinople” (276r), Les navigations pérégrinations et voyages, faicts en la Turquie, Antwerp, 1576, Newberry Library, Wing ZP 5465 .S587

Nicolas de Nicolay, “Christian gentlewoman of Pera” (123r), Les navigations pérégrinations et voyages, faicts en la Turquie, Antwerp, 1576, Newberry Library, Wing ZP 5465 .S587

Nicolas de Nicolay, “Young Jewish woman of Andrinople” (277r), Les navigations pérégrinations et voyages, faicts en la Turquie, Antwerp, 1576, Newberry Library, Wing ZP 5465 .S587

Nicolas de Nicolay, “Christian gentlewoman of Andrinople” (268r), Les navigations pérégrinations et voyages, faicts en la Turquie, Antwerp, 1576, Newberry Library, Wing ZP 5465 .S587

Nicolay counters the doubled threat posed by both the indistinguishability and superiority of Jewish women’s apparel relative to that of neighboring Christians through strategic use of image and text. Nicolay offers visual and extensive verbal visions of the rich jewelry and apparel worn by other Christian women, such as those on the Ile of Chio, whose beauty he praises while depicting them wearing elaborate necklaces atop gowns and coats of sumptuous fabrics embroidered with gold and pearls.[68] Notably, he provides no textual exegesis related to the garments adorning his portrayals of two Jewish women from Andrinople; only captions identify their religion and their spatial coordinates. However, in the chapter describing the town and inhabitants of Andrinople, he describes a descending gradation in the accompanying illustrations: “As for the manner of the garments of the inhabitaunts, I haue hereafter presented in order the liuely drafts of a woman of estate of Graecia, of a Turky woman of [middle] estate, and of a mayden of ioy or a common woman, or strumpet.”[69] The order in which he presents these women begins with a Christian gentlewoman, then declines to a middle class Muslim woman, and finally, a sex worker. The images of the two Jewish women of Andrinople follow the woodcut of the sex worker, situating them at the nadir of the social structure, unworthy of even a mention in the text. If the similarity or superiority of attire threatens that of Christian women, the organizing syntax of the text along with the placement of images relegates Jewish women to their proper inferior place.

However, the Navigations considers Jewish women elsewhere in the text to reinforce the racial superiority enjoyed by Christian inhabitants of Ottoman lands relative to Jews. The allegation, advanced in medieval Christian discourses that Turks fulfil God’s will in punishing Jews with subordination, appears in the chapter on Jewish merchants.[70] The Jews are, Nicolay claims:

more persecuted of the Turkes, . . . then of any other nation, who haue them in such disdaine and hatred, that by no meanes they will eate in their companie, and much lesse marry any of their wiues or daughters, notwithstanding that oftentimes they doe marry with Christians, whom they permit too liue according to their lawe, and haue a pleasure too eate and bee conuersant with Christians: and that which is woorse, if a Iewe woulde become a Muselman, he should not bee receiued, except first leauing his Iudaical sect he became a christian.[71]

While universally hated, Jews, alleges Nicolay, suffer even more under Turkish persecution, a point emphasized in the marginal note in the original French text.[72] However, he falsely ascribes a rationale developed from Christian canon law, which forbids Christians to[37] eat and intermarry with Jews, to Muslim law, which in fact treats all zimmis as equals.[73] He also fabricates a hierarchy in which Christians enjoy privileges over Jews, asserting that Muslims willingly marry and share meals with the former but decline to do so with the latter out of contempt.[74] Here, he specifically alleges the inferiority of Jewish women in the estimation of Muslim men, who refuse to marry them. In contrast, Muslim men contract marriages with Christian women, holding them in esteem by allowing them to continue their religious observance. Nicolay nullifies the implicit threats to Christian hierarchy posed by the images of Jewish women, through either leveling similarity or superior ornamentation, in alleging their relative degradation by Muslims.

The conflicting evidence of image and word reveals the counterfactual labor of race construction, the effort that goes into bending empirical evidence of the Ottoman Jewish experience to fit the imperatives of Christian triumphalism. While Nicolay’s preface voices confidence in a glorious future of global Christianity, in contemporary Ottoman lands, the status of both Jews and Muslims often surpasses that of Christians, thwarting rather than fulfilling God’s will. The compensatory power of materialized degradation seeks to manifest the actual, essential status of infidel inferiority that Islamic law perniciously occludes.[75] In illustrating an ideality of Christian imperative, the Navigations aspires to transform the imperfect terrestrial world, permanently returning recalcitrant religious others to their proper subordinated place in the divine order.

- Kim F. Hall, Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995), 211–53. Ian Smith has recently advanced this field: “The Textile Black Body: Race and ‘Shadowed Livery’ in The Merchant of Venice,” in The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare and Embodiment: Gender, Sexuality, and Race, ed. Valerie Traub (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 170–85 and “Othello’s Black Handkerchief,” Shakespeare Quarterly 64, no. 1 (2013): 1–25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24778431 ↵

- This is the title of the first French edition (1567–68). We analyze the Newberry Library’s copy of Nicolas de Nicolay’s Les navigations et pérégrinations et voyages, faicts en la Turquie . . . (Antwerp: G. Silvius, 1576). The text follows the original French edition. Our discussion largely relies on the early modern English translation, The Nauigations, Peregrinations and Voyages, made into Turkie (London: Thomas Dawson, 1585), with occasional translations of our own to correct imprecise renderings in the early modern English text. ↵

- Joseph Hacker claims these are the earliest portrayals of Ottoman Jews, “The Sephardi Diaspora in Muslim Lands from the 16th to 18th Century,” in Odyssey of the Exiles: The Sephardi Jews 1492–1992, eds. Ruth Porter and Sarah Harel-Hoshen (Tel Aviv: Beth Hatefutsoth, Nahum Goldmann Museum of the Jewish Diaspora, 1992), 95–123, 201–4. ↵

- Some recent influential monographs on early modern critical race theory focusing on cultural constructions of race in the Christian West include Patricia Akhimie, Shakespeare and the Cultivation of Difference: Race and Conduct in the Early Modern World (New York: Routledge, 2018); Dennis Austin Britton, Becoming Christian: Race, Reformation, and Early Modern English Romance (New York: Fordham University Press, 2014); Geraldine Heng, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018); and Ania Loomba, “Race and the Possibilities of Comparative Critique,” New Literary History 40, no. 3 (2009): 501–22, https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.0.0103. ↵

- M. Lindsay Kaplan, Figuring Racism in Medieval Christianity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 4. ↵

- “As the only religious minority the Latin West knew and tolerated during the early Middle Ages, the Jews invariably presented Christendom with a paradigm for the evaluation and classification of the Muslim ‘other.’” Jeremy Cohen, Living Letters of the Law: Ideas of the Jew in Medieval Christianity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 161. For Cohen’s fuller discussion of Muslim-Jewish coordination, see Living Letters of the Law, 158–65, 219. See also Suzanne Conklin Akbari, Idols in the East: European Representations of Islam and the Orient, 1100–1450 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009). ↵

- In a thirteenth-century ruling, Pope Urban IV explicitly extends guilt for the crucifixion to Muslims: “these same Jews and Muslims, whose proper guilt submitted them to perpetual servitude” (our translation), in Solomon Grayzel and Kenneth R. Stow, The Church and the Jews in the XIIIth Century, Vol. 2 (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary in America, 1989), 79; and Kaplan, Figuring, chaps. 1 and 5. ↵

- David M. Freidenreich, “Muslims in Western Canon Law, 1000–1500,” in Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History, 5 vols., eds. David Thomas and Alex Mallett (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 3–42; and Kaplan, Figuring. ↵

- Kaplan, Figuring, 5; and Francisco Bethencourt, Racisms: From the Crusades to the Twentieth Century, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013), 7–8. ↵

- Phyllis G. Jestice, “A Great Jewish Conspiracy? Worsening Jewish-Christian Relations and the Destruction of the Holy Sepulcher,” in Christian Attitudes Toward the Jews in the Middle Age: A Casebook, ed. Michael Frassetto (New York: Routledge, 2007), 25, 27. ↵

- Jacques de Vitry, The History of Jerusalem. A.D. 1180, trans. Aubrey Stewart (London: Palestine Pilgrims’ Text Society, 1896), 87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10835-017-9266-0 ↵

- Jonathan Ray recently argues that sixteenth-century travel narratives gradually challenged medieval theological views. “Christian (Re)Encounters with Jews in the Sixteenth-Century Mediterranean,” Jewish History 30, no. 3/4 (2016): 183–206. However, his discussion (188–89) omits Nicolay’s theological condemnations of the Jews. ↵

- José Alberto Rodrigues da Silva Tavim, “The Grão-Turco and the Jews: Translation to the West of Two Oriental ‘Powers’ (XVI–XVII Centuries),” Mediterranean Historical Review 28, no. 2 (2013): 167–68, https://doi.org/10.1080/09518967.2013.837645. ↵

- Gilles Veinstein, “The Ottoman Jews: Between Distorted Realities and Legal Fictions,” Mediterranean Historical Review 25, no. 1 (2010): 54–55, https://doi.org/10.1080/09518967.2010.494100. ↵

- Tavim offers a synthesis of these apparently contradictory views, “Grão-Turco,” 181. ↵

- For the coordination of Muslim and Jewish women, see Louise Mirrer, Women, Jews, and Muslims in the Texts of Reconquest Castile (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996); and Britton, Becoming Christian. For the “fair” Saracen princess, see Jacqueline De Weever, Sheba’s Daughters: Whitening and Demonizing the Saracen Woman in Medieval French Epic (New York: Garland, 1998); and Sharon Kinoshita, “‘Pagans are wrong and Christians are right’: Alterity, Gender, and Nation in the Chanson de Roland,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31, no.1 (2001): 79–111, https://doi.org/10.1215/10829636-31-1-79. On Saracen whiteness in general, see Akbari, Idols. ↵

- Adrienne Williams Boyarin has recently argued for the derogating force of sameness, although she omits consideration of race: The Christian Jew and the Unmarked Jewess: The Polemics of Sameness in Medieval English Anti-Judaism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). ↵

- Ann Rosalind Jones and Peter Stallybrass, Renaissance Clothing, and the Materials of Memory (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 2. ↵

- Jones and Stallybrass, Renaissance Clothing, 5. Sumptuary laws offer another example of the social and economic force of clothing. Proscribing “clothing, fashions, fabrics, colors, and jewelry for societal groups in a way that corresponded to their levels on the social scale. . .sumptuary legislation thus functioned as an instrument to maintain and reinforce social barriers,” explains Maria Giuseppina Muzzarelli, “Reconciling the Privilege of a Few with the Common Good: Sumptuary Laws in Medieval and Early Modern Europe,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 39, no. 3 (2009): 599, https://doi.org/10.1215/10829636-2009-006. ↵

- Jones and Stallybrass, Renaissance Clothing, 11. ↵

- Valerie Traub, “Mapping the Global Body,” in Early Modern Visual Culture: Representation, Race, and Empire in Renaissance England, eds. Peter Erickson and Clark Hulse (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), 51. ↵

- See Bronwen Wilson, “Foggie diverse di vestire de’ Turchi: Turkish Costume Illustration and Cultural Translation,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 37, no. 1 (2007): 104, 134n18, https://doi.org/10.1215/10829636-2006-012. ↵

- Giorgio Riello, “The World in a Book: The Creation of the Global in Sixteenth-Century European Costume Books,” Past and Present 242, Supplement 14 (2019): 281–317, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtz047. ↵

- Quoted in Traub, “Mapping,” 51. ↵

- Margaret F. Rosenthal, “Cultures of Clothing in Later Medieval and Early Modern Europe,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 39, no. 3 (2009): 473, https://doi.org/10.1215/10829636-2009-001. ↵

- Heng argues that Canon 68 “instantiates racial regime, and racial governance, in the Latin West through the force of law” precisely through the regulation of clothing (Invention, 32). Muslim sartorial legislation designating the inferior status of minority religious groups perhaps influences medieval Christian law; see Ilse Lichtenstadter, “The Distinctive Dress of Non-Muslims in Islamic Countries,” Historia Judaica 5, no. 1 (1943): 35; Naomi Lubrich, “The Wandering Hat: Iterations of the Medieval Jewish Pointed Cap,” Jewish History 29, no. 3/4 (2015): 226, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10835-015-9250-5; and Flora Cassen, Marking the Jew in Renaissance Italy: Politics, Religion, and the Power of Symbols (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 45. Cassen’s analysis of the Jewish badge ultimately argues, wrongly in our view, against its racist force (194–98). ↵

- Solomon Grayzel, The Church and the Jews in the XIIIth Century, Rev. ed., Vol. 1 (New York: Hermon Press, 1966), 311. On the Christian designation of Muslims as pagans, see John Victor Tolan, Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 105–34. ↵

- Nicholas Vincent, “Two Papal Letters on the Wearing of the Jewish Badge, 1221 and 1229,” Jewish Historical Studies 34 (1994): 211; and Lubrich, “The Wandering Hat,” 226, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29779960. ↵

- John Teutonticus’ thirteenth-century commentary on the Lateran rulings indicates the canon’s intent to subordinate Jews and Muslims by citing other hierarchies effected through differentiated clothing (Vincent, “Two Papal,” 214). ↵

- Grayzel, Church, 1:308. ↵

- Grayzel, Church, 1:63–69. ↵

- Lubrich, “Wandering Hat,” 224. Sara Lipton argues for art’s power to create rather than reflect anti-Jewish attitudes in Dark Mirror: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Semitic Iconography (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2014), 10; she devotes a chapter to the early history of the “Jewish hat” (13–54). ↵

- Debra Strickland analyzes the tortil as one such identifying headwear, Saracens, Demons and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003), 161, 174, 177, 181. ↵

- Strickland explains that this portrayal sometimes appears in images establishing both Muslims and Jews as idolaters, Saracens, 106, 137, 157–68. Depictions of turbans that connected and racialized Muslims and Jews in early modern images, such as in Pierre Boiastuau’s Histoires prodigieuses (1560), continued associations with idolatry and violence against Christians. ↵

- Diane Owen Hughes, “Distinguishing Signs: Ear-Rings, Jews and Franciscan Rhetoric in the Italian Renaissance City,” Past & Present 112 (1986): 6, 10–11, http://www.jstor.org/stable/650997. ↵

- Scholars attesting to the impact of Nicolay’s images include David Brafman, “Facing East: The Western View of Islam in Nicolas de Nicolay’s ‘Travels in Turkey,’” Getty Research Journal 1 (2009): 154, https://doi.org/10.1086/grj.1.23005372; Marie-Christine Gomez-Géraud and Stefanos Yerasimos, Dans l’empire de Soliman le Magnifique (Paris: Presses du CNRS, 1989), 33–36; Frédéric Hitzel, “Les ambassades occidentales à Constantinople et la diffusion d’une certaine image de l’Orient,” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 154e année, 1 (2010): 279, https://doi.org/10.3406/crai.2010.92806; Chandra Mukerji, “Costume and Character in the Ottoman Empire: Dress as Social Agent in Nicolay’s Navigations,” in Early Modern Things: Objects and Their Histories, 1500–1800, ed. Paula Findlen (London: Routledge, 2013), 151; Wilson, “Foggie diverse,” 110; and Amanda Wunder, “Western Travelers, Eastern Antiquities, and the Image of the Turk in Early Modern Europe,” Journal of Early Modern History 7, no. 1/2 (2003): 119, https://doi.org/10.1163/157006503322487368. Gomez-Géraud and Yerasimos, Dans l’empire, list ten early modern editions of the Navigations: three French, two German translations, one English translation, one Dutch translation, and three Italian translations (33). Wilson explains that Nicolay’s “figures became archetypes, and their poses and attire were replicated, even traced, in at least eight costume books that were published by 1601” (“Foggie diverse,” 110). Mukerji argues that the multiple translations indicate “printers clearly assumed people wanted to read it as well as look at the pictures. So the text as well as the illustrations mattered” (“Costume,” 166). ↵

- This embassy sought to forge a French alliance with the Ottoman Porte against the Holy Roman Empire; Nicolay’s ambivalent view of the “Turk” resonates with that of contemporary French authors, Marcus Keller “Nicolas de Nicolay’s ‘Navigations’ and the Domestic Politics of Travel Writing,” L’Esprit Créateur 48, no. 1 (2008): 18–31, https://doi.org10.1353/esp.2008.0005, and “The Turk of Early Modern France,” L’Esprit Créateur, 53, no. 4 (2013): 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1353/esp.2013.0045. Radu G. Păun demonstrates the extent of Nicolay’s borrowing: “Sur quelques ‘modèles’ livresques: les ‘Navigations et pérégrinations’ de Nicolas de Nicolay,” Revue des études sud-est européennes 33, no. 1/2 (1995): 171–80. However, Nicolay included some copies of other artists’ work alongside his original images (Wilson, “Foggie diverse,” 114). ↵

- Wunder notes the relationship between word and image: “The combination of images and the verbal explanations created a multi-layered ekphrasis that brought to life the peoples of the Levant for the reader/viewer of the Navigations.” “Western Travelers,” 117. See also Mukerji, “Costume and Character,” 156; Wilson, “Foggie diverse,” 110; Păun, “Sur quelques ‘modeles,’” 173; and Brafman “Facing East,” 153. ↵

- Keller, “Nicolas,” 22. The preface, absent in the English edition, imagines all humans mutually emending their barbarous vices and equally instructing themselves in “the true religion,” forging a community of whom God is the great father and Jesus Christ the oldest son, Navigations (1576), NP, fourth page of Preface. ↵

- Zimmi is the Turkish form of dhimmî, a member of ahl al-kitâb, “people of the Book,” that included Jews and Christians to whom Islam accorded religious toleration and protection at the price of social and political inferiority. Restrictions on the zimmi included payment of a poll tax and wearing distinguishing garments as an “enforced sign of inferiority to the ruling class,” Lichtenstadter, “Distinctive Dress,” 38, 44. See also Minna Rozen, A History of the Jewish Community in Istanbul: The Formative Years, 1453–1566 (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 16–17. ↵

- Păun, in reviewing the common topoi Nicolay repeats from other authors, registers surprise over the avoidance of the well-represented observation that Ottoman Jews own Christian slaves (“Sur quelques ‘modèles,’” 175). Given Nicolay’s aim to demonstrate Christian superiority over Jews in the Ottoman context, we might assume a deliberate suppression of this [pb_glossary id="263"]topos[/pb_glossary]. ↵

- Léon Davent executed sixty copperplate engravings for the original French edition (1567–68) from drawings Nicolay made during his travels in the Levant. In 1576, Willem Silvius published a second French edition of Nicolay’s book in Antwerp, as well as translations in Dutch, German, and Italian, with woodcuts by Anton van Leest copied from Davent’s engravings. See David Brafman, “Les quatre premiers livres des navigations et pérégrinations Orientales,” in Christian-Muslim Relations 1500–1900, ed. David Thomas, http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2451-9537_cmrii_COM_26242. ↵

- Some hand-colored volumes of the first edition appear to have been produced, copies of which are held in the Victoria and Albert Museum (https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1463611/les-quatre-premiers-livres-des-book-nicolas-de-nicolay/) and the British Library (Wilson, “Foggie diverse,” 110). On religious identity and garment color, see Rozen, History, 284. ↵

- Wunder considers Nicolay’s use of color in his text to supplement his images: “The author was surprisingly silent about pigmentation and physiology, channeling his energy instead into detailed descriptions of costumes. The print portraits in the book directly communicated what Nicolay had seen abroad, down to the finest details, while the text revealed that which the black-and-white linear images could not communicate (colors, fabrics, and explanations for peculiarities of dress)” (“Western Travelers,” 116–17). Wilson observes, “Although Nicolay often describes the colors of the costumes in the text, extant hand-colored editions indicate that illuminators did not read the text or were not interested in accuracy” (“Foggie diverse,” 110). Kaplan disagrees after consulting the British Library hand-colored 1568 edition (Shelf mark C.18.c.8.); the colors indicated in the text match the coloring of the hat and turban worn by the Jewish physician and merchant respectively. However, the colorist did use shades of gray wash to indicate dark skin on a number of figures, including several images of “Moors.” ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 93r. ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 93r. Early seventeen-century Ottoman records of physicians affirm Jews outnumbering Muslims (Rozen, History, 208–9). ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1576), 169, our translation. Lale Uluç cites other early modern travel narratives mentioning the yellow turban, “Images of Jews in Ottoman Court Manuscripts,” in A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations: From the Origins to the Present Day, eds. Abdelwahab Meddeb and Benjamin Stora (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013), 903. ↵

- Lichtenstadter cautions against approaching Muslim clothing legislation “from an exclusively Jewish angle, for it arose out of the relationship prevailing generally between Muslims and all non-Muslims, whether Christian, Jewish, or of any other non-Muslim faith” (“Distinctive Dress,” 35). ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 131v. ↵

- Concerns about indistinguishability fanned fears that converted Jewish physicians in Iberia could hide behind an orthodox appearance while secretly murdering Christians. François Soyer argues that Jewish anti-Christian medical conspiracies inspired charges against Muslim converts, “Antisemitism, Islamophobia and the Conspiracy Theory of Medical Murder in Early Modern Spain and Portugal,” in Antisemitism and Islamophobia in Europe: A Shared Story?, eds. James Renton and Ben Gidley (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 51–75, 58, 66. See Tavim, “Grão-Turco,” 173–76. ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 130v–131r. ↵

- Veinstein proves the fallacy of this accusation; the Turkish innovation in weaponry stemmed from information provided by French army deserters in the late 1490s, “Ottoman Jews,” 55. See also Tavim, “Grão-Turco,” 176–79. ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 131r. ↵

- In early modern French, tribut signifies a contribution imposed by a nation on another, vanquished people; the first definition of tributaire, a person or people owing tribute, is the Jews. See Adolphe Hatzfeld, et al., Dictionnaire général de la langue Française (Paris: Librairie Charles Delagrave, 1926). ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 133v. Lichtenstadter discusses the poll tax, “The Distinctive Dress,” 38–39. Nicolay frequently mentions Christian payment of tribute, both in money and through enslavement, Navigations (1585), 36v–37v, 45r–45v, 69rff, 95r, 128r, and 160r. ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 149v. ↵

- Rozen, History, 287. ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 131v–132r. ↵

- Nicolay claims Jews “haue. . .the moste. . .trafique of merchandize and readie money. . . in al Leuant” (Navigations, 130v). Nicolay mostly toured Galata, a predominately Jewish area with many warehouses, giving him “the impression that most of the commerce was controlled by Jews” (Rozen, History, 239). ↵

- Rozen, History, 233–34. ↵

- Fynes Morrison’s early modern travel narrative (1617) mentions the Christian limitation of Jewish economic activity to lending clothes and money; see Charles Hughes, ed., Shakespeare’s Europe: A Survey of the Condition of Europe at the End of the 16th Century, 2d ed., (New York: B. Blom, 1967), 487–88. For Jews in the second-hand clothes trade, see Patricia Allerston, “Reconstructing the Second-Hand Clothes Trades in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Venice,” Costume 33, no. 1 (1999): 46–56, https://doi.org/10.1179/cos.1999.33.1.46; and Kate Kelsey Staples, “The Significance of the Secondhand Trade in Europe, 1200–1600,” History Compass 13, no. 6 (2015): 297–309, https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12240. ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 130v–131r. Canon law condemns a Jewish creditor’s exercising power over a Christian debtor (Grayzel, Church, 1:307). Jones and Stallybrass discuss the association of pawnbroking, second-hand clothes, and usury (Renaissance Clothing, 181–82). ↵

- Ulinka Rublack argues that Bertelli’s Paduan peddler references the racial trope of greedy Jewish usurers in Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 221. ↵

- Jews in Istanbul were not primarily itinerant peddlers: “The most common role for a Jew in Istanbul’s commercial sector was that of a small shopkeeper” (Rozen, History, 233–34). ↵

- As Rozen explains, “several items of apparel differentiated between zimmi and Muslim women; . . . high heels and the veil, were probably worn to emphasize that the Muslims were of a higher class” (History, 287). ↵

- Mark Mazower, Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews, 1430–1950 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 54–55; and Peter Christensen, “‘As If She Were Jerusalem’: Placemaking in Sephardic Salonica,” Muqarnas 30, no. 1 (2013): 168n41, https://doi.org/10.1163/22118993-0301P0007a. ↵

- On the Jewish maiden, see Christensen, “‘As If She Were Jerusalem,’” 148. On pictorial representations of luxurious textiles, see Rembrandt Duits, Gold Brocade and Renaissance Painting: A Study in Material Culture (London: Pindar Press, 2008). ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 37r–39r; see especially the portrayal of the young woman of the island of Chio in Navigations (1576), 72r. Nicolay depicts Chios as an exemplary Christian polity within the Ottoman context, (Keller, “Nicolas,” 25). Păun identifies the beauty of the women of Chios as another topos common among French authors (“Sur quelques ‘modèles,’” 172). ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 141r, emphasis added. The English edition incorrectly translates the French “moyen estate” as “mean” or low status. ↵

- See claims by Jacques de Vitry discussed earlier and Tavim, “Grão-Turco,” 179–81. ↵

- Nicolay, Navigations (1585), 131r–v. ↵

- “Jews hated by all nations and especially by Turks” and “A Christian woman married to a Turk is permitted to live according to her law, [i.e., continue to practice Christianity],” our translation. Nicolay, Navigations (1576), 247. ↵

- David M. Freidenreich, “Jews, Pagans, and Heretics in Early Medieval Canon Law,” in Jews in Early Christian Law: Byzantium and the Latin West, 6th–11th Centuries, eds. John V. Tolan et. al (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2014), 73–91, especially 76–79. “Christian authorities . . ., unlike Muslims, found it important to establish laws directed exclusively at Jews” (91). ↵

- The canard that Muslims prohibit Jews from converting to Islam unless they first become Christian circulates through other early modern texts written by Christians, Ania Loomba and Jonathan Burton, Race in Early Modern England: A Documentary Companion (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 172, 196. ↵

- For an example of somatic, rather than material, manifestation of inherent Jewish inferiority, see Kaplan, Figuring, 81–102. ↵

relative to the body

in the manner of a metonymy, a figure of speech that consists in mentioning a thing for another thing with which it is somehow associated

relative to the Christian Church Fathers or their writings

religious rule approved by the Catholic Pope

bound to replace something else

ecclesiastical council of the Catholic Church held in Rome in the Lateran Palace next to the Lateran Basilica in order to rule on questions of doctrine

relative to clothing

itinerant salesman who sells small items in the street or door to door

person who emigrated, leaving their homeland

refers to the Jewish and Jewish-descended people expelled from Spain and Portugal in the late fifteenth century, and by extension to Mediterranean Jewish culture

fabric with intricate patterns woven into it (as opposed to printed or embroidered)

jacquard whose patterns are woven in satin into a different material

silk fabric with raised patterns in gold and silver

opposite of the zenith, lowest point of something