Exhibition Catalog

Part 3. Performing

[Print edition page number: 190]

Case Study #1: Literary Drama

Entry #27

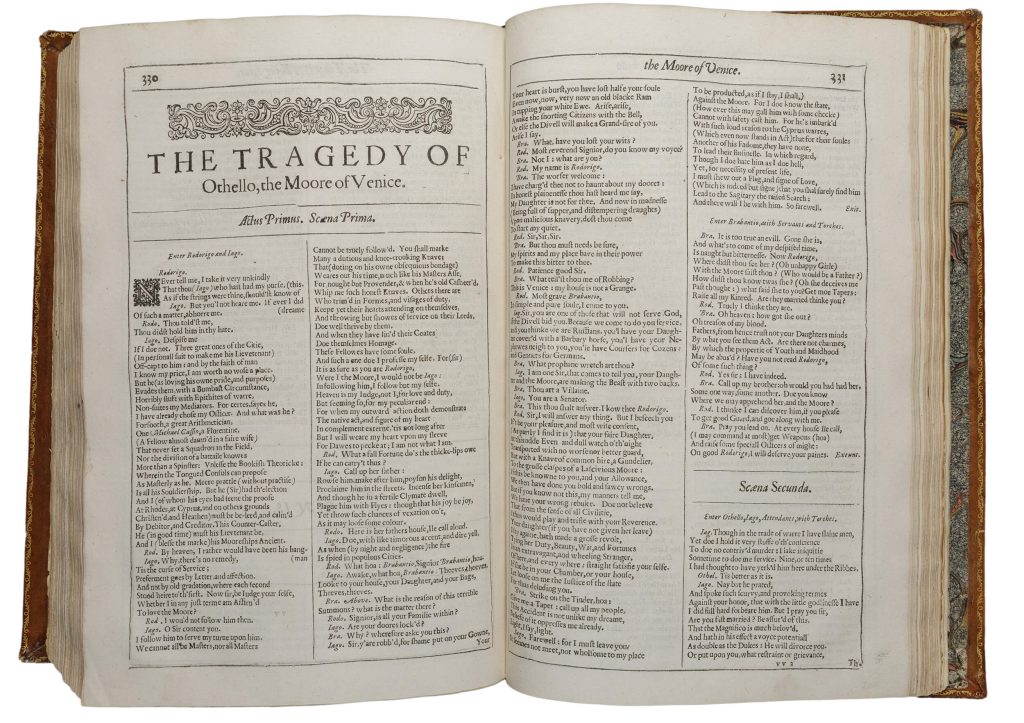

William Shakespeare (1564–1616)

“The Tragedy of Othello, the Moore of Venice” in Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, and tragedies: published according to the true originall copies, 1632

Book with letterpress, engraving, and woodcuts

Case folio YS .02

Shakespeare’s Othello (1604) constitutes the most well-known representation of Blackness on the early modern English stage: the play famously follows the trajectory of Othello, a “Moor” and general in service to Venice, and his doomed marriage to Desdemona. The plot is partially derived from a novella by the Italian writer Giovanni Battista Giraldi, also known as Cinthio (1504–1573). The play text, particularly in the speech of Othello who details a personal history that includes a period of enslavement, incorporates language reminiscent of popular early modern travelogues; such travel writings blend personal narrative with fantastical accounts of an exoticized world outside England. Othello is often read and taught side by side with the Moorish characters of Vecellio’s 1590s costume book De gli habiti antichi et moderni di diversi parti del mondo (Cat. No. 8).

Othello was performed widely in the seventeenth century and in a range of settings, including the Stuart Court and the Globe Theatre. Little is known as to the specific[191] mechanics of its early modern staging of Blackness, but we know that, generally, Blackamoor characters were performed in black-up in early modern English performance culture. The play’s popularity and extensive performance history position Othello as an enduring race-making object. The play constructs its own self-defined category of “Moor,” reinforces medieval and early modern associations of Blackness with the devil, and sensationalizes interracial relationships as inherently dangerous to white femininity for centuries of productions to follow.

Further Readings

Akhimie, Patricia. “Othello, Blackness, and the Process of Marking X.” Chap. 1 in Shakespeare and the Cultivation of Difference: Race and Conduct in the Early Modern World. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Smith, Ian. “White Skin, Black Masks: Racial Cross-Dressing on the Early Modern Stage.” Renaissance Drama 32 (2003): 33–67. https://doi.org/10.1086/rd.32.41917375.

Thompson, Ayanna. “Introduction.” In Othello. By William Shakespeare. Edited by E.A.J. Honigmann, 1–116. New York:

Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016. [192]

Beatrice Bradley

Entry #28

Thomas Rymer (1641–1713)

A short view of tragedy it’s original, excellency and corruption: with some reflections on Shakespear and other practitioners for the stage, 1693

Book with letterpress

Case Y 0278 .77

(no image)

Thomas Rymer’s scholarly work A short view of tragedy (1693) glosses over the literary history of tragedy on the European stage, tracing the genre’s successes and failures from ancient Greece to seventeenth century England. Embracing neoclassical views, Rymer believes a tragedy is made up of four essential parts: the fable, the characters, the rhetoric, and the expression. By mobilizing these elements, a tragedy distills the essence of beauty and humanity into literary knowledge that transcends superficial sensory pleasure. Rymer criticizes contemporaries such as Shakespeare on the basis that his plays are “bloody farces” that betray the tragic tradition. Yet, in pointing out contemporary tragedies’ deviations from the classical model, he also inadvertently reveals how literary productions are indeed rooted in changing social circumstances. The book’s struggle to reconcile tragedy’s essence with its history is best reflected in the chapter on Othello, as Rymer projects his anxieties onto analyses of Shakespeare’s Black general.

Rymer argues that Othello is a fable with unconvincing characters that lacks relevance to life. Desdemona defies the expectations attached to aristocratic daughters, while Iago is nothing like a virtuous soldier. Othello’s credibility is questioned on the basis of his identity: Rymer does not find it probable that a Black character could possess a name, a reputation, let alone gain trust from Venetians to be a general. Blackness is posited as an essence that cannot be transcended at the very end of the seventeenth century. Rymer’s neoclassical dismissal of the play’s verisimilitude ironically mirrors the prejudices that Othello experiences in the play.

Further Readings

Cacicedo, Alberto. “Othello, Stranger in a Strange Land.” Interdisciplinary Literary Studies 18, no. 1 (2016): 7–27. https://doi.org/10.5325/intelitestud.18.1.0007.

Cannan, Paul D. “‘A Short View of Tragedy’ and Rymer’s Proposals for Regulating the English Stage.” The Review of English Studies 52, no. 206 (2001): 207–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/res/52.206.207.

Nicholson, Catherine. “‘Othello’ and the Geography of Persuasion.” English Literary Renaissance 40, no. 1 (2010): 56–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6757.2009.01061.x.

Vivian Lei

Entry #29

Jean-François Ducis (1733–1816)

Othello, ou, Le more de Venise: Tragédie

Book with letterpress, 1794

FRC 17779

(no image)

Jean-François Ducis’s adaptation of Othello premiered at the Théâtre de la République in November 1792, at the height of French Revolution fever. Ducis had previously adapted several Shakespearean plays, but with superstar François-Joseph Talma as lead, Othello would be his greatest success. In the “avertissement” (warning), Ducis warns the reader that he had Talma use bronzeface instead of the blackface in vogue on[193] English stages in order not to “revolt the ladies’ eyes” and to let the actor use facial expressions more effectively. Arguing that the most brutal aspects of Shakespeare’s play could not please “le caractère de la nation française” (the character of the French nation), Ducis published the play with two alternative endings: in the happy version, allies stop Othello from murdering Desdemona in the nick of time.

Both versions, however, emphasize the role of General Othello as the precious instrument of a State whose Frenchness is palpable in its pervasive revolutionary language. The happy version ends with Othello stating: “Should rebels trouble the Republic / And tear her down, let me save it / Or die trying.” The prolonged opposition of Desdemona’s father to her wedding leads him to conspire against the State itself, construing racism as a political crime of grave import. It may not be a coincidence that Ducis dedicated his Othello to his brother in Saint-Domingue, about half a year after the National Assembly granted political and civil rights to free men of color as a compromise following the start of the Haitian Revolution. At the time, abolitionist plays flourished in Paris.

Further Readings

Carlson, Marvin, trans. Shakespeare Made French: Four Plays by Jean-François Ducis. New York: Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Publications, 2013.

Chalaye, Sylvie. Du Noir au Nègre: L’image du Noir au théâtre (1550–1960). Paris: L’Harmattan, 1998.

Monaco, Marion. Shakespeare On the French Stage in the Eighteenth Century. Paris: Didier, 1974.

Noémie Ndiaye

Entry #30

Aphra Behn (1640–1689)

Oroonoko, or The Royal Slave (1688), in The histories and novels of the late ingenious Mrs Behn: in one volume. Viz. Oroonoko, or The royal slave. . . etc, 1696

Book with letterpress

Case 3A 483

(no image)

Aphra Behn’s 1688 novella, Oroonoko, was reprinted in this posthumous 1696 collection of her works in prose. The title page draws attention to Behn’s career-long experimentation with narrative form, as “Histories and Novels” is printed in the largest font on the page. Oroonoko is the lead title of this collection, which is fitting as Oroonoko is often considered one of the first novels written in the English language. The narrative follows the life of African aristocrats Imoinda and Oroonoko. The story recounts their romance in Coramantien and their separate capture and enslavement by white traders operating in colonial Surinam. In Surinam, Imoinda and Oroonoko are reunited and initiate a slave rebellion that leads to their deaths.

Oroonoko’s form and ethics are indeterminate: Is this an early novel? Is this proto-abolitionist fiction? Narrative ambiguity is a hallmark of the novel form — from the unreliable narrator, to the irrepresentability of the spectacular scene of dismemberment befalling the protagonist, to the tenuous relationship between reality and fiction. These novelistic elements produce a complex representation of early plantation relationships between race and gender, properties and persons, enslavement and freedom. While Behn’s female narrator appears sympathetic to Oroonoko and Imoinda’s plight, her inaction upon their rebellion’s dissolution demonstrates the fraught bonds between colonial white women and enslaved Black persons. In doing so, the novel lays bare the complicity of white sentimentality within structures of colonialism and slavery. Behn’s passive gaze on Oroonoko’s gruesome end parallels the passive white gaze of her novel’s audience.[194]

Further Readings

Anderson, Emily Hodgson. “Novelty in Novels: A Look at What’s New in Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko.” Studies in the Novel 39, no. 1 (2007): 1–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29533796.

Ellis, Markman. “‘The house of bondage’: Sentimentalism and the Problem of Slavery.” Chap. 2 in The Politics of Sensibility: Race, Gender, and Commerce in the Sentimental Novel. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Ferguson, Margaret W. “Juggling the Categories of Race, Class and Gender: Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko.” In Troping Oroonoko from Behn to Bandele, edited by Susan B. Iwanisziw, 16–34. London: Routledge, 2018.

Sarah-Gray Lesley

Entry #31

Thomas Southerne (1660–1746), author; Based on the novel by Aphra Behn (1640–1689)

Oroonoko: a tragedy as it is acted at the Theatre-Royal, by His Majesty’s servants, 1696

Book with letterpress

Case Y 135 .S7269

(no image)

The title page of Thomas Southerne’s 1696 play, Oroonoko, occludes that it is an adaptation of Aphra Behn’s 1688 novel by the same name. This omission is prophetic for Oroonoko’s eighteenth-century reception history: Southerne’s play (first performed in 1695) is referenced far more often than the original in later adaptations. The differences between Southerne’s play and Behn’s novel reveal what later audiences preferred. Southerne’s play is entirely set in Surinam, omitting Imoinda and Oroonoko’s love story in Coramantien, which is central to Behn’s novel. He replaces it with a romantic-comedy subplot for new characters — the white Welldon sisters. His most striking change, however, is his choice to whiten Imoinda, who is Black in Behn’s novel. It is this version of Imoinda that survives into the eighteenth century.

In whitening Imoinda, Southerne puts his story in dialogue with another famous seventeenth-century play featuring a Black protagonist — William Shakespeare’s Othello (1604). In both Behn’s and Southerne’s versions, Imoinda dies willingly by her husband’s hand, but Southerne’s staging of a white woman’s death at the will of her Black husband uniquely evokes Desdemona’s fate in Othello. Southerne thus dramatizes, exaggerates, and tropes the white racial fantasy of the passive white woman and the violent Black man. Made canon by Shakespeare, this fantasy is translated here onto the early plantation setting. In obscuring Behn’s place as source author, adding a white romantic-comedy subplot, and whitening Imoinda, Southerne’s Oroonoko anchors its conception of race in fantasies of white femininity.

Further Readings

MacDonald, Joyce Green. “Race, Women, and the Sentimental in Thomas Southerne’s Oroonoko.” Criticism 40, no. 4 (1998): 555–70. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23124316.

——— . “The Disappearing African Woman: Imoinda in Oroonoko after Behn.” Chap. 4 in Women and Race in Early Modern Texts. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Rosenthal, Laura J. “Owning Oroonoko: Behn, Southerne, and the Contingencies of Property.” Renaissance Drama 23 (1992): 25–58. https://doi.org/10.1086/rd.23.41917283.[195]

Sarah-Gray Lesley

Entry #32

William Shakespeare (1564–1616)

The most lamentable tragedie of Titus Andronicus. As it hath sundry times beene plaide by the Kings maiesties seruants, 1611

Book with letterpress

VAULT Case 3A 888

(no image)

William Shakespeare’s first tragedy Titus Andronicus (1591) orchestrates a revenge plot full of graphic violence and deep-seated racial anxieties. Although the play was long seen as one of Shakespeare’s less polished works, it was extremely popular on the early modern English stage. Following general Titus Andronicus’ return to Rome with a group of Gothic prisoners, the play’s plot unfolds as the imprisoned Gothic queen schemes her revenge against Titus with her black-skinned “Moorish” lover Aaron. The play’s gruesome poetics situate flesh as the ground for racial and cultural conceptualizations.

Aaron’s flesh is marked differently by his skin color and subaltern status, resonating with the image of Spanish runaway slaves (cimarrónes) in sixteenth-century Europe. Aaron’s “fleshiness” is also metaphorized through the play’s characterization of him as someone “barbarous,” licentious, and driven by physical passion. Yet, Aaron’s trickster quality is so overpowering that his words, replete with literary allusions to the humanistic tradition, become a weapon that indirectly kills many of the characters in the play, turning them into bloody corpses: literal flesh whose identity can no longer be located in a bounded, normative, and cultivated body. Racial boundaries are erased as the audience becomes unable to differentiate the flesh of the Moor from his allegedly more rational and “civilized” white counterparts. Ultimately, the soon-to-be emperor of Rome, Lucius, further blurs the lines by acting as a Barbarian when he feeds Tamora’s corpse to beasts, standing in opposition to the values of law, justice, and civility that are often deemed central to the Roman (and to Shakespeare’s) culture.

Further Readings

Ndiaye, Noémie. “Aaron’s Roots: Spaniards, Englishmen, and Blackamoors in Titus Andronicus.” Early Theatre: A Journal Associated with the Records of Early English Drama 19, no. 2 (2016): 59–80. https://doi.org/10.12745/et.19.2.2847.

Sale, Carolyn. “Black Aeneas: Race, English Literary History, and the ‘Barbarous’ Poetics of Titus Andronicus.” Shakespeare Quarterly 62, no. 1 (2011): 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1353/shq.2011.0001.

Willis, Deborah. “The Gnawing Vulture: Revenge, Trauma Theory, and Titus Andronicus.” Shakespeare Quarterly 53, no. 1 (2002): 21–52. https://doi.org/10.1353/shq.2002.0017.[196]

Vivian Lei

Entry #33

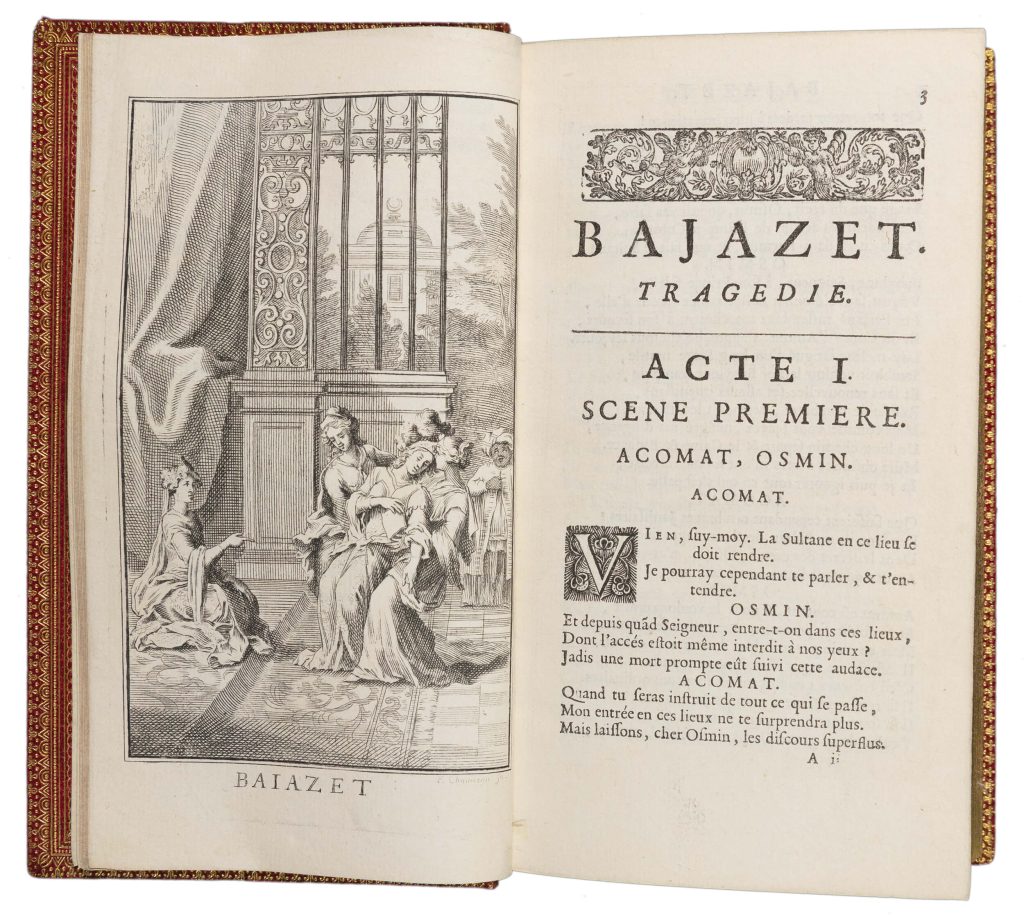

François Chauveau (1613–1676), engraver

Frontispiece of Bajazet, in Oeuvres de Racine, Tome II

Book with engravings, 1697

PQ1885 1697

This 1697 edition of Jean Racine’s plays copies the engravings that François Chauveau had produced for the original collected edition of 1676. The frontispiece of Bajazet (1672) represents Act IV scene 3, when Sultana Roxane shares with a fainting Atalide the letter she received, in which Sultan Murad IV demands that she execute his brother Bayazid, whom Roxane and Atalide both love. The curtain and the view onto the garden of the seraglio, which looks like one of the painted screens used in baroque scenography, form a theatrical décor for this Orientalist scene. Notice the Black character in Turkish habit upstage left. The juxtaposition between this Black eunuch and the cluster of white women (their outfits touch) draws on the popular trend in late- seventeenth-century portraiture to represent aristocratic women with a Black page as a visual strategy constructing their whiteness.

In the play, this character is Orcan, a high-ranking enslaved African, who has just delivered the Sultan’s letter, and whose secret mission is to murder Roxane. The play’s resolution hinges on Orcan, yet he never appears on stage. Chauveau, who is notorious for engraving moments not represented on stage, perceived the importance of Orcan, and captured his invisibilization. Indeed, the particular placement of Orcan in the crease of this tiny book (6.5 × 5.5 inches), which the reader will not fully open for fear of breaking the binding, puts him at risk of literal disappearance in the pages of history, and highlights the attention needed to see Blackness in neoclassical French archives.

Further Readings

Hall, Kim F. “‘An Object in the Midst of Other Objects’: Race, Gender, Material Culture.” Chap. 5 in Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995.

Ndiaye, Noémie. “Blackspeak: Acoustic Blackness and the Accents of Race.” Chap. 3 in Scripts of Blackness: Early Modern Performance Culture and the Making of Race. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022.

Picard, Raymond. “Racine and Chauveau.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 14, no. 3/4 (1951): 259–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/750342.[198]

Noémie Ndiaye

Entry #34

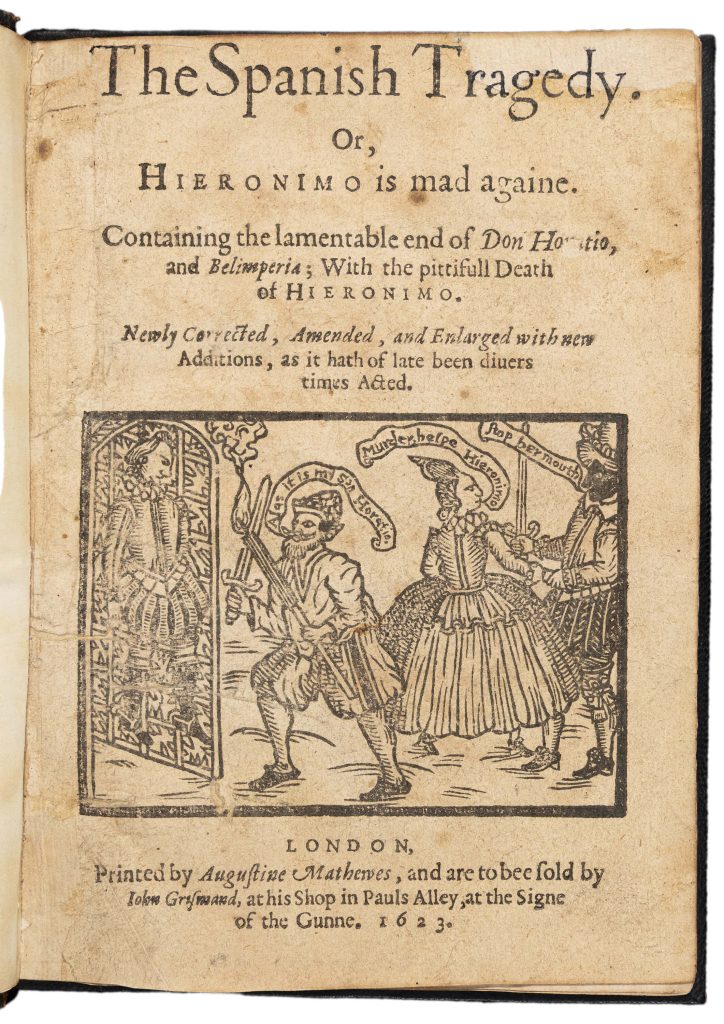

Thomas Kyd (1558 – 1594), author (published anonymously)

The Spanish tragedy, or Hieronimo is mad againe: containing the lamentable end of Don Horatio and Belimperia, with the pittiful death of Hieronimo (also known as Hieronimo is mad againe), 1623

Book with letterpress and woodcuts

Case Y 135 .K984

A woodcut appears on the title page of Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy in four editions from 1615 to 1633, including the 1623 edition. To the right, Bel-Imperia attempts to fight off abduction by her brother Lorenzo in Act 2. The play text describes Lorenzo as accompanied by multiple men and “disguised” (D2r) — an apparently ineffective disguise, as Bel-Imperia immediately recognizes her kidnappers — but Lorenzo in the woodcut is depicted alone and in blackface. The image suggests that the actor’s so-called disguise involved either cosmetic makeup or, perhaps more likely, a mask. As represented in the woodcut, Lorenzo’s hands are white, with one gripping his sister and the other a sword. Banderoles (speech ribbons) are attached to the figures of Hieronimo, Bel-Imperia, and Lorenzo, featuring condensed speech from the play.

Lorenzo’s appearance in blackface underscores early modern associations of Blackness with wickedness, but it also points to the complicated representation of foreignness in the play. The Spanish Tragedy takes place in the midst of Spain’s colonial expansion, following its annexation of Portugal. The characters represent an English imagining of Spanish and Portuguese persons, but the markers of cultural difference in the play are not specific to either population. Lorenzo’s identity as Spanish intersects with the blackface of the woodcut to perform an over-determined yet mutable racialized other that is above all non-English. The woodcut illustrates how easily categories of identity could be tried on, exchanged, and discarded on the early modern stage, while nonetheless suggesting that racial disguises ultimately result in failure.

Further Readings

Griffin, Eric. “Nationalism, the Black Legend, and the Revised ‘Spanish Tragedy.’” English Literary Renaissance 39, no. 2 (2009): 336–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6757.2009.01050.x.

Jakacki, Diane K. “‘Canst paint a doleful cry?’: Promotion and Performance in the ‘Spanish Tragedy’ Title-Page Illustration.” Early Theatre 13, no. 1 (2010): 13–36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43499547.

Mazzio, Carla. “Staging the Vernacular: Language and Nation in Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy.” Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900 38, no. 2 (1998): 207–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/451034.[199]

Beatrice Bradley

Case Study #2: Performance Culture: Masques, Carnival, Theatricality

Entry #35

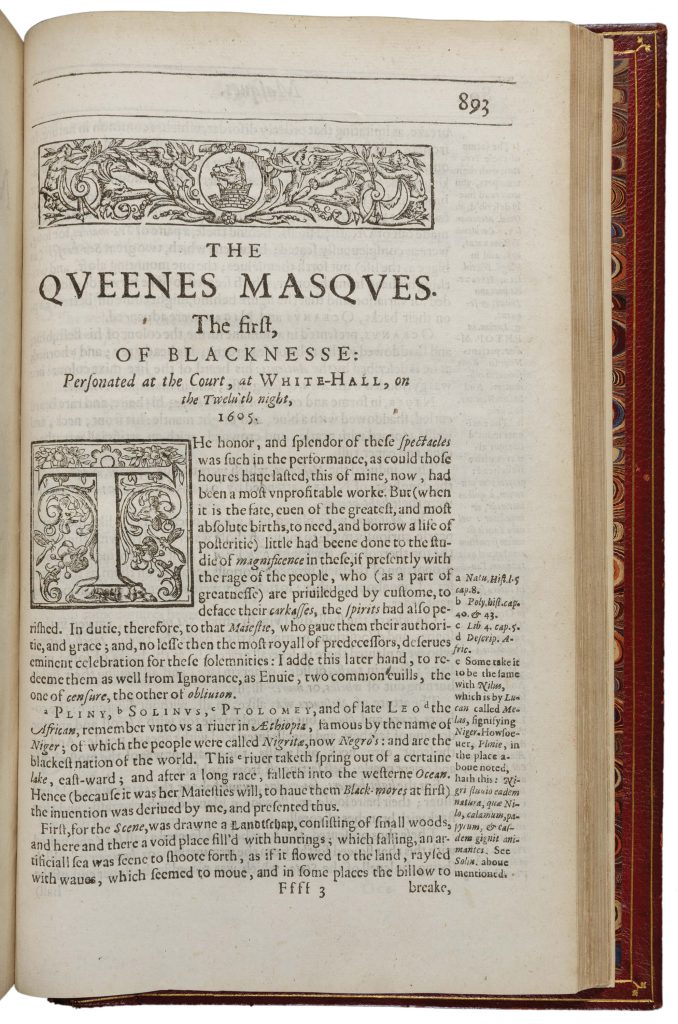

Jonson, Benjamin (1573?–1637), author

“[Masque] of Blacknesse” in The workes of Ben Ionson, 1616

Book with letterpress, engraving, and woodcuts

Case Y 135 .J735 v. 1

Masque of Blacknesse is the first masque to appear in the 1616 folio of Ben Jonson’s collected works. The masques of the Stuart Court combined dramatic action, musical song, and visual spectacular, and Jonson’s prefatory notes to Blacknesse in the folio illuminate an elaborate scene and stage setting. The masque was first performed in 1605, with a pregnant Queen Anne — wife to King James I — and multiple ladies of the court appearing in cosmetic blackface in the roles of “Ethiopian” nymphs. The short action of the masque follows Euphoris (Anne as fertility nymph) and her sisters in a quest to turn their skin white. Jonson’s introductory remarks emphasize the queen’s involvement and her professed desire that the masque include “Black-mores” (Ffff3r). Blacknesse also serves in support of James’ agenda of a unified “Great Britain,” with repeated praise of Britannia as a promised land in which the nymphs will achieve their desired whiteness. The fiction of Africa in the masque thus mobilizes a cultural understanding of Britain as an expansive, powerful, white nation that insistently reproduces its own whiteness.

In addition to Jonson’s introductory comments on Blacknesse, there exists a spectatorial account: Dudley Carleton, who attended the court performance, details in two letters the following year his revulsion in response to Anne’s painted face and arms (as opposed to the use of prosthetics such as a mask or gloves). Carleton provides a rare early modern response to the use of cosmetic blackface, and the masque more broadly locates Blackness as a site of spectacle in early modern England.

Further Readings

Hall, Kim F. “Sexual Politics and Cultural Identity in The Masque of Blackness.” In The Performance of Power: Theatrical Discourse and Politics, edited by Sue-Ellen Case and Janelle Reinelt, 3–18. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991.

Stevens, Andrea. “Mastering Masques of Blackness: Jonson’s ‘Masque of Blackness,’ The Windsor text of ‘The Gypsies Metamorphosed,’ and Brome’s ‘The English Moor.’” English Literary Renaissance 39, no. 2 (2009): 396–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6757.2009.01052.x.

Thiel, Sara B. T. “Performing Blackface Pregnancy at the Stuart Court: The Masque of Blackness and Love’s Mistress, or the Queen’s Masque.” Renaissance Drama 45, no.2 (2017): 211–36. https://doi.org/10.1086/694326.[201]

Beatrice Bradley

Entry #36

Jacques Callot (1592–1635)

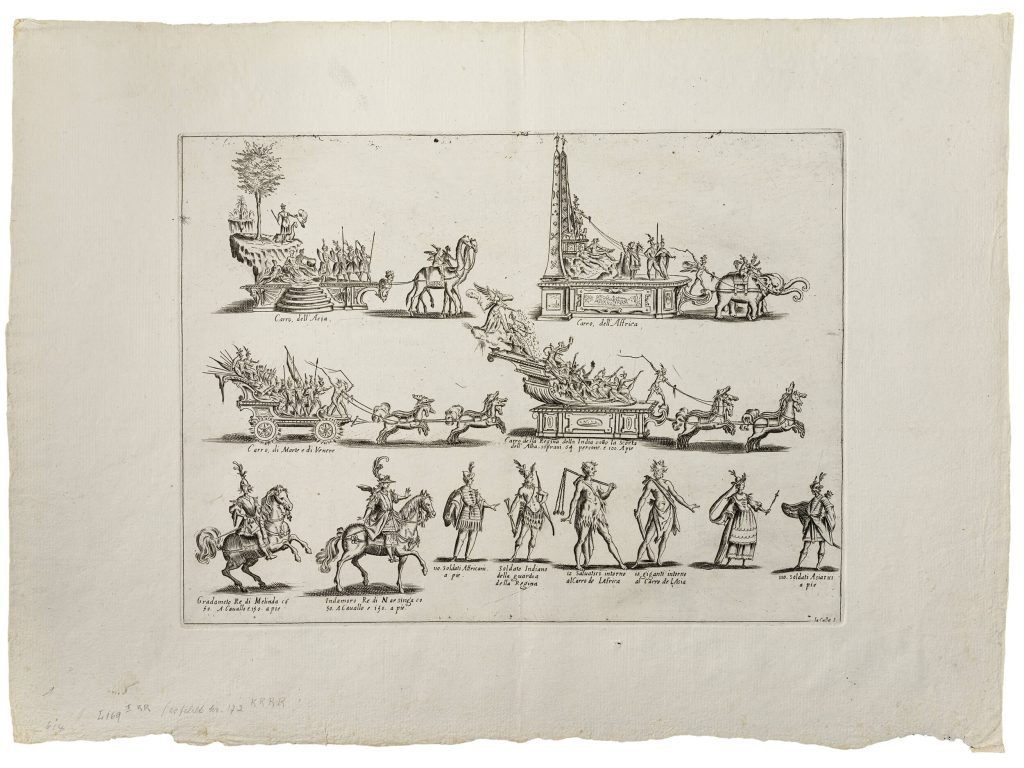

The Chariots and The Characters, from War of Love, 1616

Etching

Case V 461 .6773

The prolific French artist Jacques Callot documented Florentine spectacles in etchings and engravings from 1611 to 1621 during the reign of Grand Duke Cosimo II. This etching is part of a set of prints representing ephemeral events in Florence for carnival festivities in 1616 that included a procession, mock battle, and a horse ballet, entitled Guerra d’amore (War of Love). The single sheet prints are therefore often found folded and inserted into printed editions of the related libretto for Guerra d’amore. Working closely with other artists involved in Medici productions, Callot likely copied a drawing of an “Indian” by Giulio Parigi that might have functioned as a costume design for this event. Guerra d’amore included an elaborate battle between “Africans” and “Indians,” with one of the Kings played by the Grand Duke himself.

This sheet likely functions as a record of a procession in which Florentines dressed as “Indians,” Asians, and Africans performed race as they made their way through the streets of Florence to the piazza. The inscriptions on the etching tell us that the upper register of the print depicts the carriage or float for Asia and the carriage of Africa, while the middle register includes the float for Venus and a more elaborate float for the “Queen of India” that could hold “64 people seated and 100 people standing.” Finally figures at the base of the sheet reveal more detailed renderings of the figures costumed as soldiers, “savages,” kings, and queens of these other lands.

Further Readings

Bertelà, Giovanna Gaeta, and Annamaria Petrioli Tofani. Feste e apparati medicei: Mostra di disegni e incisioni. Florence: Olschki, 1969.

Boorsch, Suzanne. “America in Festival Presentations.” In First Images of America: The Impact of the New World on the Old, edited by Fred Chiappelli, 2 vols., 1:503–15. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

Wilbourne, Emily. “Music, Race, Representation: Three Scenes of Performance at the Medici Court (1608–1616).” Il Saggiatore Musicale 27, no. 1 (2020): 5–45.[204]

Lia Markey and Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Entry #37

Diego Valadés (1533–1582), author and engraver

Description of the sacrifices inhumanely made by the Indians of the New World, in particular in Mexico

[TIPVS SACRIFICIORVM QVE IN MANITER INDI FACIEBANT IN NOVO INDIARVM ORBE PRECIPVE IN MEXICO], in Rhetorica christiana, 1579

Book with letterpress and etching

Wing ZP 535 .P447

Fray Diego Valadés’ Rhetorica christiana (1579), the first book published by an American-born author (who was also the first mestizo to join the Franciscans in New Spain), illuminates the preaching practices of the Franciscan order in the Americas and argues for increased support from the Church and fellow ecclesiastics in the conversion of Indigenous peoples. Valadés himself participated in creating the 27 prints that are interspersed throughout the text, primarily constituting didactic tools for other missionaries. The single fold-out image in the Newberry edition, however, instead depicts a pre-Hispanic Indigenous town with a scene of human sacrifice prominently placed in the center.

The etching blends scenes of natural history and Indigenous customs like cooking, harvesting, and fishing. Small figures at work dot a landscape filled with European-style buildings, except for the large Indigenous temple (teocalli) at the center, inside of which lies a prone human body on the altar. A priest standing behind him proffers an object, likely the body’s heart, to a statue of an Indigenous god. To the right of the temple, an assistant throws the dead bodies of other victims down the stairs.

That Valadés’s publication was intended to be of practical use for other missionaries gives this depiction of Indigenous religious ritual a particular weight, which notably includes a dance performance taking place in a large clearing before the temple. The presence of the performance reveals the adaptations and concessions that missionaries were forced to enact in order to better resonate with Indigenous tradition and thus encourage conversions. The particular theatricality of Catholic monasteries (conventos) in the Americas reflected Indigenous practice and points to the ways in which Indigenous peoples expressed agency within a system intentionally designed to oppress and subjugate them.

Further Readings

Carrasco, Ronaldo. “El exemplum como estrategia persuasiva en la Rhetorica christiana (1579) de fray Diego Valadés.” Annales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 22, no. 77 (2000): 33–66. https://doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.2000.77.1939.

Galindo, David Rex. “Shaping Colonial Behaviours: Franciscan Missionary Literature and the Implementation of Religious Normative Knowledge in Colonial Mexico (1530s–1640s).” In Knowledge of the Pragmatici: Legal and Moral Theological Literature and the Formation of Early Modern Ibero-America, edited by Thomas Duve and Otto Danwerth, 296–327. Leiden: Brill, 2020.

Leaper, Laura E. “Time, Memory, and Ritual: Deciphering Visual Rhetoric in Diego Valadzés’s Rhetorica Christiana.” Ph.D. diss., New York University Institute of Fine Arts, 2012.[205]

Arianna Ray

Entry #38

Bernard Picart (1673–1733), engraver and etcher; Jean Frédéric Bernard (1680–1744), author

Page from nineteenth-century scrapbook with prints from the French translation, Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses des peuples idolâtres . . . représentées par des figures dessinées de la main de Bernard Picard, avec une explication historique & quelques dissertations curieuses, volume 3 (Religious Customs and Ceremonies of Idolatrous Peoples), 1723

Ayer 301 .C41 1723

In this print, eighteen partially nude adult bodies are represented mid-leap — arms apart and mouths agape — performing a lively circle dance to the percussive beat of two musicians on the right margin of the page. These figures, identified by the caption as Canadians making a sacrifice to the Quitchi-Manitou (Great Spirit), encircle a pyre of woven textiles, bolts of cloth, and stacked tambourines. These exotic materials of varied geographic origin, often labeled as “Indian” or “Moorish,” obfuscate any clear identification of the Indigenous Canadians in favor of collapsing Blackness and Indigeneity into a single foreign category. Published in 1723, this is one of 72 engravings in the third volume of Bernard Picart and Jean Frédéric Bernard’s Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses, compiled in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, which endeavored to introduce the people of the Americas to a European audience. Picart’s engravings relied on lively compositions of dance and nudity, rather than illustrating darker skin tones through cross-hatching, to construct racial difference on Indigenous bodies. As FitzPatrick and Fromont argue in “Back Bending Labor, Savage Dances, Pious Stances: Race in Motion between Africa and the Americas” in this volume, early modern iconography around the danse macabre and “Moorish” dance served to show animated bodily gestures as markers of lack of civility. Picart’s circle dance composition would likely remind viewers of the idolatrous account of Israelites dancing around the golden calf. Here, the early modern audience sees race as a performance, in which various ethnicities are conflated and made legible through choreography.

Further Readings

Gaudio, Michael. “Dancing in Circles: Ethnography and Animation in the Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses.” Paper presented at The Enlightenment Creation of World Religion: Bernard and Picart’s Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses Symposium and Research Methods Workshop, Newberry Library, Chicago, March 16, 2018.

Hunt, Lynn Avery, Margaret C. Jacob, and W. W. Mijnhardt. The Book That Changed Europe: Picart & Bernard’s Religious Ceremonies of the World. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2010.[208]

Stephanie Lee

Case Study #3: Performances of the Racial Self

Entry #39

Hans Förster (16th century);

block cut possibly by Monogrammist F. H. (active 1543–1553)

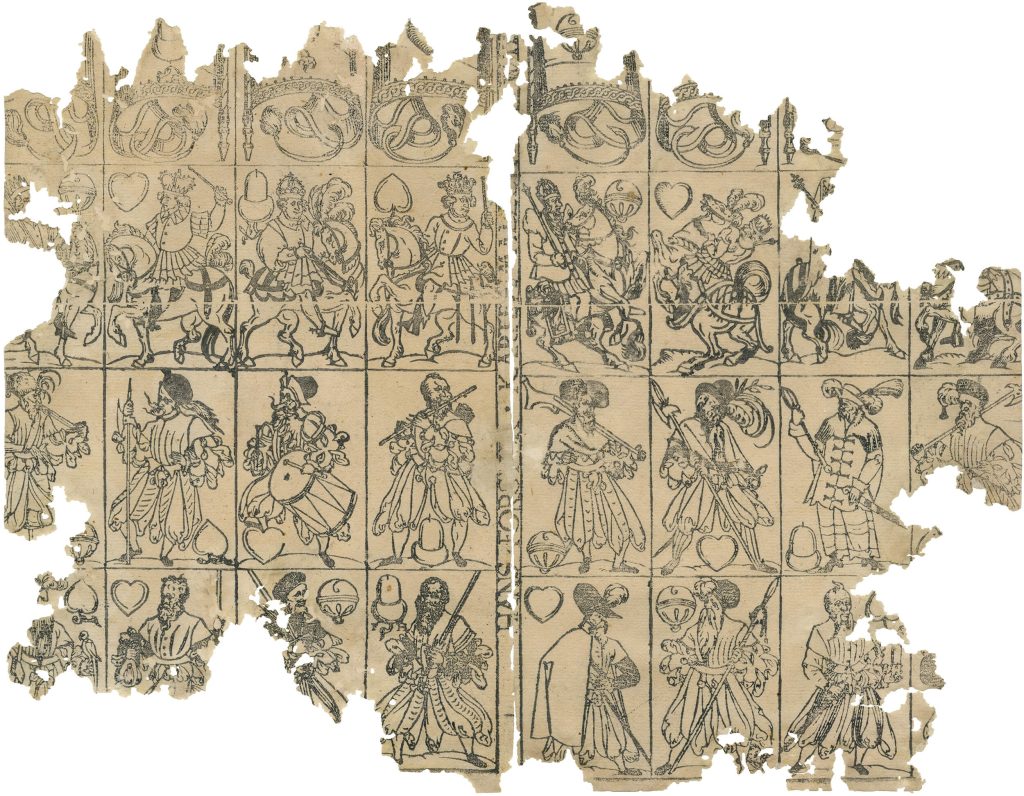

Playing Cards for the Game of Landsknecht, 1570s

Woodcut, fragment with two sets of face cards from three double sheets

Case Wing ZX 547 .F775

Premodern playing cards served many purposes and audiences — from lavish painted and gilded sets for aristocratic recipients to slapdash woodcut sheets with stenciled color for lowbrow gambling. Cards came to Europe from the Near East, probably in the fourteenth century, and were often banned, perhaps first in 1367 in Bern, Switzerland. This fragmentary sheet of 32 uncut woodcut cards was made in Vienna around 1570 in the workshop of Hans Förster. His signature describes him as a “Kartenmaler” or card painter, implying that the set was also available in color. While suits and face cards varied by country, the Germanic acorns, leaves, hearts, and bells seen here stayed relatively consistent. German face cards differentiated social status through clothing and appearance as well as the hierarchy of King, Upper Knave, and Lower Knave.

Unusually, Förster’s double sheet of face cards depicts the crowned kings on horseback and shows both groups of knaves as mercenary Landsknecht soldiers and musicians attired in their famously ostentatious dress. This sheet includes two sets of 16 slightly different face cards, both of which may have been intended for a popular game also called Landsknecht. The Lower Knave of Leaves on the right sheet, who holds a beer stein, seems from his topknot and long, parted beard to exhibit different ethnographic characteristics. He, and the knave of acorns above him with the toggle coat, are intended to appear slightly exotic, as Hungarian rather than German soldiers. They too were recruited as mercenaries for the Holy Roman Emperors. Playing card iconographies set up similar confrontations well into the nineteenth century by including contemporary portraits of rulers for one suit in opposition to unflattering images of non-European peoples for the others. For instance, Nuremberg artist Peter Flötner’s famous 1540 deck would pit the Emperor Charles V (King of Leaves) against a Turkish Sultan (King of Hearts), and an “Indian” ruler (King of Bells).

Further Readings

Husband, Timothy B. The World in Play: Luxury Cards 1430–1540. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cloisters, 2016. Exhibition catalog.

Leitch, Stephanie. Mapping Ethnography in Early Modern Germany: New Worlds in Print Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Pichler, Gerd. Die Spielkarten des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts in der Stiftssammlung St. Florian. Jahrbuch des Oberösterreichischen Musealvereines 142/1. Linz, 1997.[210]

Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Entry #40

Alvar Gonçalez el Moxo (16th century)

Carta executoria in favor of Alvar Gonçalez (patent of nobility), 1567

Illustrated manuscript on vellum

VAULT folio CASE MS 5248

This illuminated manuscript is a patent of nobility, a legal document containing the petition for recognition as a hidalgo (lowest rank of Spanish nobility) for Alvar Gonçalez el Moxo, resident of Campanario, Spain. The court granted his request on January 27, 1567. These petitions were written and illustrated to demonstrate factors recognized as essential to noble status such as service to the crown, religious devotion, and “purity” of blood. The Blood Purity Statues began in the mid-fifteenth century when civil and ecclesiastical institutions applied discriminatory segregation laws preventing Jewish converts from joining and holding office, the laws were later extended to anyone with Jewish, Muslim, or heretical lineage. If granted, the title of hidalgo conferred prestige and tangible privileges, such as exemption from taxes.

This manuscript, with its original gilt brown leather binding, shows the care taken to exemplify status, piety, and loyalty to the crown. The production of these manuscripts reached its peak in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. There are two full-page illustrations at the front of the manuscript. The first illustration is a devotional painting of the Virgin of Loreto holding the Christ Child with the much smaller aspiring hidalgos kneeling below. On the opposite folio, there is an image of Santiago Matamoros, or Saint James, the patron saint of Spain, known as the “Moor-Slayer.” Saint James, astride a white horse and dressed in elaborately adorned armor, rides into battle trampling figures representing the Moorish “Other.” This violent iconography reflects the dominant Catholic narrative of the warrior saint defeating the Muslim[211] infidels. Below, there is an illustration of the family’s coat of arms. The closeness of these two images is intended to signal the blood purity of the Gonçalez family and their religious fervor.

Further Readings

Domínguez Casas, Rafael. “Ascenso social y visualización simbólica del wwwwwpoder en dos ejecutorias de hidalguía del reinado de Carlos II.” Goya, no. 363 (2018): 108–25.

Matilla, Jose Manuel. “Símbolos de privilegio y objetos de arte. Los documentos pintados en la sociedad española del Antiguo Régimen.” In El documento pintado: cinco siglos de arte en manuscritos, 15–21. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, 2000.

Ruiz García, Elisa. “La carta ejecutoria de hidalguía un espacio gráfico privilegiado.” La España medieval, no. Extra 1 (2006): 251–76.

Elizabeth A. Neary

Entry #41

Pietro Ridolfi (active 1710–1723)

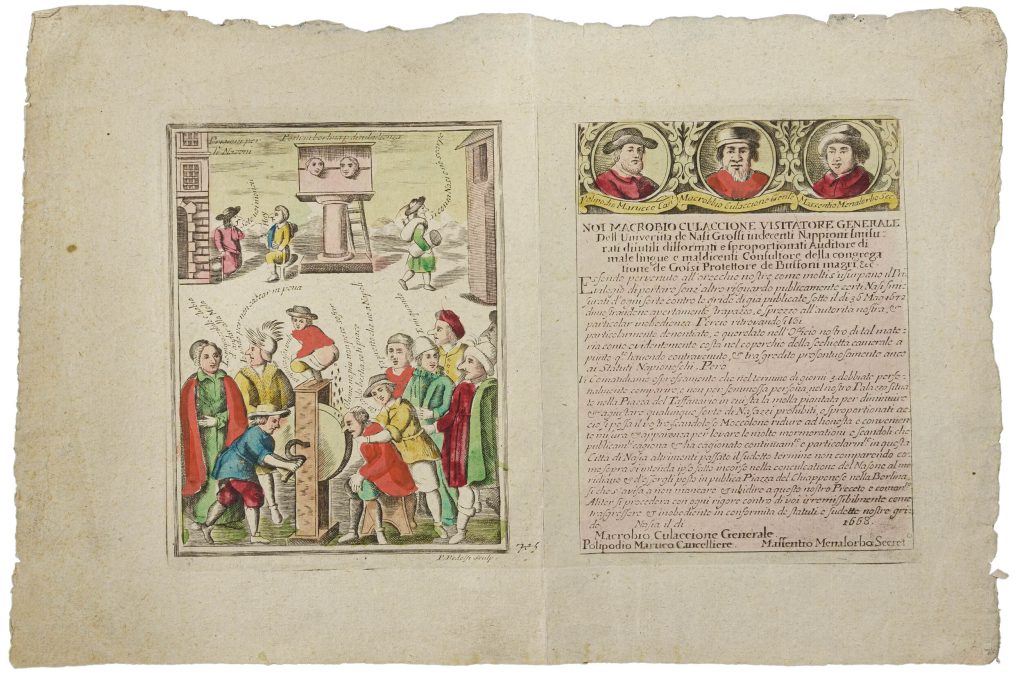

Fan-Shaped Diploma for the “University of Big Noses”

(Noi Macrobio Culaccione visitatore generale dell’Universita de Nasi grossi), eighteenth century

Hand-colored etching, folded

Case folio NC1529.R48 A7 1710

This satirical etching with anti-Semitic overtones is about “keeping one’s nose to the grindstone.” It consists of two complementary rectangles with a central gap on a sheet that folded together around a stick into a fashionable fan or ventole. Used to cool off attendees at outside festivals or inside church services, their imagery varied greatly. A certificate for the “Universita de Nasi grossi” or University of Big Noses, appears on one side, while the larger caricature on the other reveals the risks of enrolling in such a dubious, unaccredited institution. On the certificate, the university’s fictitious general, chancellor, and secretary appear above an extensive intaglio text explaining the danger of leaving big noses in their natural state. Viewers can fill in blanks with their own name (or of others whose noses they wished to ridicule). The caricature demonstrates the process of whittling down “indecent” noses on a grindstone lubricated with a cascade of feces. While the man whose nose is being reduced appears to struggle, the riveted crowd becomes tempted to undergo the same treatment.

This version of the print etched by Pietro Ridolfo was produced throughout the eighteenth century by the Remondini publishing firm, which offered fan prints in two sizes that were sold by peddlers throughout Italy and beyond. The certificate is dated 1668, suggesting it may have been based on an even earlier version. While the text is not explicitly anti-Semitic, this scatological satire of academia reinforces the undesirability of the oversized or hook noses that were already used to depict Jews in the early modern period. While meant to be a humorous, ephemeral accessory, the way it makes rhinoplasty a prerequisite for an academic education is deeply unsettling, and its racist overtones are unmistakable.

Further Readings

Harrán, Don. “The Jewish nose in early modern art and music.” Renaissance Studies 28, no. 1 (2014): 50– 70. https://doi.org/10.1111/rest.12006.

Infelise, Mario. I Remondini di Bassano. Bassano del Grappa: Ghedina & Tassotti, 1990.

Milano, Alberto. “Prints for Fans.” Print Quarterly 4, no. 1 (1987): 2–19.

———. “‘Selling Prints for the Remondini’: Italian Pedlars Traveling through Europe during the Eighteenth Century.” In Not Dead Things: The Dissemination of Popular Print in England and Wales, Italy, and the Low Countries, 1500–1820, edited by Roeland Harms, Joad Raymond, Jeroen Salman, 75–96. Leiden: Brill, 2013.[212]

Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Entry #42

Thomas Warmstry (1610–1665), author

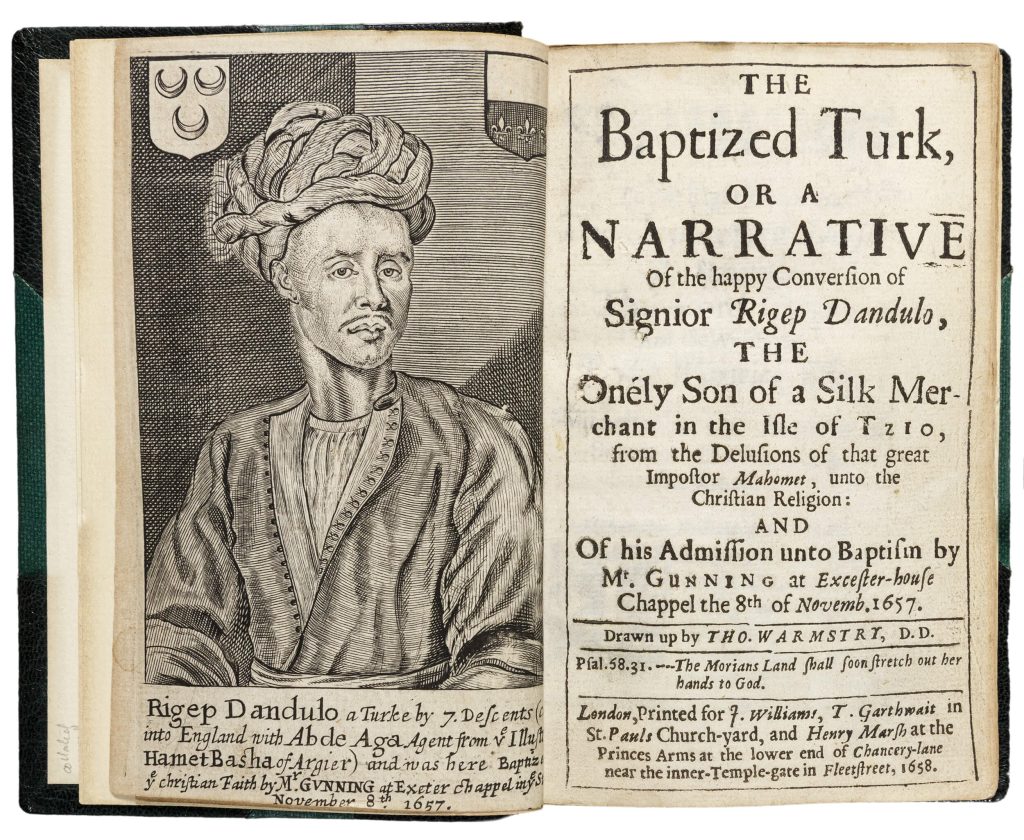

The baptized Turk, or, A narrative of the happy conversion of Signior Rigep Dandulo . . . from the delusions of that great impostor Mahomet, unto the Christian religion: happily begun by the author, and effectually prosecuted by the assistance of Mr. Peter Gunning. With the relation of his admission to baptism at Excester-house-chapel. the 8th. of November. 1657, 1658

Book with letterpress and engraving

Case C 6526.9546

The Baptized Turk is Thomas Warmstry’s 1657 account of the Anglican conversion of Rigep Dandulo, “an Islamic Turk.” England’s relation to the Ottoman Empire in the seventeenth century serves as a backdrop to the written account of Dandulo’s conversion and the image on the frontispiece in the Newberry’s edition. In early modern Europe, there was a general anxiety about Ottoman empire-building. However, England’s geographical location (far from Ottoman borders and oriented towards the Atlantic), political alliances, and shared enemies with the Ottoman assuaged some of those anxieties. Thus, Warmstry’s account precedes only by a few years the opening of highly popular Turkish-inspired “coffee shops” in London.

An examination of the frontispiece shows that this vision of Turks could be pressed into service. The portrait of Dandulo depicts him dressed in “traditional” Islamic clothes, an exaggeratedly large and intricate turban atop his head and a kaftan over his shirt. Two coats-of-arms are featured in the top corners of the portrait. While their meaning is unknown, in heraldry, crescents have Islamic origins, and the fleurs-de-lis are frequent symbols of the British monarchy. Therefore, holistically, this image foreshadows Dandulo’s conversion and enfoldment into British Protestantism. The broader function of conversion narratives during the seventeenth century was to simultaneously attack Catholicism and define Protestantism as the superior religion. Dandulo is a pawn in this war of religions; his compliance bolsters the power of Protestantism to “enlighten” and “civilize.” Therefore, this image is emblematic of race as power management.

Further Readings

Harper, James G. The Turk and Islam in the Western Eye: 1450–1750: Visual Imagery before Orientalism. Surrey, England: Ashgate, 2013.

Pearson, Jacqueline. “‘One Lot in Sodom’: Masculinity and the Gendered Body in Early Modern Narratives of Converted Turks.” Literature and Theology 21, no. 1 (2007): 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/litthe/frl060.

Katherine Chacon

European aesthetic movement that advocated for the revival of ancient Greek and Roman aesthetics in domains such as literature, music, art, or architecture

inferior, subordinate

relative to humanism, a European intellectual movement from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century characterized by a renewed interest in classical texts and epistemologies

stage scenery designed for a theatrical production

text to which an opera or other extended musical composition is set

public square in an Italian city

member of the Order of Friars Minor founded by St. Francis of Assisi in 1209

clergyman

German mercenary pikeman (a soldier armed with pike)

person who belongs to the lowest rank of Spanish nobility

printed from a plate on which the image is incised or engraved below the surface

observing the religion of the Church of England