Exhibition Catalog

Part 2. Mapping

[Print edition page number: 136]

Case Study #1: Medieval Epistemologies of Race and Geography

Entry #15

Sir John Mandeville, attributed author; Jean d’Outremeuse (1338–approximately 1399), possible author;

Cornelis de Zierikzee, printer

Iohannis de Montevilla Itinerari[us] in partes Iherosolimitanas: et in ulteriores transmarinas

(also known as the The Book of Sir John Mandeville), c. 1500.

Book with letterpress

VAULT Inc. 1498

(no image)

The Book of Sir John Mandeville chronicles Sir John Mandeville’s journey from St. Albans, England, eastward to the Terrestrial Paradise. Like many medieval itineraria, The Book allows its readers to visualize themselves journeying alongside Mandeville. The Book further functions mnemonically, similarly to a T-O mappa mundi, depicting wonders of the world in topical groupings and thus reflecting cosmological truths rather than geographical realities. Mandeville populates the East with people considered monstrous such as pygmies, Amazons, dog-headed people (cynocephali), and headless humans (blemyae). These peoples are depicted alongside vast civilizations, including enemy Saracen kingdoms in the Holy Lands, the Great Khan’s powerful empire of Cathay (China), and Prester John’s marvelous lands in India among the islands near the Terrestrial Paradise. Prester John, a Christian, is particularly notable for simultaneously representing a potential ally against the Saracens and a fearful yet desirable distant realm, filled with both gold and monstrous humans. In its depictions of the world, therefore, The Book both reflects and constructs a medieval European discourse of race.

Though Mandeville’s identity, possibly a pen name for Jean d’Outremeuse, is contested, The Book’s influence is undeniable. Its widespread reproductions have resulted in at least 25 different versions of the text. It was translated from French into nearly 10 languages across the European continent and likely influenced Christopher Columbus on his voyages to the Americas. This edition of The Book was printed in 1495 in Cologne, underscoring its longevity since the earliest surviving manuscript was penned in 1371.

Further Readings

Greenlee, John Wyatt, and Anna Fore Waymack. “Thinking Globally: Mandeville, Memory, and Mappaemundi.” The Medieval Globe 4, no. 2 (2018): 69–106.

Heng, Geraldine. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018, 127–38.

Tzanaki, Rosemary. Mandeville’s Medieval Audiences: A Study on the Reception of the Book of Sir John Mandeville (1371–1550). Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2003, 120–22.[137]

Jamie Keener

Entry #16

[Contextual Supplement: Racism in Action]

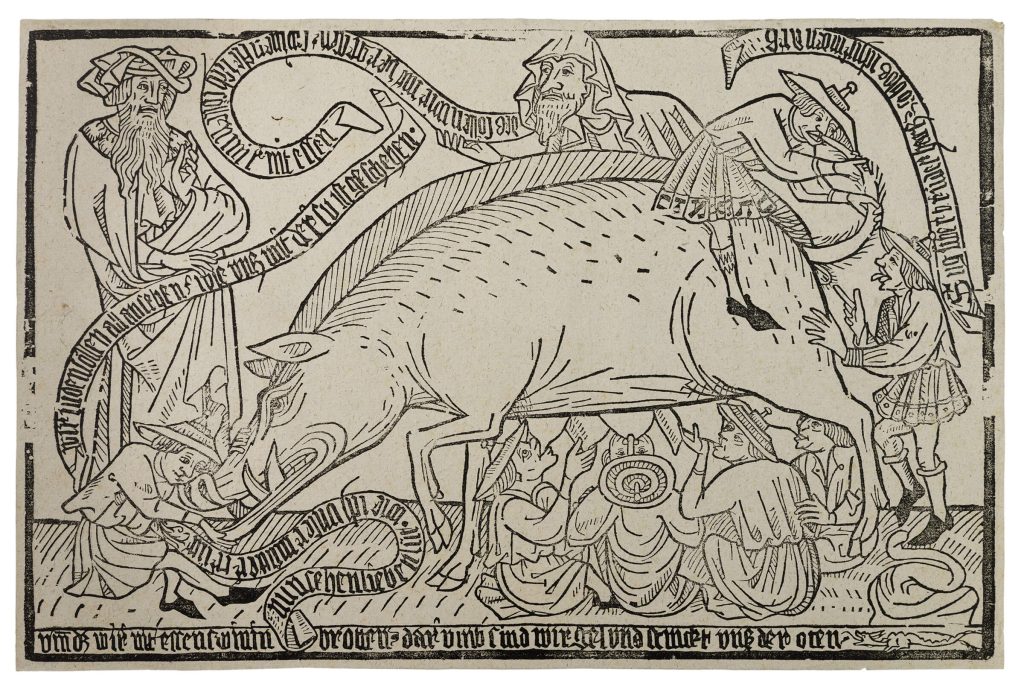

Unknown German artist

Judensau (Jew’s Sow), printed c. 1700

Woodcut on paper from a woodblock carved c. 1470

VAULT oversize fragment Inc. 37.7

The Judensau is an obscene antisemitic caricature dating back to at least thirteenth-century Germany. It shows a standing female pig surrounded by male figures depicted as Jews (with specific hats and somewhat large noses). They are caught in the transgressive acts of suckling on and caressing the animal and framed as rabbis ineffectively upholding the Torah’s prohibition on touching or consuming pork.

Initially an allegory of greed with no connection to Judaism, the Judensau later appeared in church sculptures and then on city gates and private property. Becoming even more widespread through prints, the theme persisted into the nineteenth century. The Newberry’s Judensau is the first complete printed image to survive, dating to around 1470. This oversized woodcut may have been displayed on walls. All known impressions were however printed about 1700 from the original block, which shows its age and the toll of frequent reprinting in its border losses.

The German caption below reads: “This is why we do not eat roast pork. And thus we are lustful and our breath stinks.” These insinuated bodily appetites pair with the stench of a curvaceous pile of porcine filth nearby. The image’s large scale further accommodates scurrilous texts implying other incestuous and unclean behaviors. The texts even appear as meaningless pseudo-Hebrew characters woven into the tunic hem of the Jew riding backwards on the sow. He raises her tail so another can inspect beneath it. Martin Luther described this scatological interaction in the still-extant Wittenberg Church’s Judensau statue in explicit terms in 1543, further cementing the damage of its perversely inverted iconography.

[138]

Further Readings

Luther, Martin. Vom Schem Hamphoras und vom Geschlecht Christi. Wittenberg: Georg Rhaw, 1543.

Shachar, Isaiah. The Judensau: A Medieval Anti-Jewish Motif and Its History. Warburg Institute Surveys, 5. London: Warburg Institute, 1974.

Wiedl, Birgit. “Laughing at the Beast: The Judensau.” In Laughter in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times: Epistemology of a Fundamental Human Behavior, its Meaning, and Consequences, edited by Albrecht Classen, 325–64. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010.

Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Entry #17

Hartmann Schedel (1440–1514), author; Michael Wolgemut (1434–1519), Wilhelm Pleydenwurff (1460–1494), and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), illustrators;

Anton Koberger (1440–1513), printer; Prince of Savoy (1663–1736), former owner

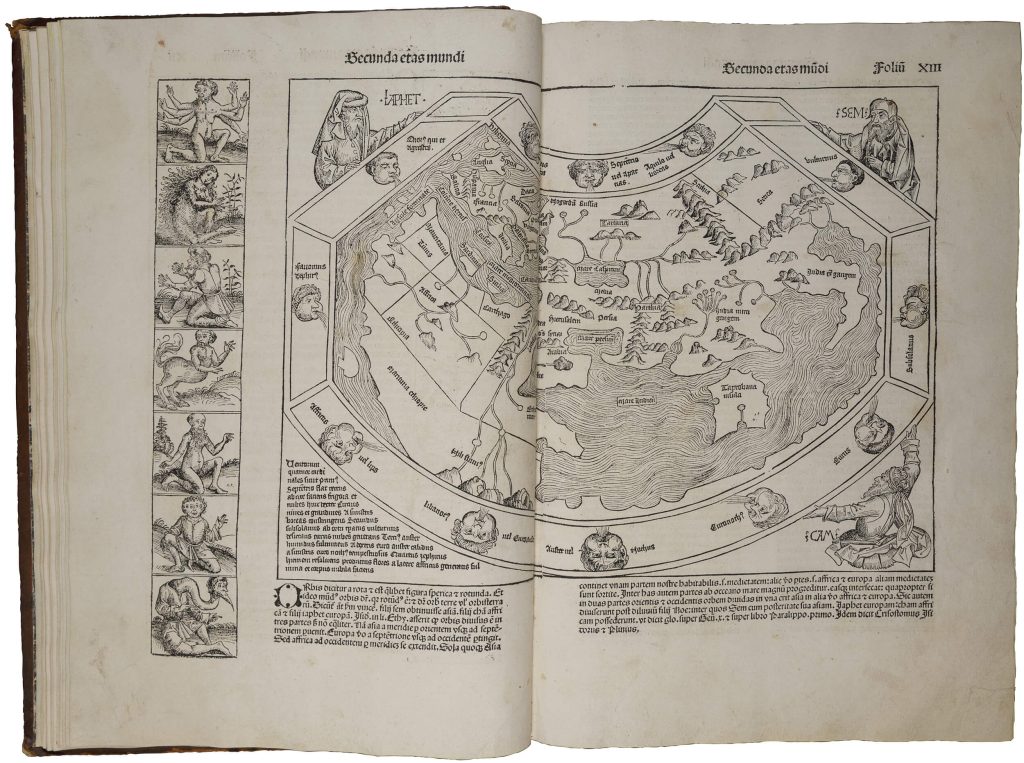

Map with Monstrous Races, in Liber chronicarum (also known as The Nuremberg Chronicle), 12 July 1493

Book with letterpress and woodcuts

VAULT oversize Inc. 2084

As detailed on its first page, the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle relates the histories of the world. Drawing from older models such as Ptolemy’s world map and Christian cosmography, this incunable, or early printed book, continued the medieval tradition of the mappa mundi and made it more accessible through its print format and later publication in a smaller, more economical edition. The Chronicle declared the centrality of Europe — particularly Nuremberg — and analogously, the cultural, religious, and moral superiority of the nations and continents at the center.

Folios XIIr–XIIIv depict the Second of the Seven Ages of the World, as per the Christian tradition. Dominating this two-page opening is the mappa mundi, held up in three corners by Noah’s sons, Japhet, Shem, and Ham. On the left, Africa appears below Europe; Asia reaches across the right side. Lining the left border of the page is a vertical grid exhibiting some of the “Monstrous Races”: the Six-Armed Man, Hermaphrodite, Twelve-Fingered Man, Satyr, Bearded Woman, Four-Eyed Ethiopian, and long-necked Crane Man. Unlike in medieval precedents, the “monsters” here are presented in a gallery on the border of the page rather than on the edge of the map. Natural landscapes frame the[139] figures in contrast to the elaborate cityscapes of European cities throughout the rest of the book. Despite the knowledge and depiction of Ethiopia on the map, a distorted representation of an Ethiopian appears outside of the centrally framed biblical narrative and attendant human lineage. Conveying with assumed authority a division between white and non-white humans, this historicized account provides a widely disseminated model of late medieval race-making. The first edition of this incunable appeared just before Columbus returned to Europe from the Americas.

Further Readings

Green, Jonathan. “Text, Culture, and Print-Media in Early Modern Translation: Notes on the ‘Nuremberg Chronicle’ (1493).” In Fifteenth-Century Studies Vol. 33, edited by Edelgard E. DuBruck, Barbara I. Gusick, and William C. McDonald, 114–32. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer, 2008.

Leitch, Stephanie. Mapping Ethnography in Early Modern Germany: New Worlds in Print Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Strickland, Debra Higgs. “Foreign Bodies in the Nuremberg Chronicle.” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 95, no. 2 (2019): 19–42.

Earnestine Qiu

Entry #18

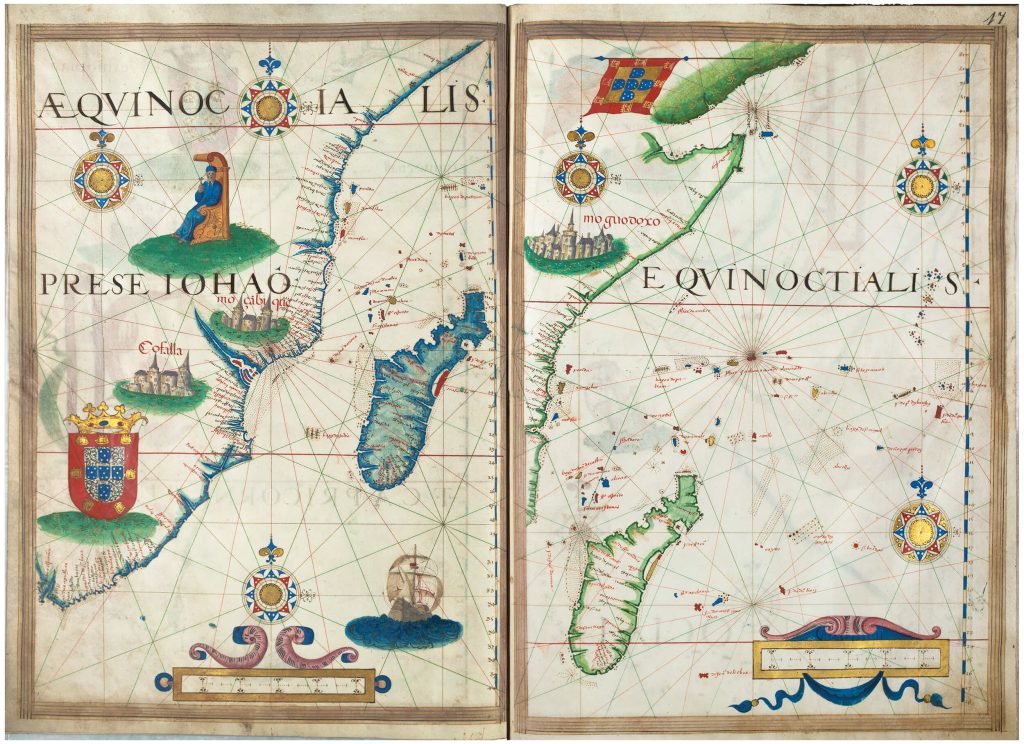

Sebastiao Lopes, sixteenth century

Portolan, 1565

Painted on vellum

Oversize Ayer MS map 26

A large-scale illuminated atlas on twenty-four pages of vellum in its original late-sixteenth-century binding, the Lopes portolan is an atlas designed for Portuguese royalty or the affluent merchant class. Its size, extensive gold leaf, and elaborately painted pages evoke luxury and wealth. Fingerprints in the bottom right corner of most of the pages indicate that it was also a beloved and often-studied manuscript. Portolan charts had been the most common and most accurate map for sea travel in the fifteenth century as they were based on measurements of coastlines and the use of the compass. By the mid-sixteenth century, when this atlas was produced, printed atlases were available and portolan charts were likely not used for the purposes of travel as frequently.

This portolan acts as a showpiece that propagandistically lays claim to Portuguese lands through the use of flags, coats-of-arms, architecture, and bodies. For instance, the pages representing Africa include Portuguese flags, a church, and numerous European townscapes. A central aim of the manuscript was also to demonstrate religious control over regions throughout the world. An enthroned Prester John presides over the east coast of Africa. Prester or Priest John, now a mythical figure, throughout the premodern period was believed to be a Christian ruler of Africa, possibly descendent from Asia and related to the Three Magi. He makes his way on to portolan charts as early as the mid-fourteenth century. Here on the Lopes portolan, as in other portolan atlases from the time, he is racialized through the depiction of dark skin.

Further Readings

Cortesâo, Armando, and Avelino Teixeira da Moto. Portugaliae monumenta cartographica, vol. IV (Lisbon, 1960).

Kaufmann, Miranda. “Prester John,” In Encyclopedia of Blacks in European History and Culture, edited by Eric Martone, 2 vols. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2009). II: 423–24.

Lanman, Jonathan T. “On the Origins of Portolan Charts.” The Hermon Dunlap Smith Center for the History of Cartography Occasional Publication, No. 2 (Chicago: Newberry Library, 1987).[141]

Lia Markey

Case Study #2: The Early Modern Turn Towards the Ottomans and the Americas

Entry #19

Robert the Monk and Fulcher of Chartres, authors

Hystoria de Itinere [con]tra turchos (Chronicle of the First Crusade), c. 1472

Book with letterpress

Inc. 998

(no image)

The Crusades caused a major shift in the medieval understanding of race, as they represented the most extensive interactions between some northern Europeans and non-Christian cultures since Late Antiquity. However, for the majority who never experienced one themselves, the Crusades were primarily a literary event. Widely held notions about the nature and purpose of the Crusades and the peoples involved were shaped far more by their depictions in chronicles, romances, liturgy, and other genres. As such, the conventions and stock characterizations of the vast body of Crusade literature fundamentally shaped how Europeans saw the non-Christian cultures of the Eastern Mediterranean long after the fall of the last Crusader kingdom in 1291. Chronicles of the First Crusade (none of which were true eyewitness accounts), for instance, depicted the Seljuk Turks as an inhuman, menacing force; the widely popular chronicle of Robert the Monk, for instance, described them as “abominable people” who “know nothing of God.” Though Crusaders themselves developed a more nuanced understanding of the different Islamic peoples they encountered, Europeans at home clung to these labels for centuries. During the fifteenth century, for example, editions of Crusade chronicles, such as the compilation shown here, were printed to help Europeans understand the ascendancy of the Ottoman Empire. Centuries later, Europeans would still rely on them to, once again, justify military and political attempts to reclaim control of lands in the Levant.

Further Readings

Lapina, Elizabeth. “Crusader Chronicles.” The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of the Crusades. Edited by Anthony Bale, 11–24. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Ramey, Lynn. Christian, Saracen and Genre in Medieval French Literature: Imagination and Cultural Interaction in the French Middle Ages. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2014.[143]

Christopher Fletcher

Entry #20

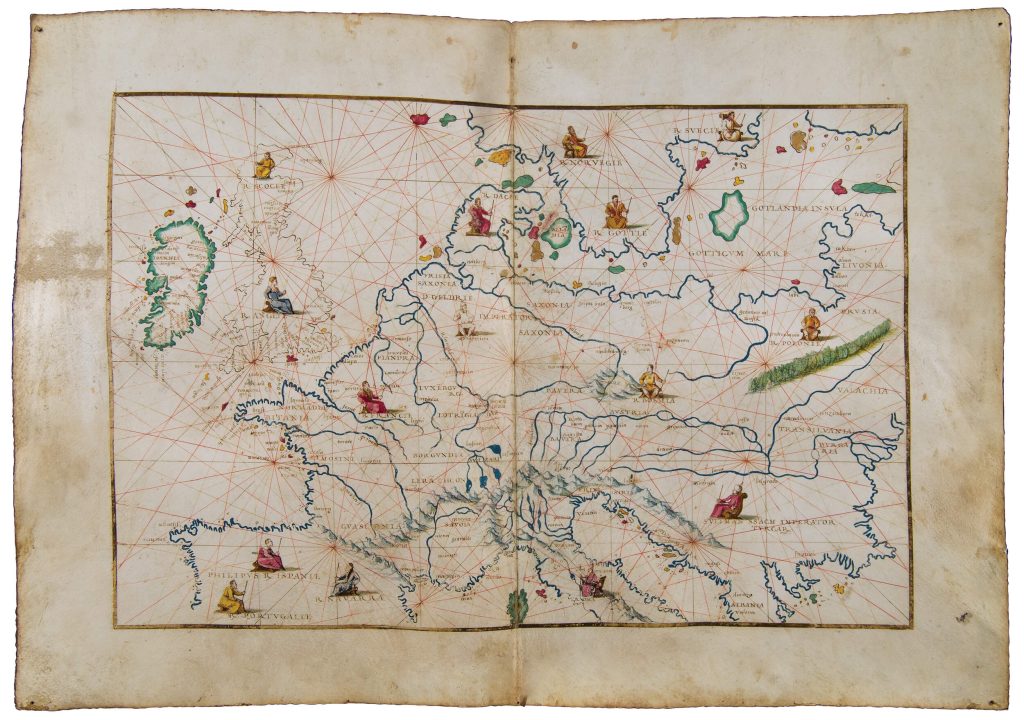

Attributed to Battista Agnese (1500–1564)

Manuscript portolan atlas of the world, 1550

Painted vellum

VAULT Ayer MS map 12.

Attributed to the prolific Genoese cartographer Battista Agnese, this portolan atlas offers a fascinating view of European expansion, self-(re)conceptualization, and assertion in the mid-sixteenth century. Portolan, or nautical, maps were originally used as navigational tools in late-medieval sea voyages, as evidenced by the network of ruled lines representing various wind directions in this example. By the time of the production of this atlas, however, the map’s artistic adornments and inland detail suggest they were becoming objects acquired as much for their decorative value. This degree of sophisticated decoration nevertheless points towards a new function by representing the ever-intensifying nexus between knowledge and power in Europe. On the folio presented, European monarchs emerge as generally standardized representations of sovereignty defined primarily over land rather than peoples. In contrast, every other region throughout the collection (including Africa, the Americas, and much of Asia) lacks human representations. Overall, the collection intimates European territorial control and opens non-European lands to conquest and material exploitation.

The sole non-European figure represented, the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, also captures the development of a distinct European identity in contrast to the non-European Other. Marked by his distinctive headwear and reclining aspect, Suleiman’s westward-facing profile is confronted by a generally united coalition of upright, standardized European sovereigns. This organization of figures carves out the core European territories as a culturally and religiously coherent unit in opposition to the non-European Muslim Sultan, marked out as he is from his counterparts through his dress, posture, and marginal position.

Further Readings

Astengo, Corradino. “The Renaissance Chart Tradition in the Mediterranean.” In Cartography in the European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 174–262. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Campbell, Tony. “Portolan Charts from the Late Thirteenth Century to 1500.” In Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean, edited by J.B. Harley and David Woodward, 371–458. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.[144]

Edward Johnson

Entry #21

Author Unknown

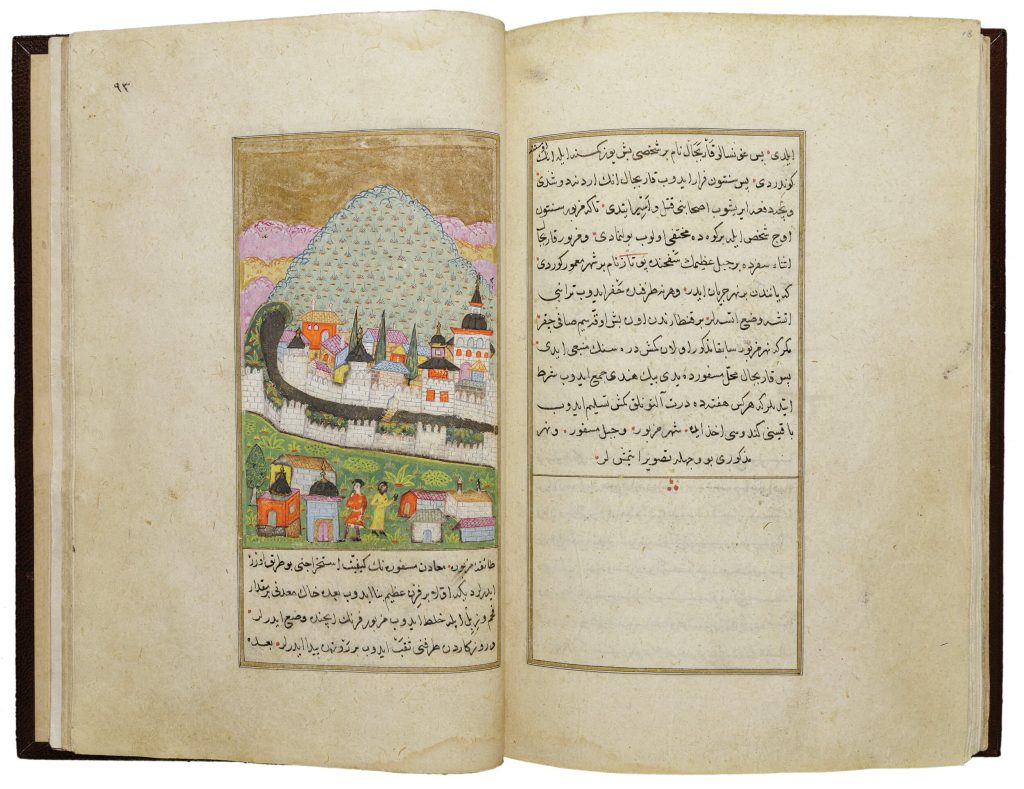

Tarih-i Yeni Dünya, el-musemma be hadis-i nev (A History of the India of the West), c. 1600

Painted on glazed paper

VAULT Ayer MS 612

This Ottoman Turkish manuscript fits in the palm of the hand and is composed of 107 pages with 13 images and 3 maps colorfully illuminated with gold and muted tones on a distinctly non-European glazed paper. The renowned manuscript in Turkish Arabic includes handwritten texts, maps, and images about the Americas based primarily on Giovanni Battista Ramusio’s third volume of the Navigazioni et viaggi, a compilation of travel writing about the world first published in Venice in 1565, as well as other Spanish publications, including Gómara, Oviedo, and Peter Martyr. The Newberry’s Tarih manuscript is one of 19 in the world that all derive from the same source. The original text was likely presented to Sultan Murad III in the late sixteenth century. The author/chronicler states in the first pages of the Newberry’s manuscript that he “collected some responsible truthful books and recent maps containing the. . . information, and after translating and commenting on them in general, a summary was set forth.”

Critical analysis of this “summary” in the text in relation to its complex images reveals intertextuality and representations of a changing world economy. For instance, the image of Potosì in the Newberry manuscript is borrowed from an Italian edition of Pedro Cieza de León’s 1553 chronicle of Peru, and the abundant use of gold leaf on the page seems to comment on the subject itself, reflecting the role of silver mining in the region. The figures at the bottom of the scene represent people of different races with a white man at left and Black man at right. Does the Black figure reference the enslaved laborers from Africa put to work in the mines in the region? In any case, the figure clearly delineates the distinctions between races described in the texts of illustrated travel accounts from this period but that are often not made apparent in the print medium.

Further Readings

Goodrich, Thomas D. The Ottoman Turks and the New World: A Study of Tarih-i Hind-i garbi and Sixteenth-century Ottoman Americana. Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz, 1990.

Leibsohn, Dana. “Made in China, Made in Mexico.” In At the Crossroads: The Arts of Spanish America and Early Global Trade, edited by Donna Pierce and Ronald Otsuka, 11–40. Denver: Denver Art Museum, 2012.

Tezcan, Baki. “The Many Lives of the First Non-Western History of the Americas: From the New Report to the History of the West Indies.” The Journal of Ottoman Studies, 40 (2012): 1–38.[147]

Lia Markey

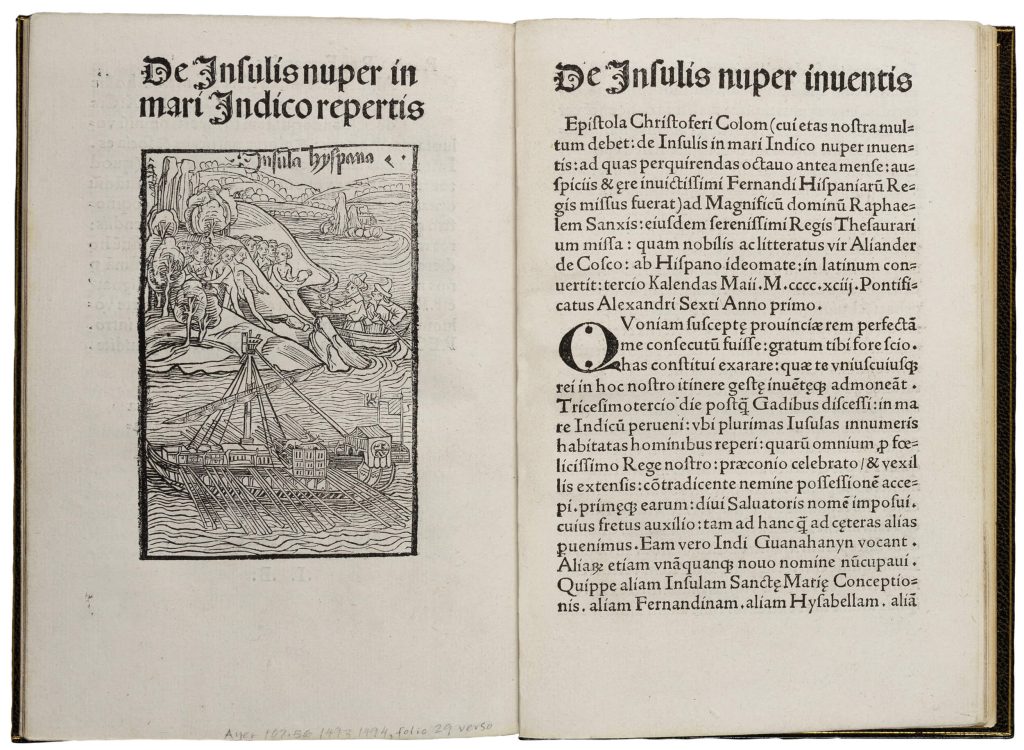

Entry #22

Carlo Verardi (1440–1550), author,

In laudem Serenissimi Ferdinandi Hispaniarum regis Bethicae & regni Granatae obsidio, victoria, & triumphus (In Praise of King Ferdinand), 1494

Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), author; Leandro di Cosco, translator (Spanish text into Latin); Anonymous woodcutter

De insulis in Mari Indico nuper inuentis (Of islands recently discovered in the Indian Ocean), 1493

Book with letterpress and woodcuts

Vault Ayer 105.56 1493

Two books are bound together in this Latin edition: a play entitled In laudem Serenissimi Ferdinandi Hispaniarum regis Bethicae & regni Granatae obsidio, victoria, & triumphus, and a Latin translation of a letter sent by Christopher Columbus to the royal treasurer Rafael Sánchez in 1493. Written by the Italian Humanist Carlo Verardi and dedicated to Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, the former dramatizes the end of the Reconquista, a long period of Christian military campaigns against Muslims in Spain. Granada, Iberia’s last Islamic kingdom, would surrender to the forces of the Catholic Kings in January 1492. The frontispiece woodcut shows Ferdinand holding the shields of the two kingdoms, Castile and Leon, and Granada.

The second text is a letter written by Columbus where he describes the geography and natural landscape of the Caribbean islands, as well as the physical aspect, customs, and character of its native population. The letter is accompanied by a[149] renowned woodcut (based on a woodcut in the Pforzheim’s edition of Columbus’s letter printed in Basel in 1493) depicting the ships arriving at a bountiful but uncultivated land. Columbus is shown approaching a group of nude Indigenous Americans who appear fearful of the encounter. The idea of the Americas as a naturally marvelous land inhabited by uncivilized and simple-minded peoples — the so-called Noble Savages — would spread across Europe, serving to justify future colonial enterprises.

The juxtaposition of the two texts articulates a narrative of Imperial expansion in the name of Christianity. Verardi’s play functions as a precedent and justification to Columbus’s mission, and consequently, to the oppression of non-Christian bodies. Considered together, these texts offer a racialized vision of religion.

Further Readings

Fuchs, Barbara. Mimesis and Empire: The New World, Islam, and European Identities. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Zamora, Margarita. Reading Columbus. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.[150]

Daniela Gutiérrez Flores

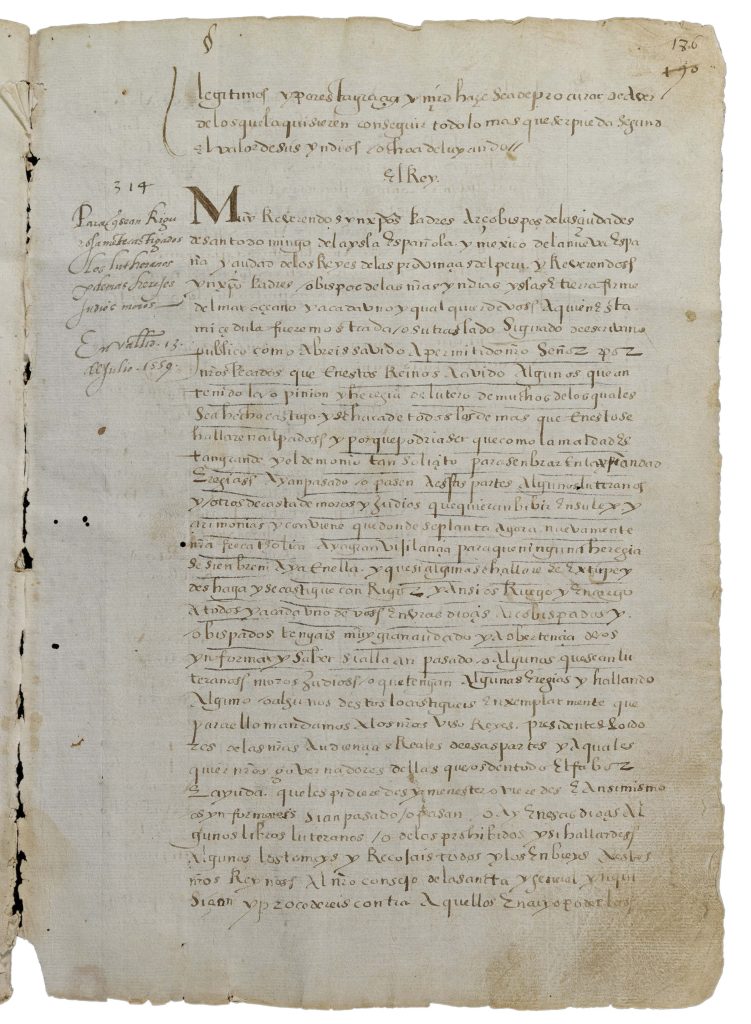

Entry #23

Philip II, King of Spain (1527–1598), original author; Scribe unknown

Official copy of royal cedulas from the real cedulario of the Audiencia de Guatemala, 1559

Manuscript leaves in red morocco slipcase

VAULT Ayer MS 1917

In September of 1543, the Spanish Crown established a centralized high court in Central America called the Audiencia de Guatemala to control conquistadores who were severely abusing Indigenous populations and trading them around like private property. The Audiencia began issuing royal cedulas, or decrees, addressing a range of matters, that were copied into a royal cedulario, a portion of which is presented here. The Newberry manuscript contains leaves 179–190 with cedulas numbered 291–315, dated from 17 January 1556 to 8 September 1559 and directed by King Phillip II. The matters addressed are administrative, legal, and concern the specific management and punishment of racially subjugated populations: Indigenous people, Jews, Lutherans, and Moors. Signs of use on the corners and sections that appear to have been underlined by another hand evidence the standardized referencing of the royal cedulario. Sections are briefly summarized in the margins for quicker navigation.

The royal cedulas and cedulario were crucial to the invention of race in colonial Central America, revealing the legal foundations of the racial distribution of power. These specific cedulas reflect aspects of segregationist policies that controlled how the “indios” were to interact with the justice system, pay specific taxes, and even conduct Mass. While some cedulas tried to better conditions for the Indigenous, they also sanctioned encomienda labor laws, perpetuating the dehumanization and distribution of Indigenous slave labor. Any new decrees from the Spanish Crown that threatened the power and racial superiority of encomenderos were either ignored or fiercely opposed.

Further Readings

Kramer, Wendy. Encomienda Politics in Early Colonial Guatemala, 1524–1544: Dividing the Spoils. Boulder: Westview Press, 1994.

Rodríguez Becerra, Salvador. Encomienda y Conquista: Los inicios de la colonización en Guatemala. [Sevilla]: Publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla, 1977.[151]

Andrés Irigoyen

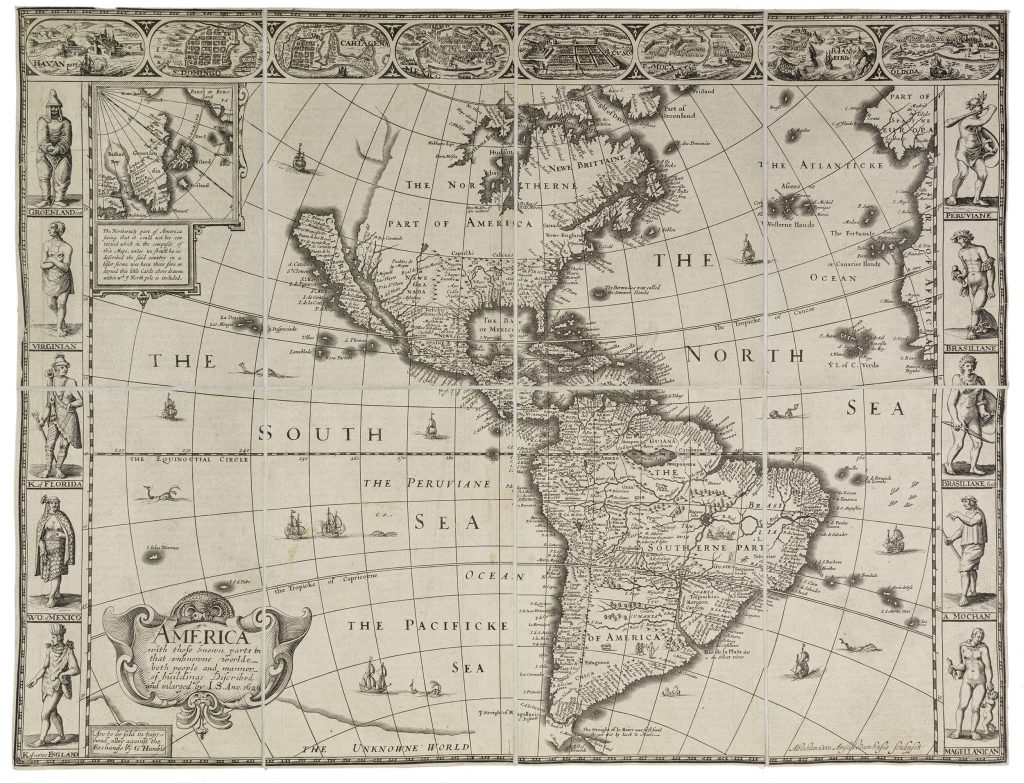

Entry #24

John Speed (1542–1629); Abraham Goos (1590–1643), engraver

America with those known parts in that unknown worlde both people . . ., 1626

Folded engraved map

Ayer 133 S.74 1626

This engraving represents the first edition of John Speed’s popular map of the Americas, which was subsequently reprinted in various editions throughout the seventeenth century. A renowned cartographer and historian based in London, Speed produced countless maps of the counties of England as well as world atlases. He worked primarily with the Dutch engraver Abraham Goos, who specialized in producing cartographic prints in Antwerp. This folded engraved map was likely sold as a single sheet print to be collected in an album or hung on a wall. The print can also be found in editions of Speed’s A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World (1627).

Unlike portolan charts (Cat. Nos. 18 and 20) where bodies are often represented within the map, here the bodies border the map. Yet Speed’s representation of vignettes framing the map with depictions of cities and Indigenous figures from different regions is not the first of its kind. Already in 1572 Georg Braun and Franz Hogenburg developed this format in some of their maps in the Civitates Orbus Terrarum. In the Speed map, the racial profiling inherent in costume books like Vecellio’s Habiti antichi e moderni (1590) (Cat. No. 8) merges with the map to produce a new genre of cartography. In fact, many of the men and women represented on this sheet are borrowed from figures in costume books and from de Bry’s Grand Voyages.

Further Readings

Speed, John. A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World. London, 1627.

Tooley, R.V. The Mapping of America. London: The Holland Press, 1980.

Traub, Valerie. “Mapping the Global Body.” In Early Modern Visual Culture: Representation, Race, and Empire in Renaissance England, edited by Peter Erickson and Clark Hulse, 44–97. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000.[153]

Lia Markey

Case Study #3: Further Expansion

Entry #25

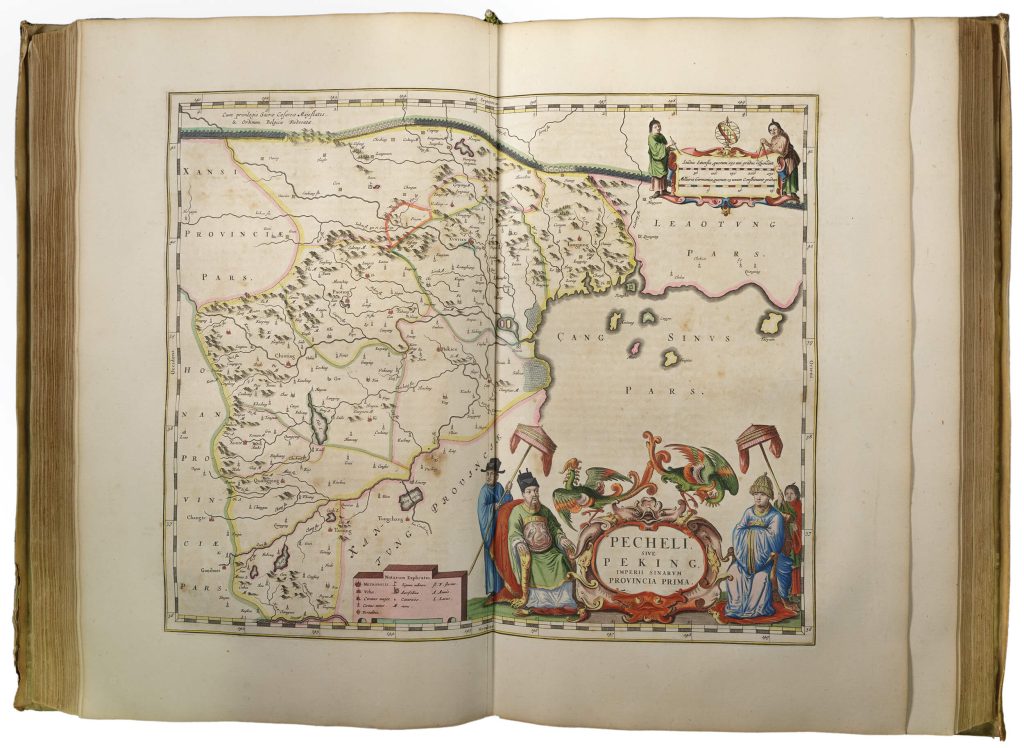

Joan Blaeu (1596–1673), cartographer

Pecheli, sive Peking Imperii Sinarum provincia prima (Map of Peking), in Le grand atlas, 1663

Book with letterpress and engravings

VAULT Ayer oversize 135 .B63 v. 11

With the publications of cartographer Joan Blaeu, detailed maps of China were for the first time brought under the voracious eye of wealthy Europeans. This map of Peking (now Beijing) published in 1663 initially appeared a decade prior as part of Blaeu’s seminal atlas on China, which collated a series of maps translated from Chinese sources by the Jesuit missionary Martino Martini. As the official cartographer of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), Blaeu produced maps that were intimately intertwined with the ambitions of the Dutch global elite attempting to acquire Chinese trading privileges. Though based on Chinese sources, the map was modified to fit a European prototype. The sizeable title is framed by a couple and two servants and topped by two phoenixes (fenghuang) while the scale at upper right is embellished by two Chinese men holding the cartographic tools with which, the image suggests, they made the map upon which the beholder currently gazes. The inclusion of the cartographers appealed to the fascination with Chinese cultural products while also visually asserting the map’s non-European origins.

The uneven relationship between Europeans and the Chinese, wherein the latter held greater economic power and the former hungered for Chinese wares, affected the racialization of the map’s figures. In terms of their dress, the embroidered birds on the left man’s robe, for instance, accurately mark him as a civil official, though his servant’s winged hat was reserved for bureaucrats, indicating a lapse of understanding in favor of exoticizing differences. The elegant silk garments allude to their material wealth and status, while the talon-like fingernail guards (another accurate representation of high-class fashion) develop the sensational animalistic imagery of the clawed armchair and phoenixes. These elements denote the figures’ corporeal difference and mark a visual boundary between the mapped bodies and the European viewer.

Further Readings

Cams, Mario. “Displacing China: The Martini-Blaeu Novus Atlas Sinesis and the Late Renaissance Shift in Representations of East Asia.” Renaissance Quarterly 73, no. 3 (2020): 953–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/rqx.2020.123.

Finnane, Antonia. “Fashions in Late Imperial China.” In Changing Clothes in China: Fashion, History, Nation. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

Zandvliet, Kees. “Mapping the Dutch World Overseas in the Seventeenth Century.” In The History of Cartography, vol. 3, part 2, edited by David Woodward, 1433–1462. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.[155]

Emily Kang and Arianna Ray

Entry #26

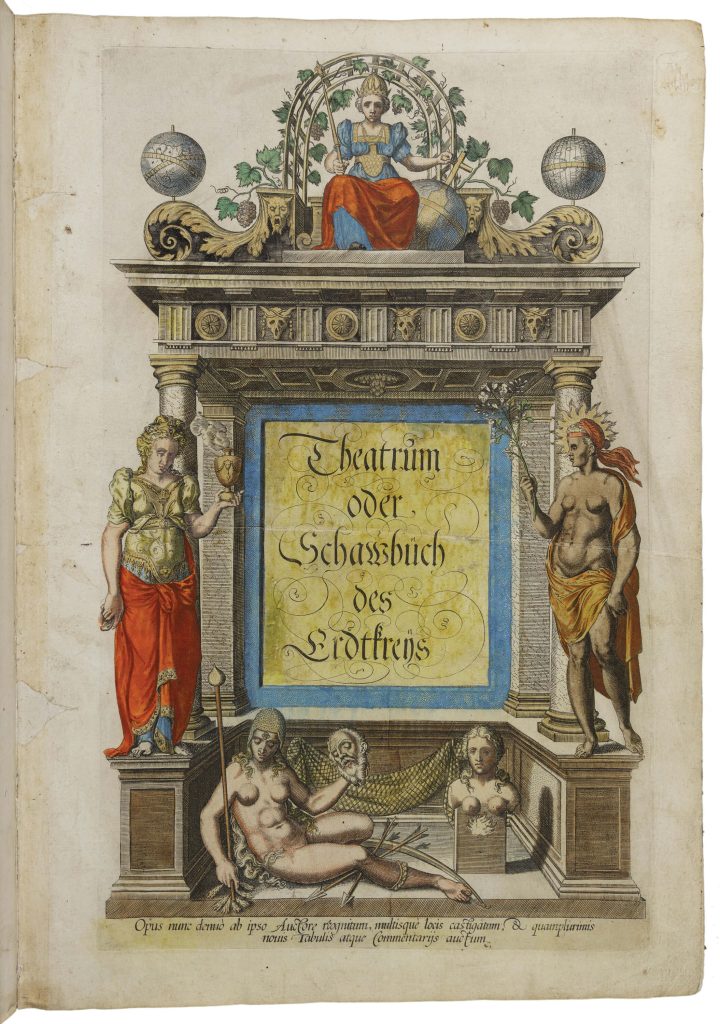

Ortelius, Abraham (1527–1598), author; Christoffel Plantin (1520–1589), publisher

Theatrum oder Schawbüch des Erdtkreijs: opus nunc denuò ab ipso auctore recognitum, multisquè locis castigatum quamplurimis nouis tabulis atque commentarijs auctum (Theater of the World), 1580

Book with letterpress and colored engravings

VAULT Baskes oversize G1006 .T515 1580b

Abraham Ortelius’s Theater of the World is the earliest printed volume to assemble cartographic knowledge in the format that we would today recognize as an atlas. The volume presents commentary and maps of global geography, assembled from a variety of sources and standardized. As a portal into this constructed world, the volume’s frontispiece characterizes the places the reader will explore by reading and provides categories through which to imagine the people that lived there. It asserts a hierarchy that subordinates other lands and their inhabitants to Europe and Europeans.

Personifications of four continents pose around a theater. Europe, at top center, sits enthroned. Her crown and scepter imply her dominion over the continents below. Her Christ-like pose and cross-surmounted globe ground that dominion in Christianity. At left, Asia, richly dressed in robes, holds a smoking censer filled with incense. Africa stands at right, poorly clothed from the waist down. In the Newberry’s volume, her skin is painted brown. Although some of the coloring in this volume was likely added after the nineteenth century, later editions of the frontispiece consistently repeat this coloring. America, wearing only an anklet and helmet, carries a cudgel, bow, arrows, and a decapitated human head. These violent attributes argue that the continent is dangerous to Europeans who travel there and apply centuries old tropes regarding cannibals living at the edges of the earth to the inhabitants of the Americas. At the same time, America, lying beautiful and naked on the ground, is presented as ready to be ravished by Europeans.

Further Readings

Binding, Paul. Imagined Corners: Exploring the World’s First Atlas, 209–20. London: Headline, 2003.

Horowitz, Maryanne Cline. “Rival Interpretations of Continent Personifications.” In Bodies and Maps: Early Modern Personifications of the Continents, edited by Maryanne Cline Horowitz and Louise Arizzoli, 1–24. Leiden: Brill, 2020.

van den Broecke, Marcel P. R. Ortelius Atlas Maps: An Illustrated Guide. Netherlands: Hes & de Graaf Publishers, 2011.

Olivia Dill

travelogue

in the manner of a device that helps memorize something

medieval map of the world representing the Mediterranean, the Nile, and the Don River conjoined to form a “T” separating Europe, Africa, and Asia, all encircled by the Ocean in the form of an “O”

person who has both male and female reproductive organs

in Greek and Roman mythology, minor forest deity having both human and goat-like features

parchment of superior quality made from the skin of calves

form of public worship, especially in the Christian Church

(obsolete) stretch of land in the Eastern Mediterranean corresponding to today’s Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and some Turkish regions

fine flexible leather from goatskin tanned with sumac

patent granting conquistadores the right to colonial lands and to the labor of enslaved Indigenous people on those lands

encomienda beneficiary