Exhibition Catalog

Part 1. Figuring

[Print edition page number: 52]

Case Study #1: Imagining Blackness

ENTRY #1

Franciscan Bible, Paris, c. 1250

Manuscript on parchment with illuminations

VAULT Case MS 19

(no image)

The Bible was the foundation for almost all learning, worship, and art in medieval Europe. As such, the central text of Christianity served as the primary lens through which highly trained intellectuals as well as unlearned peasants visualized everything in their world, including race. The biblical texts include multiple references to people of color, both literary (e.g., the “black yet beautiful” woman in Song of Songs 1:4) and historical (e.g., the Ethiopian eunuch converted by the Apostle Philip in Acts 8: 26–40), which became entrenched in European culture through commentaries, sermons, devotional literature, and visual art. The presence of non–white people in the Christian story was shared more widely starting in the thirteenth century, when Franciscan and Dominican friars used small, complete copies of the Bible to minister to increasingly diverse audiences. The example here was certainly used for this purpose; alongside the full Biblical text, it featured exquisite illuminations and supplementary texts for saying mass and managing devotional practices, all of which helped to bring biblical material to Christians outside the intellectual elite. Over time, laypeople took the biblical content they learned from these encounters to shape their own devotional lives. The cultural significance of the Bible ensured that race was firmly implanted within the European imagination, where it could be employed in a variety of ways to visualize the world, the different peoples within it, and the power dynamics between them.

Further Readings

Light, Laura. “The Thirteenth Century and the Paris Bible.” In The New Cambridge History of the Bible: from 600 to 1450, edited by Richard Marsden and E. Ann Matter, 380–391. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Van Engen, John. Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life: The Devotio Moderna and the World of the Later Middle Ages. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, esp. 266–304.[53]

Christopher Fletcher

ENTRY #2

Ludolphus de Saxonia (c. 1295–1378), attributed

Le miroir de humaine saluation (Mirror of Human Salvation) 1455

Parchment with ink and gold leaf

VAULT folio Case MS 40

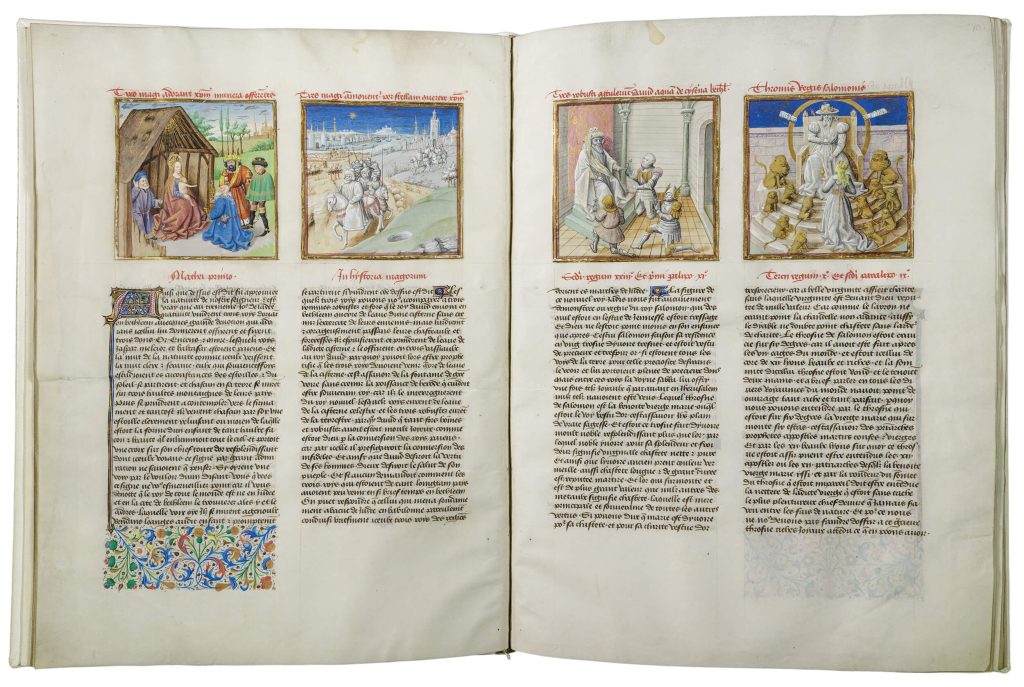

Illuminated in Flanders by an unknown artist, this French manuscript associates Christian salvation with whiteness. Translated from its Latin original, Le miroir de humaine saluation explains salvation through typology — a method of biblical interpretation whereby events drawn from the Hebrew Bible were read as prophetic symbols of the New Testament. This artist used grisaille, a technique for evoking depth in stone sculpture, in the three prefigurative scenes to convey how, just as colorful realism replaces inanimate stone, what was unrefined in the Hebrew Bible would be fulfilled by the New Testament. Across two pages side by side, the Adoration of the Magi is juxtaposed with a star guiding the Magi to Christ, three Israelite soldiers before King David, and the Queen of Sheba paying homage to Solomon, each prefiguration intended to prophesize the universal mission of Christendom that would draw Gentiles and Jews towards Christ.

Solomon’s ivory and gold throne was understood as a symbol of the Virgin Mary because ivory’s “whiteness and coolness,” as the text underneath the scene describes, symbolized her virginity. Delicate lines of gold embellishment adorn the white throne, mirroring the pale skin and blonde hair of the Virgin on the opposite page. Noticeably, the African Queen of Sheba and the Magus Balthazar are depicted with light skin and the Queen is seen from behind. European artists increasingly represented both figures with dark skin from the eleventh to the fifteenth centuries, and Balthazar in particular was painted Black in other Miroirs produced in Flanders in the mid-1400s. This manuscript perhaps more closely reflects the conventions of medieval French romances that represented Saracen women who converted to Christianity or aided French armies with pale skin to convey virtue.

Further Readings

Kaplan, Paul. The Rise of the Black Magus in Western Art. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1985.

Weever, Jacqueline de. Sheba’s Daughters: Whitening and Demonizing the Saracen Woman in Medieval French Epic. East Sussex: Psychology Press, 1998.

Wilson, Adrian, and Joyce Lancaster Wilson. A Medieval Mirror: Speculum Humanae Salvationis 1324–1500. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.[54]

Caitlin DiMartino

ENTRY #3

Wolfram von Eschenbach (c. 1160/80–c. 1220), author

Parsival, 1477

Book with letterpress

VAULT folio Inc. 216

(no image)

Although evidence indicates that people of color were physically present throughout Europe during the Middle Ages, white Europeans also “saw” them depicted in literary works. In these contexts, readers and hearers had the opportunity to play with the meaning behind phenomenological differences like skin color. One of the clearest examples of this approach to seeing race is the character of Feirefiz, a biracial knight who plays a prominent role in Parsival, the most popular Arthurian romance in medieval Germany. The son of a white Christian knight and a Black “Saracen” queen, Feirefiz literally embodies the competing natures of his racial heritage: his skin is described as a patchwork of black and white “like a magpie,” and he simultaneously displays the qualities white, noble Europeans ascribed to themselves (courage, martial skill, courtesy) and those they ascribed to non-white “Others” (ignorance of Christianity, pride, wealth). Medieval audiences thus understood Feirefiz not as an accurate representation of a biracial person (which many could certainly have seen in person), but as an invitation to playfully envision the social, moral, and biological implications of racial difference. This open-minded approach to seeing race contributed to Parsival’s enduring popularity during the Middle Ages (parts of it survive in nearly hundred medieval manuscripts and the 1477 printed edition shown here), but fell out of favor in the early modern period, when the colonial system demanded more stringent legal distinctions between white Europeans and the peoples of color they subjugated and enslaved.

Further Readings

Hahn, Thomas, ed. Special Issue on Race and Ethnicity in the Middle Ages. Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 31, no. 1 (2001).

Heng, Geraldine. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018, esp. 181–256.

Whitaker, Cord J., Black Metaphors: How Modern Racism Emerged from Medieval Race-Thinking. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019.[57]

Christopher Fletcher

ENTRY #4

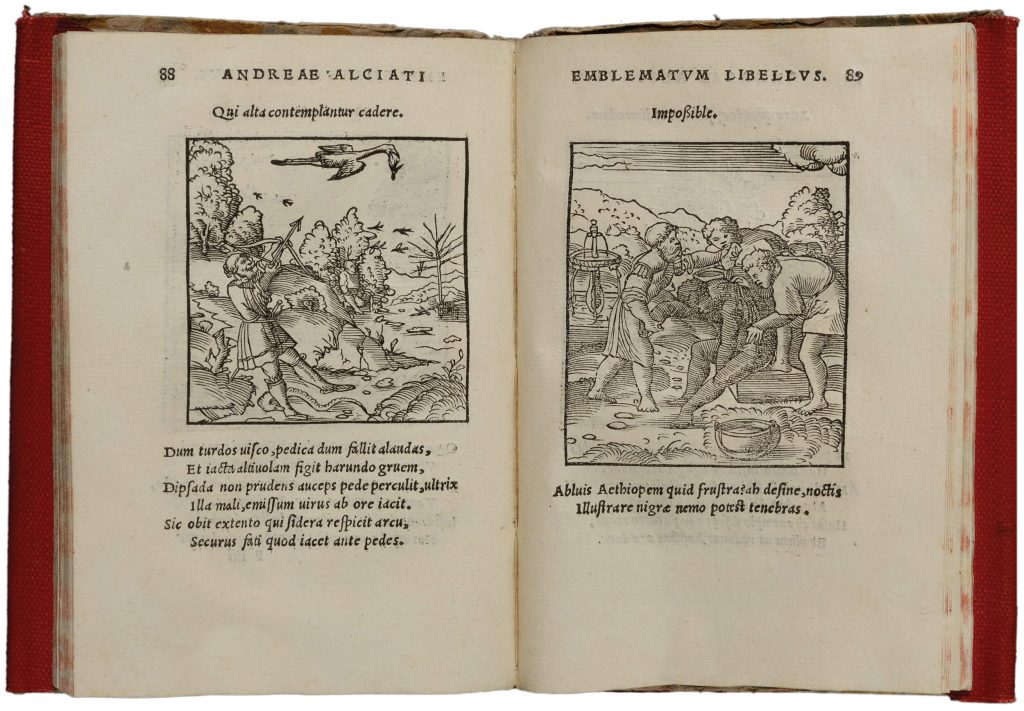

A. Andrea Alciato (1492–1550), author; Jollat(?), artist

Andreae Alciati Emblematum libellus, 1536

Book with letterpress and woodcuts

Case W 1025 .0165

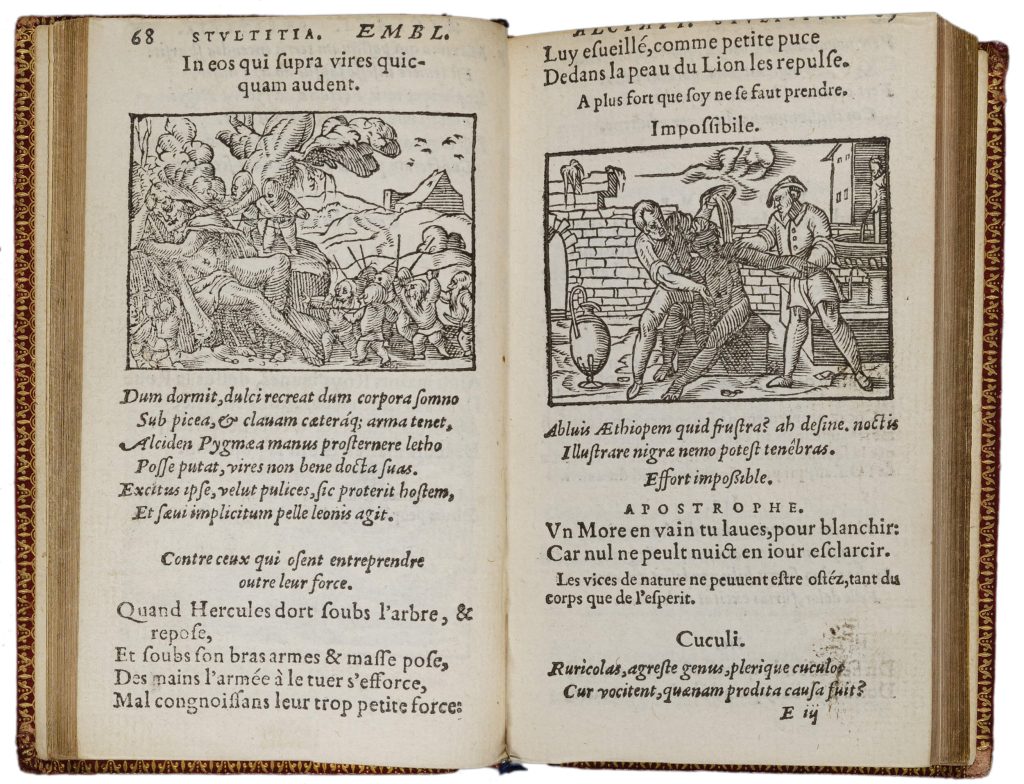

B. Andrea Alciato (1492–1550), author; Barthélemy Aneau (c. 1510–1561), translator and commentator

Emblèmes d’Alciat: en latin et françois vers pour vers: ordonnez en lieux communs auec briefues expositions et figures propres: auec la table d’iceux, mise à la fin, 1561

Book with letterpress and engravings

Wing ZP 539 .M3675

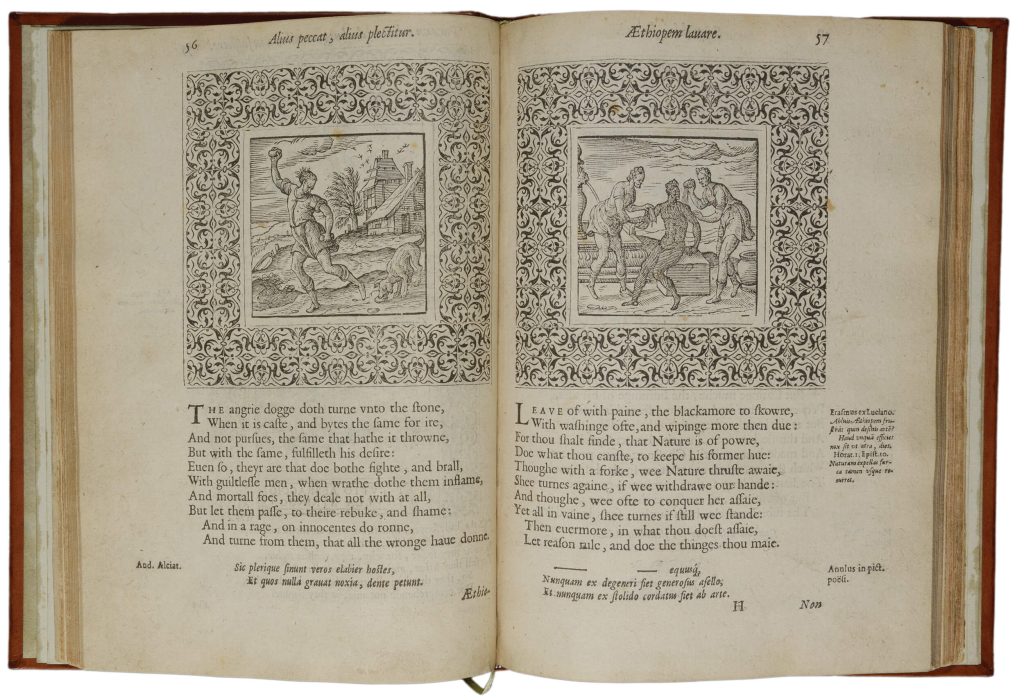

C. George Whitney (1548?–1601?), author

A Choice of Emblemes and other Devises, for the Moste Parte Gathered Out of Sundrie Writers, Englished and Moralized, 1586

Book with letterpress and engravings

Case W 1025 .0165

Emblems were one of the most significant sites for early modern Europeans to think through visual culture. By the middle of the sixteenth century, authors and artists deployed them in a variety of visual media — books, public monuments, household objects, and so on — in order to provide entertainment and instruction for their readers in a range of topics, from religion to politics to primary education. In all these formats, emblems functioned as literary-visual puzzles that consisted of a titular inscription (motto), an image (pictura), and a short text (subscriptio), which was usually an epigram. Viewers, often working together in groups, used the different elements of the emblem to interpret and comment on the others in order to decipher or invent some kind of lesson or truth that would help them understand the natural world, human behavior, religious truth, and how all should properly work. In this, emblems played an important role in how European audiences made sense of the rapidly expanding and diversifying world in the sixteenth century. Naturally, then, audiences throughout Europe also used emblems to think about race, which was becoming ever more visually present in their daily lives.

Emblems functioned as another way to implicitly or explicitly categorize physical differences between peoples. One of the clearest examples of this was an emblem depicting the fruitless effort to wash the blackness out of an Ethiopian man, shown here in three different emblem books produced between 1536 and 1586. All three use this image to illustrate an impossible task, thus reinforcing the notion that skin color, as it is a product of “Nature,” could be used to sharply delineate one people from another. Although the emblem could be used to consider an endless variety of impossible tasks or irreconcilable differences in nearly endless contexts, this particular pictura — which appeared in hundreds of emblem books throughout Europe — also served to reinforce the hardening power dynamics between white-skinned Europeans and Black Africans, who were, at the very same time, being enslaved to work in European colonies in ever-growing numbers. The three emblem books considered here, for example, would have first reached audiences in France and England, at a time when colonial aspirations were just becoming economic and political priorities for each kingdom. Within this context, white French and English readers could hardly have missed the “truth” of European supremacy expressed by the image of fully clothed

white men forcibly washing the skin of a naked Black man, who seems, in all three cases, resigned to his fate. In this, the emblematic treatment of “washing the Ethiopian white” confirmed the assumed primacy of white Europeans in the new world order, demonstrating how, even when solving puzzles with friends for their own entertainment, Europeans were constantly reminded of their fantasized racial dominance.

Further Readings

Daly, Peter M. The Emblem in Early Modern Europe: Contributions to the Theory of the Emblem. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Manning, John. The Emblem. London: Reaktion, 2002.

Spicer, Joaneath, ed. Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe. Baltimore: Walters Art Museum, 2012, 126. Exhibition catalog.[60]

Christopher Fletcher

ENTRY #5

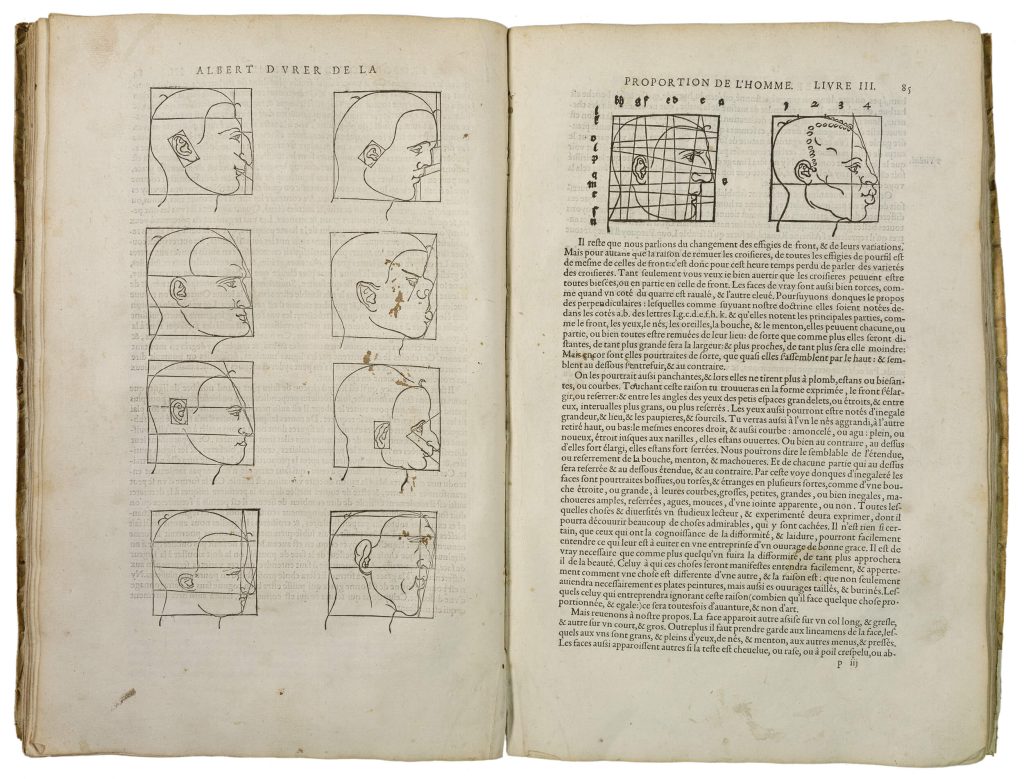

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), author; Charles Perier, Publisher

Les Qvatre livres d’Albert Dvrer, peinctre & geometrien tres excellent, de la proportion des parties & pourtraicts des corps humains (The Four Books on Human Proportion), 1557

Book with letterpress and woodcuts

Wing folio ZP 539.P412

Albrecht Dürer intended the Four Books on Human Proportion to aid artists in drawing human figures. The text defines several ideal types of human physiognomy based on the measurements and proportions of different limbs described in classical sources. It then explains how artists can apply mathematical projections to alter these types and generate varied, imagined, human forms like the profiles shown here at left. Dürer also envisioned this system as a means of comparing real, observed physiognomies to these ideal types, believing that deviations from the ideal were linked to a person’s race and character. At right, the profile drawn with curly hair compares a Black African sitter drawn from life to an “ideal” profile with particular attention to the sitter’s nose. Elsewhere in this text Dürer claimed that African faces, and especially noses, were less “handsome” than Europeans’.

While Dürer’s system is ungainly — some sixteenth-century users complained that it was difficult to apply in practice — in this edition, stains splashed on the page at left, may attest to this text’s use. The Four Books on Human Proportion ultimately became widely[61] popular. First published in German in 1528, the book was translated into five languages, and issued in more than 15 different editions over the subsequent 125 years, including three (French, Italian, and German) in the Newberry collection alone. The work’s popularity speaks to the appeal in the early modern period of the possibility, whether theoretical or applied, of quantifying human difference on the basis of the repeatable interpretation of visible signifiers.

Further Readings

Koerner, Leo Joseph. “The Epiphany of the Black Magus circa 1500.” In The Image of the Black in Western Art, edited by David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, 3:7–92. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010, 86–89.

Smith, Jeffrey Chipps. Dürer. London: Phaidon Press, 2012, 365–69.

Spicer, Joaneath, ed. Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe. Baltimore: The Walters Art Museum, 2012, 46. Exhibition catalog.[62]

Olivia Dill

Entry #6

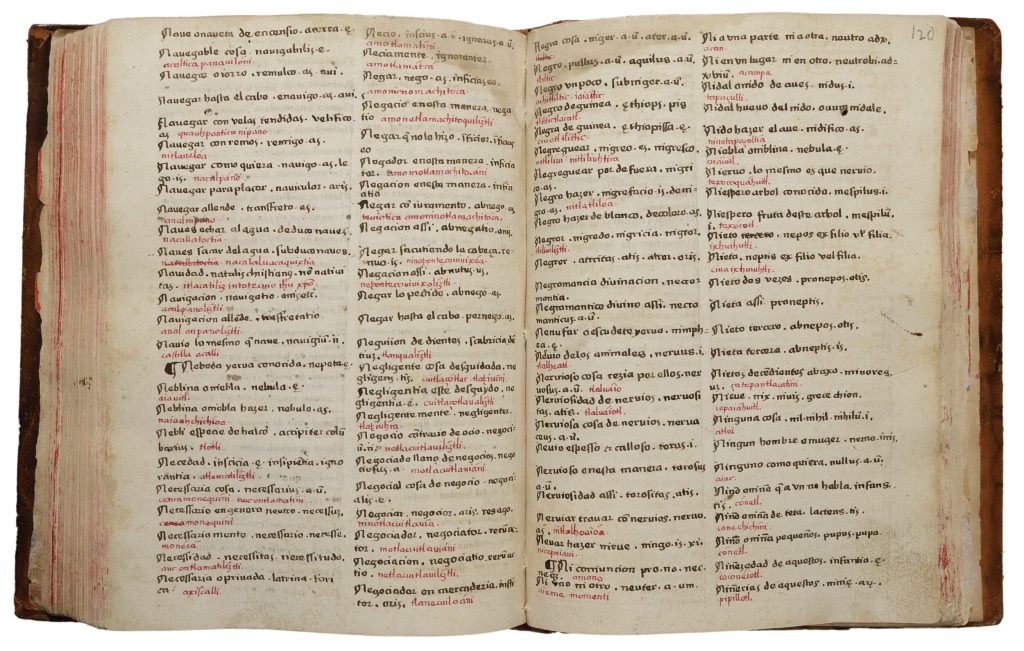

Antonio de Nebrija (1444?–1522), author; Anonymous, transcriber

“Negreguear” entry, in Dictionarium ex Hisniensi in Latinum sermonem

(also known as Vocabulario trilingüe, that is, Trilingual Vocabulary), 1540

Manuscript VAULT Ayer MS 1478

Antonio de Nebrija’s reputation as an authority on vernacular languages was solidified after he systematized Castilian grammar with a treatise in 1492 and debuted a Spanish-Latin dictionary three years later. The Newberry’s Dictionarium ex Hisniensi in Latinum sermonem (1540) is attributed to him as well, since its trilingual body, composed of Latin, Spanish, and manuscript Nahuatl (one of the native languages of modern-day Mexico), is largely based on his dictionary’s second edition (1516). Several subsequent versions of this early pair were printed in Salamanca and Seville respectively and circulated throughout New Spain, the East Indies, and elsewhere in Europe, as imperial lexicographical templates from the sixteenth century onward.

The anonymous scholar who copied by hand entries from Nebrija’s printed bilingual dictionary in this manuscript is believed to have been an Indigenous person fluent in Nahuatl. Presumably writing for a Nahua audience, the scribe augmented more than 70 percent of the original Spanish-Latin entries in black ink with nearly 12,000 Nahuatl translations just below them in red ink. The resulting modified manuscript of Ayer 1478 is also comprised of idioms and lengthier explanations for incommensurable terms, including religiously inflected vocabulary predicated on Christian worldviews. The appearance of “negreguear” alongside “nigreo” — meaning “to blacken” or “become black” in Spanish and Latin — within its pages signals the confluence of cosmological, chromatic, and racial import. It further gestures towards the occulted role that Black African –derived people would come to play in seemingly bipartisan debates around settler-native encounters in the New World. Though not accompanied by a third translation, the Nahuatl cognate for black “tlíltic” is listed above this entry in the same column.

Further Readings

Clayton, Mary L. “Evidence for a Native-Speaking Nahuatl Author in the Ayer Vocabulario Trilingüe.” International Journal of Lexicography 16, no. 2 (2003), 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/16.2.99.

Wynter, Sylvia. “1492: A New World View.” In Race, Discourse, and the Origin of the Americas: A New World View, edited by Vera Lawrence Hyatt and Rex Nettleford, 1–57. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution press, 1995.[63]

Cecilio M. Cooper

Entry #7

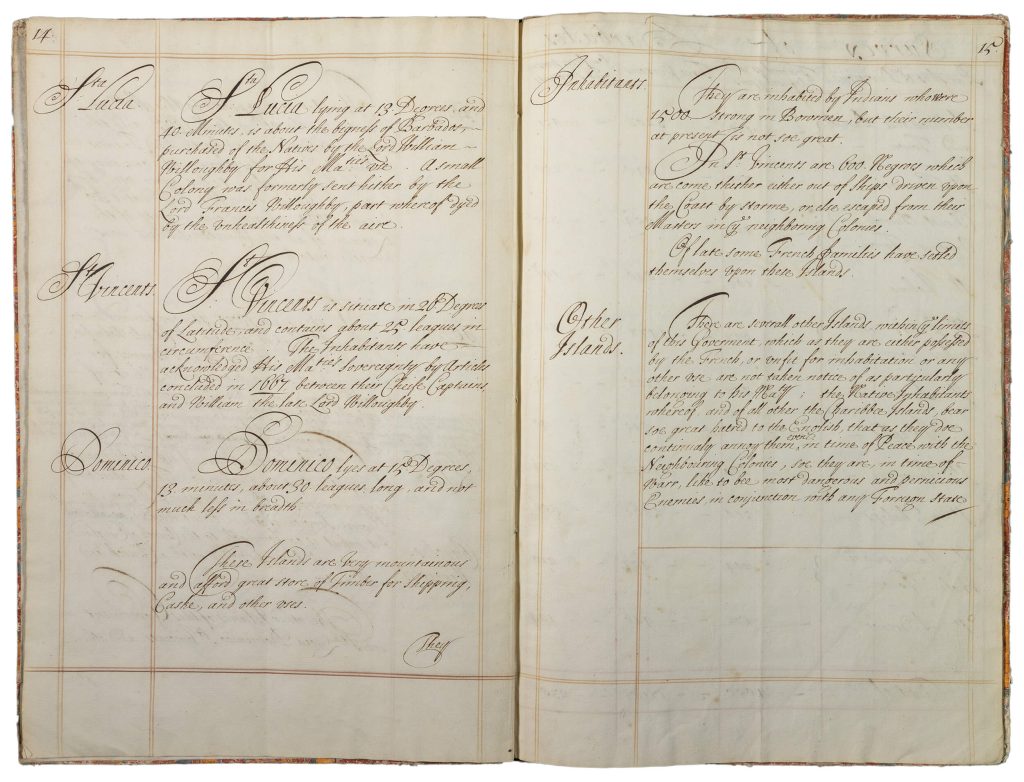

William Blathwayt (1649–1717), Secretary for Trade and Plantations (1675–1679)

The Short State of Barbados and the Government Thereof: A Remarkably Interesting Manuscript, 1638

Ayer MS 827

This document from 1684 features in the collection of William Blathwayt, who served as assistant secretary of trade and plantations of England from 1675 until he was promoted to full secretary in 1679. The manuscript, whose scribe is unknown, begins with a narrative section logging the “situation,” “extent,” and “discovery” of the island of Barbados, which the author notes was “found uninhabited and very fit for a plantation” and then documents the English’s role in creating and maintaining foundational legal structures to govern the institution of slavery, with slave law codification occurring in Barbados in 1661 and 1688. The document makes clear that Barbadians made racialized distinctions between those who would be indentured for life, and those who would serve under contract. Inhabitants were sorted into four different categories: “Freeholders, “Freemen,” “Servants,” and “Slaves.” While the former three sorts contain no mention of race, “Slaves” are described specifically as “the Negros brought thither from the coast of Guiny, Cormantine [?], and Madagascar, who live as slaves to their Mastirs.”

The population census is divided into “Whites” and “Blacks” with totals of 19,566 and 66,070 respectively. The document refers to the “acquisition” of “St. Lucia, Dominico, St. Vincents, and others,” with “St. Vincents” being inhabited by “Negroes which are come thither either out of Ships driven upon the Coast by stormes, or else escaped from their Masters in neighboring Colonies.” It is noted that there are several islands which are “uninhabitable” due to the “Native Inhabitants” who “bear soe great hatred to the English, that as they doe continualy annoy them, even in time of Peace with the Neighbouring Colonies.” This manuscript largely logs statistical, governmental, and geographic particulars, but the contents additionally offer a narrative of Black and Indigenous resistance to colonization, the author noting that the “Native Inhabitants” are “like to bee most dangerous and pernicious Enemies,” and especially so “in conjunction with any Foreign State.”

Further Readings

Pettigrew, William A. “Free to Enslave: Politics and the Escalation of Britain’s Transatlantic Slave Trade, 1688–1714.” The William and Mary Quarterly 64, no. 1 (2007): 3–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4491595.

Rugemer, Edward B. “The Development of Mastery and Race in the Comprehensive Slave Codes of the Greater Caribbean during the Seventeenth Century.” The William and Mary Quarterly 70, no. 3 (2013): 429–58. https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.70.3.0429.[65]

Alana Edmondson

Case Study #2: Gendering Race (Women, Race, Aesthetics)

Entry #8

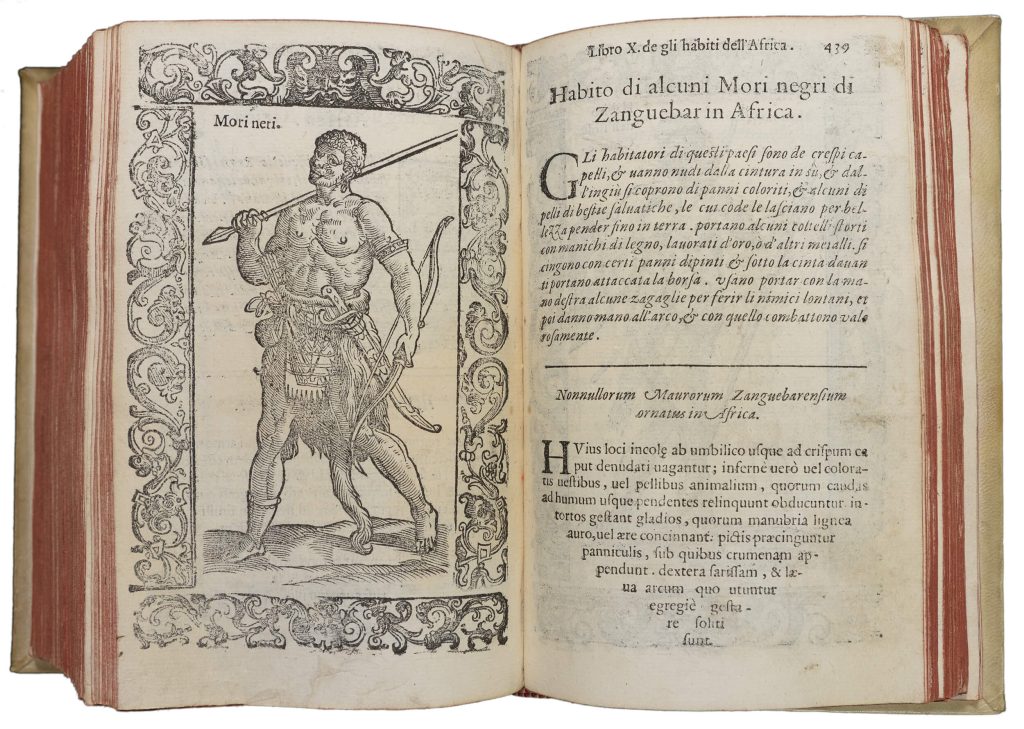

Cesare Vecellio (approx. 1521–1601), author; Christoph Chrieger (active sixteenth century), artist of woodcuts (based on Vecellio’s drawings); Sulstatius Gratilianus (active sixteenth century), translator (Italian texts into Latin)

Habiti antichi et moderni di tutto il mondo—Vestitus antiquorum recentiorumque totius orbis (Of Costumes, Ancient and Modern, of Different Parts of the World), 1598

(second edition; first edition was published in 1590)

Book with letterpress and woodcuts

Vault Ayer 335.V3 1598

Cesare Vecellio’s costume book Habiti antichi e moderni (1598) offers an encyclopedic and partly historical treatment of dress. The images are organized hierarchically by continent: European dress takes up the bulk of the book, followed by sections on Asian, African, and American dress. Dress was one dimension of “habit,” which in the early modern period referred to the web of customs, manners, and morals that distinguished various cultures. However, the wide circulation of Vecellio’s costume books across Europe did more than mark cultural difference: his images of dress also helped construct notions of racial difference.

Vecellio’s information about European dress came in part from first-hand encounters in cosmopolitan Venice, but most of his information about Asian, African, and American dress was drawn from secondary sources, such as Theodor de Bry’s Les Grands Voyages (1590). The depiction of an Indigenous Floridian woman in “Clothing of a Queen” was modeled on a similar image from de Bry. Standing decontextualized from her social and natural surroundings, the woman is positioned as an Eve-like figure. Her partial nudity starkly contrasts with the elaborate, historically contextualized dress of Venetian nobility.

In the section on African dress, Vecellio features more images of men than women. His depictions of African men, such as “The Black Moor from Zanzibar,” often feature darkly shaded skin and exaggerated facial features, accompanied by negative commentary. In contrast, his few depictions of African women emphasize their dress rather than physiognomic difference. The lack of representation of Black women raises questions about the gendered nature of early modern racial prejudice. Asian cultures occupy a higher position in Vecellio’s continental hierarchy: for instance, he accurately included the Persian terms used for their job titles and garments of the Ottoman Sultan’s Persian staff bearers. While Vecellio sometimes depicted foreign dress with nuance and cultural sensitivity, Habiti antichi e moderni nevertheless helped solidify negative racial stereotypes that were used to justify European colonial projects.

Further Readings

Jones, Ann Rosalind. “Cesare Vecellio’s Floridians in the Venetian Book Market: Beautiful Imports.” In The Discovery of the New World in Early Modern Italy: 1492–1750, edited by Elizabeth Hodorowich and Lia Markey, 248–269. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Jones, Ann Rosalind, and Margaret F. Rosenthal. Cesare Vecellio’s Habiti Antichi et Moderni: The Clothing of the Renaissance World. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2008.

Paulicelli, Eugenia. “Mapping the World: The Political Geography of Dress in Cesare Vecellio’s Costume Books.” The Italianist 28, no. 1 (2008): 24–53. https://doi.org/10.1179/ita.2008.28.1.24.[68]

Melani Shahin

Entry #9

Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1563–1611) and Bernard Paludanus (1550–1663), authors

Johannes van Doetecum (1530–1605), engraver

Sati Ritual in Itinerario, voyage ofte schipvaert (Discourse of Voyages into the East & West Indies), 1596

Book with letterpress and engravings

VAULT Ayer 124 .D91 L7 1596

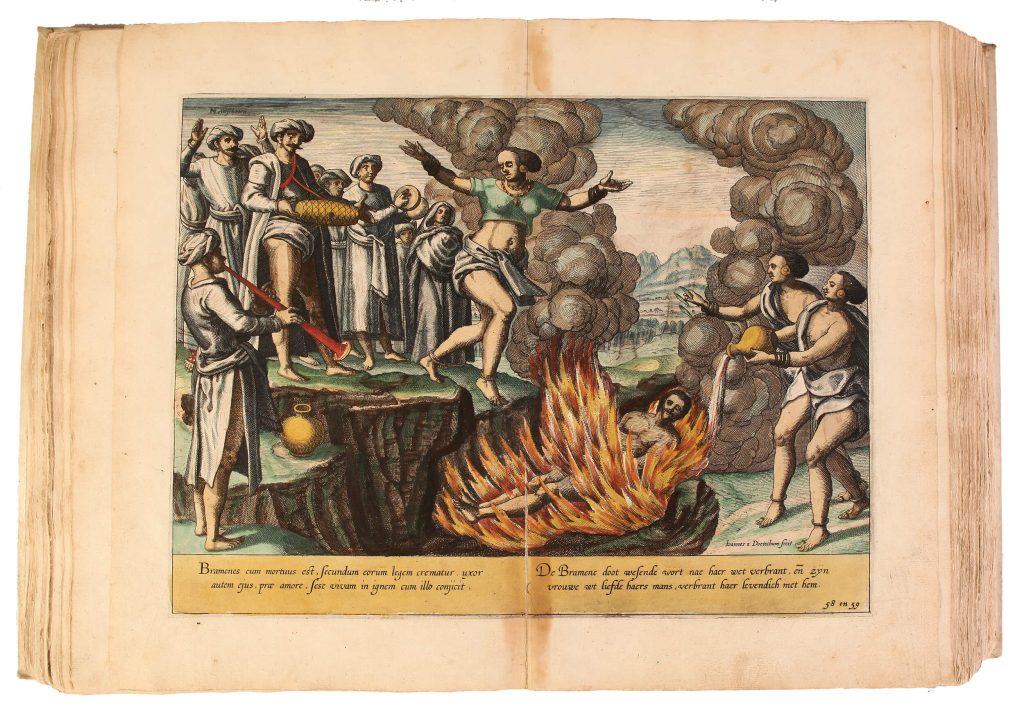

*This image is from a 1596 edition at the John Carter Brown Library, R 1-SIZE F596 .L759i

The 1596 publication of Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s Itinerario was a watershed in the history of European colonialism. The Itinerario contained classified information collected during Linschoten’s time working for the Portuguese in Goa that allowed the Dutch to disrupt Portuguese domination over trade with East and South-East Asia. Accompanying the text were 36 engraved illustrations of the peoples, customs, and topography of India that Linschoten claimed were drawn from life and could thus be understood by the contemporary audience as empirical content.

One illustration depicts the Hindu ritual of sati, in which widows sacrifice themselves through self-immolation. In the center of the image, the widow jumps with arms outstretched into her husband’s funeral pyre. Between 1500–1800, Europeans frequently reported on the ritual, but the ethnographic accuracy of these accounts is questionable since sati was rarely practiced in early modern India. Moreover, descriptions of sati found in sources like the Itinerario often followed formulaic narratives.

Of the sati practice, Linschoten provides two explanations: first, that the wives perform this act as a sign of marital devotion; second, that the tradition began as a way to police the “wickedness” of Indian women who allegedly poisoned their husbands. In Linschoten’s engraving, the dangerousness of the non-European female body is disciplined by ritualistic death, carefully observed by the audience of men — both inside and outside the image — who surveil her body throughout the sacrifice. The woman is laden with jewelry and clothed only in a loincloth, prominently displaying her breasts and her exotic, sexual, and material excess. Linschoten, who heavily criticized racial miscegenation in his text, subdues the figure of the Indian woman by visually distancing her from European propriety all while flaunting her body to the European readers.

Further Readings

Banerjee, Pompa. Burning Women: Widows, Witches, and Early Modern European Travelers in India. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Celso de Castro Alves, José. “Rupture and Continuity in Colonial Discourses: The Racialized Representation of Portuguese Goa in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.” Portuguese Studies 16 (2000): 148–161. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41105143.

van den Boogaart, Ernst. Civil and Corrupt Asia: Image and Text in the Itinerario and the Icones of Jan Huygen van Linschoten. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.[69]

Arianna Ray and Melani Shahin

Entry #10

Francis Delaram (1590?–1627?), engraver; George Sandys (1578–1644), author

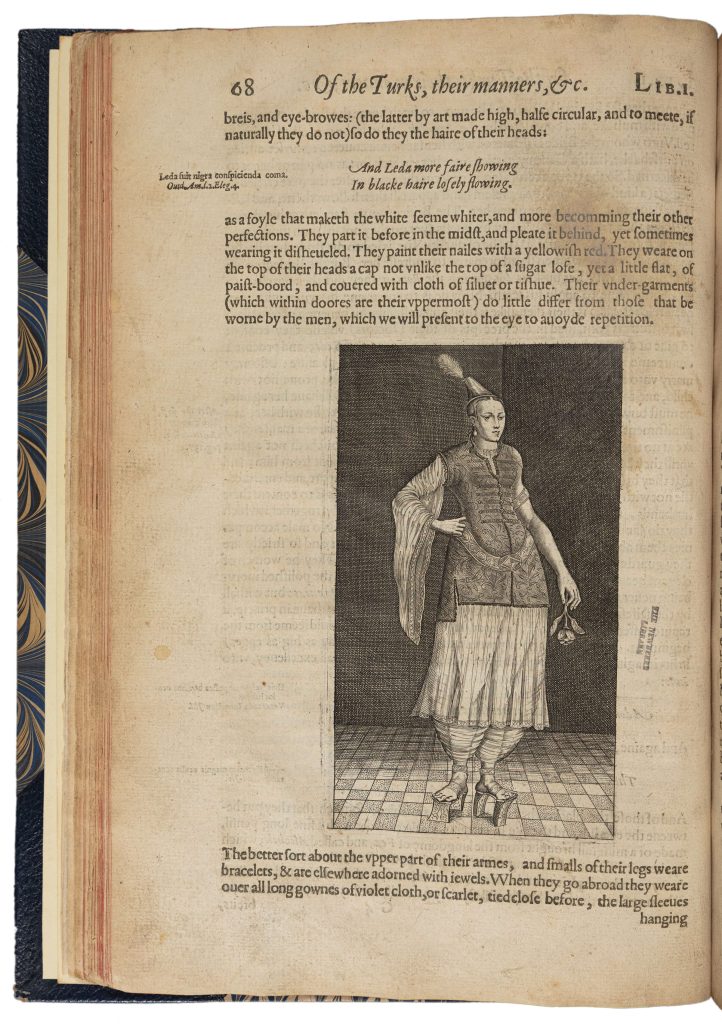

“An Ottoman Lady” in A relation of a iourney begun an. Dom. 1610: foure bookes, containing a description of the Turkish Empire of Aegypt, of the Holy Land, of the remote parts of Italy and ilands adioyning, 1615

Book with letterpress and engravings

Case Folio G 29 .777

George Sandys published his influential Relation of a Journey in 1615. On p. 68, a relatively large engraving (3.2 × 5.5 inches) offers a full body portrait of an anonymous Ottoman woman, which supplements Sandys’s verbal description: “they be women of elegant beauties, for the most part ruddy, cleare and smoothe as polished ivory.” Sandys describes cosmetic practices and female hairstyles, as well as the under-garments which “within doors are their uppermost,” and which he decides to “present to the eye to avoide repetition.” Since neither Sandys nor his readers would have had access to the domestic spaces of Ottoman women, the image constitutes a scene of voyeurism, where readers get to see what they should not.

Mark the lower half of the woman’s outfit: while the lines on her skirt seem at first to be textile folds, the diaphanous quality of her right sleeve orients the reader’s gaze, suggesting that her skirt too might be diaphanous, and encouraging us to focus on the slightly bolder lines of that skirt, which actually reveal the shape of the woman’s legs through her skirt and fluid trousers. The image rewards an intrusive male gaze, granting English readers access to the Ottoman woman’s body and the license to engage in proto-Orientalist erotic fantasies. The juxtaposition of this softcore erotica with Sandys’s description (on the right page) of the veil that Muslim women wear outdoors “that no more is to be seene of theem then their eyes” makes the voyeuristic dimension of the image particularly salient.

Further Readings

Andrea, Bernadette. Lives of Girls and Women from the Islamic World in Early Modern British Literature and Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017.

Burton, Jonathan. Traffic and Turning: Islam and English Drama, 1579–1624. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2005.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.[72]

Noémie Ndiaye

Entry #11

Lady Mary Wroth (approx. 1587–1561/3)

The Countesse of Mountgomeries Urania, 1621

Book (folio) with letterpress and engraved frontispiece

Case folio Y 155 .W94

Mary Wroth’s The Countess of Montgomery’s Urania (1621) is a romance (proto-novel) with a collection of sonnets appended to the end. The sweeping narrative follows a core group of royal characters — vaguely based on real-life nobles at the British court of King James VI and I — who travel the world seeking adventure, surviving magical enchantments, and navigating complicated erotic entanglements. Its idealized international setting offers a convenient backdrop for exploring fantasies of race and foreign encounter. Indeed, Urania appears to respond directly to contemporary travelogues, atlases, and literature in which objects of colonial interest (land, resources, etc.) were conflated with erotically enticing female figures — that is, visibly “foreign” women whose desirability threatened a core element of European women’s already limited power.

If European men were advancing white supremacy as justification for colonization, then Wroth’s work shows European women had a vested interest in valorizing white femininity to maintain sexual power as their exposure to other cultures increased. Urania’s white heroines often encounter dark-featured antagonists whose sexuality endangers their relationships; in the sonnet cycle, Wroth’s speaker compares her pale complexion against “Indians scorch’d with the sun” to measure her own erotic devotion — an image that recalls Wroth’s documented experience performing at court in blackface as a “Daughter of Niger” who yearns to turn white in Ben Jonson’s Masque of Blackness (1605). By staging such scenarios repeatedly across the narrative and related poems, Wroth works to reinforce imaginatively the desirability and thus the socio-sexual power of white European women.

Further Readings

Andrea, Bernadette. “The Tartar Girl, the Persian Princess, and Early Modern English Women’s Authorship from Elizabeth I to Mary Wroth.” In Women Writing Back/Writing Women Back: Transnational Perspectives from the Late Middle Ages to the Dawn of the Modern Era, edited by Anke Gilleir, Alicia Montoya, and Suzan van Dijk, 255–281. Amsterdam: Brill, 2010.

Hall, Kim F. Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995.[73]

Rebecca L. Fall

Entry #12

Portrait of Pocahontas, 1793, reprint after Simon van de Passe (1595–1617), artist;

John Smith (1580–1631), author

Portrait of Pocahontas, from The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles, 1624.

Engraving

Ayer E99 .P85 M38 1793

This 1793 reprint after the 1616 engraving is the only known portrait from the life of Pocahontas, alias Matoaka or Rebecca Rolfe. The half-length oval portrait depicts Pocahontas in contemporary English dress: she wears a fitted gown with a high lace collar, an embroidered jacket, and a captain hat. Her jewelry and fan emphasize her noble status as an ambassador. The portrait’s Latinate frame names its subject as “Matoaka, alias Rebecca, daughter of the most powerful prince of the Powhatan Empire, in Virginia.”

Pocahontas’s engraved portrait was commissioned by the Virginia Company to publicize her 1616 goodwill tour of England. Wearing this costume, Pocahontas appeared before King James I alongside her husband, colonist John Rolfe. Her performance at court reassured the Crown of the safety of its investment in the Jamestown colony. Dressed in English fashion and using her Christian name of Rebecca Rolfe, Pocahontas embodied the potential assimilation of the Indigenous Powhatan Confederacy into a white, Christian, colonial society.

In 1624, after Pocahontas’s death, Captain John Smith reprinted her portrait in his bestselling memoir, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles. His fictionalized narrative inspired later depictions of a romance between Pocahontas and Smith himself. However, the 1616 portrait demonstrates that the historical Pocahontas appeared to her contemporary audience not as the stereotypical “Indian Princess,” whose image was constructed through contemporary travelogues, maps, and costume books, but as a well-dressed English lady. The conventions of her portrait enact the erasure of Pocahontas’s American Indian identity, which the Virginia Company replaced with an advertising image of the profitability of colonial investment. This 1793 reprint shows the enduring legacy of Pocahontas’s iconography into the late eighteenth century.

Further Readings

Ganteaume, Cécile R. Officially Indian: Symbols That Define the United States. Washington, DC: National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, 2017.

Townsend, Camilla. Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004.[76]

Julia Marsan

Entry #13

John Bulwer (1606–1656), author; William Hunt (1647–1660), printer

Anthropometamorphosis: man transform’d; or The artificiall changling, 1653

Book with letterpress and woodcuts

Case F 03.13

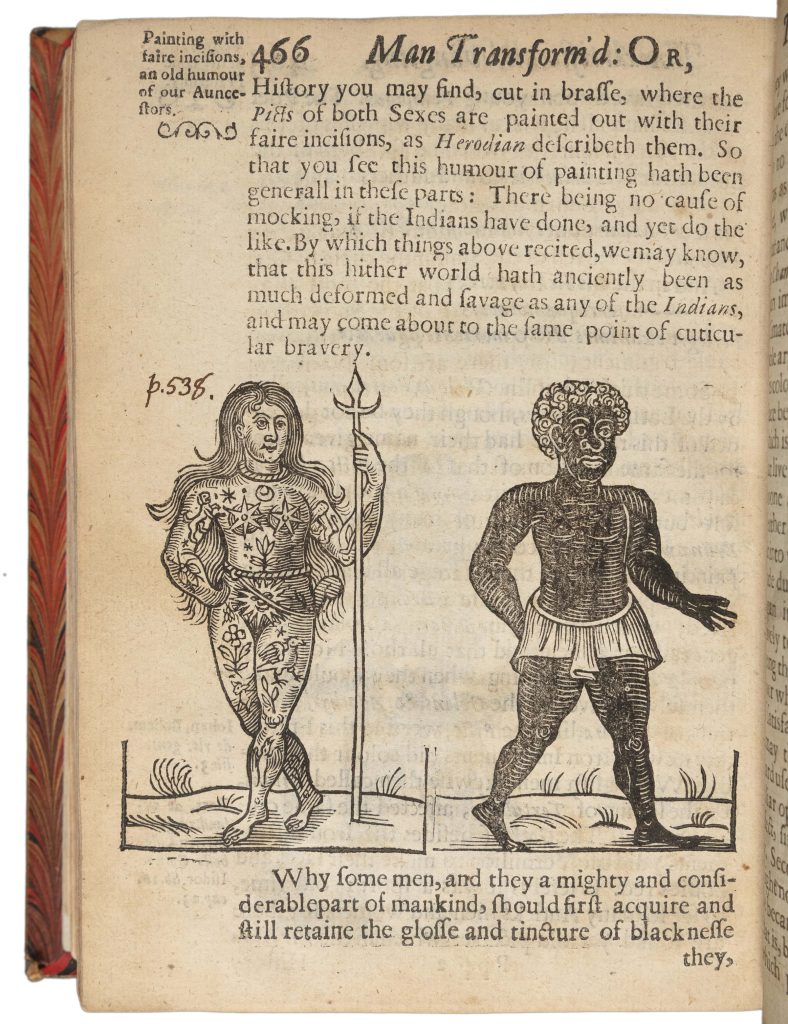

John Bulwer was an English physician whose encyclopedic Anthropometamorphosis (1653), divulges an ethnology of complicated racial and ethnic markers among various nations. Including woodcuts representing the modification of human body parts, Bulwer identified various artificial transformations among people from all around the world. He believed that all humans were malleable at birth, and that foreign customs involved voluntary transformations whereby men strayed from the image intended by God (on the book’s frontispiece, humans with various bodily mutilations face divine judgment while the Devil laughs). Artificial transformations include head shaping, tattoos, scarring, and more. These aligned closely with early modern ideas of monstrosity, as Bulwer features mythological beings (e.g., humans with dog heads from the ancient region of Scythia) alongside recognizable racial and ethnic groups (e.g., Mexicans, Russians, Americans, Turks, etc.). Bulwer often centers the English body as representative of normativity and Nature, while aligning foreign nations with the unnatural and the monstrous, based on second-hand information derived from travel details and fictional tales.

In Scene 24, Bulwer describes tattoo practices and inquires into how populations “became Black”: the passage is accompanied by a woodcut representing a man of dark complexion wearing a white cloth around his loins. Bulwer offers several explanations for why the “seeds of Adam” may have black skin tones, such as the heat from the Sun, a curse of God, or the “inward use of certain waters.” Finally, Bulwer suggests that the “Moors” changed their complexions “into a new and more fashionable hue” because they were affected by the “beauty of blacknesse” and saw whiteness as the Devil’s hue. Said Black complexion, “first by art acquired,” eventually resulted in the reproduction of generations of similar racially identifiable individuals.

Further Readings

Campbell, Mary Baine. “Anthropometamorphosis: Manners, Customs, Fashions, and Monsters.” In Wonder & Science: Imagining Worlds in Early Modern Europe, 225–256. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Hall, Kim F. Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995.

Poitevin, Kimberly. “Inventing Whiteness: Cosmetics, Race, and Women in Early Modern England.” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 11, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2011): 59–89. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23242188.[78]

Aylin Corona

Entry #14

Miso-Spilus, seventeenth-century author

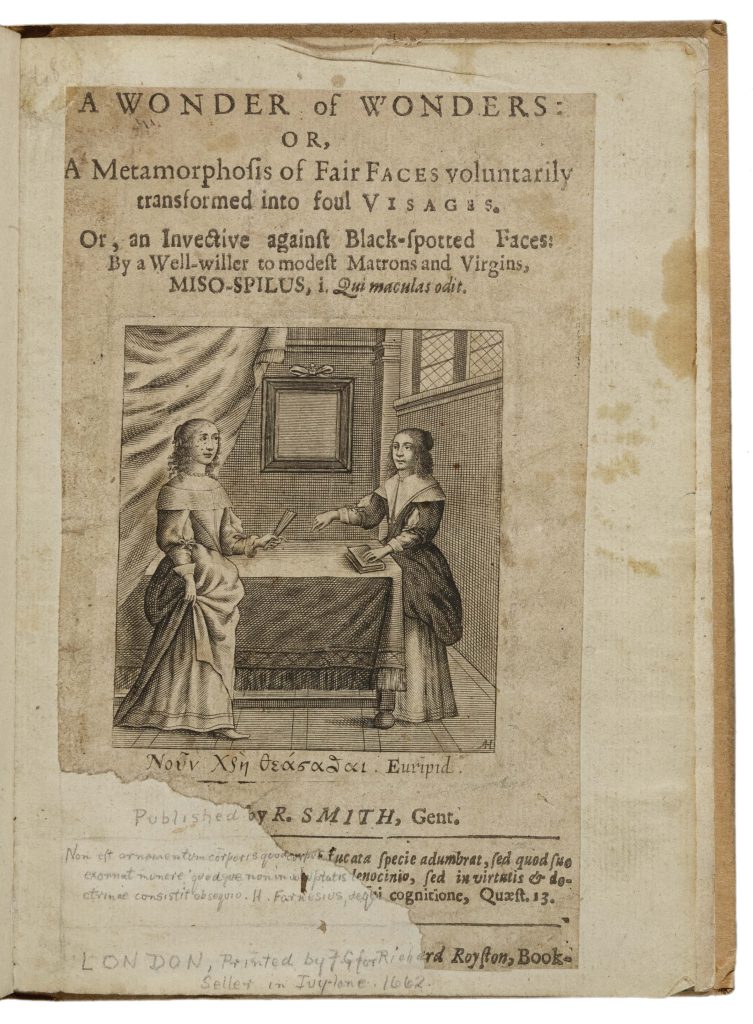

A wonder of wonders, or A metamorphosis of fair faces voluntarily transformed into foul visages: or, an invective against black-spotted faces, 1662

Printed pamphlet with engraved title page

Case K 73 .98

A printed pamphlet of 39 pages (including prefatory material and frontispiece), A Wonder of Wonders (1662) directly engages debates about cosmetics, female beauty standards, and anxieties about racial purity in seventeenth-century England. Authored under the pseudonym Miso-Spilus, Latin for “I hate spots,” the pamphlet sets forth an extensively annotated argument against women’s use of cosmetics — black beauty spots in particular.

Cosmetics in general played a key role in establishing racialized beauty standards in England, especially among women, by reinforcing “long standing associations of beauty and whiteness” and solidifying the relationship between those standards and English ethno-cultural supremacy. Yet even while cosmetics enabled women to perform whiteness more conscientiously, they also exposed complexion as an “unreliable marker of race” because it could be altered artificially. Cosmetics therefore became a flashpoint for anxieties about racial purity.

Miso-Spilus’s focus on black beauty spots explicitly connects white beauty standards to social prohibitions against interracial sex. The prefatory poem shown here, attributed to E. Westfield, claims beauty spots make women appear mixed-race: “From Britains and from Negroes sprung.” The immediately preceding lines, not shown here, further suggest that these anxieties go deeper than appearance: “Complexion speaks you Mungrels, and your Blood / Part Europe, part America, mixt brood.” These lines suggest that white beauty standards functioned in part as a bulwark against the perceived threat of miscegenation — proof not only of aesthetic superiority but also of blood purity.

Further Readings

Karim-Cooper, Farah. Cosmetics in Shakespearean and Renaissance Drama. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006.

Loomba, Ania, and Jonathan Burton, eds. Race in Early Modern England: A Documentary Companion. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2007.

Poitevin, Kimberly. “Inventing Whiteness: Cosmetics, Race, and Women in Early Modern England.” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 11.1 (2011): 59–89. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23242188.[79]

Rebecca L. Fall

animal skin dressed and prepared for writing, painting, or bookbinding

painted embellishment on a manuscript that often includes gold or silver

large book printed on paper sheets that were folded only once (by contrast with a quarto). Also refers to a single page in such a book

technique that uses only one color (gray) to produce an effect of depth

person who is not Jewish

genre of marvelous verse or prose narrative popular in premodern Europe, often but not always centered around a knight’s quest

text printed using relief printing

refers to the dimension of things that we apprehend through experience

concise and witty poem with a satirical edge

quality of a language or dialect native to the people who speak it (rather than a literate or foreign language)

relative to lexicography, the art or practice of writing dictionaries

relative to cosmology, which studies the universe as a whole, at the intersection of astronomy and metaphysics

subjected to indenture, the contract by which a person bound themselves to serve a master for a limited amount of time in the premodern world

transparent, see-through

cultural anthropology, the methods of which yield ethnographic scholarship

quality of being the norm