Back Bending Labor, Savage Dances, Pious Stances: Race in Motion between Africa and the Americas

Elena FitzPatrick Sifford and Cécile Fromont

[Print edition page number: 161]

Skin color — its origins, variations, stability across time and generations — has been a preeminent locus for reckonings over racial formation in European visual and material culture of the early modern period, alongside religion and genealogy.[1] Humoralism inherited from those whom Europeans called the Ancients posited a connection between geography and the nature of human bodies reflected in their complexion, of which skin color formed a most visible part.[2] Another set of distinguishing features, with an equally long history also arching back to European Antiquity and central to early modern understanding of difference and formulation of race, was that of civility and its outward manifestations in[162] comportment. Aristotle (384–322 BCE), Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274 CE), and their early modern era readers, historian Surekha Davies reminds us, saw an observable hierarchy between civilized and uncivilized, which material traces could be observed in mores and customs at the level of societies, but also in behavior at the level of the individuals.[3] “Strange gestures” were the marks of the savage, the witch, the idolater, and featured in early modern European visual culture as motifs, emblems, and iconographic markers of social, cultural, religious, and eventually racial otherness.[4] Further, in counterpoint to these depictions of heathens and “savages” and their “strange gestures,” early modern images of European catechization around the Atlantic world suggested the success of proselytism in the representation of converted Africans and Indigenous individuals in bodily attitude suggesting pious demeanor in Europe’s visual vocabulary, i.e. kneeling and hands joined in prayer.

This chapter considers a range of images conceived by Europeans in their attempts at making sense of difference and ascribing significance to social and cultural diversity in the context of their ambitions to colonize the Americas and Africa in the early modern period. Foremost in this process was the formulation and systematization of ideas of hierarchized difference that underlie conceptualizations of race. Visually and conceptually, racialization depended on identifying a set of visible markers to which meaning could be ascribed. Skin color, as well as other physical characteristics, would be the foremost signs of difference, but bodily comportment and motion also played an important role. In some examples, gesture, movement, and attitudes of the body could even supersede complexion and physiognomy as indicators of racial taxonomies. Racialized thinking penetrated deeper than outside visible appearance and attached its ideas to the body itself and its motion. The association of physical traits with bodily comportment played a central role in the circular logic of racial construction and its attempts at ascribing social significance to physical difference. Considering gestures and the meanings they encompassed as racial markers in early modern visual culture thus not only sheds light on the complex, multifaceted process of racial construction in European early modern thought, but also brings to the fore its ambiguities and contradictions and points to the centuries-long shadow these notions have cast over the circum-Atlantic world.

Back Bending Labor

Racial ideologies were not only perpetuated socially but became further systematized and normalized in the visual realm. Artists in the early modern Atlantic world utilized pigments, facial features, hairstyles, as well as ethnic clothing and accessories to visually mark figures as European, African, Indigenous, or any mixture thereof.[5] In addition to these details of skin color, dress (as discussed in this volume by Kaplan and Katz), and objects, the position of the body also served as a further racialized marker. Body posture and comportment were particularly important in Europe, a society that viewed the exterior body as revealing inner mind and character. Etiquette books and artists manuals from the period reveal the emphasis placed on bodily attitude.

Early modern scholars of rhetoric and the arts (oratory but also dancing and painting) discussed the connection between bodily temperament and quality of the mind, after Plato (c. 427–347 BCE) and[163] Quintilian (c. 35–100 CE): “The temper of the mind can be inferred from the glance and the gait.”[6] In turn, sixteenth-century Milanese choreographer Cesare Negri (c.1535–1605) outlined proper posture: “In order to go well above the body with that utmost grace and composure that others can honor means to go well with the body straight and the arms at the sides, moving them a little, and the toes of the feet a little out, so that the legs and the knees remain very straight, and in passing one foot ahead of the other.” He describes this posture as “gracious movement and beautiful good manners.”[7] In this view, upright positions denoted civility while bending or contorted bodies were considered wayward and lacking in composure.[8] This discourse also extended to social and economic status, the bending body attached to those of modest social and material conditions, of any race.

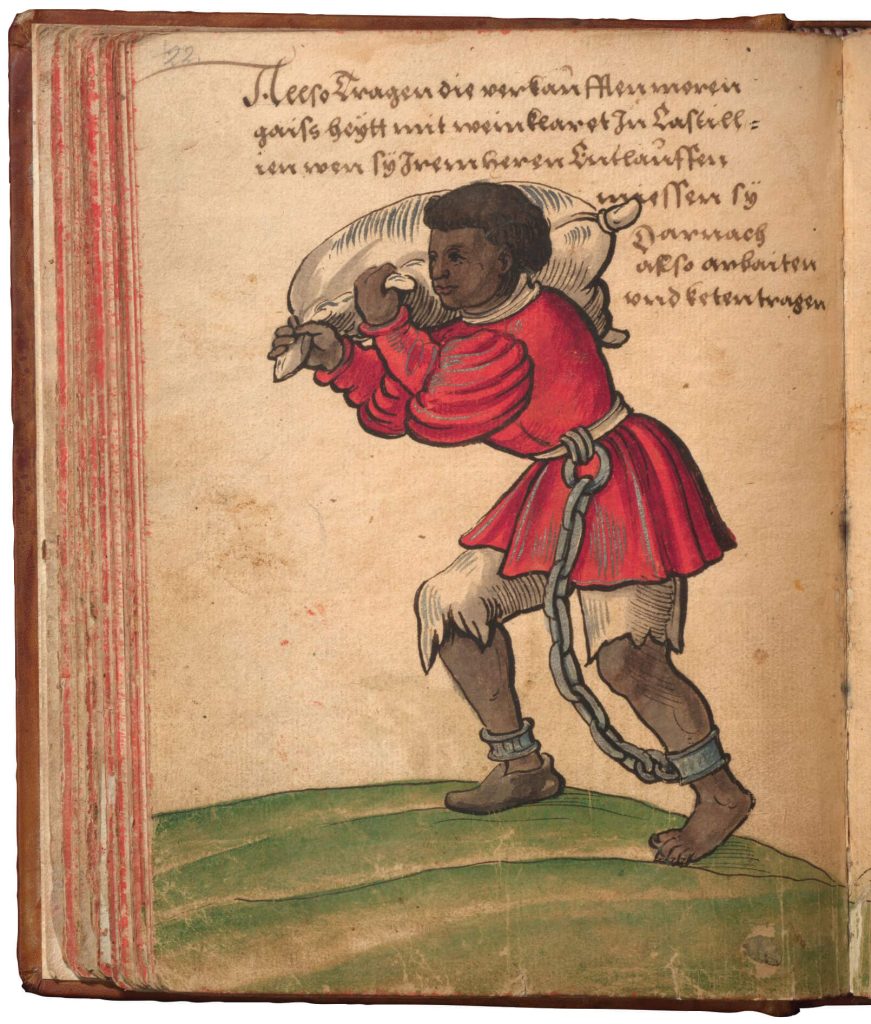

German artist Christoph Weiditz depicted such a slouched posture in his Trachtenbuch, a costume book produced during his 1529 travels in Spain (Figure 5.1). The inscription reads: “Negro slave with a wineskin in Castile: Thus the Moors who have been sold carry wine in goatskins in Castile; if they run away from their masters, they have to work thus and wear chains.”[9] The man in tattered clothing has shackles around the ankles, one chained and connected to his waist. Curiously, he wears just one shoe. As expected in a costume book, frayed clothing indicates the laborer’s status, but, notably, his bodily posture, paired with the profile view commonly associated with servility in early modern European iconography, equally communicates his servitude. A former runaway, the man is consigned to physically taxing work made all the more laborious by the chains constraining him, the humiliating and burdensome consequence of his foiled escape.

Christoph Weiditz, “African with a wineskin” in Trachtenbuch, 1529, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany

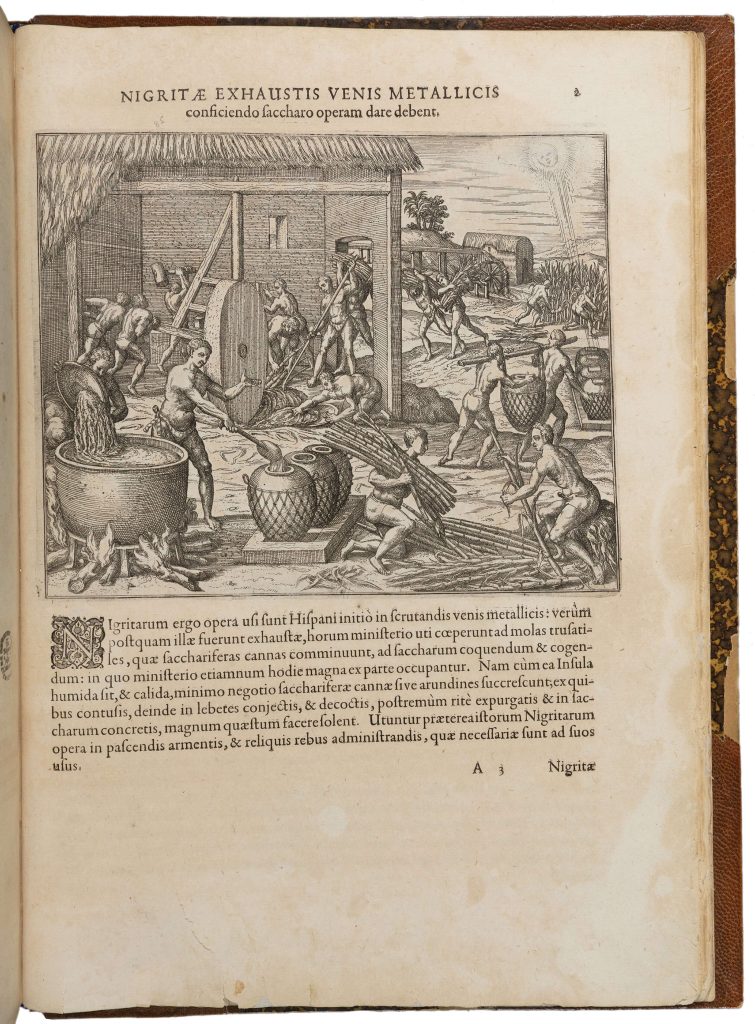

Bowed postures signifying servitude can also be seen crossing the Atlantic in one of the earliest images of New World slavery, an engraving featuring Africans processing sugarcane on the island of Hispañola (Figure 5.2). Though Theodor de Bry (1528–1598), a Protestant originally from the Spanish Netherlands, never set foot in the Americas himself, he executed twenty-seven volumes of woodcut prints based on accounts of various travelers, including three volumes of Milanese merchant-explorer Girolamo Benzoni’s (1519–1570) The History of the New World. One of the earliest images of African slavery in the Americas, it provides visual evidence of the transition from gold mining to sugar production on the Caribbean Island.[10]

Theodor de Bry, “Nigritae exhaustis venis metallicis consiciendo saccharo operam dare debent,” in America. Pt. 5, Frankfurt am Main, 1595, Newberry Library, VAULT Ayer 110 .B9 1590b v. 5

The enslaved in the engraving wear almost no clothes. Yet, rather than an erect classicizing posture of the heroic nude, the expected contemporary European depictions of the unclothed male, the bodies of the enslaved are shown bending, hauling, kneeling, and contorting. The focus of the image is on their toil at every step of the sugar production process. At the top right, figures begin the process by cutting the cane, the sun illustrated above beating down on their exposed backs. The cane is then bundled and carried[164] from the field to one of the two presses on the plantation, one a water mill in the distance, and the other, in the midground, human powered. These machines crushed the cane to extract their juice for further processing into crystalized sugar or molasses.[11]

Although the figures de Bry depicted are Africans, he represented them in the engraving without the heavy cross-hatching frequently used to denote dark skin. He did not figure their countenances either with rotund lips or flat noses following typical European stylizations of African features. Instead, the focus is on the figures’ bodies and postures to signify their status as laborers. Here the figures’ back bending toil within the Caribbean landscape, along with their lack of clothing and hunched postures, serve to identify them as enslaved Black Africans. The bent attitudes are what make clear to early modern viewers that the figures’ whole or near nakedness, far from Classical heroic nudity or Renaissance humanist idealization, is a sign of humiliation that marks them as “savage” and therefore suited to enslavement in the physically taxing Caribbean sugar mills.[165]

“Savage” Dances

Dance was an expressive genre equally important to Europeans, Indigenous Americans, and Africans in the early modern period as an activity of spiritual, political, and social significance. As Europeans confronted difference — real or imagined, at home or abroad — they took special note of choreographed, socially significant movement. Records of dance within rituals, entertainment, or pageantry, and often a combination of several of these, became a significant part of the colonial archive that Europeans strove to compile and interpret.[12] However, both documentations and interpretations met with the limitations of cross-cultural misunderstanding, willing or unwilling, and of the ideological nature of European descriptions and judgment of those they considered their “others.”[13]

In the early modern period, Europeans staged a range of performances that, through movement, costume, and choreography, both expressed and reinforced the conceptions of Otherness and racial difference they developed in support of their imperial and colonial ambitions. Balls, masks, processions featuring “savage” dress, movements, instruments, and choreographies formed foils against which Europeans systematized notions of racialized but also often religious difference. A foremost example in this regard is the broad tradition of Moors and Christians festival celebrations in which a danced battle featuring Catholics defeating infidels served a number of political purposes across Iberia and the lands in their sphere of direct control or indirect influence.[14] They presented the battle against Muslim opponents as a religious quest in a teleological narrative of the victory of Spaniards not only in the Reconquista of the Iberian peninsula, but against heathens anywhere. The triumph of Christians over Moors, for instance, became that of Spaniards over the Indigenous populations of the Americas.[15] In turn, the danced festival would find echoes in similar statements of victory and conquest outside of Europe, such as that of the Christian aristocracy of the Kongo who staged mock battles called sangamentos that strongly evoked the Moors and Christians dances they witnessed in their interactions with the Portuguese initiated at the end of the fifteenth century. Later, Africans and Afro-descendants living enslaved or free in the Americas and Europe found in the organization of events derived from sangamentos occasions to express social identity and exercise power, however limited, over their lived circumstances.[16] Related, non-Iberian early modern European courtly performances called morris, morisca, or moresque staged allegorical scenes including exotic characters, mocked combat, and dancing in circles with high leaps to the sound of percussion instruments.[17] Notably, Portuguese traveler Duarte Lopes (mid/late sixteenth century) and Italian cosmographer Filippo Pigafetta (1533–1604) used the term morescha in their 1591 Report of the Kingdom of Congo to[167] praise the dances the former had observed at the court of the great Christian king of Kongo.[18]

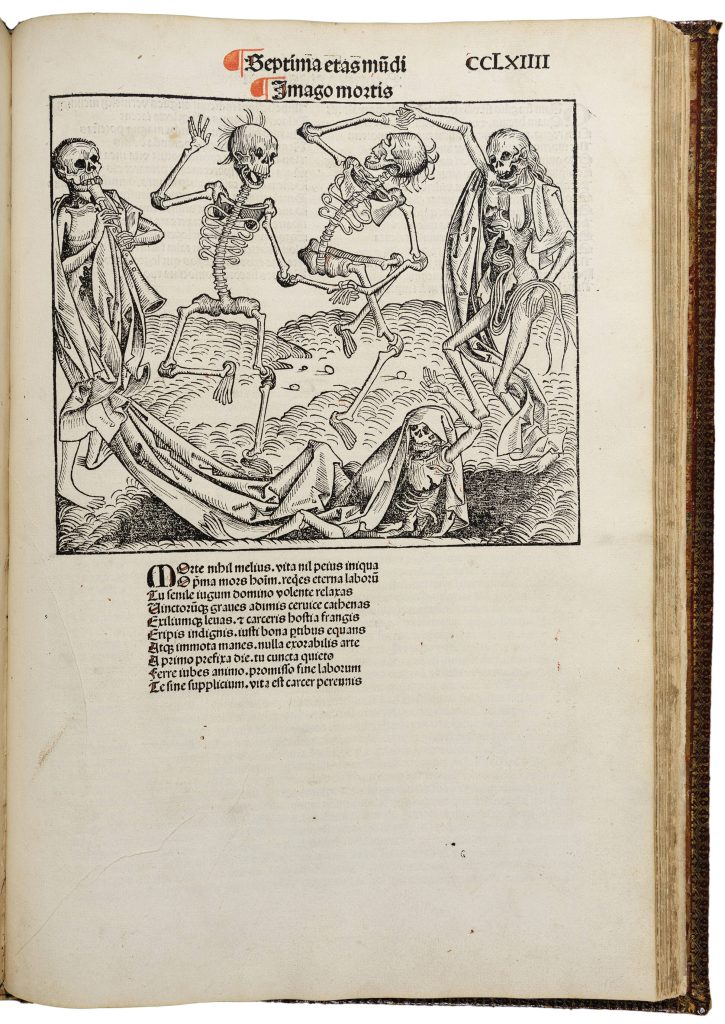

At a formal level, as already mentioned above, for early modern Europeans, bodies acted socially and their movements betrayed civility or lack thereof. Early modern European dance treaties described how performers “should be measured, moderated, always avoiding the extremes of excessive movement or too little movement.”[19] These ideals, expressed in Italian by the term misura, defined elegant, noble character, and gave visible form to virtue and ethical behavior. In contrast to the misura and civility of the courtly dancer, the late medieval visual and literary genre of the Dance of Death offered examples of unrestrained bodies in motion (Figure 5.3).[20] In vignettes from the genre, skeletal allegories of death leap and twirl around their victims in jerky, contorted moves, paying no heed to the dying’s social standing, age, or the purported morality of their societal role. Unrestrained gesturing of arms and legs, sardonic allusions to nudity from suggestively draped or tailored clothing revealing nothing but bare bones, give visual and gestural form to the wayward and ever looming threat of death and the social chaos it leaves in its wake. Arms above the head, legs folded and thrown to the back, the skeletal figures model gestures and attitudes unrestrained by social order. They are outrageous, excessive, immoderate, or, in the language of early modern Italian dance treaties, smisurati i.e. lacking misura. In this context, their excessive and transgressive movements have the purpose of delivering a moralizing message of memento mori, reminding all that they will inevitably die. Authors and illustrators of travel literature would turn to the same movements of the body in their depictions of Africans and Indigenous peoples, no longer as motifs of threatening, humorous sarcasm but as literal evocations of projected notions of lack of civility.

Michel Wolgemut, “Dance of Death” in Hartmann Schedel, Liber chronicarum. Nuremberg, 1493, Newberry Library, VAULT oversize Inc. 2084

Image-makers of the early modern period drew from the iconography of the Dance of Death in devising a visual vocabulary to portray dances and rituals among African and Indigenous populations they included as cartouches in maps, illustrations in printed travelogues, and motifs in artworks of all kinds. These representations were not ethnographic in that they did not attempt to record Indigenous or African comportment per se. Rather, they offered conventional representations of bodily movements that were considered to lack civility. In this regard, they ran parallel to the emblematic use of feathers as clothing and adornment to connote American origins in early modern images, regardless of the actual practices of the populations represented.[21] The high-stepping, arms-up stance the skeletons modeled would thus serve to illustrate a full range of peoples and activities that early modern Europeans homogenized as Other. The recourse to the Dance of Death not only inscribed ideas of lack of restraint and chaotic behavior unto the represented scenes, but also made a value judgment on the practices as unbound, uncouth, and lacking civility.[22]

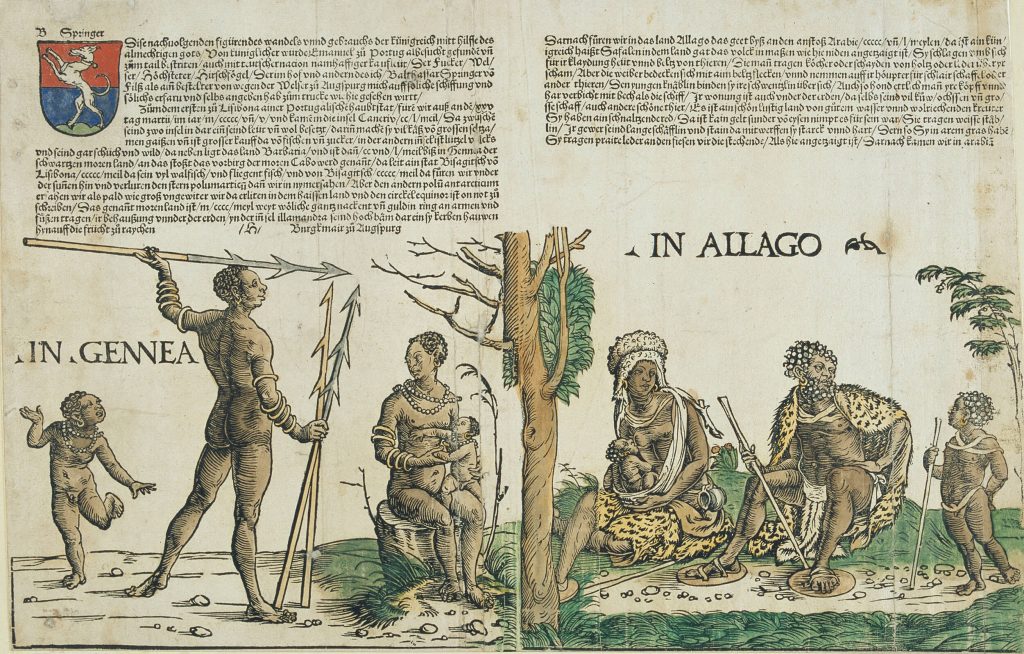

Compare the Dance of Death skeletons to German artist Hans Burgkmair’s (1473–1531) depiction of an African child in his proto-ethnographic 1508 woodblock print of the people of “Gennea” (Figure 5.4). The child clumsily balances on one foot in his flailing imitation the impressive warring gesture of his father whose mastery is rendered, in contrast, in a dynamic[168] but stable contrapposto. The baby in the arms of the poised mother figure also twists as to wiggle out of the woman’s grasp. The attitude of the standing child would evoke to its early modern viewers images of both moresca dances and the dance of death.[23] The clumsy gesture and unselfconscious nakedness of the child also conjured ideas of naive innocence that European travelers to Africa and the Americas repeatedly associated in their reports with Indigenous people, who “go around” “naked” “with no shame at all.”[24] The juxtaposition of the African man pictured in a classical contrapposto and the African child in an[169] exuberant stance, of the wiggling baby and the African woman seated as a Christian Virgin Mary, also reveals ambivalences and contradictions about the nature, limits, and stability of difference that would remain central to European conception and representations of racialized Others.

Hans Burgkmair, “Natives of Guinea and Algoa,” 1508, handcolored woodcut (28.5 × 42.4 cm). Freiherrlich von Welsersche Familienstiftung, Neunhof (Photo credit: copyright Freiherrlich v. Welsersche Familienstiftung)

Art historian Stephanie Leitch has rightly underlined how the figures testified to Burgkmair’s “virtuoso exploration of movement for its own sake” that not only pushed the boundaries of the medium of wood printing, but also explored new possibilities for ethnographic visual representation.[25] Burgkmair’s print is part of a multiblock series based on Balthasar Springer’s travelogue The Voyage and Discoveries of New Paths to Many Unknown Islands and Kingdoms chronicling his 1505–1506 journey along the coast of Africa to India’s Malabar Coast. Though not directly the product of eye witnessing on the part of the printmaker, the series is at least partly inspired from sketches executed in situ by a travel companion of Springer’s.[26]

An innovative combination of modes of showing otherness in the medium, from physical features to cultural traits, supports the print’s ambition to achieve visual empiricism. Inked lines bring volume to the curves of the figures and successfully evoke dark skin. Curly hair and rounded noses pinpoint the physical features Europeans most often associated with Africans. Necklaces and bracelets suggest socially meaningful adornment that highlight the absence of clothing, the first and most preeminent means of outward[170] social identification in Europe, the latter a point Kaplan and Katz discuss in this volume. This same idea of imperfect civility that emerges from showing lack of clothing paired with the presence of adornment is taken up in the motif of the half tree trunk on which the woman sits. The trunk highlights the lack of furniture, as the tree to the right highlights the lack of dwelling, but it nonetheless visibly suggests human industry. Its flat top is manufactured, the result of human intervention. Finally, the unbalanced attitudes of the children destabilize the poise of their parents, making their genteel poses seem happenstance rather than stable characteristics of comportment “in Gennea.” In presenting this array of visual solutions to the depiction of the other, Burgkmair’s print demonstrates the possibility of showing race in the medium but does not give an authoritative statement on the necessary or even the sufficient visual means for this representation. Rather, in addition to physical features, Burgkmair relied on what his European viewers would perceive as unbalanced bodily comportment and imperfect social values to denote racial difference. Already in this early moment, reckonings with the possibility of visual racial representations turns to movement, in conjunction with physical features and clothing, as a powerful marker of difference.

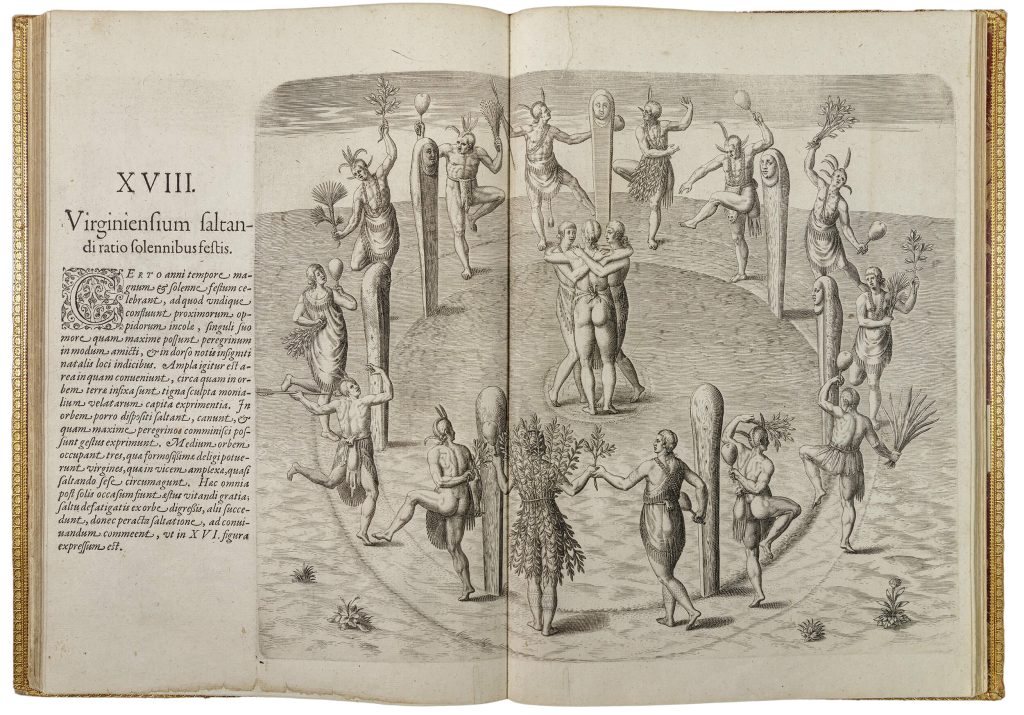

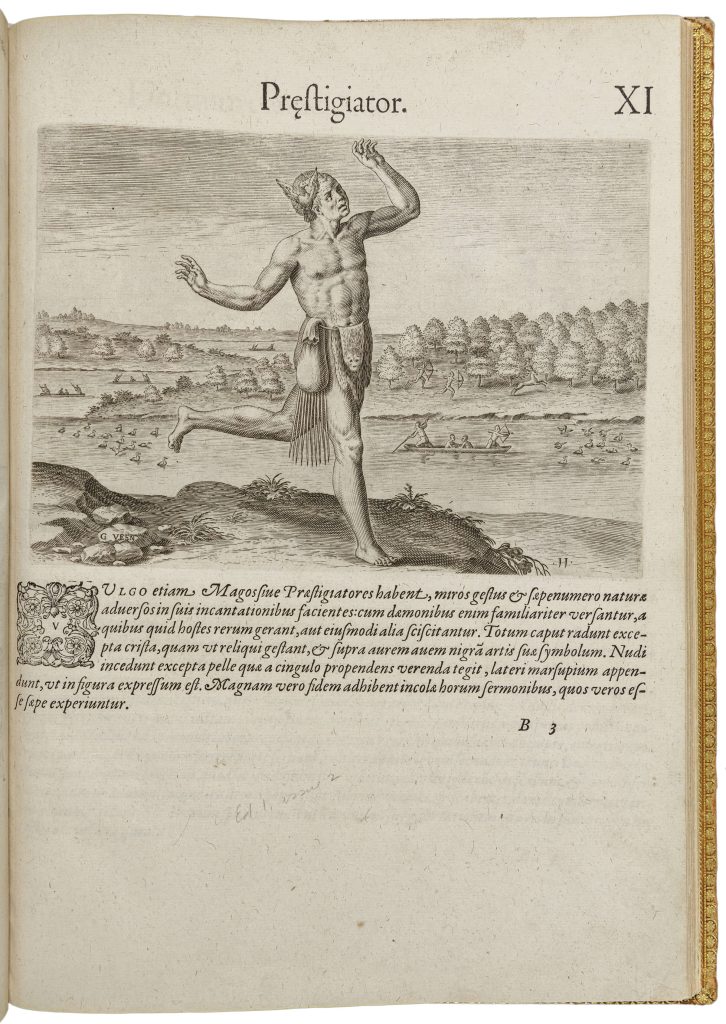

Leaps and flying, bent limbs demonstrating excess and imbalance appeared in the dance of death alongside another feature iconographically associated with paganism: the ronde.[27] It is a ronde of naked men in dynamic motion suggesting dance that forms, for instance, what is likely the first European painting of Indigenous Americans, executed in 1494 by Pinturicchio (Bernardino di Betto, 1454–1513) in Pope[171] Alexander VI Borgia’s (1431–1503) apartments.[28] At the end of the sixteenth century, the attitude of the high stepping skeletons in the ronde seen in Wolgemut’s dance macabre appears in cartographers John White’s (1539–1593) watercolor representations of the Indigenous people of Roanoke Island in the emerging English colony of Virginia. The scenes painted from life in 1585 would circulate widely in their engraved versions in an edition of Thomas Harriot’s (1560–1621) travelogue edited by Theodor de Bry (Figure 5.5). Stepping high and waving their arms, a group of Indigenous men and women dance around a set of posts and a central group in a ritual scene. In fact, the ronde and dynamic limb movement regularly appeared in European illustrations of otherness, real or imagined, from paganism to witchcraft, and from the Americas to Africa.[29] In another image from the same publication, the twisted body and flailing limbs of a “conjurer” caught mid-trance conveys his overtake by numinous forces (Figure 5.6).

Theodor de Bry, “Virginiensium saltandi ratio solennibus festis,” in America. Pt. 1, Frankfurt am Main, 1590, Newberry Library, VAULT Ayer 110 .B9 1590b v. 1

Theodor de Bry, “Prestigiator,” in America. Pt. 1, Frankfurt am Main, 1590, Newberry Library, VAULT Ayer 110 .B9 1590b v.1

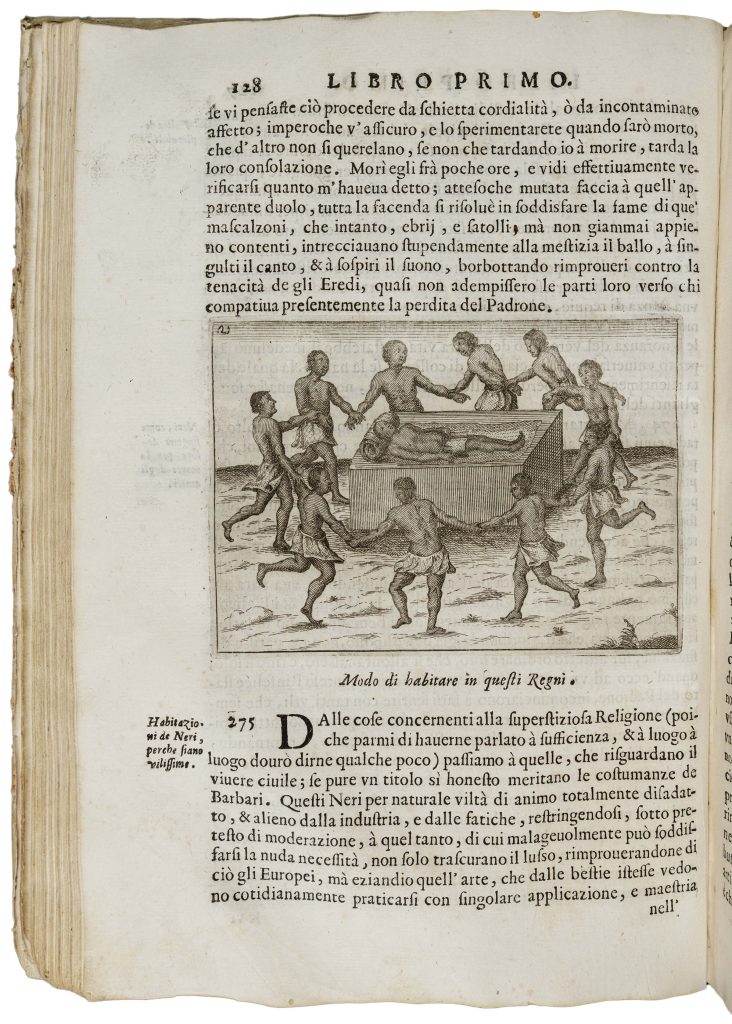

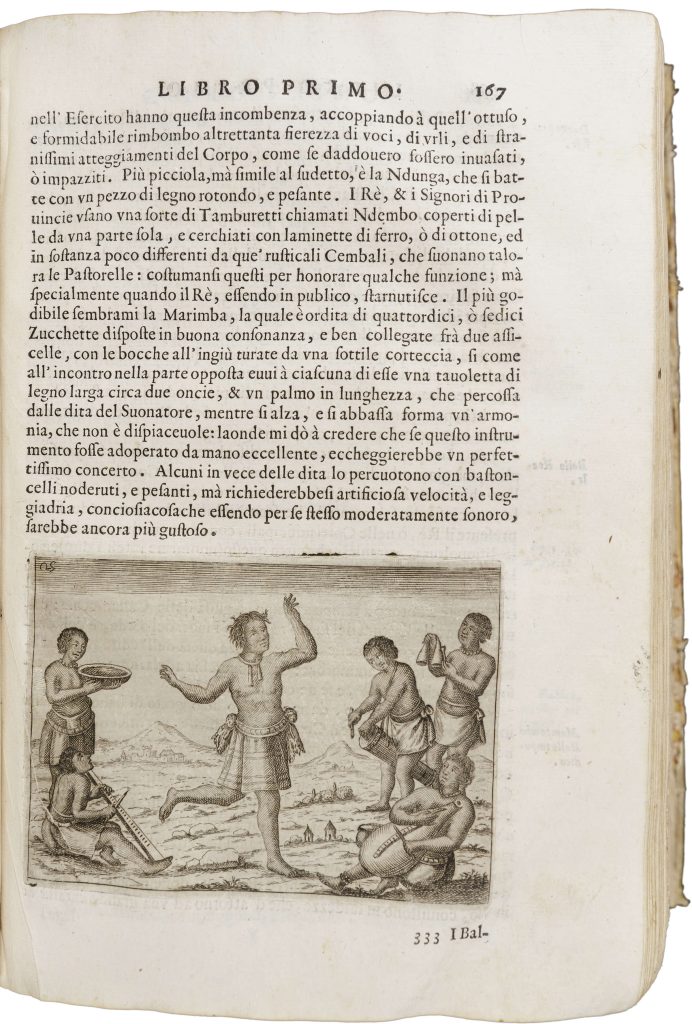

A century after Harriot, a Capuchin missionary in the Kongo turned to the same set of gestures to convey ritual dancing in central Africa in watercolors later published as etchings in Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi’s Historical Description of Three Kingdoms published in 1687 (Figures 5.7 & 5.8).[30] In what the cleric perceived as an idolatrous funeral ronde, or in “dishonest balls” the same movements continued to mark[172] non-European individuals as culturally strange, morally suspicious, and spiritually compromised. Movement, thus, along with dress and skin color, served as a marker that early modern Europeans read as a sign of lack of civility, religion, and social sophistication.[31] It would unsurprisingly feature in the visual vocabulary of idolatry in the early eighteenth-century publication by Bernard Picart, the Ceremonies and Religious Customs of the World, whose impact on European perceptions and representations of religions worldwide would be felt for centuries (Cat. No. 38).[32]

Paolo da Lorena (attr.), Plate 23 in Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi and Fortunato Alamandini, Istorica descrizione de’ tre’ regni Congo, Matamba, et Angola, Bologna, 1687, Newberry Library, Ayer 263 .C211 C2 1687

Paolo da Lorena (attr.), Plate 25 in Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi and Fortunato Alamandini, Istorica descrizione de’ tre’ regni Congo, Matamba, et Angola, Bologna, 1687, Newberry Library, Ayer 263 .C211 C2 1687

Pious Stances

Contrasting with the “savage” comportment evinced in depictions of Africans and Indigenous people ranging from dancers to ritual specialists or vanquished enemies, visual representations of the Other linked to Christian piety displayed them in attitudes with positive connotations. One of the common markers, for example, of Blackness in Spanish Viceregal visual and literary rhetoric was a servile or supplicant position, often rendered in conjunction with a childlike appearance.[33] This trope, already well established in the seventeenth century, can also be seen in the following century, for instance in a 1750 painting of Saint Luis Beltrán Baptizing an African Slave (Figure 5.9). Since the mid-sixteen hundreds, Saint Luis Beltrán (1526–1581) had been a patron of New Granada, which encompassed present-day Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, and Panama.[34] The Spanish Dominican spent most of his life in Valencia, Spain, but is best remembered for his missionary work in Colombia, Panama, and the Lesser Antilles (1562–68).[35] In 1561 he sailed on a galleon to Cartagena, an important port city that received slave ships. He likely baptized newly arrived Africans in the port of Cartagena before embarking on his missionary work of converting Indigenous groups in the interior of the continent.[36] The painted scene takes place in a tropical setting communicated to the viewer via the palm tree in the right background emblazoned with a cross, alluding to the saint’s successful apostolate in the region. It features numerous symbols that refer to the saint’s life, including a small crucifix that emerges from the barrel of a rifle, evoking a miracle he performed in Colombia. Under attack by Indigenous Colombian warriors, the Dominican genuflected towards the weapon, which miraculously transformed into a crucifix.

Unidentified Artist, Saint Luis Beltrán Baptizing an African Slave, 39½ x 301/8 in, oil on canvas, Ecuador, 1750, Thoma Foundation

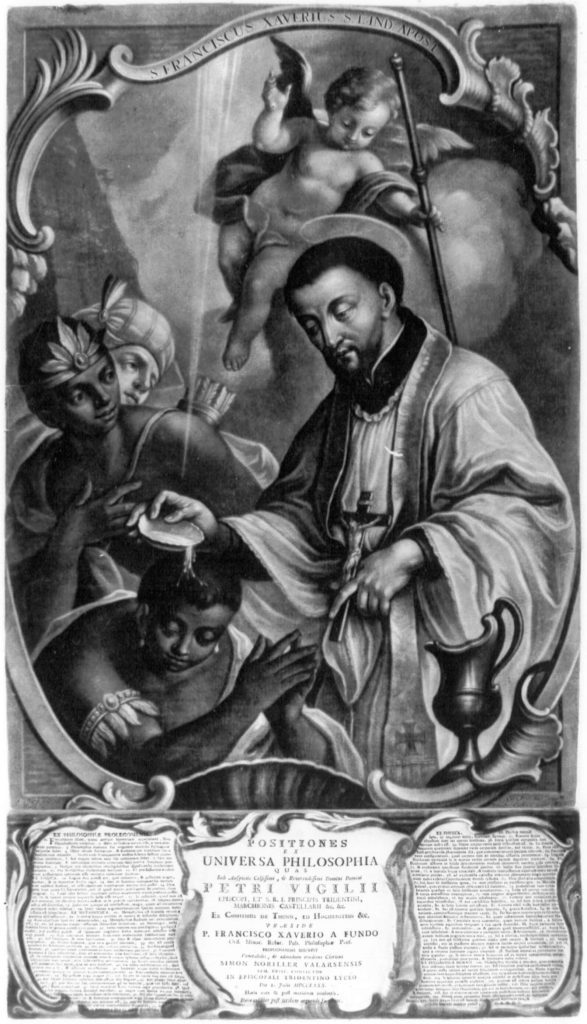

The small African figure wearing a billowing blue robe, a red feathered diadem, a drop pearl earring, and a jeweled, golden armlet is of particular interest. Such finery was a convention used to signal Africans as valuable commodities of those who owned them as slaves, and contrasts sharply with the image of the nearly naked Africans of the sugar mill or the ritual dances. The figure’s accoutrement is a fanciful riff based on various sources. It draws from the roughly contemporaneous engraving St. Francis Xavier Baptizing a Native produced by the Klauber workshop (Augsburg, Germany).[37] The Quito painter replaced the Old World Jesuit Saint Francis Xavier (1506–1552) with the New World Dominican Saint Luis Beltrán by changing the habit and substituting the emblems that identify each saint.[174]

In the print, Saint Francis Xavier wears the black colored and high collared Jesuit clerical robes (Figure 5.10). He holds a crucifix in one hand though he lacks his other symbols including the lily, ship, and flaming heart. That the Quito artist chose Francis Xavier’s image as a prototype makes sense considering the great fame of the Jesuit, known as the “Apostle of the Indies,” and that both saints were missionaries originally from Spain serving in foreign lands. In his new interpretation, the Quiteño artist collapsed the source engraving’s three figures adoring the saint to just one. In the Klauber workshop print, the three figures surrounding the saint allude to his mission in Asia. The two closest to the foreground, including the figure being baptized, have dark skin and wear feathered accessories including an armlet, headpiece, and quilled arrows. Behind them a lighter-skinned turbaned man looks outwards, a typical type that referred in the early modern period to a diffuse European idea of western Asia. The other two figures result from the collapsing of distant lands into the abstract idea of the Indies, a notion rather than a place denoting in early modern European thought an exotic, faraway, Other, elsewhere. In a similar process, the darker skinned figures who likely personify converts in Goa, India, where Francis Xavier spent much of his mission, are[175] depicted in the befeathered guise of the “savage” and are racialized as Black based on their dark skin color.[38] The Quito painter loses the arrow motif and collapses the feathered armlet and headdress into a singular dark-skinned figure. Here the various exotic types merge into the bozal (i.e. recently arrived to the Americas) African baptized by Saint Luis Beltrán.

Klauber Workshop. St. Francis Xavier Baptizing a Native, engraving, 18th century, Trento, Museo Diocesano Tridentino

The tendency to flatten exotic types was common in early modern Europe, and the collapsing of African types with both western Asian and Indigenous tropes frequent. For instance, feathers, while particularly emblematic of Indigenous Americans, also signified savageness in portrayals of individuals far outside of that geography.[39] Reversely, the feathered headdress (or penacho) of Motecozuma II was famously labeled a “Moor’s Hat” when first recorded in the 1596 inventory of Austrian Archduke Ferdinand II von Tyrol.[40] Similarly, early missionaries in New Spain erroneously called Mexica temples mosques.[41] In the seventeenth-century Wunderkammern, or cabinet of wonders, items from Africa and the Americas were often labeled “Moorish” or “Indian.” These interchangeable terms not only blurred Black and Indigenous American cultures into a singular foreign category, but also drew illogical equivalencies between simplified and inaccurate geographic, ethnic, religious, and racial signifiers.[42]

Returning to the diminutive African of the Quito School painting, the figure’s fanciful fineries are clearly exoticizing tropes, but could also suggest elite status, perhaps as an African noble just arrived in Cartagena.[43] That an African prince could arrive in the slave port in all his finery of course was pure fantasy, as the middle passage inflicted its physical and material wounds to all captives, no matter their former social status. Yet, in his allegorical role, the man communicated through[176] his small stature and supplicant posture the success of Beltrán in pacifying him and bringing him into the Christian faith. The African crosses his arms over his chest, a gesture that differentiates him from the “natives” of the source engraving, one of whom instead clasps his hands before himself in prayer. A subtle change perhaps, but the adjustment in gesture begs investigating. As art historian and co-editor of this volume Lia Markey describes, “The word ‘gesture’ derives from the Latin words gestura, meaning ‘bearing,’ ‘way of carrying’ or ‘mode of action,’ and gerere, the infinitive form, which means ‘to carry, to behave, to take on oneself, to take charge of, to perform or to accomplish.’”[44] Various treatises were written about gesture in the early modern period including John Bulwer’s 1644 Chirologia, or the Natural Language of the Hand (Cat. No. 13), based on the study of gesture in the ancient world, drawing from Cicero’s De oratore of 55 BCE.[45] If gestures serve as a visual language, one that art historian André Chastel describes as “para-language . . . a rhetoric of non-verbal communication,” what, then, does the crossed arm gesture communicate? [46] And how does that gesture differ from the hands in prayer from the engraving?

In the history of European art this attitude is perhaps best known in the pose of the Virgin Annunciate of Jan and Hubert Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece (c. 1425–1432).[47] Similar to our African figure, the future mother of Christ crosses arms in front of her chest while gazing upwards. The crossed-arm pose was popular in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Annunciation scenes, where they suggested the “Humiliatio” or submission of the Virgin Mary to divine will.[48] The crossed-arm gesture also has connections to church liturgy. The writings of ninth-century Amalarius of Metz describing the symbolism behind actions performed during mass associated crossed arms with the Passion, and particularly of Christ’s submission on the cross.[49] Following the consecration of the host, the crossed arms pose accompanied by a bow became part of Catholic liturgy by the early thirteenth century. Symbolizing Christ’s acquiescence to his sacrifice, the gesture held further associations through its use in various Biblical subjects.

The attitude shows up in scenes of the Baptism of Christ, such as in the Limbourg Brothers’ illumination for The Beautiful Hours of Jan, Duke of Berry (1410–15).[50] There, it foreshadows the Passion, the sacrifice that would redeem the sins that baptism could not wash away.[51] The pose appeared in various saints’ images, particularly those of penitential saints. Eventually it would show up in mythological or historical subjects where, as Wilberding describes, “it shear[s] away any theological references, only the idea of submission and reverence is retained.”[52] Submission and reverence is what the crossed-arm pose of the bozal baptizand signifies, emphasizing his conversion and piety.

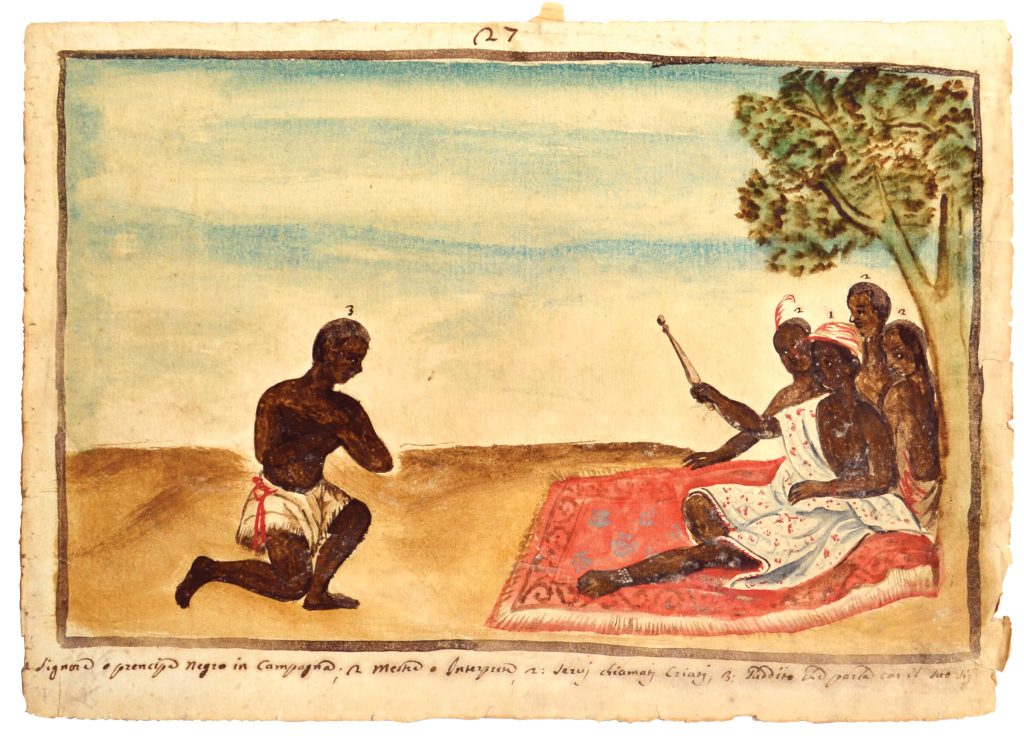

The pose also has Black Atlantic resonance. Art historian Robert Farris Thompson connects the gesture to the Cuban rumba yambu where it signifies communication or a greeting between parties.[53] The gesture’s Black Atlantic dimension arches to the early modern[177] kingdom of Kongo where it was a local attitude of greeting and respect. In a late seventeenth-century watercolor a vassal approaches his overlord, kneeling and crossing his arm in front of his chest in sign of deference (Figure 5.11). The image, part of an album aimed at instructing missionaries about their work in the Christian kingdom of Kongo, describes with ethnographic detail the mores and customs of the region.[54] It also functions analogically by likening the Kongo ruler in the act of adjudicating to the famed Saint Louis of France (1214–1270) who officiated similarly under a tree. The use of imported textiles and outfitting such as the crimson carpet reflects the cosmopolitan horizons of the aristocrats of the kingdoms, active in the commercial, diplomatic, and religious networks of the early modern Atlantic world. The figure of the Kongo noble and the gesture of the man before him also bring further perspective on the depiction of the African slave in the painting of San Luis Beltrán. The gestures and finery that the hagiographic painting[178] strives to naturalize as emblems and attitudes denoting enslavement appear in contrast in the watercolor as symbols and demonstrations of African civility and cosmopolitan sophistication. The comparison underlines the mechanics at play in the creation and interpretation of images such as the Quiteño canvas whose heavy-handed rhetoric contributes to the construction of race. Once relocated within a vaster set of early modern Atlantic visual, material, and gestural vocabularies, the attitude and adornment of the baptizand, which viewers are invited to see as the attribute of the “savage” for whom enslavement brings salvation, rightly become contingent on their ideological context. That early modern Europeans used gesture and movement in addition to skin color and physical features in crafting an early modern discourse of race helps underline the willful and strenuous mechanics that the arduous work of racialization demanded to be put into motion. It also brings attention to the enduring racialized meaning rooted in the early modern period of certain movements and bodily attitudes that are often today willingly or unwillingly overlooked as expressions of racialized discourse and often serve as terrains of resistance to it.

Unknown Capuchin artist, Black Lord or Prince in the Countryside, watercolor on paper, 34 ×24 cm, late seventeenth century, Parma Watercolors, folio 27, Virgili Collection, Photograph: C. Fromont

Conclusion

The preceding visual examples highlight some of the ways bodily comportment functioned as a racial marker in the early modern Atlantic world. Specific gestures, postures, and movement of Indigenous Americans as well as Africans and their descendants depicted in these images both further established and reified the European view of racialized people as naturally unruly and in need of pacification. Such views permeated colonial society. Throughout the Spanish Viceroyalties,* for example, legal codes separated Spanish, Indigenous, and Africans and conferred different laws based on these categories (see for example the patent of nobility and cedula in Cat. No. 40 & 23). These rules were made by and for Europeans who placed themselves within the system in a position of superiority, thereby legally enacting white supremacy.

Throughout the independence period, and indeed until the multicultural turn of the 1980s, many Latin American countries embraced what has been called a “monocultural mestizaje,” where ethno-racial diversity was ignored in favor of an ideological whitening of the population.[55] Often mestizos (mixed Spanish and Indigenous) were celebrated as the prototype of national identity.[56] Through the process of modern nation building in much of Latin America, Indigenous cultures were framed as part of the national past, thereby incorporating aspects of Indigeneity into a modern, whitened (and thus “improved”) mestizo nation. Blackness thereby continued to be relegated to the margins, prescribed as existing outside of the national imaginary. Only in approximately the last twenty-five years have many Latin American countries officially recognized their multiculturalism. This occurred in Ecuador, for example, for the first time in 1998, when the rewritten constitution acknowledged both Indigenous peoples and Afro-descendants as “indivisible” parts of the modern Ecuadorian state.[57] Yet still, Afro-Ecuadorians, like many other Afro-descendants in former colonies, continue to face discrimination and poverty.[58]

When we look at early modern images of difference, we can see many of the rooted attitudes of the colonial period that continued into the independence and post-independence periods. The visual record is[179] rife with images that projected the stereotype of an unruly, transgressive Black body that could be controlled only through European intervention. As demonstrated, the trope of the bowing, kneeling, submissive Black figure has a long history, seen in this paper’s examples as early as Weiditz and de Bry in the sixteenth century. What is more, this iconography that was once associated with otherness of many kinds would become increasingly associated with Blackness in particular. The kneeling African, for instance, came to be a trope for the “Black slave” type, and featured often in emancipation visual culture, perhaps most famously on the masthead of William Lloyd Garrison’s (1805–1879) abolitionist newspaper The Liberator.[59]

An 1846 medal commemorates the erection in Bogotá, Colombia of a statue of Simón Bolívar, known as “El Libertador.” One side of the medal reproduces a relief at the base of the statue (Figure 5.12). It shows Bolívar (1783–1830) standing at attention in classical contrapposto. He holds a book above a kneeling man behind whom crouches a nursing mother and child. Created by Italian Neoclassical sculptor Pietro Tenerani (1789–1869), the medal and relief celebrate Bolívar as the emancipator of South America’s enslaved African population. During his campaigns against Spanish occupation, Bolívar, a criollo, received aid from Alexandre Pétion (1770–1818), a man of color and the first president of the Republic of Haiti. In return, Bolívar vowed to free slaves in the areas he liberated from Spain. In the relief we see how the artist portrays Bolívar in contrapposto and with a three-quarter view of his face. In contrast, the African figures are shown in profile, a convention used to convey servitude. They are rendered with full lips and round noses, following European conventions for African phenotypes. The female figure has her hair covered, while the male figure’s hair is cropped short. In contrast with Bolívar’s tailored military costume, the Africans are in a state of undress, both wearing only draped cloth threatening to come loose on their bottom halves. Here their bodies, though rendered no different in color to that of Bolívar due to the nature of the medium, are nonetheless revealed as Black bodies. They look up to their emancipator in deference and gratitude, almost a secularized version of the saved African alongside Saint Luis Beltrán.

Tenerani and Voigt, Bolivar Freeing the Slaves Statue Inauguration, silver medal, 48.58 mm.; 57.96 gms, 1846, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, accession #2002–28

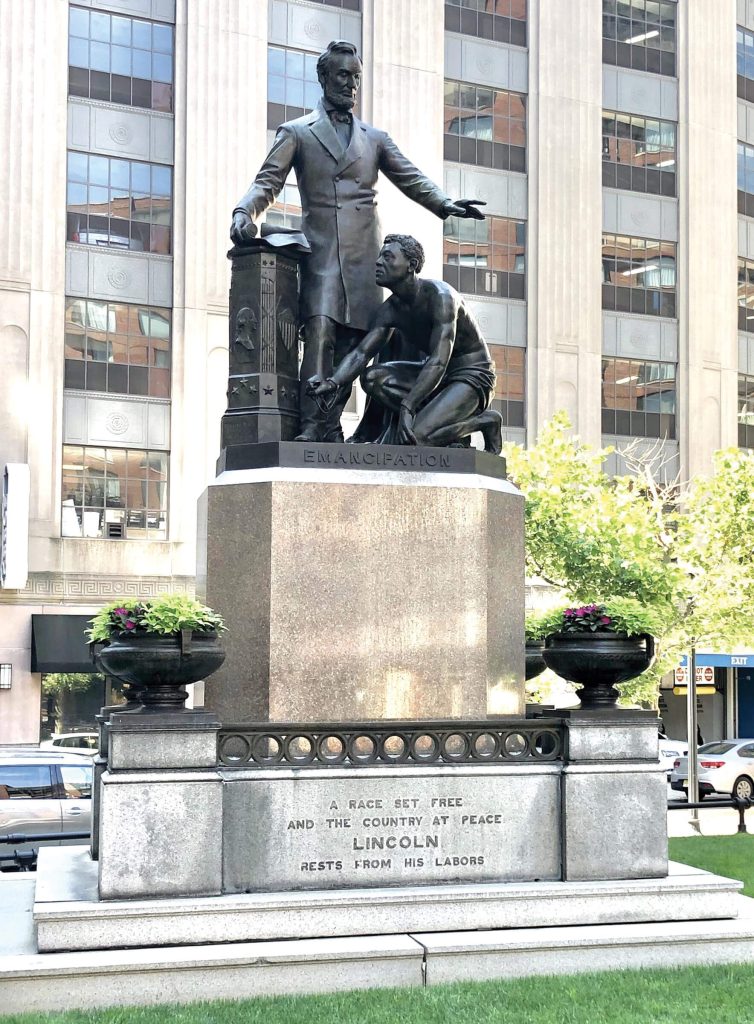

Such images and the racial hierarchies they herald have come under scrutiny in recent years. In December of 2020 the Boston Art Commission voted to remove a statue of Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865)[180] that includes a Black man at his feet, kneeling with broken chains around his arms (Figure 5.13).[60] The statue, a copy after a Thomas Ball (1819–1911) prototype in Washington, D.C., depicts Lincoln holding the Emancipation Proclamation. It was commissioned by Black freedmen and Union veterans. Of the original statue Frederick Douglas (1818–1895) wrote: “The negro here, though rising, is still on his knees and nude. What I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man.”[61] Douglas highlights the importance of embodiment in communicating status. Though perhaps rising as Douglas mentions, the figure is subordinate to Lincoln who is couched as the white savior, thereby denying the agency of enslaved people in their own liberation. In more recent years, of course, Black male athletes beginning with Colin Kaepernick (b.1987) have re-signified the kneeling stance from servile to one of empowerment and protest.

Copy of Thomas Ball, Emancipation Memorial, bronze, 1876, Boston

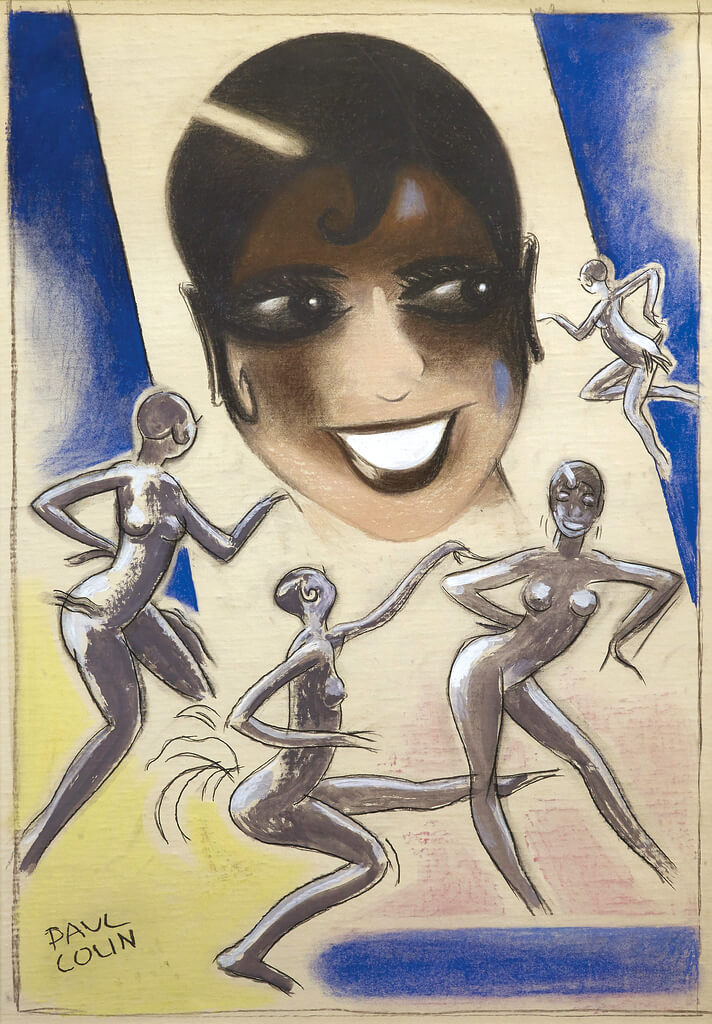

Along with pious stances, “savage” dances have a long posterity. The perceptions of Indigenous Americans, and to an even greater extent Africans and Afro-descendants as unrestrained and lacking civility that emerged and stabilized in the early modern period, continued to cast their long shadow in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In 1927, French illustrator Paul Colin (1892–1985) published Le tumulte noir, a portfolio of hand colored lithographs celebrating the African-American performers who shook the Parisian live stage of the Années folles, first among whom featured Josephine Baker (1906–1975).[62] The French visual artist’s depictions of the dancers and his written memoirs of his first experience of the Revue nègre demonstrate the enduring hold of the visual and textual vocabulary for the representation of non-European dance and movement honed in the early modern period. In “Harlem on the Champs-Elysees,” he wrote:

Harlem with its contortions, its howls, its multicolored feathers against coal Black skin, its banner of trembling or hardened buttocks, its pairs of provocative, yielding, athletic, jolly breasts! Harlem, with its starched shirt fronts, its cotton fabrics, its boaters, its gray bowler hats, its pomaded hairdos, and its odors, exported to Europe for the first time the Charleston.[63]

Undress or improper use of clothing, dynamic motions of the limbs and bodily stances, feathers and dark skin are as much a concern for the twentieth-century artist as they were for his early modern predecessors. In a 1930 drawing, Colin surrounds the smiling face of Josephine Baker, radiant in her lacquered hairdo and accroche-coeur curls, with four dancing silhouettes capturing her crowd-slaying Charleston (Figure 5.14). The high forward and backward kicks, flying elbows, and hip tilts enhanced by hints of feathers over her naked Black body that shocked and seduced the Parisian public in equal measure are the clear heirs of the early modern European imagery of the “savage dance.”

Paul Colin, Josephine Baker, crayon and gouache on paper, 1930, Framed: 44 in. × 321/2 in. × 11/2 in.), The Collection of Richard H. Driehaus, Chicago, inv. 49.2016.3

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the steps and attitudes Colin seized in his images had become under the brush, chisel, and etching needle of image-makers emblematic of European ideas of otherness. They still resonated as such in the primitivist project of Colin where they were no longer put to work to galvanize a contradistinctive European early modernity, but rather served as a provocative call to disband it. Colin saw in the movement of the dancer an otherness that he couched, along with the artistic avant-garde of the time, as a path towards “a new civilization, finally relieved of fetters centuries old.”[64] Yet, the celebratory discourse of primitivism was and still is in its twenty-first century iterations steeped in racist ideas of essentialized otherness.

In 2021, Josephine Baker became the first Black woman recognized by a cenotaph in the Panthéon, the French Mausoleum dedicated to its greatest national heroes. President Emanuel Macron (b. 1977) welcomed her in the monument as “War heroine. Fighter. Dancer. Singer,” praising her role in the Resistance against the Nazis during World War II, glossing as universalism her anti-racist activism, and not entirely avoiding the pitfalls of primitivist language in his rightful celebration of her embodied fight against racial prejudice.[65] Macron’s speech reframed Baker’s resistance and activism as emblematic of French[182] Republican values, where distinctions of race are subsumed under the homogenizing ideal of universalism. In doing so, it detached her struggle from the specificities of Black female experience of and resistance to racism. It also misread her powerful subversions of racialized discourse as a well-deserved, but ultimately gentle hand slap — or rather “hip swing” — brushing away the “clichés” held by an easily and willingly enlightened Parisian public.

The long historical perspective outlined in this essay reveals the deep currents underlying Josephine Baker’s provocative moves. Her performance was not an easily achieved correction of superficial prejudice, but intervened on the terrain of centuries-old processes through which Europe created ideas and images of racialized otherness in support of its imperial and colonial projects. Her dance and political moves had more to do with the sardonic, knowing, and ultimately grave jig of the allegory of death than those of the fantasized engraved savage. Grotesque humor was central to her performance. With crossed eyes and grimaces, she both enhanced and threatened to break the spell that her hypersexualized dance moves and nudity held over her public. With the same trenchant edge as her skeletal counterparts, she held her viewers in a powerful headlock, bringing them face-to-face with the image of their flawed social stances. As viewers questioned the civility against which they judged the performance as unacceptably and/or liberatingly “savage,” Baker’s humorous grimaces and knowingly grotesque moves spelled a counter-text. She drew from a long genealogy of Black women that mobilized power by subverting racialized ideas of their bodies as licentious, sexually available, and commodifiable. As generations of African and Afro-descendant women whose life was waged in slavery and post-emancipation-era on the terrain of the Black Atlantic, her body, in the words of historian Jessica Marie Johnson “enacted a radical opposition to bondage, reinterpreting wickedness as freedom, intimacy as fugitive, and Blackness as diasporic and archipelagic.”[66]

The images of back-breaking labor, “savage” dances, and pious stances, Baker continues to remind us, are not only European projections of ideas of Otherness with enduring power. They are also records of the deep challenges and efficacious resistance that African and Indigenous men and women inflicted on Europe’s ability to create and effect a worldview supporting their imperial desires and colonial ambitions.

- Grace Harpster, “The Color of Salvation: The Materiality of Blackness in Alonso de Sandoval’s De Instauranda Aethiopium Salute,” in Envisioning Others. Race, Color, and the Visual in Iberia and Latin America, ed. Pamela Anne Patton, 83–110 (Leiden: Brill, 2016); and Larissa Brewer-García, “Imagined Transformations: Color, Beauty, and Black Christian Conversion in Seventeenth-Century Spanish America,” Envisioning Others. Race, Color, and the Visual in Iberia and Latin America, ed. Pamela Anne Patton, 111–14 (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2016). ↵

- See Surekha Davies, “Climate, Culture or Kinship? Explaining Human Diversity c. 1500,” chap. 1 in Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 23–46. ↵

- Davies, Renaissance Ethnography, 40–41. ↵

- Thomas Harriot, Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia: of the Commodities and of the Nature and Manners of the Naturall Inhabitants . . .. trans. Richard Hakluyt (London, 1590). See Michael Gaudio, Engraving the Savage: The New World and Techniques of Civilization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 54–55. ↵

- Ananda Cohen Suarez [Aponte], “Making Race Visible in the Colonial Andes,” in Envisioning Others: Race, Color, and the Visual in Iberia and Latin America, ed. Pamela A. Patton, 187–212 (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 188. ↵

- Quintilian, Insitutio oratoria, trans. Harold Edgeworth Butler (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1922), 11.6.66, retrieved from Perseus Digital Library, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:2007.01.0069:book=11:chapter=6:section=66. See Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting and On Sculpture: The Latin Texts of De pictura and De statua, trans, Cecil Grayson (London: Phaidon, 1972), and Marjorie O’Rourke Boyle, “Deaf Signs, Renaissance Texts,” in Perspectives on Early Modern and Modern Intellectual History: Essays in Honor of Nancy S. Struever, eds. Joseph Marino and Melinda W. Schlitt, 164–92 (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2001). About dancing, see Jennifer Nevile, ed., Dance, Spectacle, and the Body Politick, 1250–1750 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008), 87. About gait and noble carriage of the body in early modern Italy, see Frances Gage, Painting as Medicine in Early Modern Rome: Giulio Mancini and the Efficacy of Art (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016), 76. For the link between movement of the body and movement of the soul since the early Middle Ages, see Stephen Kolsky, “Graceful Performances: The Social and Political Context of Music and Dance in the Cortegiano,” Italian Studies 53, no. 1 (1998): 14–16, https://doi.org/10.1179/its.1998.53.1.1. ↵

- As quoted in Sander L. Gilman, Stand Up Straight!: A History of Posture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 148. ↵

- Michiel van Groesen, “The De Bry Collection of Voyages (1590–1634): Early America Reconsidered,” Journal of Early Modern History 12, no. 1 (2008): 205, https://doi.org/10.1163/138537808X297135. Gage, Painting. ↵

- As quoted in Carmen Fracchia, ‘Black but Human’: Slavery and Visual Arts in Hapsburg Spain, 1480–1700 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 109. ↵

- K. Dian Kriz, Susan Danforth, and Elena Daniele, eds., Sugar and the Visual Imagination in the Atlantic World, circa 1600–1860. Providence: Brown University, published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, organized by and presented at the John Carter Brown Library, September 2013–December 2013, https://www.brown.edu/Facilities/John_Carter_Brown_Library/exhibitions/sugar/index.html. ↵

- B.W. Higman, “The Sugar Revolution,” The Economic History Review, New Series 53, no. 2 (2000): 213–36, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2598696; and Theodore De Bry, Nigritae exhaustis venis metallicis consciendo saccharo operam dare debent. In Americae pars quinta nobilis & admiratione plena Hieronymi Bezoni Mediolanensis secundae setionos Hispanorum . . ., 1595, image, John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, Providence, Accession no. 34724, https://mypages.unh.edu/hoslac/book/early-sugar-plantation. ↵

- Paul A. Scolieri, Dancing the New World: Aztecs, Spaniards, and the Choreography of Conquest (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013). ↵

- Michel de Certeau, Heterologies: Discourse on the other (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986). ↵

- Carolyn Dean, Inka Bodies and the Body of Christ: Corpus Christi in Colonial Cuzco, Peru (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999). Cécile Fromont, ed., Afro-Catholic Festivals in the Americas: Performance, Representation, and the Making of Black Atlantic Tradition, Africana Religions (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019). Lynn Matluck Brooks, The Dances of the Processions of Seville in Spain’s Golden Age (Kassel: Reichenberger, 1988). ↵

- Max Harris, Aztecs, Moors, and Christians: Festivals of Reconquest in Mexico and Spain (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000). ↵

- Cécile Fromont, “Dancing for the King of Congo from Early Modern Central Africa to Slavery-Era Brazil,” Colonial Latin American Review 22, no. 2 (2013): 184–208, https://doi.org/10.1080/10609164.2013.808466. Fromont, ed., Afro-Catholic Festivals. ↵

- John Forrest, The History of Morris Dancing, 1458–1750 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 74. Cf. Eugene McDowell Kenley, “Sixteenth-Century Matachines Dances: Morescas of Mock Combat and Comic Pantomime” (Ph.D. diss., Stanford, 1993), 1–2, 5–8, 11–12, 16–19, 30, 33–36, 53. Katherine Tucker McGinnis, “Moving in High Circles: Courts, Dance, and Dancing Masters in Italy in the Long Sixteenth Century” (PhD diss., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2001), 170–73. Michael Gaudio, Sound, Image, Silence: Art and the Aural Imagination in the Atlantic World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019), 8–10. Gaudio notes the use of the term morisque to describe Tupinamba dances in the 1585 edition of Jean de Léry’s report on Brazil. While the first edition of 1578 describes the dances as “rondes,” this later version, expanded by the author, specifically uses the term morisque as a comparison; see Jean de Léry, Histoire d’un voyage faict en la terre du Bresil, autrement dite Amerique: contenant la navigation, & choses remarquables, veuës sur mer par l’auteur: le comportement de Villegagnon en ce pays-la: les murs & façons de viure estranges des sauuages bresiliens: auec vn colloque de leur langage . . ., 3rd ed. ([Geneva]: Pour Antoine Chuppin, 1585), 137. ↵

- Esther J. Terry, “Choreographies of Trans-Atlantic Primitivity: Sub-Saharan Isolation in Black Dance Historiography,” Early Modern Black Diaspora Studies (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 65–82, 74–76, notes the mention of morescha at Kongo court in Lopes Pigafetta. See Duarte Lopes and Filippo Pigafetta, Relatione del reame di Congo et delle circonvicini contrade (Rome: Bartolomeo Grassi, 1591), 69. ↵

- Jennifer Nevile, The Eloquent Body: Dance and Humanist Culture in Fifteenth-Century Italy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004), 79. ↵

- Elina Gertsman, The Dance of Death in the Middle Ages: Image, Text, Performance (Turnhout: Brepols, 2010), 65–67. ↵

- William C. Sturtevant, “La tupinambisation des Indiens d’Amérique du Nord,” in Les Figures de l’Indien, Les cahiers du department d’études littéraires 9, ed. Gilles Thérien, 293–303 (Montréal: Typo, 1988). Elizabeth Hill Boone, “Seeking Indianness: Christoph Weiditz, the Aztecs, and Feathered Amerindians,” Colonial Latin American Review 26, no. 1 (2017): 39–61, https://doi.org/10.1080/10609164.2017.1287323. ↵

- Co-editor Noémie Ndiaye discussed a similar use of movement in early modern racecraft in England in Noémie Ndiaye, “‘Come Aloft, Jack-little-ape!’: Race and Dance in The Spanish Gypsie,” English Literary Renaissance 51, no. 1 (2021): 121–51, https://doi.org/10.1086/711604. ↵

- Interest in Italian dance, including the morescha, from Nuremberg in the early sixteenth century has been discussed in Ingrid Brainard, “The Art of Courtly Dance in Transition,” in Crossroads of Medieval Civilization: The City of Regensburg and Its Intellectual Milieu: A Collection of Essays, eds. Edelgard E. DuBruck and Rudolf Holbach, 61–79 (Detroit: Marygrove College, 1984). See also Ingrid Wetzel, “‘Hie innen sindt geschriben die wellschen tenntz’: le otto danze italiane del manoscritto di Norim-berga,” in Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro e la danza nelle corti italiane del XV secolo, Proceedings of the 1987 Pesaro Conference, ed. Maurizio Padovan, 321–43 (Pisa: Pacini, 1990). ↵

- See the citations gathered in Jill Burke, “Nakedness and Other Peoples: Rethinking the Italian Renaissance Nude,” Art History 36, no. 4 (2013): 724–25, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.12029. ↵

- Stephanie Leitch, “Burgkmair’s Peoples of Africa and India (1508) and the Origins of Ethnography in Print,” The Art Bulletin 91, no. 2 (2009): 151, https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2009.10786162. ↵

- Stephanie Leitch, Mapping Ethnography in Early Modern Germany: New Worlds in Print Culture. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 64–66. ↵

- Gaudio, Sound, Image, Silence, 6–18. ↵

- See Andrés H. Rubiano, “The First Painted Image of America in Europe: A Detail from Pinturicchio’s Resurrection in the Sala dei Misteri,” H-ART. Revista de historia, teoría y crítica de arte, no. 8 (2021): 286–304; Jessica Horton, Art for an Undivided Earth (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 149–51; Gaudio, Sound, Image, Silence, 11–16. ↵

- Gaudio, Sound, Image, Silence, 11–16. ↵

- Cécile Fromont, Images on a Mission in Early Modern Kongo and Angola (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2022). ↵

- Burke, “Nakedness,” 714–39. ↵

- See for example Bernard Picart, Le grand sacrifice des Canadiens à Quitchi-Manitou ou le grand esprit de Jean Frédéric Bernard, Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde (1723). ↵

- Brewer-García, “Imagined Transformations: Color, Beauty, and Black Christian Conversion in Seventeenth-Century Spanish America,” in Envisioning Others: Race, Color, and the Visual in Iberia and Latin America, ed. Pamela A. Patton, 119 (Leiden: Brill, 2015). ↵

- The region was an Audiencia called the New Kingdom of Granada (1549–1716), until it became a Viceroyalty in 1717. ↵

- “St. Louis Bertrand,” Dominican Friars Foundation, https://dominicanfriars.org/st-louis-bertrand/. ↵

- Suzanne Stratton-Pruitt, unpublished manuscript (Thoma Foundation). ↵

- The Klauber print was used as a thesis sheet print, possibly based on an earlier composition by Johann Georg Bergmüller (1688–1762), which may have been the source of the Quito School painting. See PESSCA: Project on the Engraved Sources of Spanish Colonial Art, https://colonialart.org/archives/locations/united-states/state-of-illinois/city-of-chicago/thoma-collection/6006a-6006b ↵

- Kathryn Santner, personal communication (Thoma foundation). ↵

- W. C. Sturtevant, “La tupinambisation,” 293–303. ↵

- Esther Pasztory, Aztec Art (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998), 280; and Khadijah von Zinnenburg Carroll, The Contested Crown: Repatriation Politics Between Europe and Mexico (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022), 87. ↵

- Gauvin Bailey, Art of Colonial Latin America (New York: Phaidon Press, 2005). ↵

- See Elke Bujok, “Ethnographica in the Early Kunstkammern and their Perception,” Journal of the History of Collections 21, no. 1 (2009): 17–32, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhn031, and Jessica Keating and Lia Markey, “‘Indian’ objects in Medici and Austrian-Habsburg inventories,” Journal of the History of Collections 23, no. 2 (2011): 283–300, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhq030. ↵

- Suzanne Stratton Pruitt, unpublished manuscript (Thoma foundation). ↵

- Lia Markey, “Gesture,” University of Chicago :: Theories of Media :: Keyword Glossary, accessed February 28, 2022. https://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/gesture.htm. See also Adam Kendon, “The Study of Gesture: Some Observations on Its History,” Recherches Semiotique/Semiotic Inquiry 2, no.1 (1982): 44–62. ↵

- Markey, “Gesture,” and Kendon, “Study of Gesture.” ↵

- André Chastel, “Gesture in Painting: Problems in Semiology,” Renaissance and Reformation 1, no. 10 (1986): 9, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43444573. ↵

- Jan Van Eyck, the Virgin Annunciate from the closed view. Back panels of Ghent Altarpiece. San Bavo. See https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ghent_Altarpiece_F_-_Maria_message_2.jpg. ↵

- Baxandall identifies a sermon by Franciscan Fra Roberto Caracciolo (c. 1425–95) on the five reactions of the Virgin Annunciate. Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 55. ↵

- Erick Wilberding, “Embracing the Cross: A Liturgical Gesture,” Notes in the History of Art 8, no. 2 (1989): 2. https://doi.org/10.1086/sou.8.2.23202528 ↵

- Paul Herman and Jean de Limbourg (Franco-Netherlandish, active in France by 1399–1416). Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry. 1405–1408/9. folio 211v. See “The Art of Illumination,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://blog.metmuseum.org/artofillumination/manuscript-pages/folio-211v/. ↵

- Wilberding, “Embracing the Cross,” 3. ↵

- Wilberding, “Embracing the Cross,” 4. ↵

- Robert Farris Thompson, Four Moments of the Sun: Kongo Art in Two Worlds (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1981), 168. ↵

- Fromont, Images on a Mission. ↵

- Jean Muteba Rahier, “From the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Contemporary Ethnoracial Law in Multicultural Ecuador: The ‘Changing Same’ of Anti-Black Racism as Revealed by Two Lawsuits Filed by Afrodescendants,” Current Anthropology 61, no. S22 (2020): 248–59, https://doi.org/10.1086/710061. ↵

- Most famously José Vasconselos (1889–1959), the Mexican reformist minister of education, wrote on the raza cosmica, or the cosmic race that inherited the “best” of their Spanish and Indigenous forbearers. ↵

- Rahier, “Transatlantic,” 251. ↵

- A 2019 United Nations report calls out the poverty in the region of Esmaraldas, a majority Afro-descendant province, as particularly indicative of such disparities. United Nations, “Much Work Needed to ‘Target Unacceptable Levels’ of Racism in Ecuador: Un Experts, UN News, accessed March 1, 2022, https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/12/1054201. ↵

- See the digitization of The Liberator via the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture: https://transcription.si.edu/project/11766. ↵

- Bill Chappell, “Statue of Lincoln with Formerly Enslaved Man at His Feet is Removed in Boston,” Race (blog), NPR, December 29, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/12/29/951206414/statue-of-lincoln-with-freed-slave-at-his-feet-is-removed-in-boston. ↵

- Jonathan W. White and Scott Sandage, “What Frederick Douglass Had to Say about Monuments,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 30, 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-frederick-douglass-had-say-about-monuments-180975225/. ↵

- Karen CC Dalton and Henry Louis Gates Jr., “Josephine Baker and Paul Colin: African American Dance Seen through Parisian Eyes,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 4 (1998): 903–34, https://doi.org/10.1086/448901. See selections from the portfolio at “Le tumulte noir: Paul Colin’s Jazz Age Portfolio,” National Portrait Gallery, https://npg.si.edu/exh/noir/ ↵

- [181]Paul Colin, La Croute (Souvenirs) (Paris, 1957), 74. Translation from Dalton and Gates Jr., “Josephine Baker,” 920. ↵

- Dalton and Gates Jr., 921. ↵

- “Discours du Président de la République à l’occasion de la cérémonie d’entrée de Joséphine Baker au Panthéon,” Élysée, 30 novembre, 2021, https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2021/11/30/josephine-baker-entre-au-pantheon. ↵

- Jessica Marie Johnson, Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 10. ↵

place where something happens, in the literal or figurative sense

ancient medical theory still in vogue during the early modern period, according to which a healthy body had a balanced combination of four liquid humors: blood, phlegm, bile, and melancholy. External factors, including geography and environment, were believed to influence that humoral balance

manners and moral attitudes towards those manners

act of bestowing catechism in order to convert people

eagerness to convert others to one’s own religion

technique that uses fine lines in proximity in order to create a shade effect in a drawing or an engraving

moving towards a strategically pre-determined endpoint

position in which one leg holds the full weight of the subject’s body

travel-focused narrative

in the very place in question

method for forming knowledge based on sensory experience

by means of iconography

painting whose paint is made with a water-soluble binder and thinned with water rather than oil

relative to theology, the knowledge and study of God and religion

person who receives baptism

relative to the account of saints’ lives

colonized territory ruled by a Viceroy in the name of a foreign king

section in a newspaper (often on the editorial page) giving information such as the owner’s name, a list of the editors, the advertising and subscription rates

commemorative monument dedicated to a person buried elsewhere

relative to an archipelago, a group of islands scattered over a body of water