When Students Recognize Gender but Not Race: Addressing the Othello-Caliban Conundrum

Maya Mathur

[print book page number: 15]

Carol Mejia-LaPerle ended her talk at the 2019 RaceB4Race symposium, “Race and Periodization,” with the following question: “As we commit to anti-racist efforts in our thinking, researching, and teaching, what materials, archives, histories and experiences can we put beside each other?”[1] She suggested that juxtaposing historical documents, contemporary texts, and experiential narratives might offer one avenue for exploring the continuities between past and present attitudes toward race. Katherine Gillen and Lisa Jennings make a similar claim when they call on teachers to decolonize Shakespeare by highlighting the racist contexts and colonial legacies of his plays; facilitating intersectional readings of his work; assigning responses to his plays by BIPOC artists and critics; and providing students with opportunities to engage creatively with his work.[2] The layered approach that Meija-LaPerle and Gillen and Jennings mention is vital at a time when well-funded white supremacist and anti-immigrant campaigns seek to ban discussions of race and racism in the classroom.[3] The antiracist approaches to teaching that they advocate are an important rejoinder to the attempts to silence discussions about race and racism in early modern literature. [16]

In the Predominantly White Institution (PWI) where I teach, this silence often stems from my students’ lack of experience, and resultant discomfort, with conversations about race. This reluctance is evident in their responses to Othello (1603–1604) and The Tempest (1611), plays that chronicle the oppression that their non-white characters, Othello, a Moor, and Caliban, an Indigenous figure, face at the hands of white Europeans.[4] On the surface, Othello and Caliban are quite different. Othello is a respected general in Venice while Caliban is a servant to Prospero and Miranda, the banished Duke of Milan and his daughter who occupy his island. Despite the external difference in their circumstances, Othello and Caliban share one trait: their persecution is predicated on their desire for white women. Othello’s position in Venice is threatened when he marries Desdemona, the daughter of Brabantio, a Venetian senator, and shattered completely after he murders her at the instigation of his ensign, Iago. On a related note, Caliban loses his freedom when he tries to rape Miranda in an attempt to wrest control of the island from Prospero.

The oppression of non-white men who display hostility towards white women represents a conundrum for many of my students: Should they sympathize with Othello and Caliban after their abuse of Desdemona and Miranda? Would they condone the violence against Desdemona and Miranda in doing so? How should the men in power, such as Brabantio, Iago, and Prospero, who enable gendered violence but do not perpetrate it, be treated? The students in my courses on Shakespeare have typically responded with sympathy to the mistreatment of Desdemona and Miranda but been more equivocal in their response to the racial hostility directed at Othello and Caliban. On the one hand, student sympathy towards Desdemona and Miranda, whose male guardians habitually silence them, is understandable. Indeed, for students coming of age in the #MeToo era, privileging Desdemona’s and Miranda’s plight over the hostility directed towards Othello and Caliban may appear to be the natural, even feminist, position to take when interpreting Othello and The Tempest. At the same time, their unwillingness to extend similar consideration [17] towards Othello and Caliban suggests a concomitant failure to recognize and acknowledge their suffering.[5]

In this essay, I explore the potential reasons for my students’ silence and discuss strategies to help create greater awareness of race and racism in Othello and The Tempest. As David Sterling Brown notes, however, teachers do their students a disservice if they focus on how race affects minority characters while ignoring its impact on white characters.[6] Just as important, Kim F. Hall maintains that “concentrating only on the ‘other’ may not be antiracist since it does not necessarily engage in issues of power.” [7] Taking these arguments as a starting point, I draw attention to the ways in which privilege informs and protects white characters even as it isolates and marginalizes non-white characters in Othello and The Tempest.

I assign these texts, and the historical materials that accompany them, with the awareness that my students’ overlapping identities will generate a wide variety of responses, from experiences of white fragility — feelings of discomfort or resistance to conversations about race — to distress at the long history of racial oppression that is reflected in the plays.[8] I seek [18] to address these responses to the play with a content note on my syllabus that I read during the first class session and reiterate whenever we read texts that involve language or imagery that students may find upsetting. The note states, “Your well-being is important to me, as is your success in the course. You should be aware that the texts we study are early representations of early modern race-thinking; that is, they traffic in religious and racial stereotypes that may be emotionally challenging to read. Some of the texts we read also contain references to sexual violence and ableist language and imagery. I will flag these texts before we read them and will be available to discuss your reactions to them.” I try not to assume that white students will be unaware of the racist discourse in the plays or that non-white students will wish to discuss racist elements of the text.[9] Instead, I seek to be mindful of the multiplicity of student reactions the play might generate while facilitating a discussion about the roles that privilege and oppression play in the materials under examination.

In the balance of this essay, I outline strategies that I use to raise awareness of the intersections of race and gender in Othello and The Tempest in a course on Shakespeare and race. The questions I asked myself when designing the course were as follows: What tools could I use to create greater awareness of how racial injustice intersects with gendered violence in Othello and The Tempest? What methods could I employ to illustrate the harm that is inflicted on non-white characters in these plays and generate greater awareness of the structural oppression they face? I address these questions through a layered methodology that includes historicizing representations of race, close reading raced and gendered language in the plays, exploring visual representations of the plays, and investigating the treatment of race and gender in modern adaptations. This approach to course design has helped generate more complex discussions of the stereotypes about race and gender presented in these plays and the extent to which Othello and Caliban can resist them. While I developed these strategies for a course on Shakespeare and race, the [19] units on historicizing, close reading, visualizing, and adapting the plays that I discuss below may be modified for discussions of Othello and The Tempest in high school and college classrooms.

Historicizing Race

There is a rich history of scholarship on Othello and Caliban as raced figures. While I recommend a selection of this scholarship to my students, I have found that teaching Ayanna Thompson’s essay, “Did the Concept of Race Exist for Shakespeare?” in concert with Ibram X. Kendi’s chapter, “Human Hierarchy,” can help illustrate how ideas about race were formed and circulated in the early modern period.[10] Kendi’s chapter provides the context for early modern race-making by explaining how classical theories of racial difference and early modern treatises that were used to justify the transatlantic slave trade.[11] Thompson’s essay introduces readers to the concept of race-making or racecraft, the process through which racial ideologies were constructed, and examines their circulation in Shakespeare’s plays. Taken together, these texts help students understand the ways in which early modern Europeans created racial categories to justify enslavement and colonization in Africa, Asia, and the Americas.[12] These essays provide the context for the historical documents that students engage with when studying Othello and The Tempest and provide them [20] with the tools to critically analyze these artifacts. Teaching the essays at the beginning of the semester helps students recognize when characters are echoing the racial ideologies of their time and when they are challenging its tenets.

I provide students with some of the cultural contexts for Othello by assigning the anonymous ballad, “The Lady and the Blackamoor” (c.1569–1570) and an excerpt from George Best’s Discourse of Discovery (1578), at the beginning of class discussion on the play.[13] The ballad features a villainous Moor who responds to being chastised by the lord he serves by kidnapping his master’s wife and children and gleefully plotting their deaths. The ballad rehearses a series of stereotypes about Moors as dishonest, rapacious, and bloodthirsty that I use to frame the close-reading of the text.[14] Students reading the ballad alongside Act 1, Scene 1 of the play can point to the similarities between the disgruntled Moor and Iago, and note the contrast between him and Othello. These contrasts can be used to suggest that Shakespeare was challenging established images of Moorish violence in his initial construction of Othello.

Interestingly, Othello does not simply reverse the positions of ensign and lord from “The Lady and the Blackamoor.”[15] The second document we study, George Best’s Discourse of Discovery, complicates Shakespeare’s portrayal of Othello and Iago in other ways. In the excerpt we read, George Best offers three reasons to account for the blackness of the people who inhabit the Torrida Zone, whom he refers to variously as either [21] Black Moors or Ethiopians — the hot climate in which they live, a natural infection that they pass on to their heirs, and a consequence of sin stemming from Cham’s disobedience of his father, Noah, which was punished in the black skin of his children, but ultimately settles on the curse of Cham as the most satisfactory explanation for this condition. Best writes, “And of this black and cursed Chus came all these black Moors which are in Africa, for … Africa remained for Cham [Ham] and his black son, Chus, and was called Chamesis, after the father’s name, being perhaps a cursed, dry, sandy and unfruitful ground, fit for such a generation to inhabit. Thus, you see that the cause of the Ethiopians’ blackness is the curse and natural infection of blood.”[16] I assign Best’s Discourse toward the end of class discussion on Othello in order to ask a series of open-ended questions on the extent to which Best’s theories of race, especially his notion of infection and sin, inform the play. These might include the following: Which characters infect, and which characters are infected? How does the notion of infection shift and change during the course of the play? Is the infection literal, figurative, or a combination of the two conditions? Students often focus on Othello’s increasing consciousness of his blackness as well as Desdemona’s growing association with her mother’s Black maid, Barbary, to view the play as confirming Best’s theory by locating blackness as a metaphorical infection that Othello passes on to Desdemona. Still others read against the grain of Best’s treatise by describing Iago as the source of an infection that damages the characters he comes into contact with his racist and misogynist beliefs. Using these materials can sensitize students to the ways in which Othello might destabilize Best’s race-making even as it appears to confirm his views.

I employ similar methods when teaching The Tempest in relation to early modern narratives about colonization. I begin by having students read excerpts from two documents, Richard Hakluyt’s Reasons for Colonization and Michel de Montaigne’s “Of the Cannibals,” from the Bedford/St. Martin’s edition of The Tempest (2000). I assign Hakluyt’s treatise early in our discussion of the play since the author uses it to advocate for England’s assertion of religious and military authority over the Americas. For [22] Hakluyt, this exercise of hard and soft power will supply England with a regular supply of cheap commodities and provide its manufacturers with a ready market in which to sell their goods. As he asserts when writing of Indigenous groups who may be reluctant to trade with the English, “they shall not dare to offer us any great annoy but such as we may easily revenge with sufficient chastisement to the unarmed people there.”[17]

After they read Hakluyt’s text, I ask students to outline his central claims regarding the land that is about to be colonized as well as its inhabitants. Then, we consider the extent to which Hakluyt’s formulation is applicable to Prospero, Trinculo, and Stefano’s plans for the island and its inhabitants in The Tempest. Students note that, unlike Hakluyt, who was invested in extracting material wealth from the Americas, the play’s colonizers are more interested in exploiting the workers that the island provides. Students point to the magic that Prospero harnesses from Ariel and his fellow spirits as well as the labor he extracts from Caliban as signs of his status as a colonizer. I also ask students to list the strategies that Prospero uses to maintain his power, especially with a rebel like Caliban in his midst. Finally, students compare Prospero’s successful exertion of his authority with Trinculo and Stefano’s comic attempts to play the colonizer with Caliban. As they note, Trinculo’s desire to profit by displaying Caliban’s body in England and Stefano’s desire to be king of the island are comic instantiations of Hakluyt’s playbook for conquest. Reviewing a text like Hakluyt’s Reasons generates awareness of the ease with which European characters asserted their authority over the natives they encountered and illustrates the dehumanizing nature of colonial contact. Situating Caliban within the discourse of colonization thus creates greater awareness of the cycle of labor and punishment that he endures on the island and helps frame his desire to escape it.

The relationship between Montaigne’s “Of the Cannibals” and The Tempest is more complicated. Montaigne’s essay champions what he sees as the egalitarian government of the Tupinamba people in Brazil — and by extension other Indigenous people in the Americas — whom he represents [23] as free from the corrupting influence of Europe’s political, legal, and economic institutions. As Montaigne notes, the inhabitants of the Americas are “a nation … that hath no kind of traffic, no knowledge of letters, no intelligence of numbers, no name of magistrate, nor of politic superiority; no use of service, of riches, or of poverty; no contracts, no successions, no partitions, no occupation but idle.”[18] Montaigne’s view finds an unlikely advocate in Gonzalo, the king of Naples’s counselor, whose folly in imagining a democratic kingdom in which he can anoint himself king is mocked by Antonio and Sebastian, the play’s villains. Gonzalo’s speech echoes Montaigne’s, especially in the suggestion that the island would involve “no kind of traffic / … no name of magistrate / Letters should not be known; riches, poverty / And use of service, none” (2.1.145–148). The affinities between Montaigne and Gonzalo’s words, like the alignments between Hakluyt and Prospero, Trinculo, and Stefano, can generate important discussions about Shakespeare’s engagement with discourses of colonization.

I accordingly ask students to read this exchange and consider the following questions in light of Montaigne’s essay: Should we take Gonzalo’s vision of a society in which all things are held in common seriously? Or, should we agree with Antonio and Sebastian that the system that Gonzalo imagines is unworkable in practice? If we agree with the play’s villains, are we also complicit in their view that the only system of government possible is one that is built on conquest? Most students respond to this question by suggesting that Shakespeare sets Gonzalo up to be mocked by the readers. They are less certain of how to read Antonio and Sebastian’s vision of authority, a vision that Caliban shares when he calls on Stefano to murder Prospero and seize the island from him. Caliban’s thirst for violence, like his assault on Miranda, aligns him with the usurping younger brothers, Antonio and Sebastian, and against the seemingly benevolent patriarchs, Prospero and Alonso. Placing Hakluyt and Montaigne in conversation with the characters who are disempowered in The Tempest can provide students with insight into why they rebel and how their political [24] beliefs have shaped their rebellion — beliefs that originate in Europe and not the island.[19]

Close Reading for Race/Gender

Historical documents help students theorize the oppressive regimes within which Othello and Caliban operate, but they do not do enough to disrupt the racial baggage — the unacknowledged or unconsidered assumptions about race — that students bring to the classroom.[20] This baggage is shaped by a media landscape in which racial, religious, and gender “outsiders” are treated with suspicion, whether this involves rhetoric that defends the police killing of unarmed Black men, upholds anti-immigrant sentiments, or supports legislation targeting transgender communities. Students raised to be uncritical recipients of social media may buy into negative stereotypes about marginalized communities just as often as they might question them.[21] The messages that students receive online might make them more susceptible to the pronouncements of characters like Prospero and Iago than those of outsiders like Othello and Caliban. Moreover, students may grow to question the oppressive ideologies of Iago and Prospero, but rarely question the moral authority of the plays’ heroines, Desdemona and Miranda. Indeed, once virtue is aligned with racial and gender superiority, it becomes constitutive of a dramatic ideal that Desdemona and Miranda embody and that Othello and Caliban cannot live up to. [25]

To start, I create greater awareness of unacknowledged structures of exclusion in the plays by introducing students to the concepts of privilege and intersectionality outlined by Peggy McIntosh and Kimberlé Crenshaw in their seminal work on race and gender.[22] In her essay, “White Privilege and Male Privilege,” McIntosh defines privilege as a series of unearned advantages that confers power on the dominant group. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s definition of intersectionality offers a necessary complication of McIntosh’s work by highlighting the overlapping axes of oppression to which non-white women are often subjected. I introduce students to the concepts developed by these authors in order to illustrate the privileges that white women and non-white men may have on account of their race and gender and to differentiate their position from those of two non-white women, Desdemona’s Black nursemaid, Barbary, and Caliban’s mother, Sycorax, who are marginalized because of their race and gender. I draw attention to these overlapping axes of privilege and oppression at the beginning of the semester so that students are better prepared to recognize them and chart their circulation in the characters and language of the plays.

I ask students to consider how these concepts operate in Othello and The Tempest through a series of close-reading activities that examine how white male power is upheld and whether white women like Desdemona, Emilia, and Miranda, who have race privilege but experience gender subordination, can exercise similar authority. In addition, these activities are designed to uncover how racial privilege is used to demonize Othello and Caliban. My goal for this exercise is to help students recognize the history and genealogy of racism that is situated in the language of the plays and that they may not recognize as racialized.[23] Often, these activities involve examining the racialized language that white characters use to vilify [26] Othello and Caliban. For instance, I have students interrogate the axes of privilege in Othello through its opening sequence where Iago, Roderigo, and Brabantio use a series of racial epithets to describe the relationship between Othello and Desdemona. I ask the class to catalogue the stereotypes of race that emerge in this exchange. These epithets include Iago and Roderigo’s dehumanizing references to Othello as “the thick lips,” “black ram,” “Barbary horse,” and “devil” (1.1.67, 91, 93, 113), and Brabantio’s accusation that Othello is a “foul thief,” a “thing,” and practitioner “of arts inhibited” who has trapped his daughter by witchcraft (1.2.62, 72, 79).[24] I use close-reading activities such as this one to draw students’ attention to the stereotypes about Moors that white men circulate in the play.

I follow this close reading of the play’s opening scene with an examination of Othello and Desdemona’s description of their union in Act 1, Scene 3. As students note, the couple challenge Iago’s portrayal of their relationship by casting Othello as the desired guest and Desdemona as the desiring subject. The contrast between Iago’s representation and Othello’s self-fashioning begin to blur in the play’s later acts as Othello grows more susceptible to manipulation and begins to see himself through Iago’s racist gaze. The change in Othello’s persona makes it easier for students to focus on Othello’s gullibility in the face of Iago’s fabricated evidence about Desdemona and Cassio. I seek to challenge this perspective by asking students to chronicle Othello’s account of the marital, professional, and psychological losses he suffers on account of Iago’s resentment.[25] I do so in order to highlight Othello’s humanity at a point in the play when he appears to be transforming into the violent “other” that Iago envisions for the audience. My task as an instructor is to interrupt audience complicity with characters like Iago and illustrate the methods that he uses to perpetuate racist and misogynist beliefs about Othello and Desdemona until they are echoed by other characters in the play. [27]

One final strategy I use to unpack the play’s racist framework is the exchange between Othello and Emilia that follows Desdemona’s murder in Act 5, Scene 2. Here, Emilia echoes Iago’s language regarding Moors by tarring Othello with a list of racial slurs, including “devil,” blacker devil,” “gull,” and “dolt,” as she proclaims him a murderer (5.2.135, 137, 170). My students’ concern with Othello’s treatment of Desdemona means that they often end up identifying with Emilia, who becomes a proto-feminist heroine of sorts when she outlines the patriarchal double standard that allows men to mistreat their wives (4.3.85–102). This structure of sympathy means that students often end up sharing her critique of Othello as “the blacker devil” just as much as they become complicit with Iago’s stereotypical image of him (5.2.135). In this context, I ask students to consider what Emilia’s words reveal about the politics of race and gender in the play. I want my students to notice that while Emilia is supposed to be subordinate to the men in the play, her racial privilege also gives her greater moral authority over Othello at the play’s conclusion. The final speech we look at is Lodovico’s at the end of the play, which confirms Emilia’s perspective by erasing Othello’s legacy and transferring his wealth to Cassio. Lodovico’s speech demonstrates that, despite their claims of color blindness, the Venetian authorities were always grooming potential heirs from within their ranks in order to reduce Othello’s importance to the state.

Caliban experiences no such fall from grace in The Tempest. His place at the bottom of the social hierarchy is evident to the audience the moment he emerges from the rock where Prospero has imprisoned him. Like Othello, Caliban is described in terms that racialize him, strip him of his humanity, and render him an object of ridicule. In a series of exchanges that we examine in class, Prospero and Miranda refer to Caliban as a “whelp,” “slave,” “villain,” “tortoise,” and “savage” when they first describe him for the audience (2.1.283, 311, 316, 319, 358). Stefano and Trinculo, the drunken butler and jester who become Caliban’s temporary companions on the island, likewise address him as “mooncalf,” “monster,” and “servant monster,” terms that designate his status as an outsider even among those [28] at the bottom of the Neapolitan social ladder (2.2.128, 140; 3.2.3).[26] The epithets used to describe Caliban carry negative associations similar to those about Othello’s skin color and his status as a Moor. The most specific of these designations, surprisingly, comes from Miranda. In her only direct speech to Caliban, the compassion that Miranda shows for the victims of the tempest disappears as she blames Caliban’s “vile race” for his ingratitude toward her father and herself (1.2.361).[27] Caliban seems to confirm Miranda’s perspective of him as a “thing most brutish” when he gleefully admits that he tried to assault Miranda in order to wrest control of the island (1.2.360, 352–54). Miranda’s chastisement of Caliban, coupled with Caliban’s lack of shame about his reported assault on her, sets up a conflict as to whether he deserves to be sentenced to a lifetime of labor and imprisonment. My goal when teaching the play is to foster greater awareness of Caliban’s position by highlighting the similarities between his plans to usurp power and Prospero’s methods for controlling his enemies.

I also invite students to interrogate Prospero’s narrative about his benevolence toward Miranda, Ariel, and Caliban in in Act 1, Scene 2. Students read or perform these scenes in small groups, making note of those moments when Prospero’s performance of kindness appears insincere or unpersuasive. In studying Prospero’s initial speech to Miranda, where he reveals the reasons for their exile on the island, students often comment that Prospero chides her for being inattentive or interrupting him before he puts her into a temporary sleep as he issues his instructions to Ariel (1.2.25–116). Likewise, students note that Prospero shifts from praising Ariel’s skill in raising the tempest that forces his enemies onto the island to threatening Ariel when he demands his freedom (1.2.189-305). Student responses to Prospero’s exchange with Caliban are more complicated; [29] they note that Prospero reserves the harshest criticism for Caliban, whose demand for freedom he counters with a laundry list of the crimes that he has committed (1.2.324–379). I follow this exchange by introducing students to the popular psychological classification of parenting styles as authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive, and then use these categories to interrogate Prospero’s claim that he is a good parent surrounded by ungrateful children (1.2.93–97).[28] Students note that Prospero shifts from the more positive category of authoritative with Miranda, where he is both responsive to questions and rule-oriented, to shades of authoritarianism with Ariel and Caliban, to whose appeals he is unresponsive and rejecting. These popular categories can illustrate the inconsistencies in Prospero’s rhetoric and explain why Ariel, Caliban, and Miranda seek to challenge his authority.

Another method I use to challenge Prospero’s demonizing of Caliban is to examine his relationship with the comic duo of Trinculo and Stefano, which covers Act 2, Scene 2 and Act 3, Scene 2 of the play. We explore these scenes in order to consider Caliban’s political agency when he is outside Prospero’s sphere of influence. In the first scene, Trinculo and Stephano both consider enriching themselves by enslaving and transporting Caliban to Europe (2.2.14-67). In the second scene, Caliban presents a formal petition to Stefano, where he asks him to kill Prospero and promises him ownership of the island and control of Miranda in return for his efforts (3.2.82–98). As we read through these scenes, I ask students to ponder the following questions: What structures of authority inform Trinculo and Stefano’s relationship with Caliban? Does Caliban replace one ruler with another or does this scene reflect his growing agency? What, if anything, does Caliban achieve through his failed rebellion? I use these questions to highlight not only how white privilege empowers Stephano and Trinculo to treat Caliban as their property, but also how their authority [30] is destabilized when they forge an alliance with Caliban. Finally, we examine Caliban’s ambiguous role at the end of the play. Will Caliban be taken to England and displayed as a captive? Will he finally get what he desires and become ruler of the island? In our closing discussion on the play, I have students generate an ending for Caliban. The play, especially when read through a postcolonial lens, affords readers more room to question Prospero’s authority and endows Caliban with more freedom to shape his story.

Visualizing Race/Gender

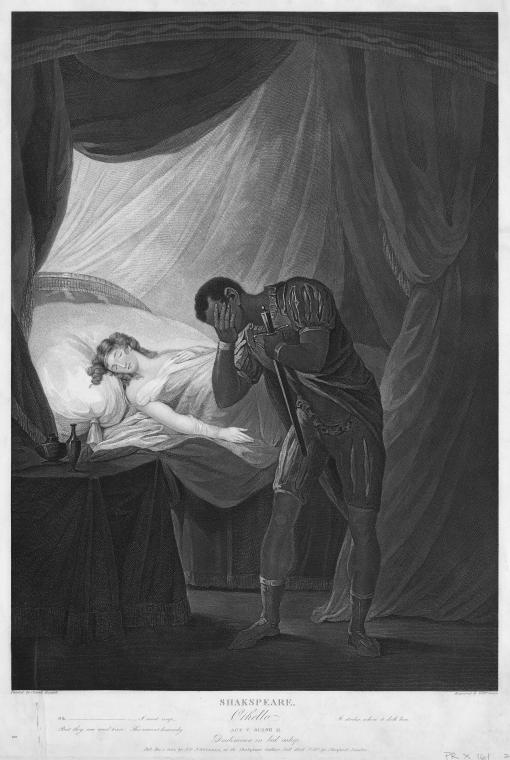

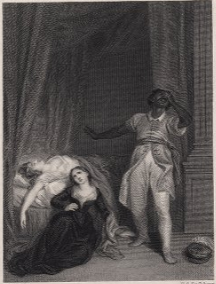

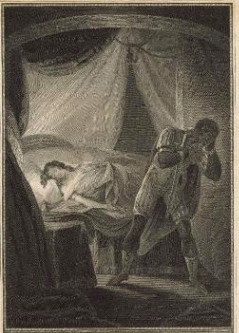

Reading strategies can help complicate the familiar racial stereotypes that can influence students’ reactions to non-white characters. Pairing a close investigation of the text with images that are based on it can also help reveal the manner in which generations of artists have shaped popular responses to the plays. I accordingly conclude class discussion of Othello with two images that are informed by its final scene, George Noble’s engraving of Othello and Desdemona and the John Massey Wright/Timothy Stansfield Engleheart engraving of Othello, Desdemona, and Emilia, both of which were printed in John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, a collection of images from the plays, in 1797.[29] In the first engraving, a shamefaced Othello refuses to look at the sleeping Desdemona before he murders her. In the second, Desdemona and Emilia are situated beside one another while Othello is placed on the margins of the scene.

I display these images after we compare Othello’s final speech, in which he asks the assembled Venetians to measure his service to the state against his misdeeds (5.2.347–366), with Lodovico’s speech, a list of decrees punishing Iago, dividing Othello’s estate, and announcing Cassio’s promotion (5.2.372–382). Lodovico’s primary reference to Othello and Desdemona is a demand that the “tragic loading of this bed” be hidden so that its contents will cease to disturb the viewer (5.2.374). Artistic representations of the play tend to ignore both Othello’s plea and Lodovico’s orders by magnifying the murderous contents of the bed and Othello’s [31] role in producing it. I encourage students to pay close attention to the play of light and shade in these images and consider whose point of view they reproduce. Do they reflect Iago’s negative portrait of the relationship between Othello and Desdemona; Othello’s plea for accurate representation of their union; or Lodovico’s clinical account of their deaths? Students observe that the images come closest to sharing Iago’s perspective on the couple; they do so by situating Desdemona and Emilia in a pool of light while shrouding Othello in darkness as he turns his gaze away from the audience. The visual documents thus perpetuate the erasure of Othello’s status as a noble general by emphasizing the threat that he poses to white femininity.[30]

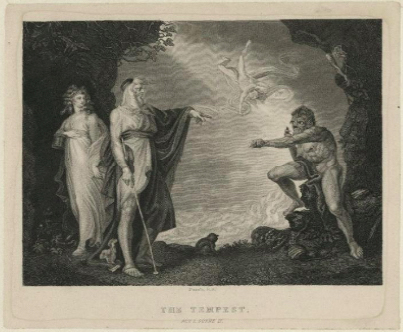

I follow a similar path in discussions of Act 1, Scene 2 of The Tempest by using Henry Fuseli’s popular depiction of Prospero, Miranda, and Caliban, from John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery to enhance our discussion of the play.[31] The engraving features a clothed Prospero with Miranda behind him pointing toward a naked, muscular, and combative Caliban, who crouches aggressively on a rock as Ariel bathed in light looks on from above. I display this image alongside the speech between Prospero, Miranda, and Caliban, which places Prospero’s rhetoric of betrayal by Caliban alongside Caliban’s defense of his actions as a form of resistance to colonization (1.2.324–378). Along with discussing Prospero’s rhetoric in the speech, I ask students to debate whether Prospero has the right to imprison Caliban and whether Caliban has the right to defend himself — even to attack Miranda — in defense of his freedom. Once I have listed students’ responses on the board, I shift the conversation to the image [32] and ask students to consider the following questions: Which aspects of the exchange between Prospero, Miranda, and Caliban does the artist keep, and which ones does he exclude? Why does the artist add Ariel to the scene? How does the artist use light and shadow to distinguish virtuous characters from villainous ones? As students note, the image cements conventional readings by placing Prospero, and Miranda, who are bathed in light, on one side and situating Caliban, who is cast in shadow, on the other. Like the artistic portrayals of Othello, those involving Caliban choose to contrast his interlocutors’ virtue with his inhumanity. Placing images of Othello and Caliban alongside investigations of Shakespeare’s text drives home the message that, far from neutral representations, visual documents can help reinforce the long history of racist representation in which these characters are embedded.

Adaptations of Race/Gender

While artists and filmmakers have often reinforced racist images of Othello and Caliban, twentieth- and twenty-first-century playwrights have a history of resisting such portrayals. In my course, Shakespeare and Race, I assign two adaptations of Othello, Paula Vogel’s Desdemona: The Story of a Handkerchief (1987) and Djanet Sears’ Harlem Duet (1997), and one of The Tempest, Aimé Cesaire’s Une Tempete, or A Tempest (1969). These plays revise Shakespeare’s texts by telling his stories from the perspective of its marginal characters, primarily white women in the case of Vogel, non-white women in the case of Sears, and Caliban in the case of Cesaire. While the adaptations reflect and expand on the source, they are not necessarily utopian alternatives to the race and gender problems that trouble Othello and The Tempest. Reading these texts alongside Shakespeare’s thus allows for a productive conversation on the ways in which racist and sexist tropes are perpetuated and challenged by contemporary writers.

The first adaptation I assign, Paula Vogel’s Desdemona, is a feminist text that centers on the conversations about marriage and sexuality between three female characters from Othello: Desdemona, Emilia, and Bianca. Unlike Shakespeare’s Desdemona, who prefers Othello to her other suitors and remains faithful to him, Vogel’s Desdemona confesses to having enjoyed many lovers before she met Othello and engaging with many [33] more once she is bored with him. She gains access to these lovers through Bianca, a sex worker who helps Desdemona explore her sexual desires by giving her access to her clients.[32] Vogel’s play champions Desdemona’s right to explore her sexual desires but ends up reproducing the problematic racial dynamics of Othello by representing Othello as exotic fodder for his wife’s appetite and a forbidding presence that she ultimately seeks to escape. While the play fulfills many students’ desire for a less submissive heroine by creating a Desdemona who places her desires over her husband’s demands, it also reinforces Shakespeare’s portrait of Othello as the embodiment of Black male jealousy.[33] When I teach the text, I ask students to examine the ways in which Desdemona, Emilia, and Bianca’s roles are expanded as well as the way Othello’s role is limited in the play. These conversations help draw students’ awareness both to Vogel’s refusal to correlate femininity with virtue and her tendency to associate Black masculinity with violence. Desdemona thus offers an important lesson on the pitfalls that writers face when they seek to privilege Othello’s depiction of gender while ignoring its toxic racial politics.

Djanet Sears’s Harlem Duet (1997), a prequel to Othello, provides an important corrective to the erasure of race in Vogel’s text. The play, which is set in Harlem in 1861, 1928, and the 1990s, focuses on the conversations between two composite characters, a Black woman named Billie and a Black man named Othello, who leaves her for a white woman. The majority of the play focuses on the conversations between a grief-stricken Billie [34] who is struggling to come to terms with Othello’s engagement to a white woman named Mona. Billie accuses Othello of marrying Mona out of a desire to erase his racial identity and find acceptance in the white community. Othello rejects her accusation and suggests, instead, that his relationship with Mona and position as a professor at Columbia University are proof that they live in a color-blind world (Act 1, Scene 7). Othello’s claims for assimilation are ironic in this context: the audience is aware that his plans to travel to Cyprus with his wife, Mona, and a colleague, Yago, will result in his death. Harlem Duet draws attention to the contrast between Billie’s fierce attachment to the Black community and Othello’s desire to erase his racial identity. I draw students’ attention to these issues by asking the following questions when we discuss the play: Why does Othello choose to marry Mona when he shows evidence of his continued desire for Billie? To what extent is Othello’s choice dictated by a desire to assimilate to white society? Does Sears’ play share Billie’s point of view that Othello’s quest is futile, and that white acceptance can only be earned through the assertion of Black power? Class discussion of Harlem Duet opens up important conversations about the steep price that members of marginalized communities pay both for their decision to reject the culture of the majority, as Billie does, and for their desire to assimilate to it, as is the case for Othello. Vogel’s Desdemona and Sears’ Harlem Duet are important companion pieces to Othello, since they help reflect on the manner in which Shakespeare’s Desdemona and Othello are trapped by the patriarchal and white supremacist societies to which they belong.[34] [35]

Martinique-born writer Aime Cesaire’s Une Tempete, or A Tempest (1969) performs a similarly important function as Harlem Duet.[35] Written during the twentieth-century movement for decolonization, Cesaire’s play is told from the perspective of Caliban, who is transformed into a revolutionary with the power to raise an army of the island’s flora and fauna to assist him in his battle against Prospero. The narrative also transforms Prospero into the classic colonizer, whose consciousness of the “white man’s burden” compels him to remain on the island and attempt to reassert his authority in the face of Caliban’s revolt. The play ends without victory on either side, with Prospero and Caliban locked in an endless struggle for supremacy. A Tempest is far from balanced: its focus on the battle between Prospero and Caliban, the play gives short shrift to Miranda, who is dismissed by both men.[36] The play nonetheless helps students reflect on the unjust structure of power in Shakespeare’s play and on the colonial regimes that England established in the centuries after it was first performed.

I assign adaptations of Othello and The Tempest to illustrate the ways in which twentieth-and twenty-first-century writers have rewritten Shakespeare in order to address their concerns with his work. The adaptations also demonstrate that Shakespeare’s plays are living artifacts that students can reshape to suit their needs.[37] I present students with the opportunity to engage creatively with the texts they have read through a final project in which they can update Shakespeare for their time. Students have responded to this prompt by rewriting specific scenes and narrative arcs; creating Spotify playlists, Instagram accounts, and TikTok videos for [36] individual characters; activities that are especially useful for reframing discussions of race and gender in Shakespeare.

Discussions that address Shakespeare and race may help students engage with topics that they might otherwise shy away from, but they cannot erase the broader implications of racial bias. Studying the play’s historical context, its racist language, and visual documents, however, will help students reflect more carefully on the interpretive strategies that they use to talk about race in Shakespeare. A layered approach to reading Othello and The Tempest, such as the one I share here, can help students unpack the coded language that is used to demonize its non-white characters and shift sympathy toward their white oppressors. Examining the plays in light of primary documents from the early modern period helps students understand how contemporary discussions about travel, climate, religion, and skin color informed conceptions of character. Likewise, exploring eighteenth- and nineteenth-century images of the plays demonstrates how artists dehumanized Othello and Caliban in a manner that continues to influence popular depictions of the play.[38] Finally, teachers can enhance discussions of Othello and The Tempest by examining adaptations that focus on the perspectives of their marginalized characters. While a set of reading materials may not shift the perspectives on race and gender that students bring to the classroom, they can, nonetheless, challenge conventional modes of reading. By placing historical texts, visual documents, and literary appropriations in conversation with the textual study of Othello and The Tempest, teachers can provide students with the tools to recognize the pernicious effects of racism in the literature they read in class and develop strategies to combat its influence outside the classroom. [37]

Suggested Further Reading

Akhimie, Patricia. Shakespeare and the Cultivation of Difference: Race and Conduct in the Early Modern World. New York: Routledge, 2020.

Chapman, Matthieu. “Away, You Ethiop!”: A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the Denial of Black Affect — A Song to Underscore the Burning of Police Stations.” In Race and Affect in Early Modern English Literature, edited by Carol Meija LaPerle. ACMRS Press, 2022. http://doi.org/10.54027/GJYM2659

Dadabhoy, Ambereen. “The Unbereable Whiteness of Being in Shakespeare.” Postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 11, (2020): 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41280-020-00169-6

Erickson, Peter, and Kim F. Hall. “A New Scholarly Song”: Rereading Early Modern Race.” Shakespeare Quarterly 67, no.1 (Spring 2016): 1–13.

Hendricks, Margo. “Race: A Renaissance Category?” In A New Companion to English Renaissance Literature and Culture, edited by Michael Hattaway, 535–44. 2 vols. New York: Wiley/Blackwell, 2010.

MacDonald, Joyce Green. “Finding Othello’s African Roots through Djanet Sears’s Harlem Duet.” In Approaches to Teaching Shakespeare’s Othello, edited by Peter Erickson and Maurice Hunt, 202–20. New York: Modern Language Association, 2005.

Smith, Ian. “Othello’s Black Handkerchief.” Shakespeare Quarterly 64, no.1 (Spring 2013): 1–25.

Thompson, Ayanna. “Othello/YouTube.” In Shakespeare on Screen: Othello, edited by Sarah Hatchuel and Nathalie Vienne Guerrin, 1–16. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. [38]

Singleton, Henry. Yet I’ll not shed her blood (London: C. Taylor, 1793). Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

John Massey Wright/Timothy Stansfield Engleheart. She loved thee. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

George Noble. Othello, act V, scene 2 (London: J.&J. Boydell, 1800). Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Fuseli, Henry. The Tempest, act I, scene 2. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Johann Heinrich Ramberg, The Tempest, act II, scene 2. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- Carol Mejia LaPerle, “Dark Will, Race, and Affect: Philosophical Histories of Will and Critical Race Studies,” Race and Periodization, Washington DC, 2019. ↵

- Katherine Gillen and Lisa Jennings, “Decolonizing Shakespeare? Towards an Antiracist, Culturally Sustaining Praxis,” The Sundial, 26 Nov. 2019, accessed 27 Jan. 2020, https://medium.com/the-sundial-acmrs/decolonizing-shakespeare-toward-an-antiracist-culturally-sustaining-praxis-904cb9ff8a96. ↵

- Recent legislation against discussions in Florida, Texas, and Oklahoma’s public schools represents just one instance of a broader campaign to suppress antiracist texts and practices. ↵

- I use the term “non-white” when referring to both Othello and Caliban. I am grateful to Matthieu Chapman for his suggestions on terminology. ↵

- David Sterling Brown identifies a similar dynamic in critical responses to The Merchant of Venice and Titus Andronicus in “The ‘Sonic Color Line’: Shakespeare and the Canonization of Sexual Violence against Black Men,” The Sundial, 16 Aug. 2019, accessed 17 March 2021, https://medium.com/the-sundial-acmrs/the-sonic-color-line-shakespeare-and-the-canonization-of-sexual-violence-against-black-men-cb166dca9af8. On the lack of sympathy for Othello’s epilepsy, see Justin P. Shaw, “‘Rub Him About the Temples’: Othello, Disability, and the Failures of Care,” Early Theater 22.2 (2019): 172–173. These essays connect premodern and contemporary methods for policing Black men and can be productively assigned when teaching Othello. ↵

- David Sterling Brown, “(Early) Modern Literature: Crossing the Color-Line,” Radical Teacher (2016): 69–77. ↵

- Kim F. Hall, “Teaching Race and Gender,” Shakespeare Quarterly 47.4 (1996): 461. Eric De Barros makes a related point when he suggests that instructors should find strategies to help students confront their biases instead of seeking to reduce their discomfort with discussing issues of race, “Teacher Trouble: Performing Race in the Majority White Shakespeare Classroom,” Journal of American Studies 54.1 (2020): 79. ↵

- See Robin DiAngelo, “White Fragility,” International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 3.3 (2011): 57. ↵

- On Othello’s resonance for students of color, see Francesca Royster, “Rememorializing Othello: Teaching Othello and the Cultural Memory of Racism,” Approaches to Teaching Shakespeare’s Othello, edited by Peter Erickson (New York: MLA Press, 2005), 53–61. ↵

- Ayanna Thompson, “Did the Concept of Race Exist for Shakespeare and his Contemporaries?” The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Race (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 7–8. Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (New York: Penguin, 2016), 20–21. ↵

- In the preface to his book, Kendi classifies ideas about race into three groups, segregationist, or the belief in racial hierarchies, assimilationist, the belief that marginalized groups should adopt the cultural values of those in power, and antiracist, the belief that all races are equal (4–5). I find it useful to outline these categories and ask students where they would situate the characters in Othello and The Tempest in relation to them. ↵

- The inconsistencies of early modern race-making are also illustrated in Ania Loomba and Jonathan Burton’s anthology, Race in Early Modern England: A Documentary Companion (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). ↵

- All references to the play are from William Shakespeare, Othello: Text and Contexts, ed. Kim F. Hall (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007). The excerpts from “The Lady and the Blackamoor” and Discourse of Discovery that I assign are from the chapter, “Race and Religion,” in the Cultural Contexts section of the volume. ↵

- Hall, 197-203. ↵

- Patricia Fumerton offers an excellent account of the ballad’s recirculation in prose accounts about the threat that enslaved people posed to slaveholders in eighteenth-century Georgia, The Moving Violation of “The Lady and the Blackamoor.” The Broadside Ballad in Early Modern England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 273–274. Excerpts from the prose account might be taught alongside the ballad to illustrate the process by which a sensational work of fiction may be repackaged as a truthful account in the service of race-making. ↵

- Hall, 193. ↵

- All references are from William Shakespeare, The Tempest, edited by Gerald Graff and James Phelan (New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000), 126. ↵

- Graff and Phelan, 120. ↵

- For a discussion of European beliefs about the inhabitants of the Americas and their attitude toward Indigenous property rights respectively, see essays by John Gillies and Patricia Steed in The Tempest and Its Travels edited by Peter Hulme and William H. Sherman (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), 180–219. ↵

- I am grateful to Elisa Oh for outlining the “pre-formed and bone-deep conceptions of race” that students bring to the classroom in the RaceB4Race Symposium, “Race and Periodization,” Washington DC, September 2019. ↵

- On the divergence of Black and white opinion on race and policing, see Ian F. Smith “We are Othello: Speaking of Race in Early Modern Studies,” Shakespeare Quarterly (Spring 2016): 116–117. ↵

- Peggy McIntosh, “White Privilege and Male Privilege,” Privilege: A Reader, ed. Michael Kimmel (New York: Routledge, 2017), 29, 36–37. Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersections of Race and Sex,” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1 (1989): 143, 159. ↵

- For an excellent resource on the way language is used to idealize whiteness and demonize blackness, see Farah Karim-Cooper, “Anti-Racist Shakespeare,” Shakespeare’s Globe, 26 May 2020. www.shakespearesglobe.com/discover/blogs-and-features/2020/05/26/anti-racist-shakespeare. Accessed 10 Jan. 2020. ↵

- I remind students of the content note on my syllabus before we engage in close-reading activities that involve racist language or forms of sexual violence. ↵

- Othello’s exchange with Iago in 3.3.350–379 is instructive in this regard because Othello uses it to connect his loss of Desdemona with his loss of reputation in the Venetian army. ↵

- All quotes are taken from The Tempest: A Case Study in Critical Controversy, eds. Gerald Graff and James Phelan (New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000). ↵

- On the manner in which Caliban is raced, see Matthieu Chapman, “Red, White, and Black: Shakespeare’s The Tempest and the Structuring of Racial Antagonisms in Early Modern England and the New World,” Theatre History Studies, vol. 39 (2020): 8, and Ania Loomba, Shakespeare, Race, and Colonialism (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 35 and ↵

- The American Psychological Association’s description of these categories is available at “Parenting Styles,” https://www.apa.org/act/resources/fact-sheets/parenting-styles (accessed 26 Nov. 2019). For a recent analysis of these categories, see Sofie Kuppens and Eva Ceulemans, “Parenting Styles: A Closer Look at a Well-Known Concept.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 28 (2019): 168–181. ↵

- These images are reprinted in Hall, 7, 17, 178. ↵

- Francesca Royster addresses the gaps in Lodovico’s final speech by asking students to create their own epitaphs for Othello, 59. On Othello’s fear that he will be unable to find a sufficiently sympathetic white narrator to tell his story, see Smith, 112. For an important counter-narrative that highlights the racism directed toward Othello, see the short film, “Dear Mr. Shakespeare,” directed by Shola Amoo, 2017, accessed 5 Nov. 2021, https://vimeo.com/183218909. ↵

- Peter Simon, “The Enchanted Island Before the Cell of Prospero – Prospero, Miranda, Caliban, and Ariel.” The American Edition of Boydell’s Illustrations of the Dramatic Works of Shakespeare (1797), The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed 10 Sept. 2019 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/365591. ↵

- For an instance of Vogel’s intensification of Desdemona’s sexual desires, see Scene 11 where her Desdemona confesses, “I simply lie still there in the darkness taking them all into me. I close my eyes and in the dark of my mind — oh, how I travel,” Desdemona: A Play About a Handkerchief, in Adaptations of Shakespeare, eds. Daniel Fischlin and Mark Fortier (New York: Routledge, 2000), 243. Keith Hamilton Cobb’s play, American Moor (2016), offers an important counter-narrative to Vogel’s reading of Othello and may be taught in conjunction with or as an alternative to Vogel’s text. The play focuses on an African American actor’s desire to humanize Othello for theater audiences who have been subjected to misperceptions of his character by white directors (New York: Methuen, 2020). ↵

- On Desdemona’s treatment of Othello as an exotic “other” and her disappointment at his embracing of Venetian values, see Vogel, Scene 11, 242. ↵

- Toni Morrison’s play, Desdemona (2011) is an excellent adaptation to teach in conjunction with Othello. The play reflects on the events in Othello by adding a number of female characters who are mentioned but never seen in Shakespeare’s play, including Barbary/Sa’ran, Desdemona’s non-white maid; Soun, Othello’s mother; and Madame Brabantio, Desdemona’s mother (London: Oberon Books, 2018). Together, these characters draw attention to both Othello’s violence against Desdemona and Desdemona’s race and class privilege in relation to Barbary and Emilia. ↵

- On Harlem Duet’s engagement with Othello, see Nedda Mehdizadeh, “Othello in Harlem: Transforming Theater in Djanet Sears’s Harlem Duet,” Journal of American Studies 54 (2020): 14. ↵

- On the problems with minimizing Miranda’s role in A Tempest, see Jyotsna Singh, “Caliban versus Miranda: Race and Gender Conflicts in Post-Colonial Writings of The Tempest,” Feminist Readings of Early Modern Culture: Emerging Subjects, Eds. Valerie Traub, M.L. Kaplan, and D. Callaghan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 205–206. ↵

- I also remind students to bring their awareness of racial stereotypes that they have studied to bear on their creative projects, especially if they choose to represent non-white characters in the play. ↵

- On the persistence of racist tropes associated with Othello in the popular podcast, Serial, see Vanessa Corredera, “‘Not a Moor Exactly:’ Shakespeare, Serial, and Modern Constructions of Race,” Shakespeare Quarterly (Spring 2016): 38–40. ↵