Teaching Spenser’s Darkness: Race, Allegory, and the Making of Meaning in The Faerie Queene

Dennis Austin Britton

[print book page number: 67]

I begin classes on Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene where most teachers begin, Spenser’s letter to Raleigh:

SIR knowing how doubtfully all Allegories may be construed, and this booke of mine, which I have entituled the Faery Queene, being a continued Allegory, or darke conceit, I have thought good aswell for avoyding of gealous opinions and miscostructions, as also for your better light in reading thereof, (being so by you commanded,) to discover unto you the general intention and meaning, which in the whole course thereof I have fashioned, without expressing of any particular purposes or by accidents therein occasioned. (714)[1]

Of course, there is much to focus on in the letter to Raleigh, but first on Spenser’s list of things that need to be explained is the allegorical nature of his work.[2] I draw my students’ attention to allegory as “darke conceit” [68] that contains within it the potential for “jealous opinions” and “misconstructions.” Halfway through the opening sentence of the letter, we take time to pause. On the one hand, Spenser’s rendering of poetic figuration as dark is entirely conventional. In The Defense of Poesy, Philip Sidney writes that “there are many mysteries contained in poetry, which of purpose were written darkly, lest by profane wits it should be abused,” while in The Art of English Poesie, George Puttenham offers that allegories produce “a duplicitie of meaning or dissimulation vnder couert and darke intendments.”[3] Darkness as it relates to poetry, figures of speech, and allegory functions somewhat differently in Sidney and Puttenham. While Sidney asserts that darkness is created by poetic figures more generally to safeguard “mysteries” from “profane” wits, Puttenham suggests that “duplicitie of meaning and dissimulation” and darkness are specific to allegory — and with his language of duplicity and dissimulation, we have a useful preamble for later classroom discussions of Duessa. What is common to Sidney, Puttenham, and Spenser, nevertheless, is the link between poetic figuration and darkness, a darkness that certain classes of readers — aided by proper modes of reading and interpretation — can overcome.

I do not assume that my students know what allegory is, nor what it means for Spenser to call it the “darke conceit.” In addition to drawing students’ attention to passages from Sidney and Puttenham, I provide them M. H. Abrams’s trusty definition from A Glossary of Literary Terms: “An allegory is a narrative in which the agents and action, and sometimes the setting as well, are contrived both to make coherent sense on the ‘literal,’ or primary level of signification, and also to signify a second, correlated order agents, concepts, or event.”[4] Abrams’s definition itself requires unpacking, but what I hope students get from Abrams is that allegories tell two stories at once and recall the duplicity described by Puttenham. [69] But I also use Abrams to highlight the fact that there is a story that resides on the literal level, and that that story is worth thinking about on its own terms. While there is nothing particularly radical about asking students to pay attention to the relationships between characters, places, and actions and “agents, concepts, or events,” I want students to consider why a story about knights, ladies, and monsters must be interpreted as signifying the becoming of the White English Protestant nation, how the ideological work of the poem almost forces readers to make certain connections between characters and concepts in order to produce “correct” interpretations of the poem and reject the dark ones.[5]

Interpretation, after all, is a primary source of Spenserian anxiety. If it was obvious that the Fairy Queen should be read as “the most excellent and glorious person of our soveraine the Queene” (716) and that Belphoebe, too, should be read as signifying aspects of Elizabeth I, Spenser would have no need to explain it in the letter. Spenser recognizes that allegories are prone to be interpreted in a manner that departs from the author’s intention. But here, interpretations that depart from those intended by the author point to a reader who is unable to master darkness. Through his letter and his narrator, Spenser seeks to guide the reader toward specific interpretations. As the literary critic Susanne Lindren Wofford puts it, “While the poem textualizes its meanings by directing attention to the openness, instability, and generativity of signs as signs, and to the tropological exchanges within and among signs, the allegory works in an opposed way, putting into action what we might call the narrator’s hegemonic desire to enforce assent to dominant traditional discourses and to the political and social power they affirm.”[6] If Spenser (and the narrator) were to have his way, our teaching of The Faerie Queene might be reduced to helping students do little more than grasp what we presumed to [70] be the poet’s intended meaning, to helping them read his allegory “correctly.” To do this, however, would be grossly out of line with scholarly attention — especially after the influential poststructuralist theorist Roland Barthes killed authors — to various ways that meaning may evade intention, and the ways in which the allegorical mode is unable to maintain exact equivalency between what Renaissance scholar Harry Berger called many years ago the allegorical “Image” and “Idea.”[7] But I want to suggest that resistance to what seems to be Spenser’s intended meaning is all the more necessary for understanding the construction of race in his poem, especially as it emerges in connection to knowledge and interpretation. The letter links “misconstruction” of meaning to the darkness of/in/surrounding the reader. The poem wants to lead readers to the light of “correct” interpretation, which often emerges through vanquishing dark, racialized characters who hold wrong knowledge.[8]

I give my students what seems to be a simple task: trace images of lightness and darkness, whiteness/fairness and blackness, in the poem; chart who and what are associated with light and dark; and pause at moments when the poem mentions objects or activities related to reading and interpretation. This tracing, of course, is assisted by having students read portions of Kim F. Hall’s Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and [71] Gender in Early Modern England.[9] Giving students the task of tracing this imagery is especially useful for engaging Book 1 and its project to differentiate Protestant truth from Catholic falsehood. Doing so, I believe, not only provides students with a concrete activity that offers an entryway into the poem, but it also allows the class to discuss the racialization of knowledge production and interpretation.

Edmund Spenser’s epic is a generator of epistemic whiteness, akin to various projects of racialization wherein, as philosopher George Yancy argues, “whiteness is deemed the transcendental norm, the good, the innocent, the pure, while blackness is the diametrical opposite. This is the twisted fate of the Black body vis-à-vis white forms of disciplinary control, processes of white racist embodied habituation, and epistemic white world-making.”[10] The Faerie Queene, through all of the self-consciousness about its allegory, is a useful site for witnessing the process of “epistemic white world-making,” and for examining how Spenser employs allegory as a form of disciplinary control in order to produce specific kinds of meanings. Analyzing the relationship between allegory and meaning, the literary critic Gordon Teskey argues, “Meaning is an instrument used to exert force on the world as we find it, imposing on the intolerable, chaotic otherness of nature a hierarchal order in which objects appear to have [72] inherent ‘meanings.’”[11] Following Teskey, scholars who work on Spenser are now attending to connections between the messiness of allegorization and racialization. Ross Lerner argues that Spenser’s poem “reveals how the unstable project of racialization must continually fail to reduce individuals and communities to the meanings they are supposed to embody, just as readers of The Faerie Queene will continue to discover the gaps and unassimilable narrative materials that unsettle the poem’s allegorical edifice.”[12] In a similar vein, Benedict S. Robinson writes, “Perhaps the world projected by racial discourse is itself an allegorical fiction. But allegory also surely disrupts the smooth functioning of racial signifiers in the very thoroughness with which it sublimates the physicality of the body.”[13] Both Ross and Robinson suggest that The Faerie Queene is an ideal site for unpacking the illogic of racialization precisely because Spenser’s epic often questions what “seems” and what bodies signify. By examining how the poem’s assignments of lightness and darkness work in the service of fashioning the White/light English Protestant gentleman, I believe students are able to see how one particular project of racial, religious, and national self-definition mandated the darkening of others. I also hope this exercise helps students examine how the poem racializes meaning making and interpretation. My primary aim in this chapter, then, is not only to provide a way to teach how race works in The Faerie Queene, but also to argue that we have a responsibility to provide students with the analytical tools for recognizing the ways Spenser’s epic attempts to train readers how to interpret the world through an epistemology of English Protestant whiteness. [73]

Images of dark and light come up immediately in Book 1, and students may note in the epic invocation that the poet calls on the “holy virgin chief of nyne” (1.Proem.2), Cupid,

And with them eke, O Goddesse heavenly bright,

Mirrour of grace and Majestie divine,

Great Ladie of the greatest Isle, whose light,

Like Phoebus lampe throughout the world doth shine,

Shed they faire beames into my feeble eyen,

And raise my thoughtes too humble and too vile

To thinke of that true glorious type of thine,

The argument of mine afflicted stile:

The which to heare, vouchsafe, O dearest dread a while.

(1.Proem.4)

We begin with Spenser’s following of epic convention. I give them invocations from Homer, Virgil, and Tasso — especially since Spenser mentions them as sources of inspiration — as points of comparison. We focus on Spenser’s deification of Elizabeth and his comparison of her to Phoebus. Without Elizabeth’s “faire beames,” the poet claims his “thoughts” will be “too humble and too vile / To thinke of that true glorious type of thine.” The poet’s own mental processes are highlighted here; without the sovereign’s “light,” a metaphorical rendering of royal favor and approval of his artistic enterprise, the poet, his thoughts, and the poem reside in an implied darkness. It is here that the poem links light and monarchal power, and perhaps to imperial ambition — if we are to believe that Elizabeth’s light, like Phoebus’, shines on the whole world.

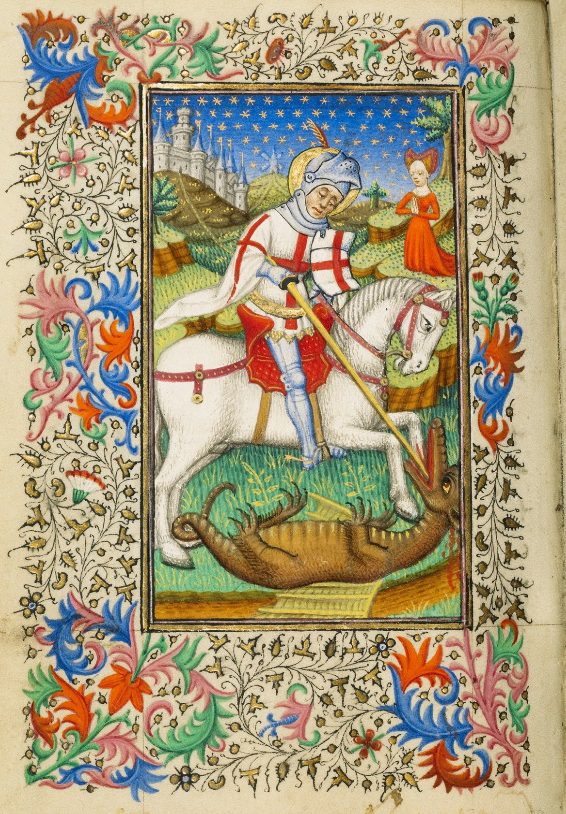

We then move on to the opening stanzas of canto 1 and analyze the description of Redcrosse Knight alongside images of St. George and the Dragon. Both because the poem does not identify Redcrosse as St. George until canto 10 and because most students are unfamiliar with the legend and its iconography, I draw attention to what the description of Redcrosse would likely have called to the minds of Spenser’s first readers. We look at a variety of Medieval and Renaissance images of St. George and the [74] Dragon, including an imaged from an illuminated manuscript by Master of Sir John Folstof (figure 1) and Raphael’s painting (figure 2):[14] [76]

Students notice similarities among representations: the light-reflecting sheen of St. George’s armor, the whiteness of his horse, the whiteness of the princess, her red dress, and the darkness of the dragon. In Master of Sir John Folstof’s image, students will also note similarity between St. George’s breastplate and shield, the St. George’s Cross (though usually identified by them as the English flag), and the description of Redcrosse:

And on his breast a bloudie Crosse he bore,

The deare remembrance of his dying Lord,

For whose sweete sake the glorious badge he wore,

And dead as living ever him ador’d:

Upon his shield the like was also scor’d,

For soveraine hope, which in his helpe he had:

Right faithfull true was in deede and word,

But of his cheere did seeme too solemne sad;

Yet nothing did him dread, but ever was ydrad.

(1.1.2)

It almost appears that Spenser was looking at Master of Sir John Folstof’s illustration when composing Book 1, even to the description of the knight’s “sad” expressions. But what I want students to take away here is a preliminary understanding of iconographic traditions, the way certain stories, characters, people, creatures, and settings are repeatedly represented. Although in many ways meaning presupposes figuration in The Faerie Queene, meaning making is assisted by shared expectations established through generic and iconographic traditions.

Following our analysis of Redcrosse, we discuss Una, in whom the colors black and white come into explicit contact:

A lovely Ladie rode him faire beside,

Upon a lowly Asse more white then snow,

Yet she much whiter, but the same did hide

Under a vele, that wimpled was full low,

And over all a blacke stole shee did throw,

As one that inly mournd: so was she sad

And heavie sat upon her palfrey slow: [77]

Seemed in heart some hidden care she had,

And by her in a line a milkewhite lambe she lad.

(1.1.4)

Una is superlatively white. Here is a good place to ask students to think about the relationship between the literal and the figurative, between the chromatic image they are asked to imagine, and that to which it is supposed to point. Students can easily see that — in a single stanza! — images of whiteness abound, even as they note that the whiteness described is impossible to see/imagine/perceive: how can an ass be whiter than snow, and then how can a woman be whiter than a whiter-than-snow ass? Here Spenser seems obsessed with creating a figure who is whiter than white. But as the imagery asks us to visualize a whiteness that is whiter than white, the description points to something that exist beyond the level of the merely chromatic.

Given the task of charting images of lightness/whiteness and darkness/blackness, students will likely note as well that Una is covered by a “black stole.” Upon this recognition, Una’s special allegorical status becomes evident — not all characters in the poem exist on the same allegorical level. By way of the black stole, Spenser teaches the reader how to interpret the color of surfaces. While wearing black garments is certainly a conventional sign of mourning, the narrator makes it a point to inform us that she wears the black stole “As one that inly mournd.” The narrator, as Spenser does in the letter to Raleigh, wants to make sure readers interpret correctly and isn’t content to leave interpretation solely to the reader’s ability to decipher color symbolism. Una becomes a figure for allegory itself; she is covered by darkness that the reader must see beyond to understand the truth she represents, even as the outer, surface layer points toward something internal.[15] [78]

I will also ask students what it means that Una sits “faire beside” Redcrosse. Does “fair” describe Una’s appearance or the manner in which she rides? Here is another good place to direct students to Hall’s Things of Darkness and the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), where they will encounter a dizzying number of definitions for “fair” as an adjective, any number of which might be in play here: for example, “Beautiful to the eye; of attractive appearance; good-looking” (def. A.I.1), “Excellent, admirable; good, desirable; noble, honourable; reputable” (def. A.I.6), “Expressing or expressive of gentleness or peaceable intention; kind, mild” (def. A.II.8), “Open to view, plainly visible; clear, distinct” (def. A.II.9.b), “In accordance with propriety; appropriate, fitting; seemly, becoming” (def. A.II.13), and “Of hair or complexion: light as opposed to dark in colour. Of a person: having such colouring” (def. A.IV.17). Arguably, however, these varied meanings all bear on Una’s characterization; although there are multiple ways to read “faire besides,” all understandings of fair adhere to each other in Una’s oneness. She is White because she is fair in her looks, character, and behaviors.

It is worth me saying quite explicitly here that the arguments and assertions above are based on a conviction that projects of racialization are variously aligned with, contained in, and transmitted through iconographic traditions, Christian typology, conventional color symbolism, and generic/poetic conventions.[16] Moreover, I assert, The Faerie Queene does [79] not simply employ these; it produces hermeneutics, or modes of interpretation, that shape how readers read. It works to make the color “white” appear “fair” — in all senses of the word, as described above — by repeatedly darkening people, places, and concepts. For example, using a simile to apologize for telling the story of Paridell and Helenore in Book 3, the narrator notes that evil examples are useful, “As white seemes fairer, match with blacke attone” (3.9.2). We might well ask how something can appear visually fairer than white; the simile suggests that the fairness of whiteness can only be perceived through its relationship to blackness — a perception that critical race studies has variously illuminated. As such, Spenser’s project needs blackness; just as whiteness cannot seem fair based solely on its chromatic quality, the fairness of English Protestants and the values they hold is only perceptible with the aid of blackness.

All of this becomes especially evident when Redcrosse and Una encounter Errour. Given the poem’s very careful uses of light and dark, the sudden tempest and darkening of the sky that leads Redcrosse, Una, and the dwarf “to seeke some covert nigh at hand” in “A shadie grove” (1.1.7) signals the character’s movement into a deeply allegorical space. But as they encounter Errour and the darkness surrounding her character, the reader also encounters what I suggest is the poem’s first explicit racialization of knowledge. The dwarf suggests that it would be best to leave Errour alone, “Fly fly (quoth then / The fearefull Dwarfe:) this is no place for living men” (1.1.13),

But Full of fire and greedy hardiment,

The youthfull knight could not for ought be staide,

But forth unto the darksom hole he went,

And looked in: his glistering armor made

A little glooming light, much like a shade,

By which he saw the ugly monster plaine,

Halfe like a serpent horribly displaide, [80]

But th’other halfe did womans shape retaine,

Most loathsome, filthie, foule, and full of vile disdaine.

(1.1.14)

Redcrosse’s light is not as strong as it should be, and in noting that his “glooming light” is “much like a shade,” the narrator may even suggest that there is a degree of darkness within him.[17] Dark as his light may be, it nevertheless allows Redcrosse to see the “ugly monster plaine.” Here is another place to have students consult the OED, which will allow them to see that Spenser’s use of “plaine” is anything but plain. Yet, what is perhaps the most obvious understanding of “plaine” — “Clear to the senses or the mind; evident, manifest, obvious; easily perceivable or recognizable” (OED, plain adj. 2. III.7) — is also the most nonsensical: how is Redcrosse able to see Errour clearly or plainly in the dark? That “plaine” should primarily be read in this way is also suggested by the usage of the word in stanza 16: “For light she hated as deadly bale, / Ay wont in desert darknes to remaine, / Where plain none might her see, nor she see any plaine” (1.1.16). Errour resides in the darkness so that she does not have to be seen or see others — she’s minding her own business! Here again, students see how darkness is meant to obscure clarity: surprisingly, Errour, like Una, becomes a figure for allegory itself.

Errour as a figure for allegory, however, is more explicitly linked to issues of interpretation, especially since “plaine” can also mean “Of which the meaning is evident; simple, easily intelligible, readily understood” (OED, plain adj. 2. III.9.a). Considering this meaning of “plaine,” perhaps Errour is a figure that is easily understood even if she is not clearly seen. For those of us interested in the workings of ideology and White supremacy, the troubling implications of this formulation are apparent: what is already understood to be true has little to do with what is really there and is placed in the shadows. There is no need for Redcrosse or the White Protestant reader to really see Errour because she already signifies error; all that really seems to matter is what she already means within the allegory, what is “easily intelligible, readily understood.” [81]

That Errour is a figure related to meaning making and interpretation is also emphasized in her connection to books. After Redcross “grypt her gorge,”

Therewith she spewd out of her filthie maw

A floud of poyson horrible and blacke,

Full of great lumps of flesh and gobbets raw,

Which stunck so vildly, that it forst him slacke

His grasping hold, and from her turne him backe:

Her vomit full of bookes and papers was,

With loathly frogs and toades, which eyes did lacke,

And creeping sought way in the weedy gras:

Her filthy parbreake all the place defiled has.

(1.1.20)

Errour’s blackness is internal — a few stanzas later readers learn that she has “cole black blood” (1.1.24) that nearly overwhelms Redcrosse. We also see that this blackness is comprised of “books and papers” and blind “frogs and toades.” Editor A. C. Hamilton’s gloss makes it clear that here we are supposed to see Errour and the filth she spews as signifying the Roman Catholic Church and its doctrines.[18] The oddness of Errour’s vomit itself signals that we should read allegorically, and there is little reason not to read Errour as figuring Roman Catholicism — the blindness of Errour’s children can certainly be interpreted as pointing to what Protestants saw as the Roman Catholic refusal or inability to accept the truth. Yet, what I want students to consider here, again, are the bodies in which ideas and concepts are lodged — and the details attributed to those bodies matter. Errour is seen as dark, even if it is only because she resides in the shadows, her internal fluids are black, and a few stanzas later we learn that she has serpent children who are “Deformed monsters, fowle, and blacke as inke” (1.1.23). If Una is the whitest character in The Faerie Queene, Errour is the blackest. [82]

The narrator continues to demonize Errour through an epic simile in Stanza 21:

As when old father Nilus gins to swell

With timely pride above the Aegyptian vale,

His fattie waves doe fertile slime outwell,

And overflow each plaine and lowly dale:

But when his later spring gins to avale,

Huge heapes of mudd he leaves, wherein there breed

Ten thousand kindes of creatures partly male

And partly femall of his fruitful seed;

Such ugly monstrous shapes elswher may no man reed.

(1.1.21)

We stop and pay attention to the first of many epic similes in the poem — indeed, one of my teachers taught me to pay special attention to the political and ideological work done through epic similes.[19] I ask, is it significant that the poem’s first epic simile points toward Egypt and Africa? What connections might the poem be making between Errour/error and Africanness? And, although when it comes to metaphors and similes, we tend to read the vehicle as describing the tenor, to what extent does the tenor denigrate the vehicle — does Errour’s blackness blacken an Africa that in many ways was already understood as Black?

When Spenser needs an image of black monstrous fecundity, he turns to Africa. This turning can be illuminated by Kim Hall’s aforementioned discussion of “trope of blackness”: the use of the trope could be “applied not only to dark-skinned Africans but to Native Americans, Indians, Spanish and even Irish and Welsh as groups that needed to be marked as [83] ‘other.’ However, … in these instances it still draws its power from England’s ongoing negotiations of African difference and from the implied color comparison therein.”[20] Africa was already metonymic for various types of otherness that were rendered visibly Black. In Spenser’s simile, Errour’s blackness aligns with African blackness — and African blackness does not need to be mentioned outright because it is already assumed. In many ways, Errour herself seems to be African: they both are associated with liquidness, and while the Nile produces “such ugly monstrous shapes elswher may no man reed,” Errour’s children are described as “Deformed monsters, fowle, and blacke as inke.”[21]

Errour and Africa are yoked further through the language of reading, texts, and printing: the Nile produces shapes (characters, if you will) that can only be read there, and Errour vomits books and papers and has children “blacke as inke.” Literary critic Miles P. Grier’s discussion of “inkface” is especially useful here. Noting that “black as ink” was a common simile in the early modern period, Grier argues, “By relating the histories of racial thought and the technologies of reading and writing, the inkface concept enables a rich account of performances of literacy as rituals of an elastic racial category of illiterate, legible blacks” and “to link a person to ink was to designate her as one who could never be an insightful reader because she was meant to be read by a white expert.”[22] In Spenser’s allegory, Errour becomes a figure of ill-literacy, producer of both corrupted [84] texts and interpretation. At the same time, the poem’s allegory works hard to make Errour legible vis-à-vis Africa, virtually insisting that English readers focus on what Errour and Africa produce while making sure that they are read with disgust and as absolutely unlike the texts that they encounter “elswher.” Black corporality becomes textuality, made legible through figuration; the religious allegory necessitates a particular reading, and the epic simile that finds numerous correspondences between the allegorical “Image” — to use Harry Berger’s language here again — and the simile’s vehicle shape how the vehicle is itself read. Within the religious allegory, Africa informs how Errour is to be read, and Errour informs how Africa is to be read. I am thus arguing that here Spenser’s allegory quite deliberately invokes Africa as a cite of legible illegibility. Spenser’s yoking of images of blackness with the reference to Africa itself tell us that Africa and blackness can be yoked together, and that in this yoking they produce an image of that which is to be understood as signifying that which is “other” to epistemologies of whiteness. And, more to the purpose of this article, this is worth exploring with our students; we can use texts like The Faerie Queene not only to examine constructions of racial difference in late-sixteenth-century England, but also to show students how texts attempt to train readers to read through racial epistemologies.

Of course, there are many more episodes in The Faerie Queene where students can see how the allegory seemingly requires the application of light/white and dark/black to characters. But this examination of Book 1, canto 1 shows that tracing this chromatic application can help students see reading and interpretation as racializing practices; via allegory, an epistemology of whiteness dictates how literary characters are read, even as the very act of reading the allegory trains readers in that epistemology. This is not to say that differences between “Image” and “Idea” do not problematize the ways the allegory produces this epistemology. The varied critical conversations about such difference in fact make The Faerie Queene an ideal site for witnessing the incoherence of racist epistemologies. Providing students with a deeper understanding of literary genre, mode, forms, and tropes — with which Spenserians have traditionally been obsessed — gives students tools for dissecting how racist epistemologies work, and how they produce the conditions that determine how people are colored and then read. [85]

Discussion Questions

- In what ways does the poem racialize men and women differently?

- The Faerie Queene contains numerous non-human characters like Errour. How are racialized identities shaped through the relationships between humans and non-humans?

- Spenser’s Faerie Queene is an epic poem. Why might epic be an especially fitting genre to help define racial identity?

Further Reading

Britton, Dennis Austin, and Kimberly Anne Coles. “Spenser and Race: An Introduction.” Special issue, “Spenser and Race,” edited by Dennis Austin Britton and Kimberly Anne Coles. Spenser Studies 35 (2021): 1–19.

Chapman, Matthieu. “Staging Blackness: The Impossibility of Interlocution.” In Anti-Black Racism in Early Modern English Drama: The Other “Other,” 33–66. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Hall, Kim F. “Beauty and the Beast of Whiteness: Teaching Race and Gender.” Shakespeare Quarterly 47 (1996): 461–75.

Sanchez, Melissa E. “‘To Giue Faire Colour’: Sexuality, Courtesy, and Whiteness in The Faerie Queene.” “Spenser and Race,” edited by Dennis Austin Britton and Kimberly Anne Coles. Spenser Studies 35 (2021): 245–84.

Thompson, Ayanna. “Afterword: Me, The Faerie Queene, and Critical Race Theory.” Special issue, “Spenser and Race,” edited by Dennis Austin Britton and Kimberly Anne Coles. Spenser Studies 35 (2021): 285–90.

- All quotations from The Faerie Queene are from Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene, edited by A. C. Hamilton, second edition (New York: Routledge, 2001). Parenthetical citation will appear in the essay. Letterforms have been modernized (i/j and u/v), but original spellings have been maintained. Spelling was not fixed in the early modern period, but Spenser uses archaic spellings and words to represent his poem as an artifact from the past. ↵

- We also spend time discussing Spenser’s claims that “The generall end therefore of all the booke is to fashion a gentleman or noble person in vertuous and gentle discipline” (714). As I describe in this chapter, I ask students to think about the ways in which English gentlemen are being fashioned in opposition to “dark” characters in the poem. I also discuss Spenser’s sources, especially Orlando Furioso and Gerusalemme liberata, to draw attention to the ways they represent conflicts between Christians and Muslims. ↵

- Philip Sidney, The Defense of Poesy, in Sir Philip Sidney: Selected Prose and Poetry, edited by Robert Kimbrough, second edition (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983), 99–158, at 157; and George Puttenham, The Art of English Poesy: A Critical Edition, edited by Frank Whigham and Wayne A. Rebhorn (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007), 238. ↵

- M. H. Abrams, A Glossary of Literary Terms, fourth edition (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Watson, 1981), 4. ↵

- I deliberately capitalize “White” following the suggestion of the historian Nell Irvin Painter and others who argue that doing so draws attention to White as a racialized identity. See Painter’s “Capitalize ‘White’, Too,” The Washington Post, July 7, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/07/22/why-white-should-be-capitalized/. ↵

- Susanne Lindgren Wofford, The Choice of Achilles: The Ideology of Figure in the Epic (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992), 222. ↵

- Harry Berger, The Allegorical Temper: Vision and Reality in Book 2 of Spenser’s Faerie Queene (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957), 22. On tensions, contradictions, and polysemy within the allegory, also see, for example, James Norhnberg, The Analogy of The Faerie Queene (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977); Wofford, The Choice of Achilles; Gordon Teskey, Allegory and Violence (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996); and Judith H. Anderson, Reading the Allegorical Intertext: Chaucer, Shakespeare, Spenser, and Milton (New York: Fordham University Press, 2011). Guiding students solely toward “intended meaning” would also ignore the self-consciousness that literary critics often read as inherent to the poem. ↵

- Here we might think about Acrasia’s Bower of Bliss, which since Stephen Greenblatt has been read as pointing toward the Americas. See Greenblatt’s “To Fashion a Gentleman: Spenser and the Destruction of the Bower of Bliss” in Renaissance Self-Fashioning (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 157–92; David Read, Temperate Conquests; Spenser and the Spanish New World (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2000); and Joan Pong Linton, Romance of the New World: Gender and the Literary Formations of English Colonialism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006). ↵

- Kim F. Hall, Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995). I rarely teach The Faerie Queene outside of a sophomore-level Medieval-Renaissance survey. In that course, I might only assign a few pages from Hall’s introduction. But just asking students to read, and then discussing, a few pages is enough to provide an elementary understanding of how race is constructed through images of fairness and darkness. ↵

- George Yancy, Black Bodies, White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race in America, second edition (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 3. Yancy’s focus on White worldmaking is especially evocative here given critical interest in Spenser’s worldmaking. See, for example, Patrick Cheney and Lauren Silberman, eds., Worldmaking Spenser: Explorations in the Early Modern Age (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2000), especially essays by Elizabeth Jane Bellamy, David J. Baker, and Heather Dubrow in sections “Policing Self and Other: Spenser, the Colonial, and the Criminal.” On worldmaking in early modern Europe in Spenser and beyond, and worldmaking as precursor to European imperialism, see Ayesha Ramachandran, The Worldmakers: Global Imagining in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). ↵

- Gordon Teskey, 2. Teskey focuses on how this violence plays itself out in relation to gender. ↵

- Ross Lerner, “Allegorization and Racialization in The Faerie Queene,” in the special issue “Spenser and Race,” edited by Dennis Austin Britton and Kimberly Anne Coles, Spenser Studies 35 (2021): 107–32, at 124. ↵

- Benedict S. Robinson, “‘Swarth’ Phantastes: Race, Body and Soul in The Faerie Queene,” in the special issue “Spenser and Race,” edited by Dennis Austin Britton and Kimberly Anne Coles, Spenser Studies 35 (2021): 133–51, at 134. ↵

- Both images have a specific English connection. The Master of Sir John Folstof gets his name from the manuscript he illuminated belonging to Sir John Folstof. In Raphael’s painting, St. George wears the blue garter of the English Order of the Garter with the order’s motto, HONI (Honi soit qui mal y pense, disgraced be he who thinks ill of it). The painting was made for King Henry VII’s emissary, Gilbert Talbot. ↵

- This reading is also supported by the editor’s, A. C. Hamilton’s, gloss: “by more white then snow with truth (in Ripa 1603:501, Verità is vestita di color bianco) and with faith cf. x 13.1); and by her vele with the truth that remains veiled to the fallen” (32, note to stanza 4). And yet, Spenser’s figure of truth is not clothed in white, but is white herself clothed in black, a distinction that is worth asking students to consider. Nonetheless, the gloss echoes Sidney’s suggestion that poetic figuration conceals the truth from those for whom it is not intended. Hamilton also cites the art historian Roy Strong, who notes that black and white are traditionally the colors associated with perpetual virginity, and thus this depiction of Una also points toward Elizabeth I. On the significance of the relationship between Una’s whiteness and her black stole that is complementary to my own, see Robinson, “‘Swarth’ Phantates,” 145–46. Robinson, as I do below, also suggests that we read this in relation to a later moment in the poem when the narrator tells us “As white seemes fairer, match with blacke attone” (3.9.2). ↵

- Kimberly Anne Coles and I have argued, “The question is not whether whiteness or blackness is attached to actual bodies that are white or black: the question is whether this moral encoding attaches at all. And what happens when we entertain the possibility that it might?” (“Beyond the Pale,” Spenser Review 50.1.5 [Winter 2020]. http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/spenseronline/review/item/50.1.5. Accessed February 13, 2021). In the article we posed this as a question of “possibility” because we were writing to an audience of skeptical, if not hostile, Spenserians. Nevertheless, Coles and I are certain that this moral encoding does attach to real bodies in the early modern period. ↵

- Hamilton suggests this in his gloss (34, note to stanza 14). ↵

- Hamilton, 36 note to stanza 20. ↵

- My classes with Susanne L. Wofford have greatly influenced how I read The Faerie Queene. Considering this simile, she writes, “In contrast to the allegory’s tendencies as an extended metaphor to make its divergent material seem to have a deeper ‘affinitie,’ the similes often insinuate a suppressed interpretation that the allegory does not easily countenance” (291). Wofford sees this at work in the fact that while Redcrosse is surely meant to defeat error, Errour as breeder creator of books and paper’s and strangeness makes her a figure of the poem itself. ↵

- Hall, Things of Darkness, 7. ↵

- We also take time to discuss Errour’s gender, dangerous fecundity, and reproductive capacity and capability. The groundbreaking work on race in early modern texts by Kim F. Hall, Ania Loomba, Margo Hendricks, Patricia Parker, Francesca Royster, Arthur Little Jr., and Joyce Green MacDonald has shown us the varied ways in which race was constructed through and alongside gender discourse. ↵

- Miles P. Grier, “Inkface: The Slave Stigma in England’s Early Imperial Imagination,” in Scripturalizing the Human: The Written as the Political, edited by Vincent L. Wimbush (New York: Routledge, 2015), 193–220, at 195. Playing on the relationship between character as a symbol that represents language and as distinguishing features of a person’s or people’s mental or moral qualities, Grier also asserts that “Inkface, the metonymic play that represents ‘blackness’ as marked signifiers in a European characterology, was critical to an early modern English imperial project” (196). ↵