Teaching Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko as Execution Narrative

Jennifer Lodine-Chaffey

[print edition page number: 87]

[1] Aphra Behn’s 1688 novella Oroonoko, or The Royal Slave offers high school and post-secondary teachers a unique opportunity to explore late-seventeenth-century race relations with their students. As a semi-autobiographical piece written by an Englishwoman, Oroonoko draws readers in through its sympathetic treatment of the enslaved African prince and his wife, Imoinda. Recent scholarly articles have stressed the usefulness of this text for teaching about racism, seventeenth-century travel narratives, and representations of gender.[2] While these are valuable ways to engage with the text, I want to suggest a further option. By looking closely at Behn’s depiction of Oroonoko’s execution, we can further students’ understanding of the construction of race relations through the lens of execution practices in the New World.

Written as both a romantic court intrigue narrative and an “eye-witness” account of British colonial practices in Surinam (which they occupied from 1650 to 1667), Oroonoko tells the story of an African prince’s life, enslavement, and horrific death. Aphra Behn (1640–1689), a Restoration-era [88] English dramatist and poet and one of the first British women to make a living by her pen, recounts Oroonoko’s tragic fall in a narrative that traces his love for and loss of the beautiful Imoinda, enslavement through trickery, sale to colonists in Surinam, rebellion against his British owners, and eventual execution. Perhaps the most striking/shocking passage of the novel is the scene of Oroonoko’s death. In gruesome language, Behn relates that as the African prince tranquilly smokes a pipe, his body is progressively dismembered:

[T]he Executioner came, and first cut off his Members [genitals], and threw them into the Fire; after that, with an ill-favoured Knife, they cut his Ears, and his Nose, and burn’d them; he still Smoak’d on, as if nothing had touch’d him; then they hack’d off one of his Arms, and still he bore up, and held his Pipe; but at the cutting off the other Arm, his Head sunk, and his pipe drop’d, and he gave up the Ghost, without a Groan, or a Reproach.[3]

What strikes the reader about this account is not just the violence enacted on the slave’s body, but the curious lack of reaction to physical pain displayed by Oroonoko himself. Despite the intense physical agony he must be experiencing, the prince refuses to give voice to his torture.

Students are often shocked by Behn’s description of Oroonoko’s execution and the prince’s stoic behavior.[4] In our contemporary society, [89] instructors at all levels should consider the possibility that some students may find the gruesome violence enacted upon Behn’s central character not only shocking, but also viscerally disturbing. While I believe that Behn intends Oroonoko’s execution to alarm and upset the reader in order to evoke sympathy for the executed prince, instructors may want to consider providing some warning about representations of violence and their potential impacts before analyzing capital punishments in the early modern period. However, providing full trigger warnings, as ethnicity and gender theorist Jack Halberstam argues, “reduces the viewer to a defenceless, passive, and inert spectator who has no barriers between herself and the flow of images that populate her world.”[5] Indeed, while it is important to be sensitive to individuals in our classrooms, it is also imperative that students confront our shared historical past. The power of teaching works that represent violence like Behn’s Oroonoko, I argue, is that it encourages reflection on human morality and mortality and it asks us to interrogate values in the past and today. Additionally, students should understand that violence against black bodies in historical sources and literary texts is related to and implicated in twenty-first-century racism.

With these provisos, I seek to move beyond the initial shock of the final scene in Behn’s Oroonoko to analyze the importance of execution rituals and question why these practices mattered in the greater Caribbean world.[6] In my class and throughout this essay, I focus on the connections between racism and corporal punishment in order to re-examine the history and origins of antiblack oppression. In particular, Behn’s novella explicitly links execution and racial formation, thereby highlighting the disproportional historical punishment of people of color, which students must grapple with not only in my class but also in our modern world.To provide students with a grasp of execution theory and practice so they [90] can more readibly think through the connections between race and punishment, I assign supplementary readings that help guide our discussions of Oroonoko’s death and its possible meanings. These readings include primary source documents about British executions in London during the seventeenth century, an article by noted historian Richard Price about Surinam slave punishments that contains a contemporary account of a slave execution, and a short reading from theorist Michel Foucault about executions from his influential study Discipline and Punish. In addition, I ask students to put these sources in conversation and individually work on theorizing Oroonoko’s behavior in writing before attending a class session that breaks students into groups to jointly work on the possible meanings of Oroonoko’s execution in Behn’s text. Finally, students are asked to consider poet and engraver William Blake’s images of slaves undergoing punishment included in John Gabriel Stedman’s 1796 Narrative, of a Five Years’ Expedition, against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam. By focusing on Oroonoko’s execution and Blake’s engravings, students begin to question their own ideas about slavery and race relations during the long eighteenth century.

Most twenty-first-century students initially come to Oroonoko with fixed ideas about slavery based on more recent American history. Often informed by master narratives about slavery and its connection to Southern cotton plantations and general assumptions that all “good” people viewed slavery as morally wrong, students tend to initially read Behn’s text as containing an abolitionist message and assume that resistance to slavery is based on the belief that slavery is inherently evil. Their prolonged engagement with Oroonoko, however, complicates this simplistic reading. My hope is for students to gain important realizations about Behn’s novella that provide them with greater understanding of historical slavery and racism, how early modern depictions of Black peoples usually reinforced ideologies of white racial dominance, the importance of the Caribbean world in the slave trade, and the racial construction of execution practice that contributed to the growth of later prejudices. [91]

Establishing Historical Context: Assigned Readings

To obtain a broader understanding of how executions worked in seventeenth-century Great Britain, I assign the anonymous account of John Marketman’s 1680 hanging. This document not only details Marketman’s murder of his wife, but also describes his final actions before death. What I hope students gain from this text is that for the common British man or woman, public executions generally included a number of rituals missing from the accounts of Afro-Caribbean slave executions. For instance, the condemned in Britain received religious instruction and were expected to express sinfulness and repentance on the scaffold. Often narratives noted sympathetic reactions from the audience. In contrast to Oroonoko, the account of Marketman’s execution focuses not on the grisly details of his death, but instead on his remorse. According to the anonymous author, in his “long speech,” Marketman lamented his disobedience to his parents, his “Youthful days [spent] in Profanation of the Sabbath,” his “Debaucheries beyond expression,” and his failure to emulate his wife’s virtuous behavior. Notably, Marketman ended his last statement by asking that “all should pray to the Eternal God for His everlasting welfare,” and “[recommending] his Soul to the Almighty.”[7] His scaffold speech, which humanizes Marketman by alluding to his spiritual condition and familial ties, is typical of many accounts during this time period and is readily available from the database of scanned primary sources, Early English Books Online.[8] [92]

To further students’ understanding not only of typical British executions, but also executions in the New World, and their intersections with race and with the way the British punished Black slaves in the New World, I include an online article from the historian, Richard Price. In “Violence and Hope in a Space of Death: Paramaribo,” Price explains the gruesome 1710 dismemberment and capital punishment of a runaway slave as seen through the eyes of J. D. Herlein, a Dutch traveler. Quoting Herlein, Price describes the execution of the man in vivid detail:

He was lain on the ground, his head on a long beam. The first blow he was given, on the abdomen, burst his bladder open, yet he uttered not the least sound; the second blow with the axe he tried to deflect with his hand, but it gashed the hand and upper belly, again without his uttering a sound. The slave men and women laughed at this, saying to one another, ‘This is a man!’ Finally, the third blow, on the chest, killed him. His head was cut off and the body cut in four pieces and dumped in the river.[9] [93]

I suggest that students connect this anonymous slave’s execution behavior to Oroonoko’s conduct and notice that both enslaved individuals refuse to give voice to their pain, and that neither account provides the last dying speech their contemporaries in Great Britain usually delivered. In addition, this text stresses the reactions of the crowd, who applaud the dying man’s stoicism. While this detail is not present in Behn’s text, the “slave men and women” watching the execution in Herlein’s account attest to the bravery of the victim, suggesting that his silence is heroic and a sign of courage, and in this case, manliness.[10]

Finally, I add to this short packet a section from theorist Michel Foucault’s seminal work that presents his interpretation of public execution as a “theatre of punishment” where the state inscribes its power on the body of the criminal and forces him or her to confess and repent. For Foucault, the executed body attests to the truth of the sentence and the ritual of execution belongs “to the ceremonies by which power is manifested.”[11] The political display of the tortured body and death of the condemned affirmed the power of the sovereign through “a policy of terror,” meant to reassert the monarch’s power over the physical bodies of his subjects. For Foucault, executions publicized the ruler’s authority and worked to instill the people’s fear and obedience. Likewise, the last dying speeches of the condemned authenticated the sentence of the law.[12] Foucault also argues that torture needs to meet three conditions: it must produce measurable pain, it should mark the victim physically, and it needs to “form part of a ritual.”[13] I encourage students to question Oroonoko’s execution in light of these theories and to ask themselves two questions: does [94] Oroonoko’s tortured body function as a sign of the planters’ authority? And does Oroonoko’s refusal to acknowledge his suffering diminish the torture he and the reader experience? By asking these questions, students confront the violence enacted on Oroonoko not only as a clear racializing of Black bodies through execution practices, but also as evidence of the ways that literature and the visual arts influenced and continue to influence the dehumanization and objectication of Black individuals.

Theorizing Colonial Executions of Enslaved Individuals: Assignment and Discussion

Three class days are spent on the text of Oroonoko. The first day is a general introduction to Aphra Behn’s writings and biography, as well as a guided discussion of the first half of the novella. This class discussion will include questions of genre, as well as an overview of themes of nobility, slavery, and the colonial project. At the end of this class, I provide the students with a collection of documents (including Marketman’s execution narrative, Price’s article, and a chapter from Foucault’s seminal work) to consider in conjunction with Behn’s novel. I ask them to carefully read these short pieces and write/craft answers to the following questions:

- How is Oroonoko’s execution different from the 1680 execution of John Marketman? How is it the same?

- What do you notice about Herlein’s description of the 1710 execution of a runaway slave in Paramaribo? How is this execution similar to or different from Oroonoko’s execution?

- What is Price’s central argument about slave executions? Do you agree or disagree?

- How does Foucault interpret execution? How might we apply these ideas to Oroonoko’s actions during his public punishment and subsequent execution?

- Why do you think Behn depicts Oroonoko as a silent sufferer? Why doesn’t he cry out during his sufferings?

During the second class period, students meet in groups of three to five to compare notes and come up with possible reasons for Oroonoko’s execution [95] behavior and jointly answer the five questions I posed. I spend time visiting with each group to ascertain their involvement with the supplementary materials, Behn’s text, and the questions. I ask each group to turn in their answers at the end of the class period.

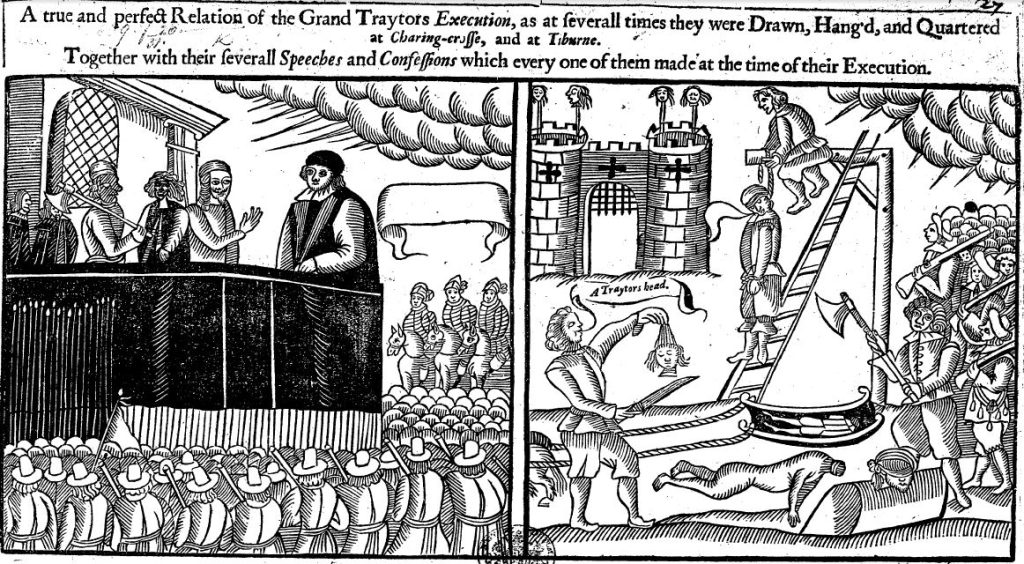

During the third class period focusing on Oroonoko, I go through the students’ answers in class and present differing views of the prince’s execution behavior based on student analysis. In this way, students become active participants in the classroom, guiding the discussion and offering historically and theoretically informed interpretations of Oroonoko based on the assigned readings. This session thus uses a dialogic approach that takes into account both the students’ response and my own approach to the text. Building on this opening exercise, I present a guided lecture with relevant artwork. I thereby provide students with further examples of both British executions and Caribbean slave executions and outline the differences in practice between the Old and the New World. With my students’ assistance, I break down the different representations, noting the preparation for death and the expectation of a final speech for contemporary British men and women. I also provide an example of a depiction of the scaffold speech and execution from a contemporary British pamphlet (see figure 1). We discuss the audiences of these public spectacles and contemplate the responses to both Old and New World executions. I review Price’s and Foucault’s understandings of public punishments and ask students how they interpret Oroonoko’s death. For instance, do they see his refusal to show pain as an act of defiance against white supremacy? Or is he adopting British martyrdom traditions? I also ask the students if the depiction of Oroonoko is biased because of Aphra Behn’s race, gender, or class. Through this discussion, students question the possible meaning of Oroonoko’s and other enslaved individuals’s behavior under torture in light of its filtration through a European lens.

Performance and race scholar Ayanna Thompson points out that during the seventeenth century, dramatic representations of the torture of African bodies depicted “the racialized body as something accessible, [96] controllable, and penetrable.”[14] Indeed, Thompson notes that playwright Thomas Southerne’s 1695 adaptation of Behn’s novella, Oroonoko: A Tragedy, worked as an early abolitionist piece not only because it positioned Oroonoko’s torture as inhumane and cruel, but also because it “constantly [restaged] the abjection of the racialized victim.”[15] This portrayal of Oroonoko as the abject victim of violence, although highlighting the prince’s heroism and the injustice of his treatment, is always framed through the gaze of the white audience; thus, while Southerne’s play may challenge racism, it also provides white viewers with the power to determine the nature of Oroonoko’s racial makeup, be it essentialized or constructed.[16] Behn, as a white female narrator, similarly positions herself as the controlling subject, for it is through her gaze that we encounter Oroonoko and through her words that we think through his racialized position in Surinam’s society. [97]

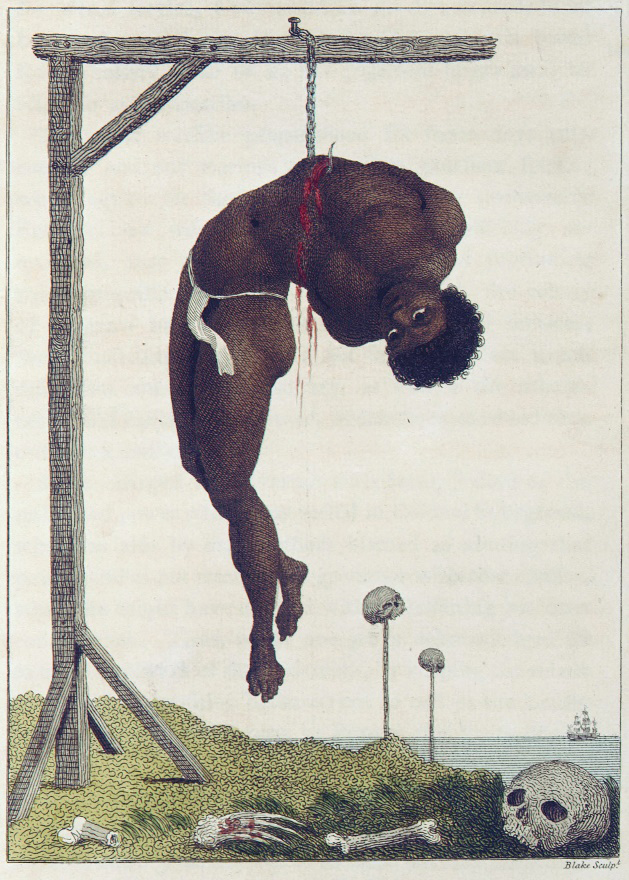

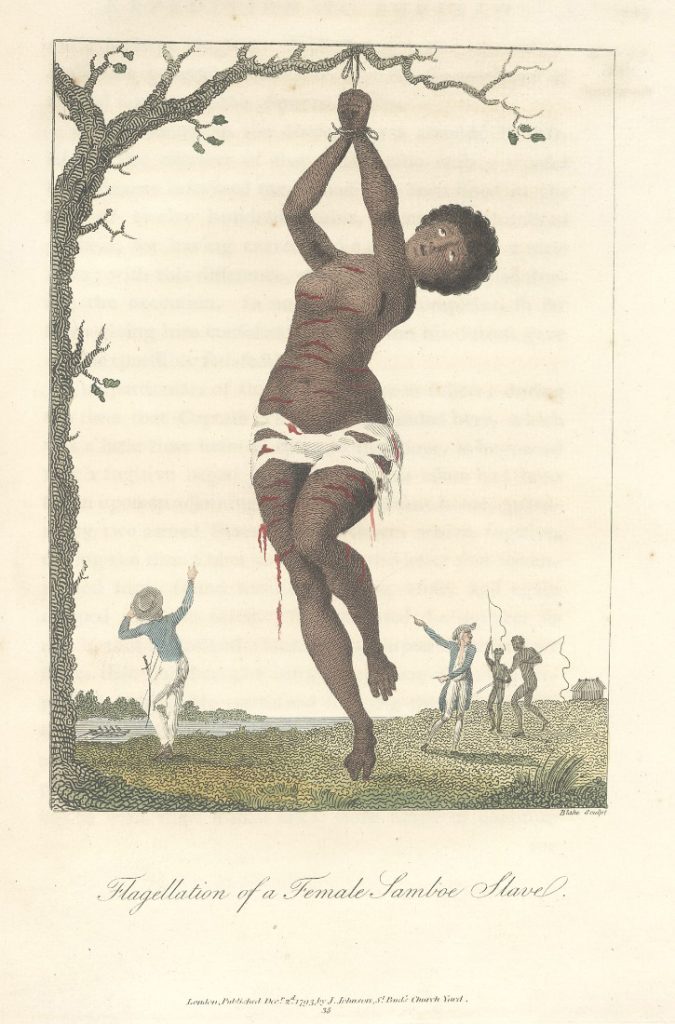

I end the class with a presentation of Blake’s engravings from Stedman’s 1796 Narrative, of a Five Years’ Expedition, against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (see figure 2 and figure 3). Blake’s depictions of African bodies complement the discussion by providing visual representations of torture. Like Behn, Blake looks at the punishment of Africans through a European lens. These images can further the discussion of the racist aspects of punishment in the greater Caribbean world. I ask students to consider how the slaves are represented in Blake’s artwork: Do these engravings, for instance, offer sympathetic portrayals of slaves? How are these Africans responding to torture and punishment? What is Blake’s intent in creating these images?[17] By asking these questions, I want students to consider Blake’s attempt to sympathize with African peoples as well as his eroticization of the black body.[18]

These two conflicting strategies used by Blake to frame the torture of black people, in a similar fashion to Behn’s construction of Oroonoko, invite viewers to both identify with the suffering individual and to objectify and “other” the person experiencing torture. Based on eyewitness accounts of punishments, both images I present to students feature the brutal treatment of Black slaves in the Dutch colony of Surinam. At the center of each image is the body of a Black man or woman hanging from a tree or gallows; both appear to gaze away from the viewer as if focused on their pain and each is in a state of undress. Because he presents them as nearly naked Blake seems to accentuate their innocence by symbolically linking them to nature; additionally, the postures of the Black man and woman appear almost erotic due to the curve of their bodies and the aestheticization of their torture. While blood appears in each image, dripping from the ribs of the man and striping the body of the woman, realistic gore remains absent and bodies are not skeletal, but instead appear [98] strong and hardy, suggesting that the original white viewers could more easily gaze upon and romanticize the figures.[19] [100]

Outcomes: Confronting Racism in Behn’s Text

As stated at the outset of this piece, by comparing Oroonoko’s execution to Blake’s engravings, I hope that students will rethink their assumptions about race relations and slavery in the transatlantic world. Although many historians have claimed that the development of classical racism, or the idea that humans could be divided into different subspecies or “races” and that some of these “races” were superior to others did not fully develop until the late eighteenth century, such arguments need reassessment. Much recent scholarship on historical understandings of race rightly points out that early modern writers privileged whiteness and deliberately constructed language and institutions in support of European dominance.[20] Literary critics such as Ian Smith, for instance, establish the earlier Elizabethan obsession with skin color as a mark of cultural difference, noting that for sixteenth- and seventeenth-century writers and performers “race signifie[d] not an abstract essence but a doing, a verbal performance … a continuous pursuit of subjection.”[21] Likewise, critical race theory expert Kim F. Hall shows that the English language helped to establish racial difference, justify the exploitation of non-white peoples, and enable white individuals — men in particular — to define and formulate [101] their identity by comparing themselves to racial “others.”[22] More recently, literary scholar Miles P. Grier argues that not only language and performance, but also early modern English book printing, enabled the reading of Black bodies as less than white bodies within the developing racial hierarchy. According to Grier, “inkface,” which he defines as the “shared field of blackface performance, tattooing, writing, and printing … helped Britons struggling with memories of their own past as tattooed slaves in ancient Rome by transferring the ink mark of servility to other ethnicities as a property of their character.”[23] Thus, while the connections between slavery and race remained emergent rather than fully formed during the seventeenth century, early modern Europeans used a variety of texts, symbols, performances, and actions to essentialize and denigrate Black Africans, which in turn allowed for the development of racialized slavery.[24]

While Behn expresses sympathy with her tragic prince, she never suggests that slavery is an evil institution. Instead, her focus throughout is on [102] Oroonoko’s social status. His enslavement and his execution are wrong, she seems to insist, because of his position as an elite personage, not because of any fundamental immorality of slavery.[25] Indeed, Oroonoko himself, as a prince, owned slaves prior to his capture following indigenous African practices. As literary scholar Gary Gautier convincingly argues, Behn rendered slavery “as a class relation and not a race relation,” even in its nascent British trans-Atalantic context.[26] Students should be aware, however, that Behn’s text inhabits a liminal space in time, and that slavery in the Atlantic world increasingly became based on blackness during the eighteenth century, and that racism was operative in early modern England.[27] In short, Behn was writing about race even if she believed her work reflected class issues rather than racial differences.

Additionally, I stress that Behn’s novel and its depictions of Oroonoko’s punishments and execution place it firmly within the realm of Caribbean texts, as well as Caribbean methods of racial formation and terror. The colonial Caribbean world was a unique place. As historian Thomas W. Krise notes, the form of slavery practiced in the Caribbean “was radically different from the forms of slavery that existed in the rest of the world for thousands of years; it was large-scale and commercial and involved colonies in which the enslaved vastly outnumbered the free population.”[28] [103] As many scholars have argued, the sugar trade that flourished in the Caribbean during the eighteenth century and owed its success to slave labor provided Great Britain with a significant economic advantage over its competitors. In addition, the sugar trade perpetuated and expanded the slave trade to continue producing sugar cane. Because the Caribbean planters were outnumbered by their slaves, fear was an instrument of control. Therefore, executions like Oroonoko’s became strategic public means of “terrifying and grieving” Afro-Caribbean slaves “with frightful spectacles of a mangled king.”[29] Behn’s details about Oroonoko’s punishment, including his stoic endurance, reflect actual historical events. In addition to the account of Herlein, numerous Caribbean texts note the superhuman fortitude displayed by tortured and executed slaves as well as the horrific tortures used to instill obedience in the enslaved population.[30]

With this history in mind, I return to the execution of Oroonoko. I ask students to consider both the way that Oroonoko is executed and the way that he responds to his public torture and death — and how both are racialized. For instance, students should notice that while most British executions in the late seventeenth century involved hanging (except for severe cases of treason), the tortures devised for African slaves were often extremely brutal, harkening back to medieval and early modern punishments no longer used in Great Britain. The account of John Marketman’s execution helps students understand a typical contemporary hanging. Unlike Oroonoko, who is forcibly tied to the post where he will be executed, Marketman is led to the gallows by his weeping mother. And while [104] Oroonoko is given a tobacco pipe to smoke during his demise, Marketman is met by a minister, who provides comforting words of forgiveness and hope for eternal life. As an African man (and as Behn notes, a non-Christian), Oroonoko is deemed unworthy of the comforts given Marketman and is denied an opportunity to provide a final statement.[31]

Marketman’s death is presumably over relatively quickly. Oroonoko’s execution, on the other hand, is cruelly prolonged rather than mercifully swift. As the passage I quoted above conveys, he is slowly killed by the removal of his body parts one after another.[32] Importantly, the first items removed are his genitals, which Leslie Richardson interprets as the white planters’ attempt “to efface his manhood and his humanity” and “an early example of the ideological impulse to feminize nonwhite men in relation to European men.”[33] Oroonoko’s execution, therefore, is meant to function [105] as a fearful and dehumanizing spectacle. By losing the part of himself that denotes his manhood, Oroonoko loses a part of his identity. After the removal of his genitals, Oroonoko suffers the loss of his ears and then his nose, which further serves to “other” him. Finally, the executioner cuts off his arms. All these maimings serve to disempower Oroonoko and deprive him of the body parts that relate most fully to his identity as a human, and a man. Yet, the prince’s stoic behavior may discredit the white men’s attempt to humiliate and subjugate him. Students should analyze their interpretations of the type of execution in terms of its effectiveness. Does Oroonoko’s behavior during his execution ultimately serve the interests of the planters? Does it uphold Oroonoko’s innate nobility? Or does Oroonoko’s approach to his execution do something else entirely?

Despite his dignity and heroic demeanor, Oroonoko’s execution conduct needs to be analyzed as a possibly racist construction, due perhaps in part to Behn’s subject position as a white female author. I want students to understand that his silence is ambiguous and offers multiple meanings.[34] For instance, literary critic Roy Eriksen points out the similarities between Oroonoko and early modern Protestant and Catholic martyrs, who often met their ends with stoic silence that, while signifying resistance to the theological and political ruling party, upheld traditional Christian beliefs by mimicking Christ’s behavior on the cross.[35] Additionally, numerous scholars have noted the parallels between Oroonoko and the executed English king Charles I, viewing Behn’s novella “as a (straightforward) [106] royalist allegory,” and, seemingly, a reminder of the Stuart king’s attempt to frame himself as a martyr prior to his execution.[36]

Conversely, Oroonoko’s stoicism under torture can be read as an act of defiance. Oroonoko’s refusal to cry out may signify his denial of white planters’ power over his body and mind. As historian Thomas W. Krise explains, stories of slave stoicism “remind us that people were criticizing the imperial enterprise from the beginning and that the Africans who were forced to settle in the New World … had vibrant and ancient cultures that both resisted the spread of imperialism and contributed to the richly mixed culture that developed in the Caribbean.”[37] By remaining silent during his execution, Oroonoko may subtly critique the injustice of his treatment and offer other slaves a model of passive resistance.[38]

In conclusion, by comparing Behn’s depiction of Oroonoko’s torture and death to contemporaneous British executions, students gain a greater understanding of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century racism within the greater Caribbean world and its relationship to metropolitan England. Oroonoko is not an easy read emotionally or intellectually for modern students. Instead, it is a complex text that forces students to visualize the [107] horrific treatment of an enslaved man and confront the historical realities of racial slavery. By placing the moment of Oroonoko’s death in conversation with contemporaneous European execution narratives, I hope to instill in students a greater understanding of how racism impacted not only the lives of Caribbean slaves, but their deaths as well.

Thinking about the brutality enacted on Black bodies in our shared and fraught past in the Anglophone world often brings up connections to the current and continued dehumanization of and violence against Black individuals. Recent events in the United States, from the murder of George Floyd by a police officer to the shooting of Ahmaud Arbery by white supremacists remind us that the perpetration of violence on Black people continues. Beyond their shock at the inhumane treatment of Oroonoko, students recognize a persistent theme throughout western history — white people have consistently othered Black people in an attempt to rationalize their colonist oppression and to justify their continued use of violence against Black people. Perhaps, though, what is most apparent to students engaging deeply with Behn’s novella is the way that Oroonoko’s anguish is rendered as a spectacle for consumption by the implicitly white reader, just as Blake’s engravings offer viewers images of Black suffering. These imaginative spaces, while multifaceted and capable of producing sympathy, also function to induce trauma for Black people and other racialized subalterns. The display of Oroonoko’s pain thereby propagates a narrative of Black illegibility that continues to silence Black voices and render the suffering individual as an unreadable other. In contrast to the relatively more “merciful” executions of white British men and women, which allowed for public repentance and familial involvement, the corporal punishment of Oroonoko is graphic and debasing. As the quote I shared at the beginning of the essay shows, the prince’s execution strips him of his identity and denies him a chance at communal redemption. By reading texts like Oroonoko, my hope is that students will confront the history of antiblack oppression and dehumanization and identify the biases and complacency that still exist within our world. [108]

Suggestions for Further Reading

Behn, Aphra. Oroonoko, or The Royal Slave. in Oroonoko: A Norton Critical Edition, edited by Joanna Lipking. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997.

Krise, Thomas W. “Oroonoko as a Caribbean Text.” In Approaches to Teaching Behn’s Oroonoko, edited by Cynthia Richards and Mary Ann O’Donnell, 92–98. New York: The Modern Language Association of America, 2011.

Little, Arthur L., Jr. “Re-Historicizing Race, White Melancholia, and the Shakespearean Property.” Shakespeare Quarterly 67, no. 1 (Spring 2016): 84–103.

McEvoy, Sean. “The Ethics of Teaching Tragic Narratives.” In Teaching Narrative, edited by Richard Jacobs, 55–69. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Miller, Shannon. “Executing the Body Politic: Inscribing State Violence onto Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko.” In Violence, Politics, and Gender in Early Modern England, edited by Joseph P. Ward, 173–206. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008.

Rivero, Albert J. “Aphra Behn’s ‘Oroonoko’ and the ‘Blank Spaces’ of Colonial Fictions.” Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900 39, no. 3, Restoration and Eighteenth Century (Summer 1999): 443–62.

- The author would like to thank the editors of this volume, as well as Stephanie Bauman, Rob Bauer, Vanessa Cozza, Tracey Hanshew, Kirk McAuley, and Donna Potts, for their advice and comments in relation to this work. ↵

- For examples of teaching practices focused on racial issues see Robin R. Bates, “Using Oroonoko to Teach the Corrosive Effects of Racism,” English Language Overseas Perspectives and Enquiries 3, no. 1–2 (2006): 157–68 and Derek Hughes, “Oroonoko and Blackness,” in Approaches to Teaching Behn’s Oroonoko, ed. Cynthia Richards and Mary Ann O’Donnell (New York: The Modern Language Association of America, 2011), 57–64. For an approach to teaching Oroonoko as an early travel narrative, see Margarete Rubik, “Teaching Oroonoko in the Travel Narrative Course,” in Approaches to Teaching Behn’s Oroonoko, 118–23. Jane Spencer provides a useful discussion of Behn’s gender and her place in the canon in “Behn and the Canon,” in Approaches to Teaching Behn’s Oroonoko, 194–99. ↵

- Aphra Behn, Oroonoko, or The Royal Slave: A True History, in Oroonoko: A Norton Critical Edition, ed. Joanna Lipking (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997), 64. Behn’s inclusion of the pipe, while perhaps unintentional, suggests parallels between the tobacco commonly grown in the New World. For more on the connections between the African prince and American tobacco, see Susan B. Iwanisziw, “Behn’s Novel Investment: ‘Oroonoko’: Kingship, Slavery and Tobacco in English Colonialism,” South Atlantic Review 63, no. 2 (Spring 1998): 75–98. ↵

- For more on this topic, see the following: Sean McEvoy, “The Ethics of Teaching Tragic Narratives,” in Teaching Narrative, ed. Richard Jacobs (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 55–69 and Jack Halberstam, “Trigger Happy: From Content Warning to Censorship,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 42, no. 2 (Winter 2017): 535–42. ↵

- Halberstam, “Trigger Happy,” 541. ↵

- Although technically part of South America, Surinam is usually designated by scholars as part of the greater Caribbean due to the area’s cultural and historical similarities to the islands in the Caribbean Sea. See J. R. McNeill, Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) and Patrick Taylor, ed. Nation Dance: Religion, Identity, and Cultural Difference in the Caribbean (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2001). ↵

- Anonymous, The True Narrative of the Execution of John Marketman, Chrynrgian, of Westham in Essex, for Committing a Horrible & Bloody Murther Upon the Body of his Wife, That Was Big with Child When He Stabbed Her (London: s.m., 1680), 4. For access to this source, visit the University of Michigan’s Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership, which provides scholars with editions of early modern works for research purposes (https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebogroup/). ↵

- For other useful accounts of the execution behavior of seventeenth-century British men and women that showcase repentance, warnings to the crowd, and a final prayer, see the following: Anonymous, News from Islington, or, The Confession and Execution of George Allin, Butcher (London, 1674), 1–6; Anonymous, The True Narrative of the Confession and Execution of Elizabeth Hare … (London, 1683) 1–4; Anonymous, A true and perfect relation of the grand traytors execution …. Together with their severall speeches and confessions (London: Printed for William Gilbertson, 1660), 1; and Anonymous, A True Narrative of the Confession and Execution of Several Notorious Malefactors at Tyburn on Wednesday April the 16th 1684 (London, 1684), 1–4. For more information on the English ritual of execution see J. A. Sharpe, “‘Last Dying Speeches’: Religion, Ideology and Public Execution in Seventeenth-Century England,” Past and Present 107 (May 1985): 144–67 and Katherine Royer, The English Execution Narrative, 1200–1700 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2014). For instructors without access to Early English Books Online, the following sources are open access and readily available to all scholars: English Broadside Ballad Archive (http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/), The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674–1913 (https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/), and Una McIlvenna’s Execution Ballads (https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/execution-ballads/). ↵

- Richard Price, “Violence and Hope in a Space of Death: Paramaribo” Common-Place 3, no. 4 (July 2003), n.p. http://www.common-place-archives.org/vol-03/no-04/paramaribo/. A similar description of a late-eighteenth-century execution of a Koromantyn slave is provided in Bryan Edward’s history of the West Indies. See Edwards, The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies, Vol. 2, London: John Stockdale, 1793, 98. ↵

- While fewer accounts of the punishments of Caribbean slave women exist, John Gabriel Stedman does mention one eighteenth-century female slave at Paramaribo who was given 400 lashes and “bore them without a complaint.” Thus, it is likely that female slaves exhibited similar stoic behaviors when executed. See Stedman, Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, vol. 2, 2nd ed. (London: J. Johnson & Thomas Payne, 1813), 198. ↵

- Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977), 47. ↵

- Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 66. ↵

- Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 33–34. ↵

- Ayanna Thompson, Performing Race and Torture on the Early Modern Stage (New York: Routledge, 2008), 53. ↵

- Thompson, Performing Race, 65. ↵

- Thompson, Performing Race, 51–73. ↵

- This approach is suggested by Mary Ann O’Donnell in her guide to materials in Approaches to Teaching Behn’s Oroonoko, 9. ↵

- For a more in-depth study of Blake’s eroticization of the Surinam slaves, see Marcus Wood, Slavery, Empathy, and Pornography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). ↵

- For further discussion of Blake’s use of eroticized Black bodies in his work, see Mario Klarer, “Humanitarian Pornography: John Gabriel Stedman’s Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolting Negroes of Surinam (1796),” New Literary History 36, no. 4 (Autumn 2005): 559–87 and Debbie Lee, Slavery and the Romantic Imagination (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 99–105. See also Anne K. Mellor’s contention that rather than highlighting the tortures endured by Black Africans, Blake actually “erased the violence against the black body” in his engravings for Stedman’s narrative by omitting the punishing overseers, limiting the blood loss, and leaving out details from the textual account like vultures feeding on the male victim’s corpse. See Mellor, “Blake, Gender and Imperial Ideology: A Response,” in Blake, Politics, and History, ed. Jackie DiSalvo, G. A. Rosso, and Christopher Z. Hobson (New York: Garland, 1998), 351–52. ↵

- Earlier accounts of African peoples, for instance, present a view of Black people as sexually promiscuous and animalistic. Leo Africanus’ A Geographical Historie of Africa, written during the sixteenth century and first translated into English in 1600, offered the following description of Africans: “The Negros likewise leade a beastly kinde of life, being utterly destitute of the use of reason, of dexteritie of wit, and of all artes. Yea they so behave themselves, as if they had continually lived in a forrest among wilde beasts. They have great swarmes of harlots among them; whereupon a man may easily conjecture their manner of living.” See Leo Africanus, A Geographical Historie of Africa, Written in Arabicke and Italian by John Leo a More, borne in Granada, and brought up in Barbarie, trans. John Pory (London: George Bishop, 1600), 42. For a wide range of early modern texts dealing with race, see Race in Early Modern England: A Documentary Companion, ed. Ania Loomba and Jonathan Burton (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). ↵

- Ian Smith, “Barbarian Errors: Performing Race in Early Modern England,” Shakespeare Quarterly 49, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 171. ↵

- Kim F. Hall, Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995). ↵

- Miles P. Grier, “Inkface: The Slave Stigma in England’s Early Imperial Imagination,” in Scripturalizing the Human: The Written as the Political, edited by Vincent L. Wimbush (New York: Routledge, 2015), 195. ↵

- Important scholarship on race in the early modern period has and continues to improve our understanding of blackness and race relations in this era. In addition to the texts mentioned above, see the following: Ania Loomba, Gender, Race, Renaissance Drama (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1989); Joyce Green MacDonald, Women and Race in Early Modern Texts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002); Sujata Iyengar, Shades of Difference : Mythologies of Skin Color in Early Modern England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005); Jyotsna G. Singh, ed., A Companion to the Global Renaissance: English Literature and Culture in the Era of Expansion (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009); Elizabeth Spiller, Reading and the History of Race in the Renaissance (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Arthur L. Little Jr., “Re-Historicizing Race, White Melancholia, and the Shakespearean Property,” Shakespeare Quarterly 67, no. 1 (Spring 2016): 84–103; Matthieu Chapman, Anti-Black Racism in Early Modern English Drama: The Other “Other” (New York: Routledge, 2017); and Cassander L. Smith, Nicholas R. Jones, and Miles P. Grier, ed. Early Modern Black Diaspora Studies: A Critical Anthology (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). ↵

- Gary Gautier, in his comparison of Behn’s novella, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and Olaudah Equiano’s biography, posits a similar argument, noting that “the commercial order, in assigning Oroonoko to the vertical rank of slave without regard to blood quality, fails to assign his identity in a culturally intelligible way.” See Gautier, “Slavery and the Fashioning of Race in Oroonoko, Robinson Crusoe, and Equiano’s Life,” The Eighteenth Century: Theory and Interpretation 42, no. 2 (2001): 161–79, at 165. ↵

- See Gautier, “Slavery and the Fashioning of Race,” 163. ↵

- For more on the development of Atlantic slavery and its connection to race, see Edward B. Rugemer, “The Development of Mastery and Race in the Comprehensive Slave Codes of the Greater Caribbean during the Seventeenth Century,” The William and Mary Quarterly 70, no. 3 (July 2013): 429–58. ↵

- Thomas W. Krise, “Oroonoko as a Caribbean Text,” in Approaches to Teaching Behn’s Oroonoko, ed. Cynthia Richards and Mary Ann O’Donnell (New York: The Modern Language Association of America, 2011), 93. For more on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century slavery in the Caribbean, see Charles C. Mann, 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (New York: Vintage Books, 2012), 93–95, 99–116. ↵

- Behn, Oroonoko, 65. ↵

- In his 1667 study of Surinam, for example, George Warren notes that African slaves “manifest their fortitude, or rather obstinacy in suffering the most exquisite tortures [that] can be inflicted upon them, for a terror and example to others without shrinking.” See George Warren, An Impartial Description of Surinam upon the Continent of Guiana in America: With a History of Several Strange Beasts, Birds, Fishes, Serpents, Insects, and the Customs of that Colony, etc. (London, 1667), 19. For a particularly disturbing account of slave punishments, see Trevor Burnard, Majesty, Tyranny, and Desire: Thomas Thistlewood and His Slaves in the Anglo-Jamaican World (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004). ↵

- For executed slaves in British colonial outposts few if any records of ritual speeches exist, leading historian Diana Paton to surmise that because the slaves were considered outside of civilized society by their European overseers and unaccustomed to accepted European execution rituals they “would have been unlikely to produce the ‘appropriate’ penitent speech of the condemned sinner.” See Paton, “Punishment, Crime, and the Bodies of Slaves in Eighteenth-Century Jamaica,” Journal of Social History 34, no. 4 (Summer 2001): 923–954, here 943–944. It should also be noted that Oroonoko’s status as a religious other by virtue of both his ethnicity and choice means that his approach to death and the afterlife remain unarticulated perhaps because Behn lacks the language to accurately represent the prince’s beliefs. Additionally, the Christianization of racial others during this time period was a matter of debate. As Lauren Shook points out, the expansion of the British Atlantic coincided with the classification of “those that looked, acted, and worshipped differently than them, couching those differences in religious rhetoric”; additionally, such rhetoric implied that African people, due to their descent from Noah’s son, Ham, were incapable of true salvation. See Shook, “[L]ooking at me my body across distances’: Toni Morrison’s A Mercy and Seventeenth-Century European Religious Concepts of Race,” in Early Modern Black Diaspora Studies: A Critical Anthology, edited by Cassander L. Smith, Nicholas R. Jones, and Miles P. Grier (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 159, 160 and David M. Whitford, The Curse of Ham in the Early Modern Era: The Bible and the Justifications for Slavery (Burlington: Ashgate, 2009). ↵

- Behn, Oroonoko, 64–65. ↵

- Leslie Richardson, “Teaching Oroonoko at a Historically Black University,” in Approaches to Teaching Behn’s Oroonoko, 128. ↵

- As Cheryl Glenn argues in her study of silence, choosing not to speak is often a strategic choice that can communicate empowerment and resistance just as often as it disempowers. See Glenn, Unspoken: The Rhetoric of Silence (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004). ↵

- Roy Eriksen, “Between Saints’ Lives and Novella: The Drama of Oroonoko, or the Royal Slave (1688)” in Aphra Behn and Her Female Successors, ed. by Margarete Rubik, (Münster: LIT, 2001), 123. For more on sixteenth- and seventh-century martyrdom, see Sarah Covington, The Trail of Martyrdom: Persecution and Resistance in Sixteenth-Century England (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2003); Andrea McKenzie, Tyburn’s Martyrs: Execution in England, 1675–1775 (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007); and John R. Knott, Discourses of Martyrdom in English Literature, 1563–1694 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). ↵

- Megan Griffin, “Dismembering the Sovereign in Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko,” English Literary History 86, no. 1 (Spring 2019): 107–33, at 108. ↵

- Krise, “Oroonoko as a Caribbean Text,” 96. Reports of similar execution behaviors by African slaves followed the 1675 rebellion in Barbados. Jenny Shaw relates that before his burning, the West African slave Tony persuaded his fellow victims to “not speak one word more.” According to Shaw, this rhetoric of silence “became a source of strength for Tony, and for others who took heart from his show of defiance” and in the West African belief that death would return them to their homelands. See Shaw, Everyday Life in the Early English Caribbean: Irish, Africans, and the Construction of Difference (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2013), 135–37. ↵

- Natalie Zemon Davis points out that West African slaves in Surinam would have been familiar with ordeals meant to establish the guilt or innocence of an individual based on their physical reactions to pain. Therefore, Oroonoko’s heroism may reflect his training to endure pain and his understanding of Gold Coast rituals that stressed silence and relied on the body’s manifestation of signs. See Natalie Zemon Davis, “Judges, Master, Diviners: Slaves’ Experience of Criminal Justice in Colonial Suriname,” Law and History Review 29, no. 4, Law, Slavery, and Justice: A Special Issue (November 2011): 925–984, at 963–64. ↵