American Moor: Othello, Race, and the Conversations Here and Now

Marjorie Rubright and Amy Rodgers

[print edition page number: 469]

In their 2019 MLA essay in Profession, “BlacKKKShakespearean: A Call to Action for Medieval and Early Modern Studies,” Kimberly Anne Coles, Kim F. Hall, and Ayanna Thompson provide five axioms for expanding our reach in what we teach and why, to whom we teach, and how we diversify the pipeline of students entering early modern studies.[1] Starting with the acknowledgement that “our fields of study are not politically neutral,” Coles, Hall, and Thompson propose that the work of attracting a multiplicity of students to pre- and early modern fields will require that we: Start Early; Provide Mentors; Create Inclusive Events; Support Professional Training Across Institutions; and Cite Scholars of Color. While this crystalizing call to action was published after the American Moor Five College residency that we discuss in this chapter, this artistic and scholarly project pursued similar goals, and, we hope, offers an interdisciplinary, performance-forward model for meeting them.

The brainchild of stage and television actor Keith Hamilton Cobb, American Moor explores the legacy of William Shakespeare’s Othello via the perspective of a Black American actor auditioning for the eponymous lead role.[2] At the request of the “director” character (typed as a young, white man fresh out of an MFA program), Cobb performs only one monologue from the play — Othello’s Act I address to the Venetian senate, the governing body of white, European aristocrats who call Othello to appear before them to answer, simultaneously, their call to lead the Venetian fleet against the advancing Ottoman force and the charge that he has [470] “abducted,” and married, one of their most prominent citizen’s only daughter. From here, American Moor diverges sharply from Othello in content while following some similar, and transhistorically relevant, thematic avenues. If Cobb’s narrative takes us on journey of the African American actor’s relationship to one of the two Shakespeare roles that he is “destined” to play (the other being Aaron the Moor from Titus Andronicus), both plays explore the profound consequences of what W.E.B. Du Bois called double-consciousness: the reality of living as a Black subject in a hegemonically white world. As Du Bois claims, “After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second sight in this American world — a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”[3] That the twenty-first century African American actor’s journey should intersect with a fictional seventeenth-century Black, Venetian general’s seemed sufficiently extraordinary (and yet painfully unsurprising) to create an interdisciplinary, multi-campus event dedicated to exploring the histories of (and cross-currents between) these two stories separated by more than three centuries and yet still traveling hand-in-hand through our own contemporary racial moment.

Playwright Keith Hamilton Cobb is probably most well-known for his extensive television work on ABC’s daytime drama All My Children and the Syfy original series Andromeda; however, he is also a classically trained actor with an extensive theater resume.[4] According to Cobb, American Moor “was born out of a perpetual state of disquiet with the experience of African American manhood. Othello, the role, and the play, and the real [471] estate that both have occupied in my life are intrinsic to that experience.”[5] In her introduction to the 2020 publication of American Moor, Kim F. Hall, one of the leading figures in premodern critical race studies, describes the play as following: “a veteran Black actor auditioning to play Shakespeare’s Othello for an unseasoned, white director. It is the story of how his blackness and his love of Shakespeare collide with the largely white Shakespeare industry — the teachers, acting coaches, agents, directors (and scholars?) — who subtly maintain ownership over Shakespeare while at the same time insisting that Shakespeare is a universal public good.”[6]

The American Moor residency began on Friday, November 2, 2018, and ran for just under three weeks with events transpiring across three campuses. Western Massachusetts is home to the Five College Consortium, consisting of four liberal arts colleges (Amherst, Hampshire, Mount Holyoke, and Smith) and the flagship state university of Massachusetts (University of Massachusetts – Amherst).[7] Once the four-show, sold-out run ended at Mount Holyoke, Cobb spent a further week at the University of Massachusetts – Amherst, and a day at Amherst College. Structurally, the residency was organized so that most of the Mount Holyoke events took place prior to the performances and the University of Massachusetts – Amherst and Amherst College events took place in the days immediately [472] following the run. The arc of events followed a sine curve, in which the performances and conference (discussed below) formed the peak activity, and the individual campus events formed the slopes.

The American Moor residency endeavored to create an affective and intellectual network — a community — that came together around a series of events dedicated to the topic of Shakespeare, race, and America. Of equal significance were the key questions that this community raised and returned to over the residency’s sixteen-day span, and that the conversations inspired by these questions diversified not only who was included but who shaped them. It invested students as creators and leaders of the conversation from the start, empowering them to become advocates, teachers, and community ambassadors. At this essay’s conclusion, we return to the call to action with which the chapter opens to propose a sixth axiom that proved crucial to our collaborative pursuits in 2018: foster local community that extends beyond the university.

The residency began with a simple impulse: Amy Rodgers, a faculty member at Mount Holyoke College, saw the show at Boston’s O.W.I theater, found it deeply moving, and wanted her students to see it as well.[8] In particular, she felt that the play contained a unique ability to vocalize the affective, intellectual, and discursive aphasia around American race relations. Like many college campuses, Mount Holyoke consistently seeks new methods for engaging community discourse around diversity, equity, and inclusion; however, the performing arts had been surprisingly absent from these college-wide conversations.

Initially, Rodgers aimed to bring American Moor to the Mount Holyoke campus as a contribution to the institution’s evolving diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives; in conversing with Marjorie Rubright, a professor of English at the University of Massachusetts – Amherst, about bringing the play to the Connecticut River Valley area, a more ambitious [473] and wide-ranging set of programming and conversational opportunities emerged. Our shared goal was to generate a robust series of integrated, creative, public-facing, and scholarly programming across multiple campuses that put race squarely at the discussion’s center. We oriented our energies around two open questions: how do Othello’s legacies speak to urgent questions about race in America today; and how might the performing arts serve as a centerpiece for both pedagogical innovation and enriched scholarly and creative cross-pollination between our campus communities, particularly around matters of race and racism?

After ten months of planning, programming, and significant fundraising efforts at both Mount Holyoke and the University of Massachusetts – Amherst (UMass), the American Moor residency came to fruition. Our aim here in chronicling and reflecting on this endeavor is to articulate how it succeeded in meeting a number of college, university, consortium, and community goals, as well as the ways in which we gained greater insight into how to engage diverse students, faculty, and the larger community in wide-ranging, multi-campus, events-based residencies, particularly those that feature a performance event as the centerpiece. The 2018 American Moor residency was a robust — and scalable — residency. In outlining its contours, we offer one model from which readers might pluck selectively or build upon in an effort to design future cross-institutional collaborations that center conversations about race.

The Embodied Residency: Voices, Questions, and Conversations

“What do we do when they laugh, but I want to cry?” With a voice tremulous with both courage and apprehension, an African American English major ventured his question from the back of the theater, breaking the silence that hung among us following Keith Hamilton Cobb’s performance of American Moor. In the still-darkened Mount Holyoke College Rooke theater, filled with undergraduate students from various humanities departments across multiple campuses, this was but the first of many powerful questions that arose in the weeks of the Five College residency. Responding intuitively, intellectually, and emotionally, Cobb extended both his gaze and arms out into the audience in response, as if [474] drawing this student into the orbit of his confidence: “I hear the silences, too, you know?” Elaborating, he explained that sadness, pain, and rage registers in an audience’s silence — inside that particular student’s feeling of wanting to cry when others laugh — and that this makes its way to the actor’s ears, too. “Not everyone is laughing, and I hear that.” The larger question — “What do we do”? — was met with Cobb’s explicit, intimate, and immediate answer, “we cry — you and I cry — we should!” and with a more implicit answer that forecasted conversations to come in the days ahead: “we must listen to one another — and we’re not really doing that yet, are we?” Cobb thus began a conversation that did more than transform how students in one corner of New England think about race in America today. Through his performances and conversations with students across multiple campuses, Cobb transformed the nature of the questions that students feel they can ask, and who feels welcome to ask them.

The audience on that particular afternoon had spent the weeks running up to the performance studying the racial and racist logics circulating in Shakespeare’s Othello with Amy Rodgers (a white, cisgendered woman) and Marjorie Rubright (a white, queer, feminist and director of the Kinney Center for Interdisciplinary Renaissance Studies at UMass Amherst). Together, we asked our students to embark on various ventures in understanding early modern systems of power and epistemologies of race and to consider their on-going legacies today: they’d written analyses of singular words from Shakespeare’s play (Barbary, Moor, tupping, etc.) for how language gestates and produces race-thinking in the period; they explored the interconnections between ethnic and racial representations of human kinds on the stage and representations of human difference on the pages of early modern world maps;[9] they anatomized entire speeches for how Othello seems to master the threatening discourses of Othering in the play; they wrote reviews of various film adaptations of Othello with [475] an eye toward the implicit biases of casting, cutting, and the direction of mise-en-scene; they wrote their own twenty-first-century versions of a single scene of Othello, illuminating or deliberately rejecting the legacies of early modern race-thinking alive in Shakespeare’s play; they read and discussed Kim F. Hall’s introductory chapters on race and cultural geography in her Bedford Othello in preparation for discussions they would have with her upon her visit to campus.[10] Students also wrote labels for a Mount Holyoke Art Museum exhibit featuring Curlee Raven Holton’s etchings of Othello completed during a Venice residency in 2012. They crafted teaching plans for the play and visited various first-year seminars that were working with Shakespeare’s Othello. Students also met regularly at the Kinney Center for Interdisciplinary Renaissance Studies, where, using the rare book collection on site, they helped to curate an exhibit of books: “Othello in Context, Then and Now.” Finally, mentored work-study and internships offered Mount Holyoke and UMass Amherst students opportunities to work together over the course of the residency as “American Moor Ambassadors.” Designing outreach across the campuses, developing pop-up events, and organizing with other student groups on our campuses, the Ambassadors put students’ investments and questions at the forefront of the residency. Simply put, our students were thick into Othello before American Moor came to town.

Chronicling the Residency

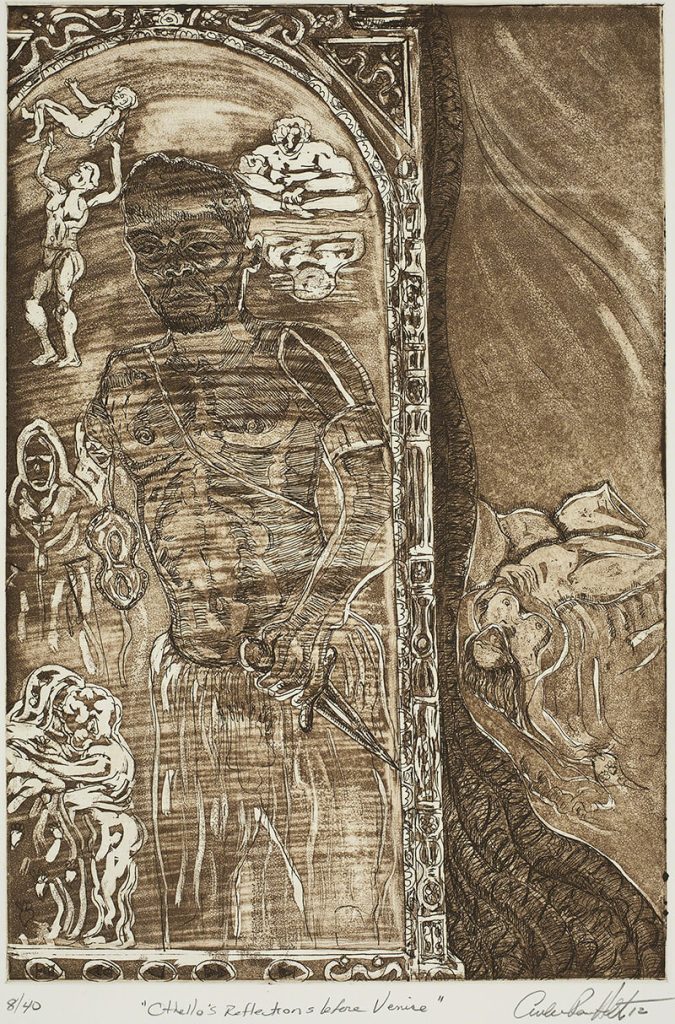

The residency opened with a gallery exhibition entitled “Othello Reimagined in Sepia,” displayed in the Anne Greer and Frederic B. Garonzik Family Gallery, Mount Holyoke College. The brainchild of Rodgers and Ellen Alvord, Associate Director of Education and Weatherbie Curator of Academic Programs at Mount Holyoke, the Museum event brought together Cobb’s performance with an exhibit featuring the founding director of Lafayette College’s Experimental Printmaking Institute, Curlee Raven Holton’s series of prints entitled “Othello Reimagined in Sepia”. [477]

Created during a 2012 residency at the Venice Printmaking Studio, Holton’s images chart new terrain into Othello’s inner life — his affective past and psychic present — as a means of offering an alternative (or perhaps supplemental) narrative to Shakespeare’s play. Professor, painter, and master print maker Curlee Raven Holton engaged in public conversation with Cobb on “African American Perspectives on Othello,” with Rodgers as facilitator.

During their time at Mount Holyoke, the American Moor team (Cobb, director Kim Weild, actor Josh Tyson, and stage manager Caleb Spivey) were in tech for six days preceding the play’s four-day public run; Cobb and Weild also visited twelve Mount Holyoke classes and attended two community events (the Holton event at the art museum and another for the Students of Color Committee on the topic of “Engaging Race through the Arts”). In addition, Caleb Spivey, American Moor’s stage manager, ran a workshop for theater students interested in stage management, and Cobb, Weild, and Spivey were available for less-formal student meetings and conversations.

The scholarly programming was inaugurated earlier in the fall with the Normand Berlin Lecture, delivered by Professor Mazen Naous (Dept. of English, UMass Amherst) who spoke on Diana Abu-Jaber’s Arab-American novel Crescent, thereby launching a Five College-wide discussion of Othello’s global afterlives.[11] These conversations flowed into the curriculum across the campuses where Shakespeare’s Othello was a shared text. During the American Moor residency, Kim F. Hall (Lucyle Hook Professor of English and Professor of Africana Studies, Barnard College, Columbia University) delivered a historically wide-ranging keynote at the UMass Amherst Fine Arts Center, “‘Othello Was My Grandfather’: Shakespeare and Race in the African Diaspora.” A preeminent scholar of Black feminist studies, critical race theory, slavery studies, and early modern literature and culture, Hall is also the editor of the influential Bedford edition of Othello, which Keith Hamilton Cobb holds in his hands throughout American Moor and our students studied from throughout the semester. Her [478] talk explored connections between Shakespeare and freedom dreams in the African Diaspora, outlining a tension between the ways that Shakespeare and blackness have been valued in the 400 years since Shakespeare’s birth. It opened onto the ways that Black writers and actors in the early twentieth century used Shakespeare when grappling with constructions of blackness and race in the United States.

Our conversations bridged research and the creative arts by way of an afternoon conference, loosely based on the concept of the Ovation Network’s series “Inside the Actors Studio,” facilitated by the Trinidad and Tobago-born actor, movement artist, teacher, and director, Jude Sandy. Currently a Resident Artist at the Trinity Repertory Company, Sandy has performed numerous roles on, off-, and off-off-Broadway, including two years in the Tony Award-winning War Horse at Lincoln Center Theater. Together, Weild, Cobb, Hall, and Sandy engaged our academic and public communities in urgent conversations about Shakespeare, race, and America [479]today, conversations in which the humanities’ role in excavating new avenues of discourse and forms of political action featured prominently, particularly around the potency of narrative and performance to communicate across difference.

Following this event, UMass Amherst students returned to the classroom with tremendous enthusiasm for the kinds of questions these artists and academics were asking. In her recent essay, “Why Black Lives Matter in the Humanities,” Felice Blake, a professor of English at the University of Santa Barbara, admonishes: “It isn’t enough to include texts by historically aggrieved populations in the curriculum and classroom without producing new approaches to reading” (309).[12] On its face, Cobb’s dramatized audition for the role of Othello is just that: a heart-wrenching appeal for new approaches to reading which can only be activated by deepened capacities for listening to the presence of the past in our present moment. Hall’s talk engendered significant interest from students of color for how, throughout, she claimed not only to relate to stories of the African Diaspora but be related to that history. She offered our students a new approach to reading. “It was personal while also being scholarly,” one student remarked. “I think more often we’re taught that we’re supposed to stand outside history, looking back at it like an object in a museum, untouchable” another offered. When asked if they felt there were similarities between Hall’s scholarly keynote and the conversation that followed between Hall and the actors and director, a white theater-studies student remarked that “history felt present.” Her Black friend nodded, then reshaped the formulation: “I felt present in that history of black oppression and resistance. I mean, I could feel it . . . in me and in the room.” “I think that’s what American Moor does in a different way,” another student added. “Isn’t Keith’s audition all about who does and doesn’t feel history as present ‘in the room’?” [480]

Following his residency at Mount Holyoke, Cobb spent a week in residence at the Kinney Center for Interdisciplinary Renaissance Studies at the University of Massachusetts – Amherst, holding workshops and roundtables with students from the departments of English, history, theater, Afro-American studies, and women, gender, and sexuality studies. He also participated in classroom conversations with students. During Cobb’s visit to Rubright’s introductory Shakespeare course (a large lecture course of sixty students), as well as to a more intimate masters-level theater seminar, students asked the author/actor questions ranging from his “decision to use the N-word in the play and how we should think about that,” to whether “it’s different to say that word aloud to a NYC audience than in Western Mass,” which is predominately white. They also ventured questions more personal and biographical: “when did you know you were a writer and an actor and did your family support those choices?” At the conclusion of Cobb’s week-long residency, the Shakespeare students were invited to write a private letter to Cobb reflecting on their experience of American Moor, their conversations with him over his week in residence, and/or on the feelings his residency sparked in them. This epistolary extension of the conversation was private, not to be shared with Rubright or other students. In this way, students continued the conversation off stage, and many reported that writing their letter was “harder than anything” they’d written before. As one student elaborated in a class review, “Cobb was so honest and open with us, I felt I needed to find the words to be as honest” in return.

At Mount Holyoke, Cobb visited Rodgers’ “Activist Shakespeare” class the Monday following the conclusion of American Moor’s run. Students and Cobb together debriefed on the experience of being in the audience (students) and performing the play (Cobb) in Western Massachusetts (and in front of what was a predominantly white audience). As one student of color said to Cobb, “So often I feel like no one sees me here. How do you deal with that, especially since you are putting yourself and your story out there for everyone to see?” Cobb responded with understanding and empathy: “Even if people don’t see exactly what I want them to see, they are seeing me and listening to what I have to say. And they see you. I see you!” This moment of genuine vulnerability was deeply felt by the class community as a whole (many were in tears), and marks precisely the coordinates [481] that demarcate a place where actual change, at the level of heart and head, can occur.[13]

Reflections on the Residency

Despite the consortium structure of the Five Colleges, engaging community across different campuses presents numerous challenges even when institutions co-sponsor high-profile speakers and artists.[14] Event saturation permeates individual campuses, a fact that compounds across the consortium. The American Moor residency occurred in the final third of the semester, when demands on students and faculty are at their height. Even so, the residency managed to gain considerable interest and momentum, evinced by the four sold-out shows, the packed house at UMass’s American Moor Actors Studio and Keynote events, and the fact that Mount Holyoke’s president, dean of faculty (provost), vice-president of diversity, equity, and inclusion, and vice-president of student life all attended the performances — an unprecedented turnout for Mount Holyoke’s officers at a performance-based event, even one at their own campus. [482]

Student response to the residency was highly positive. During their exit interviews, a number of theater majors stated that American Moor provided an experiential zenith in their college experience. One student, from Rodgers’ Activist Shakespeare course, stated “Getting to work with Keith Hamilton Cobb on his Othello adaptation was one of the highlights of my time at Mount Holyoke. During the class he visited, students laughed, cried, and had the most open conversation about race that I’ve had during my three and a half years here.” Elizabeth Young, Carl and Elsie A. Small Professor of English at Mount Holyoke, shared that “[t]he visit by Keith Hamilton Cobb was an excellent experience for students in my course English 199, Introduction to the Study of Literature. It was one of several extraordinary activities for these students related to Shakespeare’s Othello, which also included attending Mr. Cobb’s play American Moor; visiting the exhibition at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum of ‘Othello Reimaged in Sepia,’ by artist Curlee Raven Holton; and attending the conversation between Mr. Holton and Mr. Cobb at the Museum. Discussions about race in the play, and about Black responses to it, that might otherwise have been abstract or speculative were concrete, vivid, and dynamic, ranging across two media (theater and visual art) and emerging from in-person conversation with an actor/playwright.” Indeed, one of the residency’s more successful tactics was its consistent and multidisciplinary imbrication of different artistic and scholarly approaches to Othello and its many artistic and cultural legacies. So too, involving students from the start in the planning and organization of the residency — and doing so with a group of cross-campus Ambassadors who had time to work together, face-to-face, and develop trust with one another — was essential to the groundwork upon which the residency was built.

Students took increasing risks in raising questions — of each other and of American Moor — over the course of the residency. The multi-week timescale of the residency, as well as its traffic through different campus cultures, allowed students time to digest the thoughts of others. Faculty across the disciplines integrated Cobb into their courses: faculty from English, history, Latinx studies, theater, and Africana studies invited Cobb to speak with their students on race, identity, performance, masculinity, and Shakespeare. Students at UMass reported appreciating face-to-face engagements with the performance artist, whom they had opportunities [483] to interview in classroom visits and roundtable events over the course of the week of residency. In particular, students found the combination of interacting with the author/actor both at the intimate level of small class discussion and the public level of the show’s performance and post-show discussions particularly fruitful. Students who initially reported being concerned about “call out culture” — about whether they might ask questions about race in the past and present “without offending” or seeming “not woke,” and others who doubted whether they could tell their own stories about encounters with white supremacy “without getting too emotional” — began to practice, in the more intimate contexts, genuinely searching lines of inquiry that were not stifled by what Black feminist Loretta Ross characterizes as “cancel culture, where people attempt to expunge anyone with whom they do not perfectly agree, rather than remain focused on those who profit from discrimination and injustice.”[15] Cobb’s own style of Q&A in the after show talk backs helped to model the kind of listening these conversations require. Cobb’s interlocutory style encouraged students to raise challenging questions about American Moor itself, which gender-studies students indeed did especially in inquiring about the portrait of Desdemona’s agency in the production: “I wanted more of her voice, her perspective — less her father’s and Othello’s,” one student appealed. Moving from the local (their individual experience of and with race on their campuses) to the national (a performance piece that adapts a canonical Western text to speak to the contemporary experience of a Black American actor seeking validation and expressive agency through the Shakespearean canon within American theater) was an essential part of the exercise and reward of these conversations. Ultimately, it was the saturation of a variety of engagements over the course of the residency that fostered the trust necessary for the challenge of the conversations sparked by American Moor. [484]

In terms of the larger Western Massachusetts community (particularly that outside of the elite Five College milieu), we found that three events drew the most interest: foremost, the performances themselves and the Q&As that followed; secondly, the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum event and related pedagogical opportunities; and third, the Actors Studio at the UMass Fine Arts Center and conversations that it ignited. In addition to the performances, which themselves sparked powerful conversations each evening, these two distinct events share in their endeavor to join public-facing artistic production or public-facing artistic conversations with pedagogical and research investments. Crucially, we discovered that when no one in the room was cast as the ‘expert’ on the topic or the ‘master’ of a craft, everyone joined creatively and more openly in conversation.

The Actors Studio was an occasion to set Keith Hamilton Cobb, Kim Weild, and Professor Kim F. Hall into conversation with one another, thus further dissolving divisions between performance, scholarly research, and the real-world questions about systemic racism at the center of our discussions. What worked especially well was the introduction of a talented intermediary who brought questions to the stage that animated actor, director, and scholar alike. Jude Sandy, an award-winning actor and celebrated teacher, is not part of the American Moor team, though he was familiar with the show. His questions emerged from the position of an informed ‘outsider,’ someone who stood just on the edges of the American Moor project. This bifocal perspective — one foot in the acting world, one foot in the teaching world — made a successful formula for conversation. Students jumped into the Q&A period, as did the community, in large part because Sandy positioned himself — as well as the audience — as possessed of many questions, and few certain answers. What began as a conversation between Cobb, Weild, and Hall soon spilled into a Q&A with an entire auditorium. [485]

‘What’s Past Need Not Be Prologue’

American Moor is as exuberantly hopeful as it is deeply critical.

It is a play with uncommon faith in us. As the audience, we are

simultaneously the Director, the Venetian Senate, and ourselves:

we can stop the racism in the theater and in our lives,

if we can make space and time for learning and listening.

We don’t have to passively play the roles as others imagine them.

What’s past need not be prologue. — Kim F. Hall[16]

Where to go from here? Starting with his generous and generative practice of holding a Q&A following every performance of American Moor, Keith Hamilton Cobb offers one proposal for where to go from here: continue the conversation. The challenge of this straightforward proposal is significant in that it presses those of us teaching race in early modern literature, contemporary theater, and performance studies to ask how we generate these conversations and work to expand the community of interlocutors who shape it. This leads us to suggest a possible sixth axiom in support of Coles, Hall, and Thompson’s call to action: foster local community that extends beyond the university. While Coles, Hall, and Thompson’s five axioms suggest this endeavor tacitly, we believe that making it explicit is imperative, particularly for those who might wish to mount such an initiative at their own institution. As a corollary, colleges and universities must do more to encourage, support, and recognize endeavors like the American Moor residency that arise from the social-justice commitments of faculty, particularly pre-tenure and adjunct faculty. As two mid-career tenured faculty, we encountered skepticism from some professional peers about whether the significant time and work entailed in organizing this residency was “at our own professional peril.” Cues like this can have chilling effects, particularly on early career scholars and faculty in temporary appointments. If we are to continue the conversation, it must not exclude the creative energies of already over-burdened junior faculty of color who may be best suited to continue these conversations [486] around racial injustice but may, nonetheless, feel restricted by the narrowly proscriptive path of publication-toward-tenure. Departments, colleges, and universities must rethink and redesign the evaluative systems of promotion review in an effort to convey the value of this kind of work to adjunct and pre-tenure faculty, and thereby endorse and support it.

Among the residency’s successes was its ability to bring students and faculty from the Five Colleges together to act and imagine themselves as a larger, more wide-ranging force for discussion and (ex)change. Intermingled with those students, staff, and faculty were community members — people who live in the three towns that house the Five Colleges (Amherst, Northampton, and South Hadley). South Hadley (the most working-class of the three) also hosted American Moor’s performances, and Rodgers, with the help of several Mount Holyoke students, publicized it widely to the town, in particular, to the middle and high school. And yet, more could have been done in this area. Holyoke, the city that lies directly south of South Hadley, has a predominantly Latino population (52% according to the United States 2019 Census).[17] Springfield, the third-largest city in Massachusetts, is part of the Connecticut River Valley, and has the largest Black population in the area and the second-largest Latino population.[18] By contrast, Hampshire county where the Five College Consortium is situated is 88% White, 4.3% Black or African American, 5.9% Hispanic or Latino, and 5.7% Asian.[19] Admittedly, little outreach was done in these areas, outside of advertising to postsecondary institutions in the two cities and encouraging UMass students who commute from these communities to bring family and friends. Ideally (and, should such a large-scale performance event occur in the future), we would spend more time [487] and resources toward tracing a larger geographical circumference in terms of outreach and thinking through how such outreach and (hopefully) engagement, might help us begin to break down the silos that separate our communities into taxonomies of race, affluence, and ideology. Perhaps, then, the optimism of American Moor would manifest more fully: “what’s past need not be prologue.”

- Kimberly Anne Coles, Kim F. Hall, and Ayanna Thompson, “BlacKKKShakespearean: A Call to Action for Medieval and Early Modern Studies.” Profession (MLA: 2019) https://profession.mla.org/blackkkshakespearean-a-call-to-action-for-medieval-and-early-modern-studies/ ↵

- On American Moor, visit http://keithhamiltoncobb.com/site/american-moor/ ↵

- W.E.B Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folks. Edited by David W. Blight and Robert Gooding-Williams (Boston: Bedford Books, 1997), 38. ↵

- See, http://www.keithhamiltoncobb.com ↵

- Ferri, Josh. Interview with Keith Hamilton Cobb. Five Burning Questions with American Moor Playwright and Star Keith Hamilton Cobb. Broadway Box, August 21, 2019. https://www.broadwaybox.com/daily-scoop/five-burning-questions-with-american-moors-keith-hamilton-cobb/. ↵

- Hall, Kim F., “Introduction,” American Moor: A Play by Keith Hamilton Cobb (New York: Methuen Drama, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020), ix. ↵

- Among the consortium’s many advantages are a shared library system, a Five College course exchange, and a rich intellectual and pedagogical matrix. There are a number of Five College interdisciplinary organizations and seminars, as well as the Kinney Center for Interdisciplinary Renaissance Studies, which fosters and supports programming with faculty and students across the consortium (https://www.umass.edu/renaissance). While collaboration across the institutional entities is widely encouraged, it often proves difficult, as each institution simultaneously exists (and indeed must exist) as a distinct, even unique, higher educational entity. As such, each institution conceptualizes (and to some extent enrolls) a discrete student body, with differing needs, interests, concerns, and hence administrative apparatuses. ↵

- O.W.I (Bureau of Theatre) was part of the Boston Center for the Arts. Named after the Office of War Information, the small, black-box organization programs theater that explicitly engages with issues of racial identity. The company no longer appears among BCA’s theatrical affiliations, and, as O.W.I does not maintain a website; it is difficult to tell whether it still exists in any capacity. ↵

- For a discussion of this assignment, see Rubright, Marjorie, “Charting New Worlds: The Early Modern World Atlas and Electronic Archives.” Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives, edited by Heidi Brayman Hackel and Ian Frederick Moulton (The Modern Language Association of America, 2015), 201–11. ↵

- Shakespeare, William, Othello, The Moor of Venice: Texts and Contexts, edited by Kim F. Hall (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007). ↵

- A fuller version of this talk is published in Naous, Mazen, Poetics of Visibility in the Contemporary Arab American Novel (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2020) ↵

- Blake, Felice, “Why Black Lives Matter in the Humanities.” Seeing Race Again: Countering Colorblindness across the Disciplines, edited by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Luke Charles Harris, Daniel Martinez HoSang, and George Lipsitz (Oakland: University of California Press 2019), 307–26. ↵

- This Five College residency drew audiences from all Five Colleges and the broader New England community and gained local and national media attention. Amy Rodgers’ interview with Mount Holyoke College, “Race, Shakespeare and America” is available online (https://www.mtholyoke.edu/media/race-shakespeare-and-america). An interview with Cobb and Rubright appeared in The Daily Hampshire Gazette (https://www.gazettenet.com/American-Moor-21221674) and another was printed in The Los Angeles Review of Books (https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/all-this-life-made-this-play-an-interview-with-keith-hamilton-cobb/). In her op-ed piece, Morgan Reppert, Op-A Ed Editor for The Massachusetts Daily Collegian, lauded the immersive and hands-on learning experiences that American Moor offered to undergraduate students (https://dailycollegian.com/2018/11/umass-students-should-learn-by-doing/). ↵

- Mount Holyoke College and the Office of the Provost at the University of Massachusetts – Amherst generously partnered to provide full financial support for this programming, whose costs otherwise exceeded the discretionary budgets of single departments, humanities units, and colleges. ↵

- On the toxicity of call-out culture in Western Massachusetts, see Ross, Loretta, “I’m a Black Feminist. I think Call-Out Culture is Toxic.” The New York Times online (August 17, 2019). https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/17/opinion/sunday/cancel-culture-call-out.html ↵

- Kim F. Hall, “Introduction” to American Moor: A Play by Keith Hamilton Cobb (Methuen Drama 2020), xii. ↵

- US Census Bureau. QuickFacts, Holyoke city, Massachusetts, 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/holyokecitymassachusetts. ↵

- US Census Bureau. QuickFacts, The Census Bureau’s 2019 report cites Springfield’s Black population as 20.9% and its Latino population as 44.7%. ↵

- US Census Bureau. QuickFacts, Hampshire county, Massachusetts, 2019 https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/hampshirecountymassachusetts/PST045219. ↵