Introduction:

Adam’s Rib, Eve’s Voice

Michelle M. Dowd and Thomas Festa

[print edition page number: 1]

In recent years, two distinguished women writers from North America have conducted related but distinct thought experiments. Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Lavinia creatively give voice to the marginalized and silenced inner worlds of two women right at the heart of two of Western civilization’s founding literary works, the Odyssey and the Aeneid.[1] In each case, the wife (or destined wife) of the protagonist opens up a new, eloquent perspective on the action of the epic. Both women — and in Atwood’s tale, Penelope’s chamber maids who by modern standards die innocent in the fury of Odysseus’ homecoming — bear witness to the familiar action and retell the classic stories as their own, thereby expressing what had been left unsaid and was perhaps even unthinkable by the ancient authors. These two novels share in common a fresh sense that ancient tales may be reclaimed in our time without inhibition, and that monumental works of antiquity need not be seen as monolithic or univocal. Instead, as Atwood and Le Guin show us, the worlds of archaic Greece and Italy may provide especially charged fictional settings in which contemporary women might revisit questions of history and gender as they bear on identity. By returning to the literary foundations of Western culture in pagan antiquity, they report from the political and domestic fronts with intelligent skepticism, naturally not requiring readers to agree with belief systems that seem from this distance of time so outdated, so obviously constructed and ideological. In rethinking such key myths of origin from Greece and Rome, these modern authors avoid problems related to readers’ and writers’ religious beliefs altogether.

An analogous thought experiment appeared in the writings of women during the early modern period, but just the opposite was true where religion was concerned. Imagining Eve’s voice in early modern England entailed direct [2] engagement with the most contentious issues of identity in political and social life. And yet, for the women who wrote the poems, prophecies, pamphlets, diaries, and romances included in this anthology, the myth of Adam, Eve, and the Fall of mankind from the Book of Genesis proved inescapable, as it was the most formative story of their culture. The Genesis narrative relates how Eve, against God’s explicit prohibition, took fruit from the Tree of Knowledge and ate it, before giving it to her husband Adam to eat. After eating the fruit — the moment of original sin — both realized they were naked and covered themselves. (For the complete biblical narrative, see Appendices 1 and 2.) From this relatively simple account sprang a host of interpretations that affected nearly every aspect of early modern culture, most notably its ideas about gender inequality. In early modern England, Christians from every sect used the Bible as the key to understanding their past, present, and future. It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that biblical history provided the dominant means of interpreting individual, familial, and political identity in early modern society. These stories, and above all, the story of the Fall, shaped everyone’s relationships to each other, but undoubtedly the myth of the Fall distorted perceptions of women and had complex and often negative effects on relations between the genders. To name just one of the most pervasive and influential interpretations of the story from Genesis: propagation of the doctrine of original sin, from Augustine’s early writings through those of Protestant reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin, entwined sexuality, reproduction, and the physical transmission of sin as a consequence of the Fall.[2]

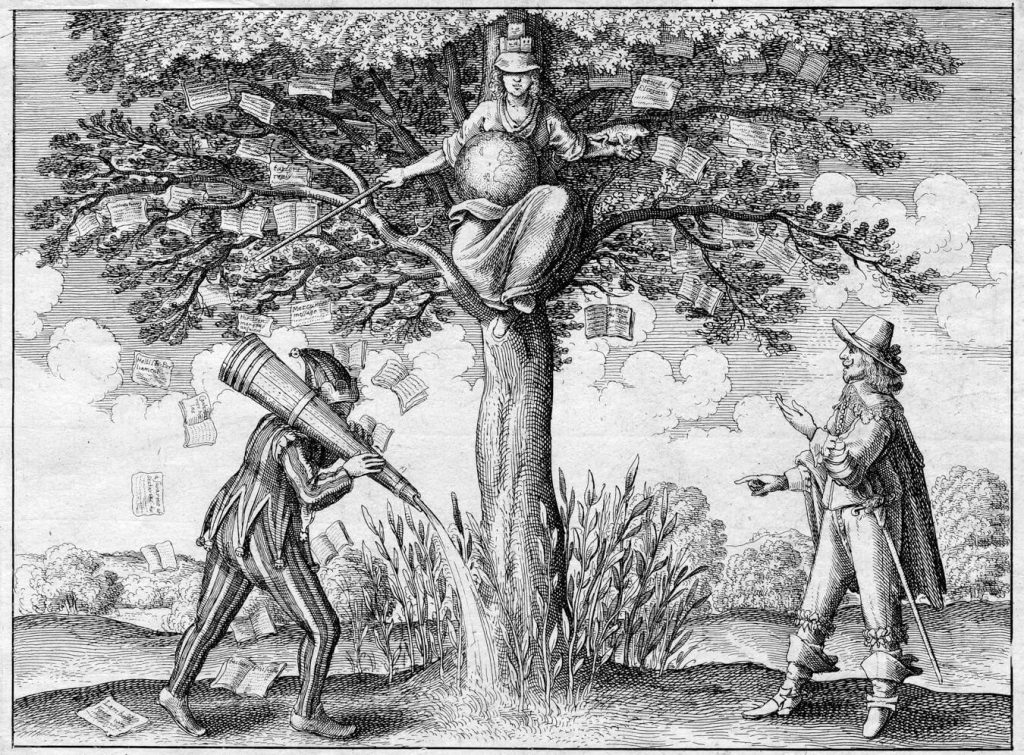

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund, 1919 (19.73.1).

As a result of the revitalized interest in biblical texts and translations that accompanied the Reformation — from its inception in the early decades of the sixteenth century through the increasing circulation of the spectrum of beliefs and practices called by detractors “Puritanism” in Britain in the seventeenth century — more individuals than ever were reading and interpreting the Bible. Undoubtedly, the invention of printing using the technology of movable type, symbolically represented in history by the publication of Johannes Gutenberg’s edition of the Bible in the mid-1450s, made the Bible cheaper to produce and thus more affordable to buy. In England, William Caxton’s introduction of the[3] printing press in 1476 transformed the literary and cultural landscape and, over time, made it easier to disseminate religious ideology to laymen and women. One of the most crucial developments facilitated by the widespread distribution of Bibles and other religious texts following the printing revolution was the formation of communities of belief that included literate, articulate laywomen. As a result, women increasingly turned to the story of the Fall of mankind in order to question and write about their relationship to Christian society and their subordinate place in the social hierarchy. Early modern women were full participants in scriptural debate, sometimes upholding the traditional exegesis of the Fall that blamed Eve for mankind’s demise, at other times producing alternative interpretations of the biblical story.

The texts in this volume engage with the specific discourse of the Fall as a logical, rhetorical, or narrative strategy, in order, furthermore, to address other discourses at the center of early modern society. Since the theme of the Fall of humanity received such extensive attention and did so much varied cultural work, a wide range of concerns beyond the two most obvious ones — theology and politics — emerge from these texts; they comment upon the relationships of women to science and medicine, classical literature, childrearing, education, law, architecture, and even botany. Not merely an introduction to the great variety of women’s lives during the period, the selections in this anthology open a unique window on the complex relationship between those two key words “early” and “modern.” That is, they gesture toward more recognizably “modern” topics such as scientific discovery, political subjectivity, and women’s educational parity while at the same time retaining specifically “early” interests in wetnursing, Neoplatonism, and domestic hierarchy. The texts collected here also provide materials through which to consider such issues as gender and its impact on literary production, religious expression and difference, the profound cultural changes brought about by the English Reformation(s) and Revolution, and the social role played by both print and manuscript culture.

The remainder of this introduction will be devoted to brief explanatory sections on the following topics: the religious and political contexts within which our selections were written; some key conceptual frameworks that arose from those contexts, such as the vast debate over free will and predestination; critical social frameworks for understanding the texts, including the ways in which political and domestic realities intermingled in the period and the conditions surrounding women’s writing; and finally some suggestions about how this anthology might be used, with a few points of clarification about our editorial policies and the materials included in the appendices. [5]

Religious and Political Contexts

It is perhaps hard for twenty-first-century readers to imagine the extent to which religious language informed every aspect of life in early modern England, but we do well to recall that religious conflict still shapes the relationships between societies, and between members of any society.[3] Nonetheless, the place of religion in the daily lives of early modern people was fundamentally different from the roles it plays in people’s lives today. This is not least because, in England during the entire period covered by our anthology, religious practice was intimately connected to the political institutions that shaped society.

Another way of saying this would be to remember that the English church underwent several tectonic shifts during the early modern period, and the earthquakes that resulted were without question powerfully felt by all members of society. The sixteenth century was, on the European Continent, a time of spiritual upheaval and religious war. In England, the official institutions of the English church underwent a related series of transformations, the first of which originated in a struggle directly related to questions of gender and power. King Henry VIII’s split with Rome derived from his desire to father a legitimate male heir to the throne and his conviction that his wife, Catherine of Aragon, was incapable of this. Following Henry VIII’s divorce and the Act of Supremacy in 1534, the monarch of England became the head of the church in England, which changed the relationship between these institutions forever — not least during the brief return to Catholicism under Henry’s first daughter, Queen Mary Tudor.

The return to a Protestant settlement under her sister, Queen Elizabeth I, was not without conflict and ambivalence, even after her excommunication by Pope Pius V in 1570, though in the wake of the intended 1588 invasion by the Spanish Armada, the Protestant cast of most popular literary works became even more enthusiastic and vociferous. One need only think of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus or Book I of Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene to recognize how central the political and doctrinal struggle against Catholicism had become in English society and letters. Although the established church of England, particularly as imagined by theologian and theorist Richard Hooker at the end of the sixteenth century, meticulously hewed to the so-called “middle way,” there was throughout the period considerable contestation over the forms belief might take. If anything, the foreign policy of Elizabeth’s successor, King James I, mirrors this confusion. The lives (and writings) of some famous male poets of the early seventeenth century make this ambiguity of belief legible: both John Donne and Ben Jonson were at various times in their lives Catholic and at others Protestant,[6] to say nothing of the most famous English writer of the period, William Shakespeare, whose religious identity is still hotly disputed by literary historians.

By the 1640s, the fractures within the English community of believers had all but shattered the polity. James’s son, King Charles I, had centralized the authority of the monarchy and failed to call Parliament to session for a dozen years; married a Catholic queen, Henrietta Maria of France; and elevated a bishop with extremely Catholic-leaning ideas about church hierarchy and practice, Archbishop William Laud. In the middle of the seventeenth century, then, the English Civil Wars were fought between the king and the followers of Parliament, who tended to be Puritans, or radical Protestants. Parliamentary forces were victorious; the king was beheaded in 1649; and the church was disestablished in England. The effects of this radical transformation on English society cannot be overestimated.[4] Some of our authors were intimately affected by the Civil Wars. For example, Lucy Hutchinson’s husband John was a colonel in the Parliamentary army who signed King Charles’s death warrant and died in prison following the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy and the return of Charles II to power. Margaret Cavendish followed Queen Henrietta Maria into exile in France during the Interregnum; when she and her husband William returned to England after the Civil Wars, he was unable to secure a court appointment and they were forced to retire to the country. Not all of the authors included in our anthology were as directly influenced by the large-scale, historic changes of the age, but all who lived through this period were affected in countless and complex ways. Persecution and toleration played out in an uneasy dialectic throughout the period, a fact that extends far beyond the Civil Wars and Interregnum in English history.[5]

Our selections begin with a response that rewrites patriarchal historiography in Aemilia Lanyer’s Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum and end with the spirited rejection by Lady Mary Chudleigh’s character “Melissa” of the use of Eve an a negative exemplar by the unnamed “Parson” in her dialogue. Beginning with a bold revision and ending with a dialogue in which a woman intelligently and forcefully reasons against religiously justified oppression, our authors make widely divergent, even contradictory, use of the examples provided by scriptural precedent. This practice and its ideologically variegated results were not of course restricted to women writers. Such use of biblical exegesis to buttress arguments of [7] all kinds served as the most common argumentative strategy among virtually all polemicists throughout the period. Writers made arguments through, about, and against biblical proof-texts, often citing one passage against another and freely deploying the authority of scripture in ways that were pious, learned, creative, or merely convenient. Whole shelves could be filled with books arguing over the social and political implications of a single verse.

One of our hopes for this anthology, then, is that it should dispel the simplistic myth that religion functioned only to disempower women in the pre-modern era, or that the story of Eve’s fall did not have a productive as well as a counterproductive force in English society during the pre-modern period. Ultimately, we hope readers will keep in mind that the modern narrative of the emergence of secular modernity with an accompanying autonomous political subjectivity remains a self-congratulatory and self-serving one. Although social progress for women and men did undoubtedly arise by means of a secularizing Enlightenment, the early modern period, poised Janus-faced as it is between two ages, still articulated its most deeply held convictions and its most intractable truths in the contested language of religion. [8]

The Contest of Ideas in Early Modern Religion

From the moment the Augustinian monk Martin Luther posted his ninety-five theses (called “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences” in the original Latin) on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, on 31 October 1517, the conflict over the institutional authority of the Catholic Church took place on a battlefield of ideas and involved a number of separate skirmishes over the clerical practices these ideas were used to support.[6] Although the nature of the protest against church hierarchy was complex, the movement began with a debate over the use and abuse of priestly authority, particularly the role of the clergy as intermediaries between individual believers and rituals of absolution and contrition.

The most central tenets of the initial movement may be distilled into the slogans that arose from the teachings of Luther and those who followed him: sola gratia (“by grace alone”), sola fide (“by faith alone”), and sola scriptura (“by scripture alone”). Locating authority for his arguments in the Epistles of St. Paul to the Romans and Galatians among others, Luther resisted the Catholic emphasis on human action producing spiritual results — the idea that the deity might be responsive, for example, to the good deeds or “works” of human beings.[7] Emphasizing the Pauline texts, Luther wrote in opposition to the Doctrine of Works, which was itself grounded in another scriptural text, found in the Epistle of James: “For as a body without the spirit is dead, so faith without works is dead also” (2:26 in the King James Version). The early Reformers believed that justification or rectification of an individual could not ensue as a result of good deeds, or the expenditure of cash or effort on behalf of a noble cause. Instead, Luther counterposed the idea that justification, or being made right by God, occurred only through the unmerited visitation of grace. The sole expression of the desire of an individual to receive an infusion of divine grace was, therefore, indirectly through faith, not directly through works. No quid pro quo could be enacted, since the deity’s power so far exceeded the comprehension of the human mind and the deity’s actions and intentions remained hidden. Born already corrupted as a result of original sin, human beings simply had to await God’s grace and sustain a faithful disposition through a rigorous and continual process of self-examination. Only an inconceivably proud and arrogant person, thought Luther, could believe that he or she merited eternal bliss, especially since no one could [9] possibly live up to a comparison with Christ, who bestowed his own ultimate merit on humanity. Moreover, to imagine that human beings could grasp the divine mind or God’s providential intention would be to make God in humanity’s image, a reduction that struck Luther as the worst kind of blasphemy. The sole authority to which human beings could refer for knowledge of God was scripture, the study of which, according to the reformers, ought to occupy a privileged place at the center of every Christian life as the exclusive means of access to divine truth.

Among the many conceptual flashpoints that arose from the early years of Protestantism, the argument over human agency had perhaps the most wide-ranging implications and the longest lasting effects on the nature of religious practice. These arguments, given their classic form in the ferocious debate in print between the Catholic Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus and Luther, involved two irreconcilable positions on the possible meaning of all human actions.[8] At stake was the authority of traditions of Christian thought going back to the earliest writings of the Church, which Luther in effect put on trial and found wanting. Erasmus, defending the traditions and, it must be said, a more rationalist and humanistic compromise, argued for the essential freedom of the human will. Luther, amid a flurry of name-calling and unyielding (even scatological) attack, insisted on the fundamental bondage of the human will. In the end, although Erasmus reasoned carefully and persuasively, it was Luther’s position that held sway for its vehemence and its passion in the growing Protestant communities of northern Europe.

The two positions of Luther and Erasmus, which essentially reproduce the structure of the argument between faith and works as pathways to salvation, attached therefore to the concepts of predestination (Luther’s position) and free will (Erasmus’s position). Although Erasmus’s carefully qualified skepticism about what he saw as a kind of fanatical denial of human achievement on Luther’s part may seem pragmatic or at least reasonable,[9] Luther in Germany and John Calvin in Geneva set the terms of the debate that occupied Dutch and British believers. For Calvin, the eternal and immutable fact of human damnation or salvation exists beyond the human capacity to reason with any degree of certainty. God decided at the beginning of time about each detail and intricately [10] planned all of creation. Since God is omnipotent and omniscient, God clearly knows what is in store for us in a way that we ourselves cannot. Again, to imagine that we can read “signs” of our election or reprobation in our personal experience of the world is to commit the ultimate idolatry — that is, to anthropomorphize God. God’s foreknowledge is not accessible to human beings, so no one can truly know whether she or he is saved; all human agency is therefore qualified by a knowledge of inborn sinfulness and an absolute predestination over which one can exercise very little influence through action. According to this belief about the absolute or “double predestination” from eternity — double, that is, in that God has ordained who will go to heaven and who to hell — the individual remains a corrupt vessel who attends to the divine vocation, and thus faithfully awaits a predetermined election. Such ideas about predestination, authority of scriptural text, and rejection of idolatry in human works form the nexus of Reformed belief as it took shape in Scottish Presbyterianism and disseminated gradually through English society through the tireless labors of reformers such as the Lutheran scholar William Tyndale, translator of the Bible into English from the original languages and martyr to the Protestant cause in 1536 on order from Henry VIII.[10] In fact, the issue of predestination was so fiercely contested in early modern England that “it represented an ideal shibboleth with which to expose and discomfort” evangelical Calvinists for those who wished to purge them from the English church.[11]

The “middle way” between Catholicism and Puritanism pursued by the English church from its settlement during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I involved elements of Calvinist doctrine, and indeed it was during her reign that radical Protestants produced the “Geneva Bible,” with its extensive and highly influential marginal glosses surrounding the text as a kind of interpretive buffer. (The Geneva Bible was published in Switzerland in 1560, but it was augmented as late as 1599 when the largest “Geneva” version was reprinted in London.) This version was widely used in households with more radical Protestant leanings, and as such it held a prominent place in the libraries of several of the authors included in this anthology, such as Elizabeth Clinton and Lucy Hutchinson. Much of the theology of the English church had been and continued to be influenced by the thought of the Continental reformers, even as many of the rituals and ceremonies of the state-sponsored church owed their form to Catholic antecedents. [11]

At the same time, the English settlement incorporated elements of anti-Calvinist thinkers, such as the Dutch theologian Jacob Arminius, who was attacked posthumously and labeled heretical by the Calvinist Synod of Dort for his resistance to several tenets of Calvinist orthodoxy. Claiming that defenders of predestination made God responsible for evil, Arminius disputed the doctrine of double predestination. Foreknowledge could be uncoupled from determinism, thereby clearing the way for the divine attributes of omnipotence and omniscience to be understood distinctly and differently. Human agency, in a qualified way, could return to the equation. During the reigns of Elizabeth’s successors to the English throne, King James I and his son, King Charles I, many Arminian preachers found favor in the court and were promoted to high ecclesiastical office. Many rose to power during the 1620s and played a crucial part in the Civil War crises that erupted in the following decades. Arminianism has been summarized in relation to its English context by the prominent historian of the movement, Nicholas Tyacke, as follows: “The essence of Arminianism was a belief in God’s universal grace and the free will of all men to obtain salvation.”[12]

In some respects replaying the debate as it had transpired in earlier incarnations — not just the Luther-Erasmus debate of the sixteenth century, but also the much earlier quarrel between Augustine and the British-born monk Pelagius in the fifth century — positions on free will and predestination provided the bases of both revolutionary and absolutist ideologies. The very meaning of human action, its efficacy and spiritual significance, had gone on trial in these at times abstruse yet vital theological debates. The question of freedom of agency, so crucial in the formation of religious belief and practice throughout the early modern period, took on major political consequences during the seventeenth century in England. These large-scale religious and political upheavals were intimately related to debates about the precise nature and causes of the Fall, in part because the Genesis narrative leaves open many provocative questions that were crucial to the theological debates about free will. Such questions include: who is to blame for original sin? Whose sin is greater, Adam’s or Eve’s? If God is omnipotent and omniscient, then how did evil come into being? Couldn’t an all-powerful deity have prevented the Fall somehow? Conversely, if Adam and Eve have free will, then how could God also have accurate foreknowledge of the Fall? As these kinds of questions indicate, the Genesis narrative had wide-ranging implications for almost all human behavior in early modern England. As a result, writings about the Fall were an especially powerful literary tool. By developing this particular story, writers from Aemilia Lanyer to Mary Chudleigh were able to debate, shape, and sometimes challenge the most significant cultural narratives of their day. [12]

Domestic Politics and the Woman Writer in Early Modern Society

Throughout the seventeenth century, theorists of monarchical government and those who opposed them incorporated biblical exegesis in support of their ideas. Often, the proponents of monarchy who tended toward absolutism blended a reading of the Bible with a patriarchal interpretation of the family. King James I, in a speech to Parliament on 21 March 1610, defends his claim of the divine right of kings by imagining a paternal authority granted to the monarch through the Bible: “In the Scriptures kings are called gods and so their power after a certain relation compared to the divine power. Kings are also compared to fathers of families for a king is truly Parens Patriae [the father of the country], the politic father of his people.”[13] Over the next several decades, Sir Robert Filmer mounted a massive defense of absolutism on the basis of a patriarchal analogy he derived from his reading of the Bible. As he argued in his Patriarcha, the subjection of children to their parents

is the only fountain of all regal authority, by the ordination of God himself. . . . This lordship which Adam by creation had over the whole world, and by right descending from him the patriarchs did enjoy, was as large and ample as the absolutest dominion of any monarch which hath been since the creation.[14]

The analogy Filmer advances is arrestingly simple: just as God granted Adam dominion over creation in Genesis 2:26, so God had endowed humanity with the rudiments of absolute government, the first of which began in Eden. In other words, what God gave Adam was patriarchal authority over all of creation, which included his family. Thus, in his later polemic on The Anarchy of a Limited or Mixed Monarchy, Filmer baldly claimed that, “by the appointment of God, as soon as Adam was created he was monarch of the world, though he had no subjects. . . . Eve was subject to Adam before he sinned. . . .”[15] By imagining the subjugation of Eve to Adam’s political authority even before the Fall, Filmer urged the institution of the nuclear family as an unblemished paradigm of sovereignty in government, a pattern made all the more necessary by the loss of innocence with the Fall and the disorder that ensued. In Filmer’s rhetoric, as in that of King [13] James I before him, the commandment to “honor thy father” (Exodus 20:12) extended outward from the domestic sphere to the highest levels of government.

The state-family homology thus governed conceptions of domestic life in early modern England. As Adam held command over Eve, so the monarch ruled the country, and the husband had power over his wife and family. A similar kind of analogy was popularly used in the post-Reformation period to connect the home with established religion. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century conduct books frequently argue that the home and the family should be a “little Church.”[16] The family, in other words, was viewed as an extension of the Church, a place where religious instruction should occur on a daily basis. According to this model, the ordering of the home — down to such seemingly mundane details as cleaning the house and managing servants — would ideally exhibit the piety associated with public religious practices, only in a more private manner. Because the domestic realm was expected to be a site of religious practice and women (even before the development of “separate sphere” ideology in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) were assumed to have more responsibility than men over household order, women were increasingly associated with religion and personal piety during the period.[17] As the Earl of Stirling famously argued, the “weaker sex” was “to piety more prone.”[18] Although assumptions like these clearly were founded on a belief in women’s inferiority, they also made it possible for women to pursue forms of expression that were culturally and religiously sanctioned.

Early modern women made use of this opportunity for public discourse by writing on religious subjects. Despite conventional pronouncements that they should be “chaste, silent, and obedient,” women in this period wrote and published texts in quite surprising numbers. As early as 1985, it was estimated that over 650 first editions were published by women in the seventeenth century; many more texts have been uncovered since then, and we now know that many additional works were circulated in manuscript.[19] The centrality of religious discourse and the fact that, like the spiritual management of the home, religious writing was deemed more suitable for women than other forms of writing meant that women wrote and published on religious subjects more than any other topics in the period. Such religious writings comprised a wide range of fictional [14] and nonfictional genres, including prayers, prose and verse meditations, epic poems, advice books, and lyric poetry. This formal diversity is reflected in more specific narratives of the Fall, as the contents of our anthology make clear. From Dorothy Leigh’s advice to her children to the polemical tracts of Esther Sowernam and Mary Astell and the epic poetry of Mary Roper and Lucy Hutchinson, women deployed a remarkably wide range of genres and literary techniques to express their attitudes about religious belief in general, and the Genesis narrative in particular.

Women’s ideas and opinions about the Fall and its implications for their lives were also disseminated in many forms. Many found their way into print, some were published through the circulation of manuscripts, and others were shared among a small circle of intimates or kept private. Because no clear hierarchy existed among different forms of publication — print, manuscript, and oral recitation being the most common — one cannot infer from the form in which these works have survived any special prestige that early modern readers would have accorded their publication, which was at times initially anonymous, as in the case of the first five cantos of Lucy Hutchinson’s biblical epic, Order and Disorder. Indeed, contrary to modern suppositions about the prestige of print publication, many writers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries shunned print, either with the genuine belief or quasi-aristocratic affectation that public appearance in print was undignified for the words of a person of noble birth. Among our selections, one sees this theme dramatized to great effect in relation to the Fall in Katherine Philips’s poem, the full title of which in manuscript conveys the sense of social risk involved in publication: “To Antenor, on a Paper of Mine, Which an Unworthy Adversary of his Threatened to Publish, to Prejudice Him in Cromwell’s Time.”

As Philips’s title subtly suggests, manuscript circulation provided an alternative and at times preferred mode of publication throughout the early modern period.[20] Oral performance, too, would have been a much more pervasive means of reading for works written by both women and men, a fact of the times which may help to explain the existence of so-called “closet dramas” such as Elizabeth Cary’s Tragedy of Miriam, the Fair Queen of Jewry (1613), the earliest surviving drama known to have been composed by an Englishwoman.[21] What is clear enough from the evidence of the texts included in this anthology is that one cannot generalize too reductively about the conditions of literary production for women (nor for men, for that matter) during the early modern period. In whatever material form texts by early modern Englishwomen reached their eventual [15] audiences, those that were written down and preserved for posterity in one form or another register a great diversity of attitudes toward the biblical narrative, revealing contradictions and variations that mark their authors’ positions in post-Reformation English culture.

Editorial Policies

This anthology is intended primarily for student readers and (if we may say so hopefully) a more general public. Our primary goal in editing these texts has therefore been to make them as readily available as possible to modern readers without compromising the basic structure or meaning of the originals. We have standardized, Americanized, and lightly modernized spelling, punctuation, capitalization, italics, and paragraphing format. We also expand abbreviations and contractions and correct manuscript irregularities when necessary to make these works more accessible for university-level students. Archaic verb endings (e.g. -eth) have been retained, as have some archaic words, though these are always glossed. The titles of early modern texts have been modernized to conform to standard American usage. We have provided explanatory notes for all obsolete and obscure words as well as for text in foreign languages, and we identify the most relevant biblical, classical, and historical allusions whenever possible. In addition, we have made every effort to provide brief accounts of the intellectual and political histories necessary to explicate these works. All glosses of words and phrases derive from the Oxford English Dictionary. Unless otherwise indicated, the biographical material found in Appendix 4 is taken from the Dictionary of National Biography. The material on Dorothy Calthorpe was generously provided by Julie A. Eckerle.

It is important for students to realize that any modernization of an early modern text — however trivial or minute it may seem — may potentially influence the meaning of that text. For example, given the idiosyncrasies of early modern capitalization practices, when Bathsua Makin writes in her original treatise that it would be “a piece of Reformation” to correct the current practices of educating women, does she mean simply that such educational reforms would be welcome, or does she imply more specifically that such changes would either directly or indirectly participate in the ongoing process of the Protestant Reformation in England? In our modernized edition, the word “reformation” appears in lower-case, but students curious about such details can seek out the original printed edition of An Essay to Revive the Ancient Education of Gentlewomen, widely available in facsimile, for comparison. We encourage interested students to consult our Selected Bibliography for the original printed and manuscript editions of these texts as well as a list of modern scholarly editions and anthologies, which can provide additional resources for further research. [16]

Many anthologies and readers published in recent years that focus on early modern women and their writings have generally tended to include only short excerpts from primary texts as an inducement to further primary-source research.[22] Unfortunately, short extracts discourage students and teachers from fully discussing the wide range of meanings, contexts, and rhetorical strategies, with which these texts, taken in their entirety, invite us as readers to engage. In order to make Early Modern Women on the Fall: An Anthology as useful as possible to college teachers and students, we have chosen not to rely on brief excerpts from longer works, but to include texts in their entirety whenever possible. The majority of texts in this volume, therefore, are printed in complete versions, meaning that we either include longer works in their entirety (including those such as Clinton’s The Countess of Lincoln’s Nursery that are not usually read in the context of the Fall) or we include the complete text of individual poems (such as those by Cavendish, Philips, and Roper) that originally appeared in longer print or manuscript collections. Exceptions to this are in the works of Lanyer, Leigh, and Sowernam, which we have chosen to excerpt because full versions of these texts are easily accessible in modern editions.[23] Mary Roper’s poem “The Creation of Man” appears in print for the first time in our edition, as does the complete section of her poem on “Man’s Shameful Fall” and the recently discovered “A Description of the Garden of Eden,” by Dorothy Calthorpe. Textual details about all the works in our anthology, including information about the existence of manuscript versions and the original placement of excerpted selections, are given in Appendix 4. In editing these texts for the classroom, our goal has been [17] to make them readily available and comprehensible to readers at various stages in their education, and we hope that by modernizing them, we might bring some fresh perspectives to the consideration of early modern women’s writing as well as early modernity itself.

Suggestions for Using this Book

Why focus exclusively on women writers’ responses to the Fall? One important reason has to do with problems of access. Male positions on the Fall from this period have for many generations been widely published in numerous collections and editions. Ultimately, our goal is emphatically not to re-segregate women’s writing from men’s writing or to replace one with the other but, on the contrary, to encourage that these texts be read in conjunction with male-authored texts from the period, such as Paradise Lost. Recent trends in Milton studies have focused on analyzing and teaching Milton’s account of the Fall alongside those of seventeenth-century female authors, most notably Aemilia Lanyer and Lucy Hutchinson. For example, Shannon Miller’s Engendering the Fall: John Milton and Seventeenth-Century Women Writers considers how female authors both influenced and reworked Milton’s epic narrative of Adam and Eve in order to engage with central questions of political legitimacy in the period.[24] And in “Diabolic Dreamscape in Lanyer and Milton,” Josephine A. Roberts suggests a classroom strategy for teaching these two authors side-by-side that emphasizes both their divergent interpretations of Eve’s act of disobedience as well as their similarities in “reacting against the misogynist tradition.”[25] As a companion volume for teachers and students of Milton, Early Modern Women on the Fall: An Anthology seeks to further these scholarly and pedagogical explorations of Milton’s writings that locate him within the context of his female contemporaries. [18]

In addition to aiding the scholarly dialogue between readers of celebrated male authors, such as John Milton and John Donne, and of less-known women writers, we hope that this anthology might also serve readers’ needs as a freestanding collection of unique sources for the study of religion, politics, gender, and literary art. Our volume includes the works of eighteen female authors spanning the seventeenth century, with a few texts that may precede this century and one that follows it by a couple of years. These writers represent a range of political and doctrinal positions: Jane Barker was a Roman Catholic and Jacobite supporter, for example, while Lucy Hutchinson was deeply committed to the Puritan revolution. The diversity of these texts and their authors will allow teachers and students to discuss both how confessional and political differences influenced representations of the Fall and how these texts might have fed back into the culture at large, producing new ideas about religion or social change.

Some of the texts we include in our anthology (such as Rachel Speght’s A Muzzle for Melastomus, 1617) have frequently been read within the context of the “pamphlet debates” about women that were popular in the early seventeenth century. These debates, also known by the French phrase querelle des femmes, focused broadly on the proper role of women in early modern society. Especially during the first two decades of the seventeenth century, printed attacks on women were quickly followed by the publication of defenses of women’s nature that focused on such issues as women’s education, female sexuality, and the appropriate behavior of good wives.[26] Partly because the circumstances that provoked women’s responses to the debate often involved sermons and invectives against women by male preachers, we aim to resituate these texts within the contexts of their most immediate and specific debates about the Fall, and therefore to enable students to trace the development of this scriptural debate over the course of the early modern period.

This volume will also enable a different kind of analysis, one focused on the logical, rhetorical, symbolic, political, religious, or social function of the Fall story within an individual text. Many of the writers in the volume use the story of the Fall as a jumping-off point or as one piece in a complex rhetorical picture. Elizabeth Clinton’s Countess of Lincoln’s Nursery is a good example of such a text. On the surface, her treatise seems to have little to do with scriptural debates about Eve and human sin, given that her primary motive is to warn aristocratic women about the dangers of hiring wetnurses to feed their infant children. However, Clinton’s treatise, which argues that women have “followed Eve in transgression” and should, therefore, “follow her in obedience,” is in many ways directly connected to issues of the Fall, as it uses the context of Eve’s sin and subsequent punishment in order to analyze an important issue in seventeenth-century English theology and social life: the nature of women’s post-lapsarian bodily [19] and reproductive responsibilities. Similarly, both Bathsua Makin and Mary Astell use the Fall narrative — particularly its emphasis on Eve’s decision to eat from the forbidden Tree of Knowledge — to comment on and advocate for women’s education. The speaker of Jane Barker’s “Farewell to Poetry” likewise employs the story to explain why women “To pains and ignorance are most accursed,” but finds herself saved from the familiar form of “expatiating thus” by a famous pair of early modern physicians, who take her on a fantastic voyage of sorts through the human body, as if scientific knowledge could at least compensate in some way for the lapse into knowledge of good and evil at the Fall. For these writers as for the other authors included in this anthology, in other words, the arguments, images, and discursive contexts that surround these retellings of the Fall are often just as important as the story itself. Read in their entirety, these texts demonstrate the wide range of cultural analyses and debates that the Genesis narrative made possible for women writing in the early modern period.

In bringing together an array of women’s narratives on the Fall, this volume makes it possible for readers to compare and contrast different versions of this story as told by women throughout the early modern period. For example, by reading complete versions of many of these texts, students will be in a better position to trace references that recur frequently throughout the volume (including not only the Genesis narrative but also the epistles of St. Paul and texts from classical antiquity) and to analyze the significance of these allusions as they take note of different responses to the same set of proof-texts. To further encourage this kind of comparative reading and attention to intertextuality, we have included in the appendices the full text of the creation story from Genesis (in both the Geneva and King James versions). We invite readers not only to compare women’s narratives of the Fall to the versions of Genesis available to early modern readers, but to compare the Geneva and King James versions with one another. The Geneva version was first printed in 1560, and it was the primary Bible used by sixteenth-century Protestants in the British Isles. In the seventeenth century, especially after the King James version became available, the Geneva Bible was preferred by more radical Protestants. The King James version was first conceived at the Hampton Court Conference of 1604 under the direction of King James I and was published in 1611. This new “authorized version” of the Bible was designed to correct perceived problems in earlier English translations, including the Geneva Bible, which James thought “the worst of all” English Bibles because it seemed to authorize sedition.[27] These two versions offer at times subtle, [20] at times striking differences in translation that should provide the basis for comparative analysis and classroom discussion.

Also included as Appendix 3 is the complete text of The Form of Solemnization of Matrimony, from the Book of Common Prayer (1559), the prayer book that formed the basis for the practices of the English church during the early modern period and continues to do so in Anglican worship today. The text of the marriage service that we include was used during Elizabeth’s reign and throughout the seventeenth century (with some modifications introduced in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer), and it provides students with another key text of the period that deploys the story of Adam and Eve for specific social and religious purposes. Specifically, readers might use this text to consider in more detail how ideas about marriage and the subordination of women were tied up with the story of the Fall, an ideological connection also made by several of women authors in this volume, including Aemilia Lanyer, Lady Anne Southwell, and Sarah Fyge.

To promote similar kinds of contextual engagement with these authors, we have decided to include an appendix (Appendix 4) with brief biographical and textual sketches of each author rather than providing this material as a headnote to each text. One of the primary goals of this anthology is to encourage thematic, theoretical, and religious readings of these texts and authors and to invite students to be participants in different kinds of discussions about how the Fall narrative is used in various literary contexts. However, it is often the case that the work of early women writers is read primarily (and sometimes exclusively) in terms of the author’s biographical information, at the expense of other important contexts. In part, this tendency to analyze seventeenth-century women’s writing in biographical terms is attributable to the development of women’s writing as a specific field of study within early modern literature. When scholars and teachers first began the work of recovering these texts and bringing them to public attention, often for the first time, so little was known about many of these writers that a biographical approach was often both productive and necessary. Now that early modern women’s writing has become a more fully developed critical and pedagogical field (as our Selected Bibliography can attest), we feel that it is important to continue efforts to de-emphasize women’s lives as the sole context for reading their writings by placing their writings in a nexus of contemporary religious and social texts and contexts. By placing biographical information about authors in an appendix, we encourage students and teachers to consult this material and to use it in their teaching and research, but at the same time we resist the tendency to privilege the biographical as a default category of analysis. [21]

Finally, by organizing our volume chronologically, we encourage readers to make comparisons across the “long seventeenth century” and to note historical changes in both the mode and content of scriptural exegesis. That is, this collection is not just about a treasure hunt for a trope, but about the prevalence of the Fall as a central discourse that women writers grappled with throughout the period, showcasing in the process a wide ranges of genres, rhetorical strategies, and political vantage points. Accessing the attitudes of women readers as they engage the foundational texts of Christianity, students will gain a unique vantage from which to witness early modern women becoming writers and reconstituting gender categories. Furthermore, we hope that the thematic focus of this anthology will encourage students to engage not only with the texts that women wrote but with the central questions pertaining to religion and gendered subjectivity that they debated.

- Margaret Atwood, The Penelopiad (New York: Cannongate, 2005); Ursula K. Le Guin, Lavinia: A Novel (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2008). In this connection, see also the recent scholarly work of Laurie Maguire, Helen of Troy: From Homer to Hollywood (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), who notes that “The story of Helen is a story of withdrawal” (12). ↵

- The key source on these matters, however, is to be found in the later writings of Augustine, City of God, Book 14, trans. Henry Bettenson (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972), 547–94, though Augustine himself claims the authority of St. Paul’s Epistles to the Romans and Galatians in particular as his sources; Augustine treats the effect of original sin on infants in City of God 16.27, 688–89. For a helpful introduction to Augustine’s role in the development of Western attitudes toward sexuality and gender, see Peter Brown, The Body and Society: Men, Women, and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), 387–427. Students of English literature will find an excellent starting point for considering early modern attitudes toward original sin in James Grantham Turner, One Flesh: Paradisal Marriage and Sexual Relations in the Age of Milton (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987). ↵

- For accounts of the ways in which religion continues to shape our contemporary lives, see the contributions by Mark C. Taylor, Donald S. Lopez Jr., Bruce Lincoln, and Gustavo Benavides in Critical Terms for Religious Studies, ed. Mark C. Taylor (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). ↵

- For an excellent account of the effects of religious, social, and political upheaval during the Civil Wars on English literature, see David Loewenstein and John Morrill, “Literature and Religion,” in The Cambridge History of Early Modern English Literature, ed. David Loewenstein and Janel Mueller (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 664–713. ↵

- See the essays collected in Milton and Toleration, ed. Sharon Achinstein and Elizabeth Sauer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), for an up-to-date assessment of this dynamic and its implications for literature and society. ↵

- See Alister E. McGrath, The Intellectual Origins of the European Reformation, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004) for a learned account of the roots of the movement, and esp. 29–33 for an explanation of the problems that confront historians seeking to narrate the emergence of Protestantism in relation to the late medieval church. ↵

- Martin Luther, Selections from His Writings, ed. John Dillenberger (New York: Anchor Books, 1958), provides representative excerpts from across the corpus in a widely available translation. ↵

- The texts are readily available in the Library of Christian Classics edition, Luther and Erasmus: Free Will and Salvation, ed. and trans. E. Gordon Rupp and Philip S. Watson (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1969). The literary character of the exchange is meticulously reconstructed by Brian Cummings, The Literary Culture of the Reformation: Grammar and Grace (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 144–83. ↵

- For the argument that the problem of finding a criterion for truth arose out of the intellectual crisis of the Reformation, and in particular, from Erasmus’s skeptical defense of the Catholic faith against Luther, see Richard H. Popkin, The History of Scepticism from Erasmus to Spinoza, rev. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), 1–17. ↵

- Two recent student-oriented collections of materials pertaining to early modern English religion deserve mention here: Religion and Society in Early Modern England: A Sourcebook, ed. David Cressy and Lori Anne Ferrell (London and New York: Routledge, 1996); and Voices of the English Reformation: A Sourcebook, ed. John N. King (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004). ↵

- Peter Lake, “Calvinism and the English Church 1570–1635,” in Reformation to Revolution: Politics and Religion in Early Modern England, ed. Margo Todd (London and New York: Routledge, 1995), 180–207, esp. 188. ↵

- Nicholas Tyacke, “Puritanism, Arminianism, and Counter-Revolution,” in Reformation to Revolution, ed. Todd, 53–70, esp. 54. ↵

- James I, Works (London, 1616), 529. ↵

- Sir Robert Filmer, Patriarcha and Other Writings, ed. Johann P. Sommerville (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 7. Filmer’s treatise remained unpublished until 1680, when it was printed as Tory propaganda, but Filmer wrote it, according to his editor, from the late 1620s through the early 1640s. ↵

- Filmer, The Anarchy of a Limited or Mixed Monarchy (1648), in Patriarcha and Other Writings, ed. Sommerville, 144–45. ↵

- See for example William Gouge, Of Domestical Duties (London, 1622) and William Perkins, Christian Economy (London, 1609). ↵

- For women and personal piety, see Christine Peters, Patterns of Piety: Women, Gender and Religion in Late Medieval and Reformation England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003). For women as responsible for household order, see Robert Cleaver, A Godly Form of Household Government (London, 1598). ↵

- Recreations with the Muses (London, 1637), 107. ↵

- See Patricia Crawford, “Women’s Published Writings, 1600–1700,” in Women in English Society, 1500–1800, ed. Mary Prior (London and New York: Routledge, 1985), 211–82. ↵

- See Harold Love, The Culture and Commerce of Texts: Scribal Publication in Seventeenth-Century England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998). ↵

- Elizabeth Cary, the Lady Falkland, The Tragedy of Miriam, Fair Queen of Jewry, ed. Barry Weller and Margaret W. Ferguson (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994). ↵

- See for example The Cultural Identity of Seventeenth-Century Woman: A Reader, ed. N.H. Keeble (London: Routledge, 1994) and Reading Early Modern Women: An Anthology of Texts in Manuscript and Print, 1550–1700, ed. Helen Ostovich and Elizabeth Sauer (London and New York: Routledge, 2003). ↵

- For the full text of Lanyer’s book, see The Poems of Aemilia Lanyer: Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, ed. Susanne Woods (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993). The complete text of Leigh’s treatise is included in Women’s Writing in Stuart England, ed. Sylvia Brown (Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing, 1999), 3–87. Sowernam’s treatise is included in Defenses of Women: Jane Anger, Rachel Speght, Ester Sowernam and Constantia Munda, in The Early Modern Englishwoman: A Facsimile Library of Essential Works, part 1, vol. 4, sel. and intro. Susan Gushee O’Malley (Aldershot: Scholar, 1996) and in Half Humankind: Contexts and Texts of the Controversy about Women in England, 1540–1640, ed. Katherine Usher Henderson and Barbara F. McManus (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1985), 217–43. Hutchinson’s Order and Disorder raises a more complex set of issues, however. The first five cantos of Hutchinson’s poem, included in our volume, were published in 1679 in what appears to be a complete version of the text. Indeed, line 5.673 of Order and Disorder reads: “With these most certain truths let’s wind up all.” However, a much longer version of the epic (in twenty cantos) exists in manuscript, which David Norbrook prints in its entirety in his edition: Order and Disorder, ed. David Norbrook (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001). See Appendix 4 for more textual details. ↵

- This fruitful interaction has gradually emerged as a vital concern in the secondary literature on Milton; see Shannon Miller, “Serpentine Eve: Milton and the Seventeenth-Century Debate Over Women,” Milton Quarterly 42 (2008): 44–68; and Engendering the Fall (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008). A founding work still valuable for its insights into women’s reception of Milton in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century is Joseph Wittreich, Feminist Milton (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987). ↵

- Roberts, “Diabolic Dreamscape in Lanyer and Milton,” in Teaching Tudor and Stuart Women Writers, ed. Susanne Woods and Margaret Hannay (New York: MLA, 2000), 299–302, esp. 302. On pairing Milton with women writers in the classroom, see also Betty S. Travitsky and Anne Lake Prescott, “Juxtaposing Genders: Jane Lead and John Milton,” in Teaching Tudor and Stuart Women Writers, ed. Woods and Hannay, 243–47. ↵

- For a good overview of these debates, see the introduction to Half Humankind, ed. Henderson and McManus, 3–46. ↵

- A good overview of the issues involved, including James’s anger at the marginal commentary included in the Geneva translation, can be found in Gerald Hammond, “Translations of the Bible,” in A Companion to English Renaissance Literature and Culture, ed. Michael Hattaway (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2000), 165–75, esp. 167. For the role of the production of Bibles in early modern Protestantism, see the essays collected in The Bible as Book: The Reformation, ed. Orlaith O’Sullivan (London and New Castle, DE: The British Library and Oak Knoll Press, 2000). On the King James version, see also Gordon Campbell, Bible: The Story of the King James Version, 1611-2011 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); and David Norton, The King James Bible: A Short History from Tyndale to Today (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011). ↵