[print edition page number: 257]

Sarah Fyge

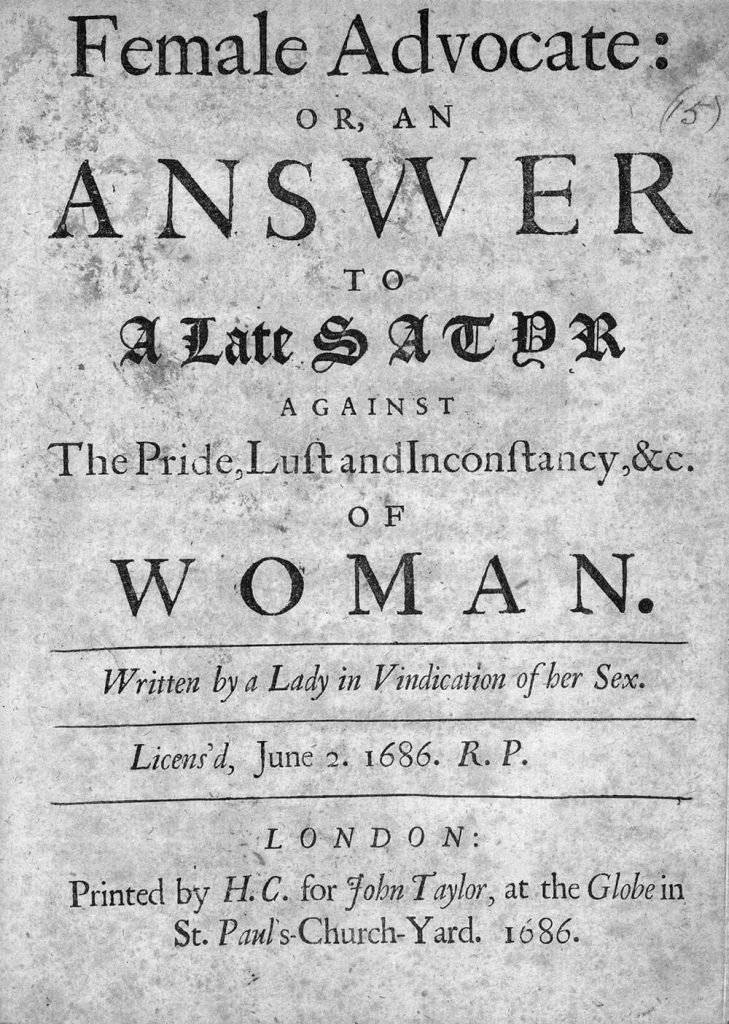

The Female Advocate: or, An Answer to a Late Satire against the Pride, Lust, and Inconstancy of Woman (1687)[1]

Reproduced by permission of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

To the Reader

That which makes many books come abroad into the world without Prefaces is the only reason that incites me to one: viz. the smallness of them. Being willing to let my reader know why this is so: for as one great commendation of our sex is to know much and speak little, so an intelligent modesty informs my soul, I ought to put a period to the intended length of the ensuing lines, lest censuring critics should measure my tongue by my pen and condemn me for a “talkative” by the length of my poem. Though I confess the illustrious subject requires (nay, commands) an enlargement from any other pen than mine (or those under the same circumstances), but I think it is good frugality for young beginners to send forth a small venture[2] at first and see how that passes the merciless ocean of critics, and what return it makes, and so accordingly adventure the next time. I might, if I pleased, make an excuse for the publication of my book, as many others do. But then, perhaps, the world might think ’twas only a feigned unwillingness. But when I found I could not hinder the publication,[3] I set a resolution to bear patiently the censures of the world, for I expected its severity, the first copy being so ill writ, and so much blotted, that it could scarce be read; and they that had the charge of it, in the room of blots, writ what they pleased, and much different from my intention. I find the main objection is that I should answer so rude a book when, if it had not been against our sex, I should not have read it, much less have answered it. But I think its being so required the sharper answer and severer contradictions. I suppose some will think the alterations occasioned [258] by their dislike of the former. If that had been intended for the press, some things there inserted had been left out, which I have now done; though they might pass well enough in private, they were not fit to be exposed to every eye. But I think, when a man is so extravagant as to damn all womankind for the crimes of a few, he ought to be corrected. But in his second edition, he hath been more favorable, yet there he goes beyond the bounds of modesty and civility, and exclaims not only against virtue, but moral honesty, too, and supposes he hath banished all goodness out of them. But it will be an impossible thing, because they are more essentially good than men. For ’tis observed in all religions, that women are the truest devotionists and the most pious, and more heavenly than those who pretend to be the most perfect and rational creatures. For many men, with conceit of their own perfections, neglect that which should make them so, as some mistaken persons who think if they are of the right church they shall be infallibly saved when they never follow the rules which lead to salvation. And when persons with this inscription pass current[4] in Heaven, then should it be according to my antagonist’s fancy, that all men are good and fitting for Heaven, because they are men; and women are irreversibly damned, because they are women. But that Heaven should make a male and female, both of the same species, both endued[5] with the like rational souls, for two such differing ends, is the most notorious principle, and the most unlikely of any that ever was maintained by any rational man. And I shall never take it for an article of my faith, being assured that Heaven is for all those whose purity and obedience to its law qualifies them for it, whether male or female; to which place the latter seem to have the justest claim, is the opinion of one of its votaries.[6]

Reproduced by permission of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Blasphemous wretch![7] How canst thou think or say

Some cursed or banished fiend usurped the sway[8]

When Eve was formed? For then’s denied by you

God’s omnipresence and omniscience, too,

Without which attributes he could not be 5

The greatest and supremest deity.

Nor can Heav’n sleep, though it may mourn to see

Degen’rate man speak such vile blasphemy.When from dark Chaos Heav’n the world did make,

And all was glorious it did undertake, [259] 10

Then were in Eden’s garden freely placed

Each thing that’s pleasant to the sight or taste.

’Twas filled with beasts and birds, trees hung with fruit,

That might with man’s celestial nature suit.

The world being made thus spacious and complete, 15

Then man was formed, who seemed nobly great.

When Heav’n surveyed the works that it had done,

Saw male and female, but found man alone,

A barren sex, and insignificant,

Then Heav’n made woman to supply the want, 20

And to make perfect what before was scant.

Surely then she a noble creature is,

Whom Heav’n thus made to consummate all bliss.

Though man had being first, yet methinks she

In nature should have the supremacy; 25

For man was formed out of the dull senseless earth,

But woman had a much more noble birth.

For when the dust was purified by Heaven,

Made into man, and life unto it given,

Then the almighty and all-wise God said 30

That woman of that species should be made;

Which was no sooner said, but it was done,

’Cause ’twas not fit for man to be alone.[9]Thus have I proved woman’s creation good,

And not inferior, when right understood, 35

To that of man’s. For both one maker had

Which made all good; then how could Eve be bad?

But then you’ll say, though she at first was pure,

Yet in that state she did not long endure.

’Tis true. But yet her fall examine right. 40

We find most men have banished truth for spite.

Nor is she quite so guilty as some make,

For Adam most did of the guilt partake:

While he from God’s own mouth had the command,

But woman had it at the second hand.[10] 45

The Devil’s strength weak woman might deceive,

But Adam only tempted was by Eve.

She had the strongest tempter and least charge;[11]

Man’s knowing most doth make his sin more large. [261]

But though that woman man to sin did lead, 50

Yet since her seed hath bruised the serpent’s head.[12]

Why should she thus be made a public scorn

Of whom the great Almighty God was born?

Surely to speak one slighting word must be

A kind of murmuring impiety? 55

But yet their greatest haters still prove such

Who formerly have lovèd them too much.

And from the proverb they are not exempt,

“Too much familiarity has bred contempt.”[13]

And as in Adam all mankind did die,[14] 60

They make all base for one’s immodesty;

Nay, make the name a kind of magic spell,

As if ’twould conjure married men to hell.Woman! By Heaven, the very name’s a charm

And will my verse against all critics arm. 70

The Muses or Apollo[15] doth inspire

Heroic poets; but yours is a fire

Pluto from hell did send by incubus[16]

Because we make their hell less populous,

Or else you ne’er had damned the females thus. 75

But if so universally they are

Disposed to mischief, what need you declare

Peculiar faults, when all the world might see

With each approaching morn a prodigy?[17]

Man curse bad woman! I could hear as well 80

The black infernal devils curse their hell,

When there had been no such damned place we know,

If they themselves had not first made it so.

In lust perhaps you others have excelled, [262]

And made all whores that possibly would yield, 85

And courted all the females in your way,

Then did design at last to make a prey

Of some pure virgins; or what’s almost worse,

Make some chaste wives to merit a divorce.

But ’cause they hated your insatiate mind, 90

Therefore you call what’s virtuous “unkind.”

And disappointments did your soul perplex,

So in mere spite you curse the female sex.

I would not judge you thus, only I find

You would adult’rate[18] all womankind, 95

Not only with your pen. You higher soar:

You’d exclude marriage, make the world a whore.But if all men should of your humor[19] be,

And should rob Hymen[20] of his deity,

They soon would find the inconveniency. 100

Then hostile spirits would be forced to peace

Because the world so slowly would increase.[21]

They would be glad to keep their men at home,

And every king want more t’attend his throne.

Nay, should an English prince resolve that he 105

Would keep the number of’s nobility,

And this dull custom some few years maintained,

There would be none less than a peer i’th’land.

And I do fancy, ’twould be pretty sport

To see a kingdom crammed into a court. 110

Sure a strange world, when one shall nothing see,

Unless a bawdy-house or nunnery.[22]

For should this act e’er pass, woman would fly

Unto dark caves to save her chastity.

She only in a marriage bed delights; 115

The very name of “whore” her soul affrights;

And when that sacred ceremony’s gone,

Woman (I’m sure) will choose to live alone.

There’s none can number all those virtuous dames

Which chose cold death before their lovers’ flames. 120

The chaste Lucretia, whom proud Tarquin loved: [263]

Herself she slew, her chastity she proved.[23]

But I’ve gone further than I need have done,

Since we have got examples nearer home:

Witness those Saxon ladies who did fear 125

The loss of honor when the Danes were here

And cut their lips and noses, that they might

Not pleasing seem, or give the Danes delight;[24]

Thus having done what they could justly do,

At last they fell their sacrifices too. 130

I could say more, but history will tell

Many examples that do these excel.In constancy they often men excel,

That steady virtue in their souls do dwell.

She’s not so fickle and frail as men pretend 135

But can keep consistent to a faithful friend;

And though man’s always alt’ring of his mind,

He says inconstancy’s in womankind

And would persuade us that we engross all

That’s either fickle, vain, or whimsical. 140

Man’s fancied truth small virtue doth express:

Ours is constancy; theirs is stubbornness.

In faithful love our sex do them outshine

And is more constant than the masculine.

For where is there that husband that e’er died, 145

Or ever suffered, with his loving bride?

But num’rous trains of chaste wives oft expire

With their dear husbands wrapped in flaming fire —

We’d do the same if custom did require.

But this is done by Indian women, who 150

Do make their constancy immortal, too,

As is their fame; while happy India yields

More glorious phoenix than th’Arabian fields.[25]

The German women constancy did show

When Wensberg was besieged, begged they might go [264] 155

Out of the city with no bigger packs

Than each of them could carry on their backs.[26]

The wond’ring world expected they’d have gone

Laden with treasures from their native home;

But crossing expectation, each did take 160

Her husband, as her burden, on her back;

So saved him from intended death, and she

At once gave him both life and liberty.

How many loving wives have often died

Through extreme grief by their cold husbands’ side? 165

If this ben’t[27] constancy, why then the sun

Or earth do not a constant progress run.There’s thousands of examples that will prove

Woman is true and constant in chaste love.

But when to us pretended love is made, 170

We yielding find it lust in masquerade.

Then we disown it — virtue says we must;

We well may change; I think the reason just.

“Change” did I say? That word I must forbear.

No, the bright star won’t wander from her sphere 175

Of virtue (in which female souls do move),

Nor will she join with an insatiate love.

For she that’s first espoused to virtue must

Be most inconstant when she yields to lust.But now the scene is altered, and those who 180

Were esteemed modest by a blush or two

Are represented quite another way,

Worse than mock-verse doth the most solid play.

She that takes pious precepts for her rule

Is thought, by some, a kind of ill-bred fool; 185

They would have all bred up in Venus-school.[28]

And if that by her speech or carriage she

Doth seem to have sense of a deity,[29] [265]

She straight is taxed with ungentility,

Unless it be that little blinded boy, 190

Cupid, that childish God, that trifling toy,

That certain nothing, whom they feign to be

The son of Venus, daughter to the sea.[30]

But were he true, none serve him as they should,

For commonly those who adore this god 195

Do’t only in a melancholy mood;

Or else a sort of hypocrites they are

Who invocate him only as a snare,

And by him they do sacred love pretend,

When, as Heav’n knows, they have a baser end. 200Nor is he god of love; but if I must

Give him a title, he’s the god of lust.

And surely woman impious must be,

Whene’er she doth become his votary,

Unless she will believe without control 205

Those that did hold a woman had no soul;[31]

And then doth think no obligation lies

On her to act what may be just or wise,

And only strive to please her appetite

And to embrace that which doth most delight. 210

And when she doth this paradox believe,

Whatever faith doth please she may receive.

She may be Turk, Jew, atheist, infidel,

Or anything, ’cause she need fear no hell;

For if she hath no soul, what need she fear? 215

Something, she knows not what, or when, or where.But hold, I think I should be silent now

Because a woman’s soul you do allow.

But had we none, you’d say we had, else you [266]

Could never damn us at the rate you do. 220

What, dost thou think thou hast a privilege given,

That those whom thou dost bless shall mount to Heaven?

And those thou cursest, unto hell must go?

And so dost think to fill th’abyss below

Quite full of females, hoping there may be 225

No room for souls as big with vice as thee.

But if that thou with such vain hopes shouldst die,

I’th’fluid air thou must not think to fly,

Or enter into Heav’n; thy weight of sin

Would crush the damned, and so thou’dst enter in. 230

But hold, I am uncharitable here:

Thou mayst repent, though that’s a thing I fear.

But if thou shouldst repent, why then again

It would at best but mitigate thy pain

Because thou hast been vile to that degree 235

That thy repentance must eternal be.

For wert thou guilty of no other crime

Than what thou lately puttest into rhyme —

Why that, were there no more offenses, given

Were crime enough to shut the gate of Heaven. 240

But put together all that thou dost do,

It will not only shut, but bar it, too.When wise Heav’n made woman, it designed

Her for the charming object of mankind.

And surely man degenerate must be 245

That doth deny our native purity.

Nor is there scarce a thing that can be worse

Than turning of a blessing to a curse.

’Tis to make Heav’n mistaken when you say

It meant, at first, what proves another way. 250

For woman was created good, and she

Was thought the best of frail mortality,

An help for man,[32] his greatest good on earth,

Made for to sympathize his grief and mirth.

Then why should man pretend she’s worse than hell, 255

The only plague o’th’world, and in her dwell

All that is base or ill. No, she’s not so.

Rather, she is the greatest good below,

Most real virtue and true happiness,

His only steady and most constant bliss. [267] 260I must confess there are some bad, and they

Led by an ignis fatuus[33] go astray.

All are not forced to wander in false way;

Only some few, whose dark benighted sense,

For want of light, han’t[34] power to make defense 265

Against those many tempting pleasures, which

Not only theirs, but masculine souls bewitch.

But you’d persuade us that ’tis we alone

Are guilty of all crimes, and you have none,

Unless some few, which you call fools (who be 270

Espoused to wives and live in chastity),

But the most rational, without which we

Doubtless should question your humanity.

And I would praise them more, only I fear

If I should do it, ’twould make me appear 275

Unto the world much fonder than I be

Of that same state, for I love liberty.

Nor do I think there’s a necessity

For all to enter beds, like Noah’s beast

Into his ark; I would have some released 280

From the dear cares of that same lawful state,

But I’ll not dictate; I’ll leave all to fate.

Yet do I think a single life is best

For those that love to contemplate at rest,

For then they’re free from trifling toys, and may 285

Uninterrupted nature’s works survey.Had my antagonist but spent his time

Making true verse instead of spiteful rhyme,

As a small poet, he had gained some praise,

But now his malice blasts his twig of bays.[35] 290

I do not wish you had, for I believe

It is impossible for to deceive

Any with what you write because that you

Do only insert things supposèd true.

And if by supposition I may go, 295

Then I’ll suppose all men are wicked, too,

Since I am sure there are so many so.

And ’cause you have made whores of all you could,

So, if you durst, you’d say all women would; [268]

Which words do only argue guilt and spite: 300

All makes you cheap in ev’ry mortal’s sight.

And it doth show that you have always been

Only with women guilty of that sin.

You ne’er desired, nor were you fit for those

Whose modest carriage doth their minds disclose, 305

And, Sir, methinks you do describe so well

The way and manner Bewley[36] entered hell,

As if your love for her had made you go

Down to the black infernal shades below.But I suppose you never was so near — 310

Nay, if you had, you scarce would have been here.

For had they seen you, they had kept you there

Unless they thought, whene’er it was you came,

Your red hot entrance might increase the flame

(If burning hell add to their extreme pain), 315

And so were glad to turn you off again.There’s one thing more I do believe beside

Might be occasioned by their haughty pride.

They knew you rivaled them in all their crimes,

Wherewith they could debauch the wiling times. 320

And as fond mortals hate a rival, they

Loving their pride were loath to let you stay

For fear that you might their black deeds excel,

Usurp their seat, and be the prince of hell.

But I believe that you will let your hate 325

O’errule your pride, and you’ll not wish the state

Of governing because your deceived mind

Persuades, your subjects will be womenkind.

But I believe, whenever comes the trial,

Ask but for ten, and you’ll have a denial. 330

You’d think yourself far happier than you be

Were you but half so sure of Heav’n as we.

But when you are in hell, if you should find

More than I speak of, then think heaven designed

Them for a part of your eternal fate 335

Because they’re things which you so much do hate.

But why you should do so I cannot tell,

Unless ’tis what makes you in love with hell,

And, having fallen out with goodness, you

Must have antipathy ’gainst woman, too. [269] 340

For virtue and they so nearly are allied

That none their mutual ties can e’er divide.

Like light and heat, incorporate they are

And interwove with providential care.

But I’m too dull to give my sex due praise; 345

The task befits a laureate crowned with bays.

And yet all he can say will be but small —

A copy differs from the original.

For should he sleep under Parnassus Hill,[37]

Implore the Muses for to guide his quill, 350

And should they help him, yet his praise would seem

At best undervaluing disesteem.

For he would come so short of what they are,

His lines won’t with one single act compare.

But to say truest is to say that she 355

Is good and virtuous unto that degree

As you pretend she’s bad, and that’s beyond

Imagination, ’cause you set no bound.

And then one certain definition is

To say that she doth comprehend all bliss, 360

And that she’s all that’s pious, chaste, and true,

Heroic, constant — nay, and modest, too.

The later virtue is a thing you doubt,

But ’tis ’cause you never sought to find it out.

You question where there’s such a thing or no — 365

’Tis only ’cause you hope you’ve lost a foe,

A hated object, yet a stranger, too.

I’ll speak like you: if such a thing there be,

I’m certain that she doth not dwell with thee.

Thou art Antipodes[38] to that, and all 370

That’s good, or that we simply civil call.

From virtue’s yoke[39] thou hast thy self released,

Turned bully, hector, and a human beast.

That beasts do speak, it rarely comes to pass,

Yet you may parallel with Balaam’s ass.[40] 375

You do describe a woman so that one [270]

Would almost think she had the fiends outdone,

As if at her strange birth did shine no star

Or planet, only Furies in conjunction were,

And did conspire what mischief they should do, 380

Each act his part, and her with plagues pursue.

’Tis false in her, yet ’tis summed up in you.

You almost would persuade one that you thought

That providence to a low ebb was brought,

And that to Eve and Jezebel[41] was given 385

Souls of so great extent, that Heav’n was driven

Into a strait, and liberality

Had made her void of wanting; to supply

These later bodies, she was forced to take

Their souls asunder and so numbers make, 390

And transmigrate[42] them into other, and

Still shift them as she finds the matter stand.

’Tis ’cause they are the worst, makes me believe

You must imagine Jezebel and Eve.

But I’m not Pythagorean to conclude 395

One soul should serve for Abraham[43] and Jude;[44]

Or think that Heaven’s so bankrupt or so poor,

But that each body has one soul or more.

I do not find our sex so near allied

Either in disobedience or in pride 400

Unto the ’bove-named females (for I’m sure

They are refined, or else always pure)

That I must needs conceit[45] their souls the same,

Though I confess there’s some that merit blame.

But yet their faults only thus much infer, 405

That we’re not made so perfect, but may err;

Which adds much luster to a virtuous mind, [271]

And ’tis her prudence makes her soul confined

Within the bounds of goodness, for if she

Was all perfection unto that degree 410

That ’twas impossible to do amiss,

Then Heaven, not she, must have the praise of this.

But she’s in such a state as she may fall,

And, without care, her freedom may enthrall.

But to keep pure and free in such a case 415

Argues each virtue with its proper grace.

And as a woman’s composition is

Most soft and gentle, she has happiness

In that her soul is of that nature, too,

And yields to anything that Heav’n will do, 420

Takes an impression when ’tis sealed in Heaven,

Turns to a cold refusal when ’tis given

By any other hand. She’s all divine,

And by a splendid luster doth outshine

All masculine souls, who only seem to be 425

Made up of pride and their loved luxury.

So great is man’s ambition that he would

Have all the wealth and power if he could

That is bestowed upon the several thrones

Of the world’s monarchs, covets all their crowns. 430

And by experience, it hath been found

The word ambition’s not an empty sound.

There’s not an history which doth not show

Man’s pride, ambition, and his falsehood, too.

For if at any time th’ambitious have 435

Least show of honor, then their souls grow brave,

Grow big and restless; they are not at ease

Till they have a more fatal way to please,

Look fair and true, when falsely they intend —

So from low subject, grow a monarch’s friend. 440

And by grave counsels they their good pretend

When ’tis gilt-poison[46] and oft works their end.

The son who must succeed is too much loved,

Must be pulled down (his counsel is approved)

For fear he willingly should mount his father’s seat. 445

So he’s dispatched, and then all those that be

Next in the way are his adherency.

And then, the better to secure the state, [272]

It is but just they should receive his fate.

So by degrees he for himself makes room. 450

His prince is straightway shut up in his tomb,

And then the false usurper mounts the throne —

Or would do so at least but commonly

He ne’er sits firm, but with revenge doth die,

But thank Heav’n there’s but few that reach so high, 455

For the known crimes make a wise prince take care.[47]

And thus by what I’ve said, we plainly find

That men more impious are than womankind.

So those who by their abject fortune are

Remote from courts no less their pride declare 460

In being uneasy and envying all who be

In state above them, or priority.

But ’tis impossible for to relate

Their boundless pride, or their prodigious hate

To all that fortune hath but smiled upon 465

In a degree that is above their own.

And thou, proud fool, that virtue wouldst subdue,

Envying all that’s good, dost tower o’er women, too,

Which doth betray a base ignoble mind

And speaks thee nothing but a blustering wind. 470

But in so great a lab’rinth as man’s pride,

I should not enter, nor won’t be employed.

For to search out their strange and unknown crimes,

So many are apparent in these times,

My dull arithmetic can never tell 475

Half of the sins that commonly do dwell

In one poor sordid swain;[48] then how can I

Define the court’s or town’s debauchery?

Their pride in some small measure I have shown, 480

But ’tis too great a task for me alone;

Nor yet more possible I should repeat

The crimes of men extravagantly great.

I would not name them but to let them see

I know they’re bad and odious unto me. 485

’Tis true, pride makes men great in their own eyes,

But them proportionable I despise.

And though ambition still aims to be high,

Yet lust at best is but bestiality,

A sin with which there’s none that can compare, [273] 490

Not pride, nor envy, etc., [49] for this doth ensnare

Not only those whom it at first enflamed:

This sin must have a partner to be shamed

And punished like himself. Hold, one won’t do,

He must have more, for he doth still pursue 495

The agents of his passion; ’tis not wife,

That mutual name, can regulate his life.

And though he for his lust might have a shroud,

And there might be polygamy allowed,

Yet all his wives would surely be abhorred 500

And still some common Lais[50] be adored.

Most mortally the name of wife they hate,

Yet they will take one as their proper fate

That they may have a child legitimate

To be their heir, if they have an estate, 505

Or else to bear their names. So for by ends

They take a wife and satisfy their friends

Who are desirous that it should be so,

And for that end, perhaps, estates bestow,

Which, when possessed, is spent another way, 510

The spurious issue do the right betray,

And with their mother-strumpets are maintained;

The wife and children by neglect disdained,

Wretched and poor, unto their friends return

Having got nothing, unless cause to mourn. 515

The dire effects of lust I cannot tell,

But I suppose they’re catalogued in hell,

And he, perhaps, at last may read it there

Written in flames, fierce as his own, whilst here.

I could say more, but yet not half that’s done 520

By these strange creatures, nor is there scarce one

Of these inhumane beasts that do not die

As bad as Bewley’s pox[51] turns leprosy,

And men do catch it by mere fantasy.

Though they seem chaste and honest, yet it doth 525

Pursue them, while they swear it with an oath

’Twas only in company, infected breath

Gave them the plague, which hastens on their death,

Or else the scurvy, or some new disease,

As the base wretch or vain physician please. [274] 530

Then a round sum the surgeon he must have

To keep corruption from the threatening grave,

And then ’tis doubled, for to hide the cheat.

(O the sad horror of debauched deceit!)

The body and estate together go, 535

And then the only objects here below

On which he doth his charity bestow

Are whores and quacks, and perhaps pages, too,

Must have a share, or else they will reveal

What money doth oblige ’em to conceal. 540

Sure trusty stewards of extensive Heaven,

When what’s for common good is only given

Unto peculiar friends of theirs, who be

Slaves to their lust, friending debauchery;

These are partakers of as great a fate 545

As those whose boldness turns them reprobate.

And though a hypocrite doth seem to be

A greater sharer of mortality,

And yet methinks they almost seem all one,

One hides, and t’other tells what he hath done. 550

But if one devil’s better than another,

Then one of these is better than the other.

Hypocrisy preeminence should have

(Though it has not the privilege to save)

Because the reprobate’s example may, 555

By open custom, make the rugged way

Seem much more smooth, and a vile common sin

More pardonable look, and so by him

More take example. ’Tis he strives to win

Mad souls to fill up hell! But should there be 560

Nothing e’er acted but hypocrisy,

Yet man would be as wicked as he is

And be no nearer to eternal bliss.

For he who’s so unsteady as to take

Example by such men, should never make 565

Me to believe that he was really chaste,

And, without pattern,[52] never had embraced.

Such kind of force at best, such virtue’s weak,

That straight with such a slender stress will break,

And that’s no virtue which cannot withstand 570

A slight temptation at the second hand.

But I believe one might as deeply pry [275]

For’t as the Grecian[53] did for honesty,

And yet find none. And then if women be

Averse to’t too, sure all’s iniquity 575

On this side Heav’n, and it with justice went

Up hither,[54] ’cause here is found no content,

But did regardless and neglected lie,

And with an awful distance was passed by.

Instead of hiding their prodigious acts, 580

They do reveal, brag of their horrid facts;

Unless it be some few who hide them, ’cause

They would not seem to violate those laws

Which with their tongues they’re forced for to maintain,

Being grave counselors or aldermen, 585

Or else the wives’ relations are alive,

And then, if known, some other way they’ll drive

Their golden wheels, that way doth seem uneven,

Then the estate most certainly is given

Some other way, or else ’tis settled so 590

As he may never have it to bestow

Upon his lusts, and therefore he doth seem

To have a very high and great esteem

For his pretended joy. But when her friends

Are dead, then he his cursed life defends 595

With what they leave; then the unhappy wife

With her dear children lead an horrid life,

And the estate’s put to another use,

And their great kindness turned to an abuse.

And should I strive their falsehood to relate, 600

Then I should have but Sisyphus his fate,[55]

For man is so inconstant and untrue

He’s like a shadow which one doth pursue,

Still flies from’s word, nay and perfidious, too.

An instance too of infidelity 605

We have in Egypt’s false King Ptolemy,[56][276]

Who, though he under obligations were

To secure luckless Pompey from the snare,

Who fled to him for succor, yet base he

Approved his death, and murderer let go free. 610

He was inconstant, too, or else designed

The same at first, so altered words not mind,

Which is the worse, for when that one doth speak

With a full resolution, for to break

One’s word and oath, most surely it must be 615

A greater crime than an inconstancy,

Which is as great a failing in the soul

As any sin that reason doth control.

But I designed to be short, so must

Be sure to keep confined to what I first 620

Resolved on, or else I should reprove

These faults which first I ought for to remove.

Therefore, with Brutus[57] I this point will end,

Who, though he ought to have been Caesar’s friend,

By being declared his heir, yet it was he 625

Was the first actor in his tragedy.

Perfidious, and ungrateful, and untrue

He was at once — nay, and disloyal, too.

A thousand instances there might be brought

(Not far fetched neither, though more dearly bought) 630

To prove that man more false that woman is,

Far more unconstant, nay perfidious.

But these are crimes which hell (I’m sure not heaven

As they pretend) hath in particular given

Unto our sex — but that’s as false as they, 635

And that’s more false than anyone can say.

All pride and lust, too, to our charge they lay,

As if in sin we all were so sublime

As to monopolize each heinous crime.

Nay, woman now is made the scapegoat, and 640

’Tis she must bear the sins of all the land.

But I believe there’s not a priest that can

Make an atonement for one single man.

Nay, it is well if he himself can bring

An humble, pious heart for th’offering, 645

A thing which ought to be inseparable [277]

To men o’th’gown and of the sacred table.[58]

Yet it is sometimes wanting, and they be

Too often sharers of impiety.

But howsoever the strange world now thrives, 650

I must not look into my teachers’ lives,

But now methinks the world doth seem to be

Naught but confusion and degeneracy.

Each man’s so eager of each fatal sin,

As if he feared be should not do’t again; 655

Yet still his soul is black, he is the same

At all times, though he doth not act all flame

Because his opportunity doth want,

And to him always there is not a grant

Of objects for to exercise his will 660

And for to show his great and mighty skill

In sciences all diabolical.

But when he meets with those which we do call

Base and unjust, why then his part he acts

Most willingly, and then with hell contracts 665

To do the next thing that they should require,

And being thus inflamed with hellish fire,

He yields to anything it doth desire,

Unless ’twere possible for hell to say

They should be good, for then they’d disobey. 670

I am not sorry you do females hate,

But rather deem ourselves more fortunate

Because I find, when you’re right understood,

You are at enmity with all that’s good.

And should you love them, I should think they were 675

A-growing bad, but still keep as you are.

I need not bid you, for you must I’m sure

And in your present wretched state endure:

’Tis as impossible you should be true

As for a woman to act like to you, 680

Which I am sure will not accomplished be,

Till Heav’n’s turned hell, and that’s repugnancy;[59]

When vice turns virtue, then ’tis you shall have

A share of that which makes most females brave,

Which transmutations[60] I am sure can’t be. 685

So thou must lie in vast eternity

With prospect of thy endless misery

When woman, your imagined fiend, shall live [278]

Blessed with the joys that Heav’n can always give.

- The Female Advocate: Fyge’s text, written when she was only fourteen years old, was published as a response to Robert Gould’s misogynist satire Love Given O’er or, a Satire against the Pride, Lust, and Inconstancy etc. of Woman (1682). ↵

- venture: a risk or enterprise that will try one’s fortune; thus the small venture of the Preface might be like a ship sent forth to pass the ocean of critics. ↵

- The first edition of Fyge’s poem was published with a different preface in 1686 and contained errors, which Fyge attributes in the following sentences to the capriciousness of the compositors who set the type of the first edition and in so doing writ what they pleased. Here, she maintains that the first edition was published against her will. ↵

- pass current: pass from hand to hand; circulate, like authentic currency; not counterfeit ↵

- endued: invested or endowed ↵

- votaries: one bound by a special vow, as a nun or monk ↵

- Here and throughout the poem, Fyge addresses her misogynist opponent, Robert Gould. ↵

- sway: control or influence; frequently used to denote sovereign power ↵

- ’Cause . . . alone: See Genesis 2:18 (KJV): “And the Lord God said, It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him an help meet for him.” ↵

- Eve had the command not to eat the fruit at the second hand because Adam, not God, conveyed the admonition to her. ↵

- least charge: less responsibility and therefore blame than Adam ↵

- A reference to the passage in Genesis 3:15, where the curse was read prophetically as the protevangelium foretelling her seed’s (i.e. Christ’s) defeat of the serpent (i.e. Satan). Compare Hutchinson, Order and Disorder 5.62–70 and Southwell, “All Married Men Desire to Have Good Wives,” l. 3. ↵

- The saying was already commonplace when St. Bernard employed it thus: Vulgare proverbium est, quod nimia familiaritas parit contemptum (Scala Paradisi, 8 [PL 40. 1001]). ↵

- And . . . did die: This line quotes from 1 Corinthians 15:22. ↵

- Apollo: Ancient Greek sun god, god of poetry and music, often depicted at the head of the nine Muses. ↵

- incubus: an evil spirit or demon thought to seek sexual intercourse with women while they slept; thus Pluto or Hades, god of the classical underworld, would send such a spirit from hell. ↵

- prodigy: an extraordinary event or thing, such as a comet or freakish creature, thought to be a sign or omen of bad tidings. ↵

- adult’rate: commit adultery against, debauch, debase ↵

- humor: temperament, referring to the doctrine of the humors ↵

- Hymen: ancient Greek god of marriage ↵

- i.e., procreate, or increase in population. ↵

- bawdy-house or nunnery: house of prostitution or nunnery, with perhaps a punning glance at the slang usage of nunnery as a brothel, as in Hamlet’s words to Ophelia: “Get thee to a nunnery!” (3.1.121) ↵

- Livy, 1.57–60, and Ovid, Fasti 2.721–857, both depict the sacrifice of this chaste matron as the founding event of the Roman Republic, at which time kings of Rome, of whom Tarquin was a descendant, met their demise; Shakespeare’s Rape of Lucrece (1594) is a famous Renaissance retelling in narrative verse. ↵

- Witness . . . delight: This story is told by Roger of Wendover in his thirteenth-century chronicle history, The Flowers of History. ↵

- According to classical mythology, the phoenix was the mythical bird resurrected from its own ashes every six hundred years in the Arabian desert. Fyge’s comparison with “Indian women” refers to the Indian custom of “suttee,” whereby widows would let themselves be burned alive on their husbands’ funeral pyres. ↵

- During the siege of Wiensberg by Conrad III in 1140, the women were famously permitted to leave the castle carrying only their most valuable possessions on their backs, while the men were to be executed; the women carried the men on their backs out of the castle, which is still known as Weibertreu (“Women’s Faithfulness”). ↵

- ben’t: a contraction of “be not.” ↵

- Venus-school: the school of the Roman goddess of love; thus probably a reference to a bordello. The practice of ritual prostitution was common in temples dedicated to her and to Aphrodite, her Greek equivalent. ↵

- And if . . . deity: These lines probably alludes to the goddess Venus as she departs from her son, Aeneas, in Virgil’s Aeneid 1.405: “In length of Train descends her sweeping Gown, / And by her graceful Walk, the Queen of Love is known” (trans. John Dryden, 1697, 1.560–61). ↵

- Hesiod, Theogony, depicts the birth of Aphrodite after Cronos castrated Uranus and cast his genitals into the sea; as in Botticelli’s famous Renaissance painting, she was typically represented as rising from the foam fully formed. ↵

- Those . . . no soul: One famous treatise that made this claim was Disputatio nova contra mulieres, qua probatur eas homines non esse (“A new argument against women, in which it is demonstrated that they are not human”), first published in 1595, though reprinted several times throughout the seventeenth century. For a modern edition of this treatise, see Disputatio Nova Contra Mulieres / A New Argument Against Women: A Critical Translation from the Latin with Commentary, Together with the Original Latin Text of 1595, ed. and trans. Clive Hart (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 1998). ↵

- An help for man: echoing God’s explanation for the creation of Eve in the second creation story, Genesis 2:18: “And the Lord God said, It is not good that man should be alone; I will make him an help meet for him” (KJV). ↵

- ignis fatuus: literally, from the Latin, foolish fire; a will-o’-the wisp; a delusive guide ↵

- han’t: a contraction of have not ↵

- bays: a reference to the garland woven of the deep green leaves of the bay laurel, a symbol of poetic acclaim ↵

- Bewley: Bewley was a notorious bawd during Fyge’s time, also mentioned by Gould in Love Given O’er. ↵

- Parnassus Hill: Mount Parnassus in Greece, sacred to Apollo and home to the Muses; therefore a figure for poetic inspiration. ↵

- Antipodes: the opposite side of the globe. ↵

- yoke: a wooden device that holds together two beast of burden, such as oxen, so they can pull a plow or cart; hence, a symbol of discipline or oppression, here used ironically. ↵

- Balaam’s ass: in Numbers 22:28ff., an ass speaks to Balaam after he strikes her; she accuses him of undue cruelty and he thinks she mocks him until he sees an angel of God standing in the way. ↵

- Jezebel makes two relevant appearances in Scripture: in the Hebrew Bible, she is the Phoenician-born queen of Israel who turns King Ahab away from worship of the God of Israel and toward the Phoenician god Baal; she has the prophets of the God of Israel slain, and is eventually killed herself fulfilling a prophecy of Elijah (see 1 and 2 Kings). She is in this connection a general figure of apostasy. In Revelation 2:20, Jezebel is the name of a woman who “calleth herself a prophetess” and seduces God’s “servants to commit fornication” (KJV). ↵

- In the ancient Pythagorean doctrine of metempsychosis, souls would transmigrate from one body to another after death. ↵

- Abraham: biblical patriarch through whom “shall all the families of the earth be blessed” (Genesis 12:3, KJV). ↵

- Jude: the apostle of Christ, whose epistle is the last book of the New Testament before the Book of Revelation. ↵

- conceit: conceive ↵

- gilt-poison: both the first edition of 1686 and the second edition of 1687 read “guilt,” which is a possible pun; but the sense seems more directly related to gilt, or gilded, gold-covered, here used figuratively to refer to the duplicity of bad advice that appears good. ↵

- In the first edition, this and the following two lines form a rhyming triplet: “For the known crimes makes a wise prince take care. / Thus what I’ve said doth plainly shew there are / Men more impious than a woman far.” ↵

- swain: a young man of low social rank ↵

- The first two editions print “&c.” after envy, but “et cetera” is probably not meant to be read aloud as the additional syllables make the line hypermetrical. ↵

- Lais: the name of a famous courtesan from ancient Corinth ↵

- pox: most often in early modern English, the pox signifies venereal disease, particularly syphilis, as the context of lewd behavior here suggests. For Bewley, see n. 36. ↵

- pattern: design or scheme, ulterior motive ↵

- the Grecian: Socrates, who famously sought one honest man and found none but himself willing to admit ignorance; also Diogenes, who sought an honest man. ↵

- and it . . . hither: See Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.150, which represents the departure of the goddess of justice, Astraea, at the onset of the Iron Age: “Piety lay vanquished, and the maiden Astraea, last of the immortals, abandoned the blood-soaked earth” (trans. Frank Justus Miller, ed. J. P. Goold [Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977]). ↵

- Sisyphus his fate: i.e., Sisyphus’s fate, which was, according to ancient Greek myth, repeatedly to roll a boulder up a hill for all eternity ↵

- Ptolemy XIII ordered Pompey to be assassinated on his arrival in Egypt after being defeated at the battle of Pharsalus by the army of Julius Caesar. ↵

- Marcus Junius Brutus was a senator and leading figure of the Roman Republic who orchestrated the assassination of Julius Caesar. Traditionally, his was not the first blow, but the last to strike Caesar dead, as in Shakespeare’s tragedy, Julius Caesar, 3.1; he was, however, the first in rank among the conspirators and therefore the first actor in Caesar’s tragedy. ↵

- men o’th’gown . . . table: i.e. lawyers and ministers ↵

- repugnancy: contradiction, inconsistency ↵

- transmutations: changes, conversions ↵