Pandora, Kneeling

Gillian Knoll

[print edition page number: 235]

I want someone to tell me what to wear in the morning …

I want someone to tell me what to wear every morning. I want someone to tell me what to eat, what to like, what to hate, what to rage about, what to listen to, what band to like, what to buy tickets for, what to joke about and what not to joke about. I want someone to tell me what to believe in, who to vote for, who to love and how to tell them. I want someone to tell me how to live my life, Father, because so far, I’ve been getting it wrong. And I know that’s why people want people like you in their lives, because you just tell them how to do it.

— Fleabag, Fleabag (“Articles of Faith,” season 2, episode 4)

These lines, spoken by the main character of the award-winning Amazon Prime comedy Fleabag, have been posted, pinned, and tweeted many times over (a Google search for the first sentence produces over thirty thousand results).[1] Memorable not only for their content but also for their context, they convey in almost equal measure the protagonist’s disarming vulnerability and a palpable sexual charge. The scene is set in a [236] confessional, the speech addressed to a priest with whom the main character shares an undeniable erotic connection. She is drunk, infatuated with this priest, pleading and tearful by the time she reveals to him what she really wants: “to be told how to live my life, Father … Just tell me what to do, just fucking tell me what to do, Father.” Both a confession and an invitation, Fleabag’s lines draw from the priest a one-word reply that is as startling as it is suggestive: “Kneel.”[2]

“Kneel,” he commands, and she obeys, and a scene that should by all rights amount to little more than a kinky cliché (sex with a priest in a confessional — really?) instantly ensnared the hearts and imaginations of fans and critics. GQ Magazine dubbed it “the greatest moment of TV this year” and “the most erotic use of Catholic imagery since Madonna’s ‘Like a Prayer’ video.”[3] Google reported an uptick in searches for “sex with priest” after the episode aired, and searches on PornHub for “religious” reportedly increased by 162% after the “Hot Priest” was introduced on the series. Articles in mainstream media publications appeared with titles like “The Hot Priest in ‘Fleabag’ Says Kneel, and It’s Never Sounded Sexier” (The New York Times) and “Kneel! How the Whole World Bowed Down to Fleabag … and Her Hot Priest” (The Guardian).[4] I was even able to locate a tote bag for sale on RedBubble with “Kneel?” printed [237] above a photo of Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s face, her eyes turned dreamily upward at the word. Below it, the response reads, “Yes, Daddy.”[5]

Kneel. What can account for the erotic force of this simple word, this single syllable? After the priest issues his mandate once, twice, and a third time, the seconds tick by in silence as Fleabag slowly places her drink on a ledge and descends to her knees. At long last, she looks up and waits … for what? Absolution? Compassion? Direction? The sound of a zipper? The rustling of clerical robes? The possibilities are intentionally tantalizing; but if mainstream representations of sex have trained us to be future-oriented — to dwell on what happens next — a kinky reader knows that it does not matter what the protagonist is waiting for. What she wants, she has already secured: she has been told what to do.

My essay explores the creative potential of this fantasy as it shapes the protagonist of a much different comedy, John Lyly’s The Woman in the Moon (1597). Lyly’s play explores the eroticized experience of being controlled, a vessel, a hollow thing — someone guided, inhabited, even possessed by an outside influence. This is the condition of a (sexual) submissive, a label that has been used broadly to describe someone who finds pleasure in yielding control. Although some submissives (“subs” in kinky parlance) derive pleasure from receiving pain from a Dominant (Dom/Domme), others define their role more generally as a form of erotic receptivity. They might be on the receiving end of any number of bedroom practices (being bound, beaten, humiliated, enslaved, ordered, denied, etc.), but there is no single practice that defines a sub. In this way, submission extends beyond the conventionally “sexual.” As Robin Bauer notes in his ethnographic work on queer BDSM intimacies, “Many partners experienced many erotic practices not directly as sexual, but as creating [238] an erotic atmosphere.”[6] Because this form of kink is less tethered to gender identities or particular sex acts, it can account for forms of intimacy currently undertheorized in queer studies, such as heterosexual intimate relationships with a female sub. My essay’s methodology falls in line with work by scholars such as Melissa E. Sanchez and Joseph Gamble, who propose a queer feminist reexamination of sexual practices and attitudes that might traditionally be perceived as normative, such as heterosexual intercourse. I follow Gamble’s persuasive call to bring “a queer analytic to sexual practice that might seem the furthest thing from ‘queer.’”[7]

Offhand, the premise of John Lyly’s The Woman in the Moon “might seem the furthest thing from ‘queer.’”[8] The play’s central character, Pandora, begins as an unnamed “lifeless image” (1.1.57) that the deity Nature animates at the request of four shepherds who long “to propagate the [239] issue of our kind” (1.1.42).[9] Created to satisfy the desires of men by way of reproductive sex, Pandora might be seen as a heteronormative fantasy incarnate, imbued with a singular purpose: “I make thee for a solace unto men” (1.1.91). To perfect her creation, Nature endows Pandora with gifts from each of the seven planets. But when the planets discover that Nature has stolen their best qualities, their plan for revenge is to dominate Pandora:

Let us conclude to show our empery,

And bend our forces ’gainst this earthly star.

Each one in course shall signorize awhile,

That she may feel the influence of our beams,

And rue that she was formed in our despite.

(1.1.133–37)

Throughout the remainder of the play, each planet takes a turn at filling Pandora with a different ruling passion, from melancholy to madness and mutability, until change itself becomes her defining quality.

Pandora may begin as a heteronormative fantasy, but she quickly embodies a different, kinkier fantasy of utter submission. Lyly’s entire play might be seen as a “what if” scenario analog to Fleabag’s longing to be, in effect, a receptacle. Each of the god-planets dominates Pandora by filling her with their “influence,” and Pandora’s job is, essentially, to take it — more precisely, to feel it, to “feel the influence of [their] beams.” On the one hand, this sounds like the language of the humoral body, filled with liquid passions that govern mood, personality, and behavior.[10] On the other, kinkier hand, this is the language of BDSM, of fantasies that [240] feature a submissive being filled with the ejaculate (“influence,” from the Latin influere, to flow in)[11] of multiple dominant partners. That Pandora is initially created to “propagate the issue of our kind” with four male shepherds (more on Nature’s kinky arithmetic later); that she is essentially used in turn by various Dom/mes who plan to “spot her innocence” (1.1.232) by filling her with their “influences”; that she engages in offstage sexual encounters with every mortal character in the dramatis personae; that her increasingly besotted servant, Gunophilus, spends a good deal of the play breaking the fourth wall to delight in the erotic spectacle Pandora makes of herself: all of this tells a kinky story, the story of Pandora as a sexual submissive. A kinky methodology creates space for this story to run alongside, and to intertwine with, more familiar narratives of early modern cosmology, medieval dramaturgy, and humoral embodiment.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) Online lists the first recorded use of “submissive” in 1974 as a noun designating a sexual identity,[12] and one aim of this essay is to elongate that historical arc by exploring the rich history, in lived experience and in artistic representation, of the sexual submissive as an embodied way of being. Applying the term “submissive” to Pandora’s character — and in general, approaching Lyly’s play with a kinky methodology — illuminates some of Pandora’s most extraordinary and unique features as a character on the early modern English stage. Leah Scragg singles her out because “the rapid shifts of disposition that Pandora undergoes through the influence of the planets make far greater demands on the performer than any other Lylian role,” and Andy Kesson boldly asks, “Does any other character in early modern theatre, or even [241] in theatre full stop, have this much bodily fun?”.[13] The language and conventions of BDSM can function like a grammar that shapes, and helps us trace, the eroticism that runs through the scenes of Pandora’s domination. BDSM also recasts what might be seen as an utterly passive condition as a submissive’s art, and craft, of eroticized feeling. As the planets “bend [their] forces ‘gainst” her, Pandora skillfully bends back. She bends so consummately under the control of each planet throughout the play that she outdoes them, effectively beating them at their own game.

If a Dominant controls the “what” of a scene, a submissive’s skill is to modulate the “how.” Lyly’s play follows this script, with the planets dictating “what to like, what to hate, what to rage about,” but Pandora dictating how she likes, hates, and rages: “how to live my life,” in Fleabag’s words. Pandora’s “how” is utterly constitutive of her character in The Woman in the Moon, a play that dramatizes the process of identity formation by exploring the various roles of nature and nurture, matter and form, in the creation of a self or character. In the end, Pandora finally has a chance to choose her own future course, but even before act five, she develops a sense of self through her experiences as a submissive, an identity based on the mythos from which she takes her name. Pandora, all-gifted, turns out to be a virtuoso in receiving gifts. Submissives are the ones who “take it” in a sexual encounter, and Pandora is no exception. But her example helps us see that taking it can be a gift, a form of self-giving that is also self-making.

Scene Setting

Much has been made of how practitioners of BDSM or “kink” are admirably practised in a forthright, explicit, pragmatic approach to [242] consent … The risk is that these boundaries — assertions of what we want and who we are — become a fixed part of oneself, rather than a strategic stance; that they begin to settle and harden, when one of the pleasures of sex is precisely its changeability, its ability to unfold in ways unpredictable to us; our own capacity to end up somewhere we had not expected.

— Katherine Angel, Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again:

Women and Desire in the Age of Consent

A BDSM scene is set through explicit negotiations between play partners, but Pandora hardly ever speaks or acts on her own in The Woman in the Moon. As Kesson observes, “Every utterance and action Pandora makes between her first speech and the final scene is made under the direction of one of the god-planets.”[14] Perpetually intoxicated with planetary moodiness, Pandora clearly cannot consent to her treatment in the play. Her lack of consent makes Pandora’s situation crucially different from that of a submissive partner in a BDSM encounter. What makes Lyly’s play kinky is not its faithful replication of a real-world BDSM relationship (whatever this might look like in its various premodern or modern configurations) but instead its commitment to unrealness. The Woman in the Moon is, at its core, a creation myth. Aestheticized, fantastical, sometimes hyper-theatrical, Lyly’s play dramatizes a mythology of how a submissive might come to be: the qualities with which the gods fill her, the way she receives and manifests them, the skill she cultivates through various erotic encounters, and the way she experiences the world — or, in Pandora’s case, the cosmos.

Pandora suffers a universe of feeling throughout the play, and Lyly takes great pains to present this universe as fictive. His protagonist exists out of time and place (the play is set in Utopia, literally, “no place”), and [243] she is dominated not by the staffs and crooks of four mortal shepherds but by the gauzy influences of gods. Even Lyly’s dramaturgical style is somewhat out of time. Scragg notes that the play appears “to revert to a style of dramaturgy already outdated when the play was composed.” The divided stage, in which a higher sphere is devoted to supernatural beings and a lower sphere features mortals, along with a host of other features, “point to an emblematic representation of experience in terms of a series of ‘shows’, at one with the procedures of early Tudor drama.”[15] The cumulative effect of this “emblematic representation” is something along the lines of a BDSM scene, bounded and discrete, artful and contrived. Because Lyly’s play is bounded not so much by its place or genre as fictiveness, we can approach it as a fantasy that invites us to read with and for pleasure[16] and to toggle between now and then, tracing erotic connections that do not always obey the spatial-temporal logics of either historicism or presentism. Taking my cue from Lyly’s play, I too thread together different “series of ‘shows,’” arranging them side by side to see how they play — play with and off each other. The robust form of The Woman in the Moon, with its sequence of emblematic representations that explicitly invite us to interpret them (to read both “into” and across) frees us to explore the critical pleasures of identification and resemblance, coincidence and resonance. Not least among these pleasures is noticing Pandora and Fleabag, centuries apart, kneeling and waiting.

First up in Lyly’s aestheticized “series of shows” is Nature’s display of dominance, wherein Lyly goes full bore with the kinky quality of the power imbalance in the scene of Pandora’s making. Gazing proudly on her creation, Nature recalls her plan “to make it such as our Utopians crave” (1.1.59), affirming Pandora’s status as an “it,” an object of “crav[ing].” The scene of Pandora’s “quickening” (1.1.68) has the appearance of a BDSM tableau — probably not the sort of “emblematic representation” Scragg had in mind when she described the play’s dramaturgy, but emblematic all the same. As Nature prepares to imbue the image with “life and soul” (1.1.67), she instructs her two handmaidens, Concord and Discord, to

hold it fast, till with my quickening breath

I kindle seeds of sense and mind.

(1.1.68–69, my emphasis)

The implied stage directions suggest that each handmaiden holds the lifeless Pandora with force (“fast”), perhaps one on each side of her, while Nature brings her lips to Pandora’s to “kindle” her/its “sense.”[17] While it is impossible to pin down exactly what transpires between creator and creation in this exchange, it is clear that Nature displays her dominance as she kindles Pandora, who is at once frozen in a submissive pose, bound and utterly receptive, a vessel of pure feeling.[18]

Apparently Nature has feelings of her own; certainly she relishes her power to enkindle. If Pandora, all-gifted, is defined by her seemingly infinite capacity to receive, Nature might be as readily defined by her aggressive manner of giving: [245]

Thou art endowed with Saturn’s deep conceit,

Thy mind as haught as Jupiter’s high thoughts,

Thy stomach lion-like, like Mars’s heart,

Thine eyes bright-beamed, like Sol in his array,

Thy cheeks more fair than are fair Venus’ cheeks,

Thy tongue more eloquent than Mercury’s,

Thy forehead whiter than the silver Moon’s.

Thus have I robbed the planets for thy sake.

(1.1.95–102)

Nature cannot sustain for long the equanimity of her balanced similes (“as haught as,” “lion-like, like Mars’s heart”). Carried away by her display of power, she finally boasts that she has “robbed the planets” of their gifts in an effort to make Pandora greater — “more fair,” “more eloquent,” and even “whiter” — than her unwilling benefactors. Lyly’s play here installs whiteness among its cosmic superlatives, blanching even Pandora’s “bright” eyes and “fair” cheeks in its pallid hue.[19] Thus “endowed” with this dazzling array of properties and powers, Pandora is nonetheless soon reminded of her subservience to the deity’s demands: “see thou follow our commanding will” (1.1.92).

Nature’s “commanding will” exposes her kinky bent even before the queer erotic charge passes between the two female characters during Pandora’s “quickening.” The deity sets an ensnaring scene for Pandora, binding her into a thick web of desires remarkable not only for their volatility but for their sheer quantity. Nature’s kinky arithmetic, what with its 4 lovelorn shepherds 1 infatuated servant 7 affronted gods, [246] also reveals the Dommey (sometimes sadistic) potential embedded in the playwright’s own scene setting. The creation deity is repeatedly conflated with Lyly in the opening scene, where Nature is “author of the world” (1.1.31), “author of all good” (1.1.87), and “author of your lives” (1.1.123). Why does Pandora’s “author” (Lyly? Nature? Or both?) create such a stark imbalance, and why does no character in Lyly’s play call attention to it? It is assumed that the four shepherds will duke it out for Pandora’s affections, but it is difficult to puzzle out any vanilla reason behind this odd calculus, especially because we learn early on that Nature has been crafting several images in her workshop. Lyly’s stage directions indicate that curtains are drawn to reveal “Nature’s shop, where stands an image clad, and some unclad” (1.1.56.1). Why does Nature surround Pandora with naked “images” (paintings? sculptures? actors?) but not kindle three more of them to join Pandora as mates for the remaining shepherds? Queer studies of early modern literature and culture have, as we would expect, made a case for nature’s queerness, and Lyly’s play falls in line with much of this important work.[20] But The Woman in the Moon makes a compelling case that Nature is kinky, too.

Topping from the Bottom

Submission, I soon learned, was also a kind of power … I had a choice, a craft, whether he ascends or falls depends on my willingness to make room for him, for you cannot rise without having something to rise over. Submission does not require elevation in [247] order to control. I lower myself. I put him in my mouth, to the base, and peer up at him, my eyes a place he might flourish. After a while, it is the cocksucker who moves. And he follows, when I sway this way he swerves along. And I look up at him as if looking at a kite, his entire body tied to the teetering world of my head.

— Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous

Kneel. For the protagonist of Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, this is a self-reflexive [250] act: “I lower myself.” Vuong’s novel tells a complex story of action and passion, doing and being, and among the most arresting features of that story is the expansive verticality of the kite image. By kneeling so low, Vuong’s protagonist makes his Dom soar. There is something about the submissive’s groundedness, the “teetering world” he makes of his head, that frees the Dom to stretch infinitely upward. Peering down at the submissive’s eyes, the Dom finds more than a mere reflection of himself — he finds “a place he might flourish.”[21] Pandora becomes such a place for the god-planets, an “earthly star” (1.1.135) that reflects their best qualities but also makes each of them glow more brightly. Like the protagonist of Vuong’s novel, Pandora adopts the set of practices known in the kink community as “topping from the bottom.” The Woman in the Moon’s vertical economy makes this practice uniquely visible; dramaturgically, the planets sit on high and gaze down on Pandora until the end, when she ascends to the top, taking her place in the moon. But Pandora tops from the bottom in other ways, too. Ontologically, she is characterized by her receptivity to planetary influence, yet she outperforms those planets at various points in the play. Dramatically, she holds all the power; like Fleabag’s kneeling protagonist, whom the camera almost never leaves, Pandora’s submission takes center stage throughout the play. And sexually, although Pandora is defined by her receptivity, we see her aggressively beat one suitor, bed down three others [248] in quick succession, and flip some of the scripts the god-planets write for her.

The first two planets script Pandora as a receptacle to “fill” (2.1.3), but in both scenes, she bursts with feeling — and in both scenes, she brings others to their knees. While Saturn plans to inflict a “melancholy mood” (1.1.144) that makes her “self-willed and tongue-tied” (1.1.149), Pandora reacts with eloquence and precision, giving a voice to her supposedly “tongue-tied” melancholy:

What throbs are these that labour in thy breast?

What swelling clouds that overcast my brain?

I burst unless by tears they turn to rain.

(1.1.171–73)

Pandora’s action verbs — throbs, swelling, overcast, burst — characterize her less as a container than as a conduit who overflows with feeling. When at last, her melancholy does silence her, Pandora’s stage action speaks volumes. Perhaps Lyly’s most memorable stage direction is the delightfully ambiguous “she plays the vixen with everything about her” (1.1.176.1), which Scragg glosses as “acts shrewishly, ill-temperedly.”[22] Kesson writes of this “extremely unusual” turn of phrase, “Once again, the play hands over decision-making to its performer, and asks them to go crazy.”[23] Perhaps it is the actor’s virtuosic improvisation that draws from the four besotted shepherds their own dramatic display of supplication. Showering her with praises, they “all kneel to her” (1.1.184.1). She, in turn, “hits [Stesias] on the lips” (1.1.188.1) and “strikes [Learchus’s] hand” (1.1.194.1). Pandora’s aggression here is a virtuosic expression of her submission to Saturn. She follows his script to the letter, since her “self-will” is what drives her “tongue-tied” stage actions, but she also exceeds this script. Effectively gagged, Pandora discovers a new improvisational [249] language of striking, hitting, and playing the vixen — of topping from the bottom — through which she absorbs and owns the melancholic feeling he imparts.

Lyly explores the sexual power of this aggressive receptivity in the following scene, in which Jupiter initially describes Pandora as a vessel, comparing her to his other conquests: “in this one [Pandora] are all my loves contained” (2.1.18). As soon as he confronts Pandora, however, Jupiter changes his tune and figures himself beneath her, claiming to be

High Jove himself, who, ravished with thy blaze,

Receives more influence than he pours on thee,

And humbly sues for succour at thy hands.

(2.1.24–26)

If Pandora spends much of the play topping from the bottom, here we see “High Jove” bottoming from the top, even capitulating to Pandora’s demand to “give me thy golden scepter in my hand” (2.1.41) and finally fleeing the scene altogether in fear of “jealous Juno” (2.1.80). When Pandora redirects her newfound power toward her servant Gunophilus, she plays with scripts and postures familiar within BDSM scenes, commanding the “base vassal” to

honour me with kneel and crouch,

And lay thy hands under my precious foot.

(2.1.85–87)

More important than this display of power is the pleasure it apparently affords Pandora. When Gunophilus confesses his “feeble[ness]” and “holy fear” of her, she answers, “thou pleasest me” (2.1.100); then, receiving the four doting shepherds, “I please myself in your humility” (2.1.145). Pleasure was never on the menu when Jupiter began his reign; he planned only to “fill her with ambition and disdain” (2.1.3). Pandora’s self-reflexive declaration, “I please myself,” signals her conversion of the planets’ proprietorship into pleasures entirely her own. Like Vuong’s “I lower myself,” Pandora is both subject and predicate, top and bottom, finding in submission not only “a kind of power,” but a kind of pleasure, too.

Slut Training

Slut training is a BDSM process where a dominant partner teaches the consenting submissive partner to behave in a sexually unrestricted or “slutty” way … It ideally results in a holistic transformation involving what they wear, how they act, and how they think.

— “Slut Training,” Kinkly.com

Great sluts are made, not born.

— Janet W. Hardy and Dossie Easton, The Ethical Slut

While many BDSM rituals intensify the hierarchies that separate a Dominant from their submissive, “slut training” is a murkier, boundary-blurring practice. How does the teacher hold onto the reins when they are instructing their student to “be loose” (3.2.66), to use Pandora’s phrase? And how does anyone teach “sexually unrestricted” behavior in the first place? Scholars like Valerie Traub and Gamble have argued persuasively that sexual knowledge is not like other kinds of knowledge because, as Traub writes, “there is much about sex that we don’t know: of what acts sex consists, what pleasures it affords, what difficulties it encounters, and what inventiveness it engenders.”[24] Slut training is thus a somewhat opaque pedagogical encounter (e.g., defining “sexually unrestricted” behavior — unrestricted from what, exactly?), and if the teacher does [251] their job well, the student’s erotic “inventiveness” might soon take them both off book.

Perhaps this is why Venus confines herself to a relatively simple script when she ascends in act three of The Woman in the Moon. “I’ll have her witty, quick, and amorous,” she declares,

Delight in revels, and in banqueting,

Wanton discourses, music, and merry songs.

(3.2.2–4)

The love goddess takes a hands-off approach to slut training (Venus is one of the few characters whose hands are not on Pandora in this scene). She sketches the “what,” but leaves it to Pandora to manifest the “how.” How, for example, might Pandora embody Venus’s “amorous[ness],” a supple word that leaves room for improvisation, as Jeffrey Masten has shown in his research on the word’s active and passive connotations in the OED? To be amorous might mean that Pandora is (actively) “inclined to love,” but also that she is (passive) “loveable, lovely,” a condition already woven into her identity as a purpose-built love object.[25] If Pandora has been passively amorous from the start of the play, the experience of slut training licenses her to lean into this condition — to “incline” actively.

Venus does not so much write a script, then, as create conditions that quicken Pandora’s kinky inventiveness and improvisation. She frames her control over Pandora as a kind of enforced freedom. “Let her to the world” (3.2.18), Venus proclaims, and in response Pandora falls in love with the world — or at least, all the people in it. She woos her servant Gunophilus (“I am lovesick for thee” [3.2.83]) and seduces all the shepherds except Stesias, whom she married in the previous scene, but now asks herself, “Must I be tied to him? No! I’ll be loose” (3.2.66). [252] Thus loosened, Pandora embodies Venus’s “witty, quick, and amorous” in her own way — by becoming singularly bossy. Observing that the shepherds “look like water nymphs” (3.2.148), she emasculates each of them in turn, comparing one to “Nature in a man’s attire” (3.2.149), then another to “young Ganymede, minion to Jove” (3.2.150). Robbing her suitors of any opportunity to woo her, she devotes herself to orchestrating what Kesson calls “a six-person sex free-for-all.”[26] Not sex but Pandora’s sexual dominance is everywhere present in the scene, even at the level of language. Rarely figuring herself as passive in her offstage sexual escapades, she takes charge of each action verb:

Now have I played with wanton Iphicles,

Yea, and kept touch with Melos. Both are pleased.

Now, were Learchus here! But stay, methinks

Here is Gunophilus. I’ll go with him.

(3.2.224–27)

Venus may rule on high, but Pandora rules on the ground, to the extent that her sexuality can take a violent turn:

Thus will I hang about Learchus’ neck,

And suck out happiness from forth his lips.

(3.2.257–58)

When Pandora is not engaging in offstage sexual rendezvous, she is busy organizing them, an activity that appears to offer its own pleasures. First she arranges to meet each shepherd separately — “Meet me in the vale” (3.2.156), “go to yon grove” (3.2.169), and so on — but then she coordinates a banquet where her lovers can fight over her. She sets the time and place, she orders Gunophilus to manage various details, and she navigates [253] the tense conversation among her jealous lovers in a series of asides (“Knows not Melos I love him?” [3.2.299] she whispers to one, then to another, “Hath Iphicles forgot my words?” [3.2.301]). Scragg has called this “the most intricately plotted scene in the Lylian corpus,”[27] and it would seem that this distinction owes something to Lyly’s kinky collaborators. Who is doing the plotting? Within the scene’s fiction, “banqueting” (3.2.3) is Venus’s design, but the “how” of the banquet belongs to Pandora, who carefully caters it onstage and thus exceeds the fiction, bending it to her self-will. Lyly’s script depends on Nature’s, hers depends on the planets’, the planets’ on Pandora’s improvisational art. Apparently this “most intricately plotted scene” is the work of many kinky minds and hands, its pleasures and powers diffused and distributed among Dom/mes and sub alike.

If Venus’s mode of “slut training” looks familiar, it is because we have already seen it in the play’s opening scene. Venus’s art reflects Nature’s own art of scene setting, of creating conditions, of binding in order to loosen. Pandora’s Dommes set the parameters — Nature’s kinky math, Venus’s scripted “banqueting” — but they leave it to her to activate the potential eroticism within the scene. That Pandora decides to invite all her lovers to a banquet right on the heels of her private sexual trysts with each one (and with her servant) suggests that she shares in the pleasures of Nature’s kinky math. That she wants to “entertain” (3.2.237) multiple lovers at once suggests that intricate plotting affords its own erotic delights, as Venus, Nature, and evidently Lyly himself all know. Such pleasure may not align with the stereotype of a slavish, passive submissive, but Pandora’s submissiveness is defined by responsiveness, not slavishness, by a capacity to take what she is given, absorb it, and make it her own. [254]

Subspace

It can look so many ways … almost like being both

in yourself and outside yourself simultaneously.

— Quinn B., kink educator and founder of

Unearthed Pleasures, “A Beginner’s Guide to Subspace”

By the time Pandora is subjected to Luna’s influence, she has been dominated by six planets and given herself up to an impressive range of passions: melancholy, disdain, anger, gentility, lust, and duplicity. When the moon goddess ascends, she promises to add to this list “Newfangled, fickle, slothful, foolish, [and] mad” (5.1.5). In some respects, Luna’s script for Pandora is a rehash of Lyly’s; one gets the sense that Pandora has been auditioning for this role from the start of the play. But if she contains multitudes in acts one through four, those multitudes multiply in act five, in which Pandora’s mood changes as quickly as her mind:

Where is the larks? Come, we’ll go catch some straight!

No, let us go a-fishing with a net!

With a net? No, an angle is enough.

An angle? A net? No, none of both.

(5.1.25–28)

Luna’s script reduces Pandora to a creature of want; Pandora can hardly pronounce one object of her desire before the next one claims her. The men around her describe Pandora as “lunatic” (5.1.69, 93) “foolish” (5.1.120, 136), and “stark mad” (5.1.191), but a kinky reader might descry in what Scragg calls Pandora’s “sexually laden stage raving”[28] something akin to “subspace.” [255]

Not all submissives experience subspace, and those who do characterize it so variously that it escapes easy definition, but kink educator Quinn B.’s broad description of “being both in yourself and outside yourself simultaneously” captures many of its flavors.[29] For some submissives, subspace is a state of high suggestibility and vulnerability, a psychic space as much as a material one. Some describe it as a metaphysical state, “a kind of profound and divine loss of self.”[30] For others, subspace is more of a physical condition induced by pain and characterized by an increased pain tolerance. Some submissives describe it as a high, an intense euphoria often followed by “sub-drop,” a depleted state that has been associated with a reduction of adrenaline, oxytocin, and serotonin.[31] Not all of these accounts fit Pandora’s situation, but the play’s descriptions of Pandora’s altered state (e.g., Gunophilus’s “What a sudden change is here!” [5.1.22]) present an opportunity to reflect more closely on what it is that Luna does to Pandora. In subspace, a submissive is likely to crave more — more of whatever constitutes their submission, more pain or humiliation, more restrictions or commands, or more intense edgeplay or roleplay. And under Luna’s sway, Pandora manifestly wants more. Her desires are remarkable both for their plasticity (an angle! no, wait — a net!) and their abundance:

But shall I have a gown of oaken leaves,

A chaplet of red berries, and a fan

Made of the morning dew to cool my face?

How often will you kiss me in an hour, [256]

And where shall we sit till the sun be down?

(5.1.35–39)

She wants so much and so many, articulating each desire in such fine-grained detail that we can hear how she anticipates Fleabag’s “I want someone to tell me what to eat, what to like, what to hate, what to rage about, what to listen to, what band to like, what to buy tickets for, what to joke about and what not to joke about.” For both Fleabag and Pandora, their objects of desire, though carefully specified, matter less than the attendant affect, the posture, and the condition of wanting.

Subspace is intoxicating, and Pandora’s inebriated state leads her to pursue her desires aggressively. Still, the overall effect is one of submission. Pandora inarguably submits to Luna, as she submitted to the other planets, but here she seems mostly enslaved to her own whims. Moreover, her language and behavior comport with accounts of subspace by BDSM practitioners who describe it as an altered state of consciousness. “I get high”; “You end up in this incredibly strong rush so you just don’t have control anymore”; “It is almost that I lose consciousness. Not that I get tired but I give up.”[32] Under Luna’s domination, Pandora’s final stage direction is “Dormit” (5.1.209.1). One gets the sense that her slumber is a mix of giving up and giving in. Pandora sleeps through about fifty lines of angry dialogue among her jilted lovers, who are at the point of killing her when the planets finally intervene, at which point “She awakes and is sober” (5.1.258.1).

It is easy to imagine that Pandora’s drunken slumber is a way of tapping out, of removing herself from the intensity of Luna’s domination (and her lovers’ violent display). But when Nature returns to the stage and allows her creation finally to choose which “one of [the planets’] [257] seven orbs … she shall be placed in” (5.1.276), Pandora settles on Luna, “the lowest of the erring stars” (5.1.2). There is something about subspace, apparently, that draws Pandora back: “it content[s] me best” (5.1.315). Her final choice of the play is to become at turns “idle, mutable, / Forgetful, foolish, fickle, frantic, mad” (5.1.313–14), in short, to abandon herself to each new feeling that strikes her. She has been doing this all along, but in freely choosing submission (“awake and sober”), Pandora embraces the constitutive and creative power and pleasure of receptivity.

Pandora, Kneeling

Perhaps this was everything: thus to kneel … : to kneel: and thereby hold one’s own outward willing contours tightly reined

— Rainer Maria Rilke, “The Donor”[33]

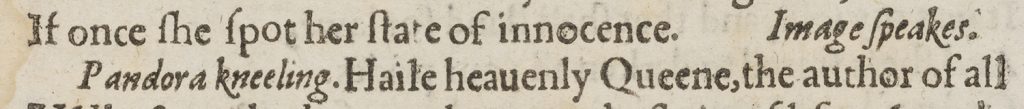

Lyly’s stage directions call for Pandora to kneel only once in The Woman in the Moon, during the scene of her creation. Kneeling is her third scripted stage action of the play, but it is the first thing she does under the speech prefix “Pandora” in Lyly’s quarto. Until she kneels, she is only “the Image,” and until she kneels, “the Image” is rather unsteady. Her first scripted action, after Nature decides to “let her stand, or move, or walk alone” (1.1.77), reads, “The image walks about fearfully” (1.1.77.1). Kesson singles this out as “an unprecedented early modern stage direction, a cue for a player to walk as a new creature in a terrifying world.”[34] Pandora begins the play with the freedom of motion, with a menu of options for how to comport herself and make her way in the world. For how long does Pandora’s “fearful” stage business persist? It might go on for [258] as many as ten lines of dialogue, until Nature commands her handmaid Discord to “unloose” Pandora’s “tongue, to serve her turn” (1.1.83), which prompts Lyly’s next set of stage directions (figure 9.1): “Image speakes,” and then, “Pandora kneeling” (1.1.86–87.1).

Given a voice “to serve her turn,” Pandora uses it to serve her author. And then she kneels, a gesture of submission that serves Pandora too. Kneeling seems to gather her, to “hold [her] own outward willing contours tightly reined,” in Rilke’s words. In choosing to lower herself, to draw herself in, Pandora takes shape and earns her name.

Kneeling is not an altogether atypical response to what we might call an existential crisis, Pandora’s sudden awareness (she talks of her “understanding soul” [1.1.89]) of herself as a created being. Across time and place, another character who undergoes a similar crisis is Fleabag. Among Fleabag’s many struggles is a peculiar metaphysical quandary that grips her in the episodes with the priest, involving her status as a fictional character. As she becomes more intimately connected with the priest, the wry asides she has been delivering to camera throughout Fleabag suddenly and alarmingly open themselves to the priest’s ears. Surely this new development heightens her awareness of her condition as a created being who answers to an “author” of one kind or another.[35] And this awareness draws her almost magnetically toward the priest, [259] someone with the power to see and hear her, to “tell [her] what to” do. It is what brings her to her knees.

Rilke’s poetic conceit of kneeling as self-binding would likely resonate with many submissives. Bondage, and even pain, can define a person by making them feel their shape, sharpening their edges, and creating sensation at the body’s contours, whether in the push back against restraints or in the sting of flesh. Imani Davis’s poem “Kink” speaks to this shaping power:

I never thought restraint would be my thing.

Then you: the hole from which my logic seeps,

who bucks my mind’s incessant swallowsong

& pins the speaker’s squirming lyric down

with ease.[36]

For Davis and their “Kink,” bondage is what imparts a “measured” iambic form on their “squirming lyric”; it wraps

knuckles tight around

a bratty vers.

It is a kind of kneeling, a pinning down and gathering in. If The Woman in the Moon is not kinky in any other way, it is at least kinky in this, its form. It is John Lyly’s only play written in verse, and at its center is a brat.[37] [260]

I don’t think Lyly’s verse restrains bratty Pandora in quite the way Davis imagines the poetic form containing their “bratty vers.” Pandora never kneels in her final scene (in fact all of the mortal characters have knelt before her by this point in the play, to her palpable delight) but neither does “the Image walk … fearfully.” Something gathers Pandora when she is at last given the opportunity to choose her own course, because when she settles on Luna, she declares that

change is my felicity,

And fickleness Pandora’s proper form.

(5.1.307–8)

Like Davis’s speaker, Pandora locates her pleasure — her “felicity” — in having a “proper form.” But for Pandora, that form is fluid and “mutable” (5.1.313). What gives her shape is receptivity, her desire and capacity to feel.

If Lyly’s play is a mythology of a sexual submissive, it might also be a story of anyone who has found pleasure in feeling influence. As Katherine Angel writes, “Relationality and responsivity characterize all human interactions, whether we admit it or not …. Why consider as a flaw the act of yielding, the fact that we are susceptible to others? Feelings, sensations, and desires can lie dormant until brought into being by those around us.”[38] In Pandora’s character and situation, Lyly stretches Angel’s “relationality and responsivity” to a cosmic extreme. This is what kink offers us in its extremes — the ability to see with a magnifying glass the subtle eroticism in gestures, postures, and language that we encounter every day. In the fleeting, inexplicable rush of sensation we can feel from an exceptionally good hug, for example, we might sample the pleasures and freedoms of being bound to the bedframe. As Karmen MacKendrick writes, [261]

All one can do is to give oneself over to pleasure, and it will take one beyond oneself, or not. In this giving over, the distinctions between “normal” and “perverse” pleasure begin as differences of degree, or more clearly of intensity, and this intensification at some level becomes indistinguishable from a difference in kind.[39]

Such differences seem sharply drawn in The Woman in the Moon, with its mythological context and its cosmic cast of characters, but MacKendrick makes the case that they coalesce in the act of “giving over” to pleasure. Giving over: this is Pandora’s submissive art, itself a source of pleasures both strange and familiar. Lyly’s origin story locates such pleasures in our aptitude for yielding to the force of another body — in the act of leaning (even for an instant) into a too-tight embrace, of softening against a hard edge and being shaped by someone else’s desire. For Pandora, the moon is just such a shaping force that helps to “hold one’s own outward willing contours tightly reined,” even as those contours shift and change.

- Google search completed on October 12, 2023. ↵

- Fleabag, season 2, episode 4, “Articles of Faith,” directed by Harry Bradbeer, written by Phoebe Waller-Bridge, aired March 25, 2019, https://www.amazon.com/gp/video/detail/B0875FRLWQ, 00:24:09. ↵

- David Levesley, “Andrew Scott Talks Us Through Fleabag’s ‘Kneel’ Scene,” British GQ Magazine, September 4, 2019, https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/men-of-the-year/article/andrew-scott-fleabag-kneel. ↵

- See Kathryn Shattuck, “The Hot Priest in ‘Fleabag’ Says Kneel, and It’s Never Sounded Sexier,” The New York Times, May 17, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/17/arts/television/fleabag-andrew-scott-hot-priest.html; and Laura Snapes, “‘Kneel! How the Whole World Bowed Down to Fleabag … and Her Hot Priest,” The Guardian, December 23, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/dec/23/kneel-how-the-whole-world-bowed-down-to-fleabag-and-her-hot-priest. Results from Pornhub and Google searches are reported in Snapes, “‘Kneel’!.” ↵

- Please buy this tote bag: fleabagmemes, “FLEABAG Kneel. Yes, Daddy. Tote Bag,” Redbubble.com, accessed December 14, 2022, https://www.redbubble.com/i/tote-bag/FLEABAG-Kneel-Yes-Daddy-by-fleabagmemes/66533522.A9G4R. ↵

- Robin Bauer, Queer BDSM Intimacies: Critical Consent and Pushing Boundaries (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 48. Bauer also explores this subject from a phenomenological perspective, which defines “desire as reaching out toward the world with one’s body” (49). ↵

- Joseph Gamble, “Practicing Sex,” The Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 19, no. 1 (2019): 85–116, at 94, https://doi.org/10.1353/jem.2019.0013. See also Melissa E. Sanchez, “‘Use Me But as Your Spaniel’: Feminism, Queer Theory, and Early Modern Sexualities,” PMLA 127, no. 3 (2012): 493–511, https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2012.127.3.493. ↵

- Prior to queer studies of Lyly over the past two decades, most scholarship on Lyly’s corpus was decidedly straight and vanilla, focusing on political allegory and prose style. I am delighted to be contributing to a queer/kinky renaissance in Lyly criticism, most of which has focused on his play Galatea. See for example Valerie Traub, The Renaissance of Lesbianism in Early Modern England (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002); Simone Chess’s Male-to-Female Crossdressing in Early Modern English Literature: Gender, Performance, and Queer Relations (New York: Routledge, 2019), 138–66; and the pioneering work on Galatea by Andy Kesson and Emma Frankland, “‘Perhaps John Lyly Was a Trans Woman?’: An Interview about Performing Galatea’s Queer, Transgender Stories,” The Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 19, no. 1 (2019): 284–98, https://doi.org/10.1353/jem.2019.0048. My own book explores queer forms of eroticism in Lyly’s dramatic corpus. See Gillian Knoll, Conceiving Desire: Metaphor, Cognition, and Eros in Lyly and Shakespeare (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020). ↵

- All citations of Lyly’s The Woman in the Moon are from John Lyly, The Woman in the Moon (The Revels Plays), ed. Leah Scragg (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2006). Parenthetical citations refer to act, scene, and line number. ↵

- Gail Kern Paster describes humoral bodies as “earthly vessels defined by the quality and quantity of liquids they contain” (6). See Gail Kern Paster, Humoring the Body: Emotions and the Shakespearean Stage (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004). ↵

- See Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “influence, n.,” September 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1751993208. ↵

- Entry B2b under “submissive, adj. and n.” reads, “A person who plays the submissive role in (sadomasochistic) sexual activity.” (The earliest example is from M. M. Hunt’s Sexual Behavior in 1970s [1974]). Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “submissive (adj. and n.),” July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/2537623946. ↵

- See Leah Scragg, introduction to John Lyly, The Woman in the Moon (The Revels Plays), ed. Leah Scragg (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2006), 34; and Andy Kesson, “The Women in the Moons,” Before Shakespeare (blog) March 10, 2018, https://beforeshakespeare.com/2018/03/10/women-in-the-moons/. ↵

- Andy Kesson, “‘It is a pity you are not a woman’: John Lyly and the Creation of Woman,” Shakespeare Bulletin vol. 33, no. 1 (2005): 33–47, at 41–42, https://doi.org/10.1353/shb. 2015.0001. ↵

- Scragg, introduction to The Woman in the Moon, 15–16. ↵

- A kinky methodology also engages in the kind of reparative reading practice that Christine Varnado calls for at the end of Shapes of Fancy, in which critics acknowledge “the seeking of pleasure, both as an end in itself and as an intrinsic element of knowledge production, in relation to texts” (259). See Christine Varnado, Shapes of Fancy: Reading for Queer Desire in Early Modern Literature (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2020). Varnado draws from Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading: Or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Introduction Is about You,” in Novel Gazing: Queer Readings in Fiction, ed. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (Durham, NC, and London, UK: Duke University Press, 1997), 1–40. ↵

- For punning connotations of “sense,” see Angelo’s aside in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, when he is overcome with lust for Isabella: “She speaks and ’tis / Such sense that my sense breeds with it” (2.2.141–42). Cited from William Shakespeare, Measure for Measure (The Pelican Shakespeare), ed. Jonathan Crewe (New York, NY: Pelican Books, 2017). ↵

- See Colby Gordon, “A Woman’s Prick: Trans Technogenesis in Sonnet 20,” in Shakespeare/Sex: Contemporary Readings in Gender and Sexuality, ed. Jennifer Drouin (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 269–89, for an analysis of Shakespeare’s “transfeminine version of the creation myth” (273), another mythology “governed by an infatuated Nature” (283). ↵

- For a recent account of “the overwhelming whiteness of BDSM,” and more generally the role of race and racialized gender in kink communities, see Katherine Martinez, “The Overwhelming Whiteness of BDSM: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Racialization in BDSM,” Sexualities 24, no. 5–6 (2021): 733–48, https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460720 932389. See also Ariane Cruz, The Color of Kink (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014); and Amber Jamilla Musser, Sensational Flesh: Race, Power, and Masochism (New York: New York University Press, 2014). ↵

- The plenary session on “Queer Natures: Bodies, Sexualities, Environments” at the 2017 Shakespeare Association of America’s annual meeting in Atlanta presented important work on this topic by Karen Raber, Joseph Campana, Vin Nardizzi, and Laurie Shannon. See Karen Raber et al., “Queer Natures: Bodies, Sexualities, Environments,” (plenary panel session, Shakespeare Association of America, Atlanta, GA, April 7, 2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YVgx9-6wTOE. Lyly’s Galatea is cited in Laurie Shannon, “Nature's Bias: Renaissance Homonormativity and Elizabethan Comic Likeness,” Modern Philology 98, no. 2 (2000): 183–210, https://doi.org/10.1086/492960. ↵

- Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (New York: Penguin, 2019), 118. ↵

- Lyly, The Woman in the Moon, 62. ↵

- Kesson, “The Women in the Moons.” ↵

- Valerie Traub, Thinking Sex with the Early Moderns (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 123 (Traub’s emphasis). See also Joseph Gamble on “sexual-logistical knowledge” in “Practicing Sex.” ↵

- For a fuller account of “amorous,” see Jeffrey Masten, Queer Philologies: Sex, Language, and Affect in Shakespeare’s Time (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 157–59. ↵

- Andy Kesson, “The Woman in the Moon Onstage,” Before Shakespeare (blog), August 19, 2017, https://beforeshakespeare.com/2017/08/19/the-woman-in-the-moon-onstage/. ↵

- Lyly, The Woman in the Moon, 90. ↵

- Scragg compares Pandora’s language with Ophelia’s sexually charged language in act four, scene five of Hamlet. See Lyly, The Woman in the Moon, 128. ↵

- See “A Beginner’s Guide to Subspace,” Healthline.com, accessed 16 December 2022. https://www.healthline.com/health/healthy-sex/subspace-bdsm. ↵

- Julie Fennell, “‘It’s all about the journey’: Skepticism and Spirituality in the BDSM Subculture,” Sociological Forum 33, no. 4 (2018): 1045–67, at 1060, https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12460. ↵

- See “What is Sub-drop?” in “A Beginner’s Guide to Subspace,” Healthline.com, accessed December 16, 2022, https://www.healthline.com/health/healthy-sex/subspace-bdsm. ↵

- Interviews quoted in Charlotta Carlström, “Spiritual Experiences and Altered States of Consciousness: Parallels between BDSM and Christianity,” Sociological Forum 33, no. 4 (2018): 749–66, https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460720964035. Carlström cites sociological research on “reality slips” in her work on Christian glossolalia and BDSM subspace (761). ↵

- Quoted in Karmen MacKendrick, Counterpleasures (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1999), 79. Rilke’s original reads, “zu knien: daß man die eigenen Konturen, / die auswärtswollenden,” with “Konturen” usually translated into English as contours or outlines. ↵

- Kesson, “It is a pity,” 41. ↵

- Fleabag’s crisis is doubly complex because the character, played by Phoebe Waller-Bridge, is also the writer/creator of the series. ↵

- I am grateful to Joseph Gamble for sharing this poem with me. Davis’s opening lines set a familiar scene: “The moon assumes her voyeuristic perch / to find the rut of me, releashed from sense” (my emphasis), Imani Davis, “Kink,” Poem-a-Day, Academy of American Poets, February 3, 2023, https://poets.org/poem/kink?mc_cid=031c76dab8&mc_eid= 307c62b1f7. ↵

- Jillian Keenan, author of Sex with Shakespeare: Here’s Much to Do with Pain, but More with Love (New York: William Morrow, 2016), self-identifies as “what the kink community calls a ‘brat’ — someone who is a bottom, but has a play style that is more sassy or combative” (94). ↵

- Angel, Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again, 149. Angel’s emphasis. ↵

- MacKendrick, Counterpleasures, 12. ↵