Introduction

Historical Context

A scandalous novel, now known to us as The Island of Hermaphrodites,[1] was circulating in the streets of Paris in 1605. A satire of the French court, it was quite popular, selling for the exorbitant price of two écus.[2] Yet Henri IV (1553–1610; reigned 1589–1610) refused to punish the author, whose name did not appear anywhere in the book but who apparently was known nonetheless. This supposed author thus escaped the tribunals established to suppress anti-monarchical [2] works.[3] Most scholars connect this novel to the court of Henri III (1551–1589; reigned 1574–1589), often criticized for its wastefulness and corruption, to the Valois king himself and his courtiers, who were accused of sodomy in the polemical literature of the period.

This novel appears in the wake of the French Wars of Religion (1562–1629), that is to say, after the Edict of Nantes (1598), which has often been considered the end of these wars, but well before the final siege of La Rochelle (1627–1628) and the Edict of Alès (1629), which eliminated the last fortified city under Protestant control.[4] During this period, eight wars ravaged a wide area of [3] France,[5] with two to four million people dead from war, massacre, famine, and disease.[6] The violence of these wars is evoked constantly but subtly throughout the novel and is more overtly addressed in the parodies of political treatises that are inserted near the end of the narrative.

These evocations of the wars can be seen as a response to the official suppression of all mention of them, whether in speech or in print. The policy of oubliance, a policy of deliberate forgetting of these wars,[7] resulted in frequent royal edicts commanding that the events of the Wars of Religion should be treated as dead and buried, even as these wars were ongoing. This prohibition was first stated in the Edict of Amboise of 1563:

We have ordered and order, intend, wish, and it pleases us, that all affronts and offenses that the iniquity of the times, and the events which have occurred, could have given rise to among our said subjects, and all other things that have happened and were caused by the present agitations, remain extinguished, as if dead, buried and never having happened.[8]

This command that the past be buried—echoed in the Edicts of Saint-Germain (1570), Boulogne (1573), Beaulieu (1576), and Bergerac (1577), as well as in the Edict of Nantes in 1598—calls to mind the very violence that these edicts seek to efface. Orders to forget did not have the desired effect, as literary and historical works commemorating or evoking the violence proliferated in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

The seemingly disparate sections of this novel, focusing at first on the material aspects of court life, then offering a long list of parodic laws and two political [4] treatises as well as a poem denouncing the “hermaphrodites,” gain greater coherence when read in the context of these religious wars. All of the descriptions, many of the laws, and the entirety of the treatises allude to the violence of these wars either directly or metaphorically.

The Work: Assumed Author, Characters

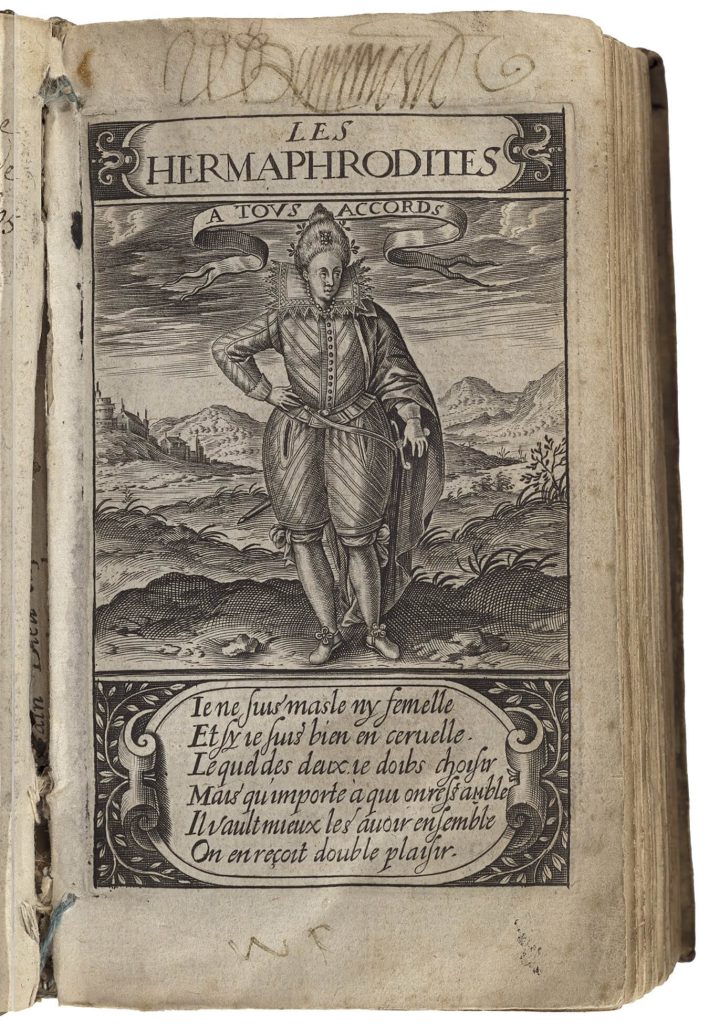

We know very little about the author of The Island of Hermaphrodites, and most scholarship on this novel respects the original anonymity of the author, since the novel was published without a title page and thus without authorial attribution, date or place of publication, or publisher. Pierre de L’Estoile, who wrote extensive journals over the course of the reigns of both Henri III and Henri IV, claims the author is Artus Thomas (perhaps Thomas Artus), who completed de Vigenère’s translation of the History of the Decline of the Greek Empire.[9] Artus Thomas also added epigrams to the translation of Images or Paintings of the two Philostrates;[10] the style of these poems seems to echo that of the opening lines of The Island of Hermaphrodites. He also produced works on Catholic doctrine and, according to Ilana Zinguer, a proto-feminist work supporting the education of women.[11] A dialogue against slander is also attributed to him.[12] This body of work suggests a fairly broad range of knowledge, reflected in encyclopedic descriptions offered in The Island of Hermaphrodites of architecture, clothing, court tableware, menus, and furnishings, Galenic dietary theories and practices, laws, and political philosophy.[13] This introduction will offer some background on these bodies of knowledge.

The main characters of the novel are called “hermaphrodites,” but their identities are not directly related to any bodily form, as they are fully covered by clothing, masks, veils, and gloves.[14] As Claude-Gilbert Dubois points out, not only does the term hermaphrodite refer to a “biological reality” but it also becomes a political term, one particularly directed at political moderates who advocated for [5] religious toleration and who were accused by religious extremists as being incapable of choosing a side and therefore of having a double nature.[15] Dubois briefly reviews the foundational myth of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus, in which the nymph, enamored of the son of Hermes and Aphrodite, asks the gods to join the two of them together in eternity. Her wish is granted, but in Ovid’s version of the myth, Salmacis’s identity disappears entirely, and only a weakened or effeminate Hermaphroditus remains.[16] This version of the myth seems to inform the novel’s representation of the “hermaphrodites” in some scenes, when they are putting on makeup or having their hair curled in ways that evoke feminine fashion of the day. This obsession with fashion and with bodily aesthetics reflects accusations of effeminacy and of homosexuality in political pamphlets criticizing the court of Henri III of France, and in particular the mignons, his followers, known for their elegant dress.[17] However, it is also suggested in the dressing scenes that the “hermaphrodites” use clothing to change gender roles at will, and in various parts of the novel, they are referred to as Lordladies (Either Seigneursdames or Syresdones, the latter taken from a French word for lord, sire and the Italian word for a lady, donna), thus suggesting what today we would consider to be crossdressing, genderqueer, transgender, and intersex identities.

Sixteenth-century medical discourse presents a range of possible bodily configurations that fit into the definition of a “hermaphrodite.” Ambroise Paré, for example, lists four different possible types of “hermaphrodites” in his treatise, On Monsters and Marvels: the male hermaphrodite, the female hermaphrodite, the neuter hermaphrodite (one that displays characteristics of neither sex predominantly), and the double hermaphrodite (which displays characteristics of both sexes).[18] Both of these sources for understanding the figure of the hermaphrodite were very accessible in the culture of the late sixteenth century. Political pamphlets were widely distributed during the Wars of Religion and there was [6] a proliferation of medical treatises concerned with non-normative bodies more generally, but with gender ambiguity more specifically.[19]

Scholarly and Critical Approaches

Most of the scholarship of the last few decades on The Island of Hermaphrodites has offered an analysis of the novel as a satire of the sexual behavior of members of the court of Henri III or that of Henri IV. The novel was seen as purely dystopian, with the “hermaphroditic” inhabitants of the island used as negative examples in order to validate binary gender norms and promote other norms of political and social behavior.[20] David Fausett offers a more nuanced analysis, noting about The Island of Hermaphrodites that “the author’s satirical intentions seem to range more widely than Henri and his court.”[21] Fausett evokes the strange politics of this novel, calling the society represented an “involuted, ‘poststructural’ society” in which there is a “total abdication from authority.” He sees in the narration “a striving for social realism and a critical response to the rise of political absolutism. The latter was, perhaps, seen as intensifying a quasi-erotic relation of mastery and subjection between state and subject.”[22] This critique of a nascent absolutism is made explicit in the political treatises inserted at the end of the narration. Fausett’s observation of the connection between the sexual mores of the “hermaphrodites” and this anti-absolutist, even anti-hierarchical, stance is echoed by Todd Reeser’s analysis of the link between gender ambiguity and social disorder in the novel.[23] So, while most critics recognize a political aspect [7] to the novel, the understanding of the nature of this aspect differs somewhat among them.

Some scholarship has noted the contradictions and range of different perspectives evident in the novel. Ann Rosalind Jones and Peter Stallybrass noted the “proliferating possibilities” that arise from the “reversal of laws of sexual difference.”[24] Gary Ferguson has observed that this is “a far from straightforward text” and that satire and utopianism seem to coexist like conjoined opposites in this work.[25] This complexity has been analyzed in depth by Teodoro Patera, who proposes the aestheticism of the “hermaphrodites” as a counterpoint to the narrowly moralizing commentary that runs through the novel. This aestheticism can be seen as troubling the binary division of gender into male and female roles, creating an ethics of alterity that can allow the novel to be read as a new, less normative, form of utopia.[26] I would add that this ethics of alterity stands in stark contrast to the massive violence of the French Wars of Religion, which are alluded to throughout the novel. The storyteller, who starts out being very judgmental about the gender expression of the inhabitants of this island, keeps mistaking their behavior for the violence he has left behind in France, seeing scenes of torture and execution where in fact no violence is taking place. His projection of the violent and rigidly hierarchical society from which he has exiled himself onto the behavior he observes on this island is frequently made quite evident.

The World of the Court

The narration presents a seemingly ethnographic encounter between a French man and a culture he presents as strange to him, even if it evokes many French practices and laws. This double focus on France as at once itself and alien to itself is already presented in a frame narrative at the beginning of the novel that introduces the storyteller as a man who leaves France in order to avoid shedding the blood of his fellow men.[27] He travels to the New World, deciding to return [8] only when he hears that an “august” king has established peace in France.[28] Shipwrecked with several other men, he finds himself on a floating island with no fixed location, somewhere between the “New World” and France.

This shipwrecked man begins his narration with a description of the architecture of the palace in which the rest of the action of the novel will take place. This action consists largely of him moving through the palace, observing various scenes of court life. He then describes scenes that recall the ceremonies known as the lever du roi (the levée, or rising, of the king), focusing particularly on clothing and makeup. After this, he is given an abridged list of the laws of the land, which are inserted into the narrative and constitute nearly one-third of the text. He then attends a banquet and describes at length the tableware and the food served, which evokes recent adaptations of the long tradition of Galenic dietetics such as the work of Joseph Du Chesne (1544–1609), one of Henri IV’s court doctors. He also attends the supper the servants eat after the banquet, offering a contrast between the behavior of the wealthy and that of the working classes. Finally, his guide through the palace gives him a poem and two treatises in the form of pamphlets. One treatise exhorts the subject to suffer anything for the sake of the sovereign, while the other denounces this culture of suffering. The first text parodies the political philosopher Jean Bodin’s (1529–1596) defense of absolute monarchy,[29] while the second evokes Michel de Montaigne’s (1533–1592) political thought, more focused on peaceful inclusion of differences in the system of government. At this point, the storyteller is moved to return to France, and the frame narrative breaks into the account of this strange island to note an audience that demands to hear more. The implication is that the storyteller never ceases to talk about the island he visited and so is still drawn to this seemingly unfamiliar culture.

Consisting largely of prose texts in various styles (utopian fiction, legal documents, political treatises), and some poetry, this work seems to be closest to Menippean satire in form. Menippean satire became more widely familiar in France toward the end of the sixteenth century, when Lucian of [9] Samosata’s works were translated into French.[30] The best-known French example of this literary form is the anti-Catholic Satyre Ménippée de la vertu du Catholicon d’Espagne (Menippean Satire on the Virtue of the Spanish Catholicon),[31] published in response to the excesses of the Catholic League, which sought to eradicate Protestantism from France and to prevent Henri IV from gaining control of the country. Menippean satire is a combination of prose and verse, with a range of discourses—legal, theological, scientific, philosophical, literary—reflecting multiple perspectives. This genre often has a political orientation, as Howard D. Weinbrot has observed relative to ancient Menippean satire.[32]

Like the Satyre Ménippée, which placed all of the narrative in the context of one building (the Louvre), The Island of Hermaphrodites places all of the action in a palace that evokes the Louvre and other royal palaces, which the storyteller explores as he observes the behavior of the island’s inhabitants. Thus the novel combines the style of Menippean satire with the typical elements of travel journals, as the storyteller’s observations of the behavior and material culture of the “hermaphrodites” forms its narration.

The Setting

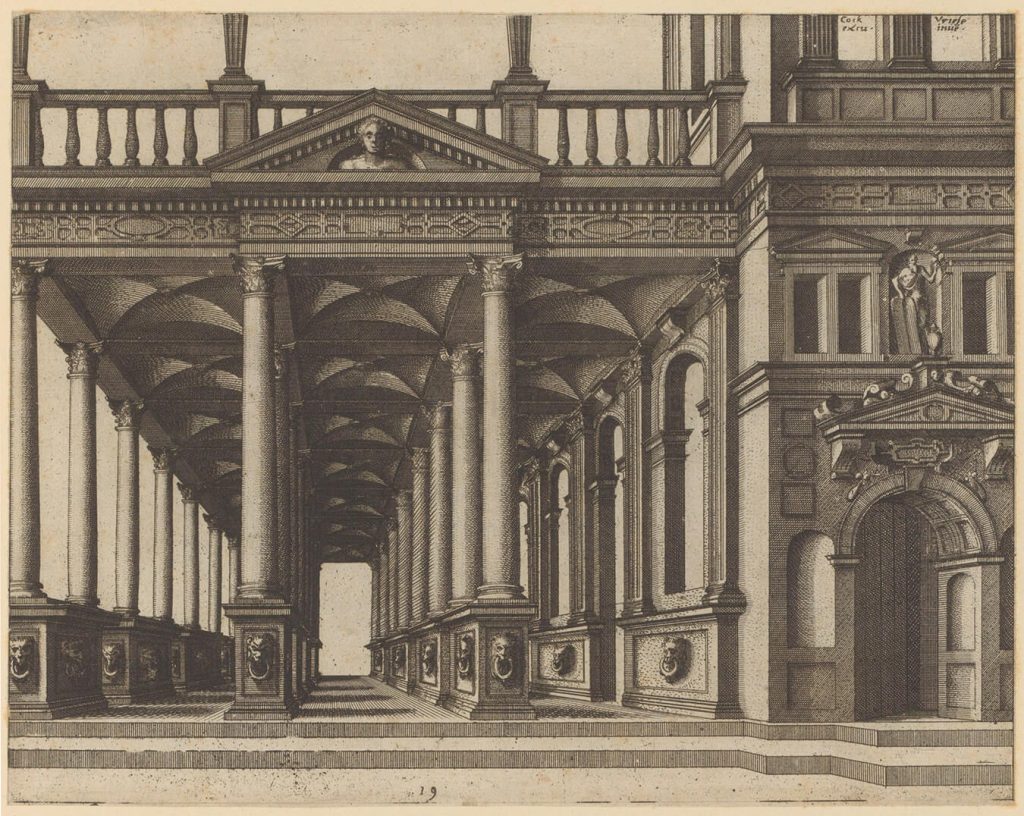

The first action the storyteller takes in this novel is to approach the palace he first encounters as he explores the island upon which he is shipwrecked, and which he already knows is called “the Island of Hermaphrodites.” While the description of this palace recalls aspects of some well-known French royal palaces, with the Caryatid columns evoking the sixteenth-century Louvre, the excessive and strange ornamentation signals a more utopian structure:

In the meantime, we went to contemplate a building fairly close to us, the beauty of which so ravished our spirits that we thought that it was an illusion rather than a real thing. Marble, jasper, porphyry, gold, and a variety of enamels were the least of it, for the architecture, the sculpture, and the [10] order we saw encompassed in all its parts so drew the spirit into admiration that the eye, which can see so many things in one instant, was not sufficient to take in all that this beautiful palace contained.

[. . .]

We first found a long Peristyle or row of Caryatid columns, which had as their capitol the head of a woman; from there we entered into a great courtyard where the pavement was so lustrous and slippery that we could barely keep on our feet. Nonetheless the desire to continue made us stumble towards the great staircase, in front of which there was an entryway surrounded by twelve columns, accompanied by a formal doorway so superbly ornamented that it was impossible to contemplate it without being dazzled. Above its architrave an alabaster statue was visible, its body half-rising from the sea, which was pretty well depicted by various sorts of marble and porphyry. This statue was as well-proportioned as could be and held in one of its hands a scroll upon which was written the word Planiandrion.[33]

The architectural plenitude, filled with statues resembling humans, or at least parts of human bodies, is counterbalanced by the initial lack of living human inhabitants in this place. This is an ominous scene. Still, when the storyteller and his companions move past this façade, they do see a crowd of people. This disturbing moment underscoring lives not present serves as a reminder of the violence they have left behind. [11]

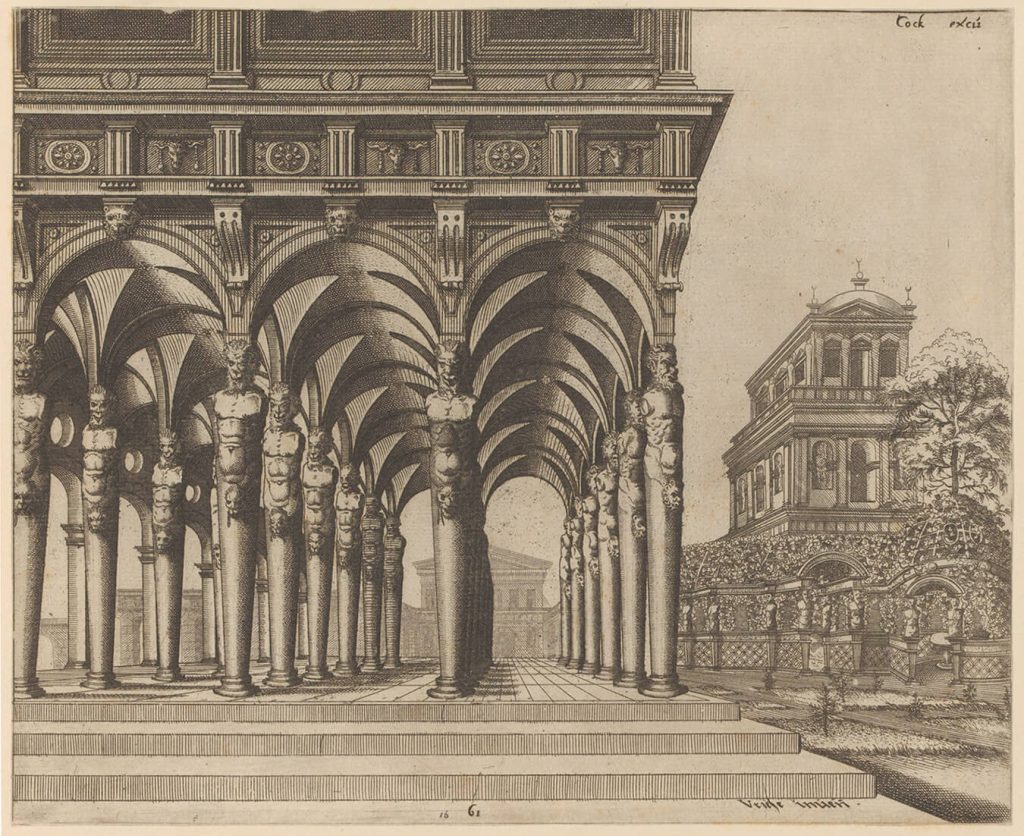

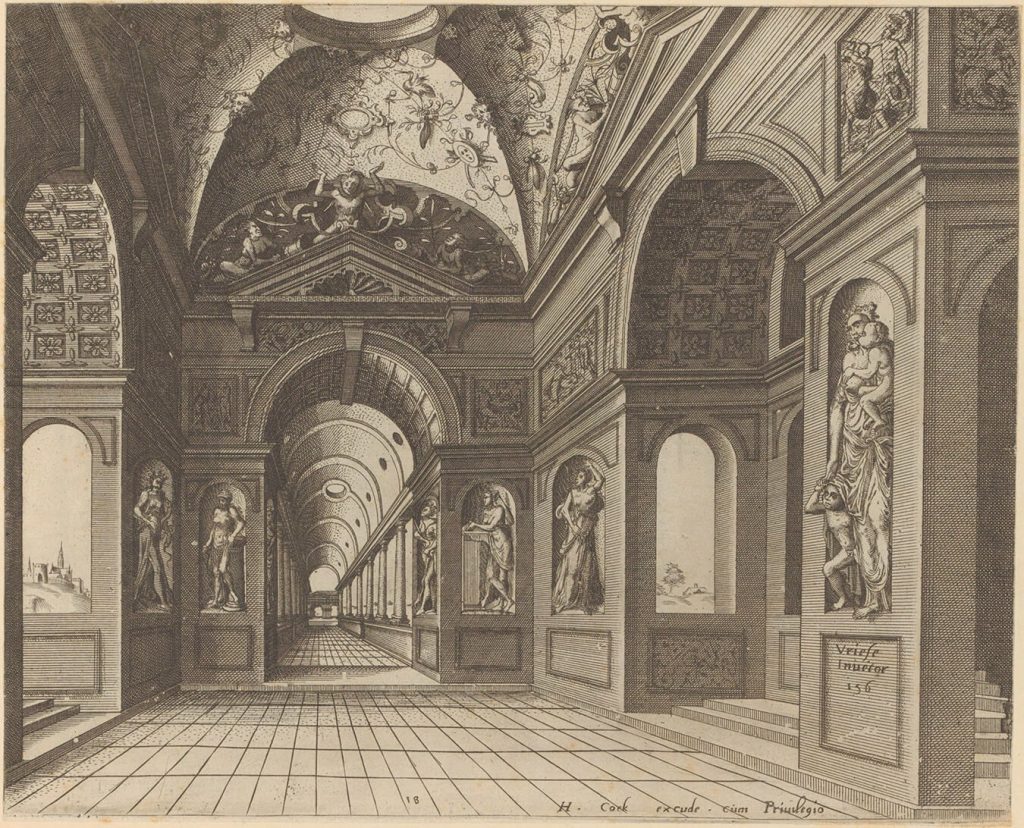

The initial absence of inhabitants also raises the question of whether these representations of body parts are simply architectural adornments or whether they have a more memorial purpose. This question can also be raised relative to the architectural works of Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527–c.1607),[34] a Netherlandish artist and architect who was active during the period of the Wars of Religion in France and whose architectural engravings were disseminated in numerous editions throughout Europe well into the seventeenth century and would have been easily available to the author of The Island of Hermaphrodites.[35] Vredeman de Vries produced a large quantity of beautiful but disturbing architectural drawings as well as perspective exercises. These designs constitute impossible models for construction and almost never represent an actual building; in this sense, they can be seen as utopian (in the sense of existing nowhere) buildings rather than any representation of the real, just as The Island of Hermaphrodites represents a utopian society that has no actual geographic or historical location. These engravings also play with perspective, signaling the illusion of reality that this technique enables and underscoring “painting’s incapacity to adequately represent something not there.”[36] Yet, even as they underscore their own distance from reality, these works also gesture towards the horrifying reality of religious violence at the end of the sixteenth century.

The exaggerated perspective in these works both pulls the viewer in towards the vanishing point and creates a profound sense of disorientation, because of the impossibility of the scene as well as because of the off-center positioning of the scene and its viewer. These scenes are also largely empty of live human bodies, but body parts peek out of many locations (and the more you look, the more of them you see), sometimes looking at you looking at them. The effect of this work is thus both beautiful and terrifying. [12]

Vredeman de Vries’s works have been enormously influential from the seventeenth century to the present day in the domains of architectural and set design and on early modern and modern city planning. His work also inscribes itself into the context of classical theatre, as the title of one of his works on perspective (Scenographiae) indicates and as Barbara Uppenkamp notes.[37] Uppenkamp [13] remarks on the link between tragedy and “the grand style of rhetoric” as well as “the superior subjects of mythology, history, and religion.” She points out that these subjects “were regarded as examples of moral or political conduct” and that classical architecture set the stage for this moral exemplarity. Highly decorated architecture was not only ornamental but also charged with moral and political meaning.

What remains elusive, both in The Island of Hermaphrodites and in the work of Vredeman de Vries, is what that meaning is. In an era of violent political and religious upheaval, one in which the usual tragic figures (kings, princes, and generals) have no moral standing as they have become a threat to their own people, [14] the usual architectural and social orders do not serve this straightforward exemplary purpose. This is clear in the final image in Vredeman de Vries’s Theatre of Human Life,[38] called “Ruin” (“Ruyne”), in which there is only “the absence of an order.”[39]

In The Island of Hermaphrodites, as in the works of Vredeman de Vries, formerly didactic performances and scenes take on multiple, contradictory roles, both presenting social and architectural norms and subverting them. This subversion integrates desire as elicited by vision as a motivating force tightly linked with the violent subtext of historical events that were supposed to remain buried but continue to reveal themselves everywhere. This violence, and the calm scenes [15] of pleasure that Vredeman de Vries also produced, are tightly conjoined, with the dead bodies and severed heads transformed into architectural grotesques and caryatids in the “peaceful” images.

Just as the narration of The Island of Hermaphrodites is driven largely by the space in which it takes place and the movement of the storyteller through that space,[40] along with the daily routines of the people whom he encounters along the way, so the subversion of gender and genre norms, of social hierarchies and sovereign power, is fueled by the strange representations of these spaces and the things found in them. The storyteller encounters far more tapestries and furnishings than he does human beings and tends to remark on the material objects in the palace more than he does its human inhabitants. This tendency to focus on objects is underscored when he first sees one of the inhabitants as a statue:

In the middle of the bed one could see a statue of a man half out of the bed, wearing a bonnet made almost in the same form as those of little babies newly dressed [. . .]

[16] His face was so white, so shiny, and of a red so striking, that one could well see that there was more artifice than nature involved, which led me easily to believe that this was only a painting.[41]

Here, and in the dressing scenes, human beings become part of the décor, sending complex messages about the connections and divisions between the material setting and the humans who inhabit it, as well as among various gender roles. The confusion between living beings and the material objects that frame them, between the ornamental parergon and the subject of representation is characteristic of the use of the grotesques in this period, as Heuer points out:

But there is a reverse to this idea of ornament as a cipher for (collective) identity, a reverse that Wölfflin himself later observed. This was the idea of ornament as a marker of individualism, of anomaly and difference—a role it often played in the late Renaissance. Grotesques, strapworks, hybrid monsters, vegetal homunculi, animalian nudes—this was the stuff of ornamentum, of ‘strangeness and variety,’ wrote Montaigne, ‘filling empty space.’ In court circles ornamental décor could speak a visual patois of secrecy and deviation.[42]

Frequently, both in Vredeman de Vries’s engravings and in The Island of Hermaphrodites, this grotesque ornamentation becomes the subject of the work, underscoring the centrality of that which we might think of as marginal. This shift in perspective underscores the craft of artistic and literary representation[43] and also signals the political significance of that which might otherwise be overlooked or deliberately buried.

Clothing and Gender in the French Court

The inhabitants of the island live in a decidedly material world. They do not believe in anything truly spiritual, including the immortal soul, heaven or hell, or any celestial divinity. They believe in a world of objects, and in fact create and recreate themselves by means of those objects. Thus the novel deploys a rich array of signs—architecture, clothing, language, laws, food—in the service of a pseudo-ethnography of a utopian or dystopian place, an island run by humans [17] of indeterminate or unstable gender. These people live in a luxurious palace, spend much of the day getting dressed, have strange laws that seem to overturn or mock French laws and customs, eat unrecognizable food, and constantly reinvent themselves, in part through their ever-changing fashions. The palace itself seems to change around them, as the storyteller returns several times to the room through which he entered it and finds this room to be different each time.

The capacity of the setting to be constantly transformed echoes the propensity of the “hermaphrodites” to create their own identities by means of clothing. Clothing was essential in this period for communicating information about rank or social status, as well as gender. Sumptuary edicts in France dictated who could wear cloth of gold or silver, as well as jewelry made of gold, silver, and precious stones, silk clothing, and other expensive materials such as lace. These edicts indicate that an increasingly wealthy bourgeoisie, particularly merchants, were wearing these items and thus blurring established lines of social caste.[44] They also imply that identity could be shaped, at least in part, by means of clothing. This is a recurrent theme in the novel, one played on in the detailed descriptions of various robes, waistcoats, shirts, collars, and shoes. We rarely see even a small part of the body of the “hermaphrodites,” and so the clothing comes to define their fluid identities far more than any bodily appearance. The novel thus describes almost every piece of clothing and every accessory in loving detail, from underwear to waistcoats, ruffs, sleeves and cuffs, shoes, stockings, hats, gloves, fans, parasols, and ornamental swords.[45]

The novel signals from the beginning that clothing is a deceptive sign. The first “hermaphrodite” the storyteller sees is wearing a bed jacket of white satin, lined with a material that resembles the silk velvet that was often used at the time in place of fur and covered in sequins instead of real jewels:

I saw that they went straight to a large and spacious bed, which, with the space it left between itself and the wall, took up a good portion of the room [. . .] He sat up, still sleepy, and right away they put a little coat of white [18] satin studded with sequins and lined with a material resembling silk velvet on his shoulders.

I had not yet seen who was in the bed, because neither the hands nor the face was visible. But the one who had put the coat on him came right away to lift a linen cloth that hung very low over the face, and to take off a mask that was not made of fabric, nor was it in the manner of those worn ordinarily by ladies, because it was made of shiny and tightly woven material [. . .][46]

The storyteller can see no part of the person who is in this bed because the face is covered with a veil and a mask, and the hands are gloved. But the material with which the coat is made already signals deception. In this passage, the storyteller assumes this figure is male, using mainly masculine pronouns, such as celuy qui estoit dans le lict [he who was in the bed].[47] He does become confused when this person complains, and then admits his ignorance of what lies before him: “I had not yet seen who was in the bed” [Je n’avois encore veu ce que c’estoit qui estoit dans ce lict].[48] The odd grammar of this passage, with its initial use of ce que, which means “that which,” underscores the ambiguity of qui, which can designate a subject that is human, a non-human animal, or inanimate, thus further confusing the categories of human and non-human.

This blurring of categories is echoed by confusion concerning the gender of the person being observed. When the storyteller sees a beard on this person’s face, he returns to using masculine pronouns, and when he returns to this room later in the novel and sees this “hermaphrodite” once more, he alternates between masculine and feminine pronouns, using le visage [the face] as the antecedent for the masculine, and ceste idole [this idol][49] for the feminine. By the end of the novel, he designates the inhabitants of the island by the doubly gendered honorifics of either Syredones or Seigneursdames [Lordladies]. The indeterminacy of gender signaled by this use of compound nouns is also underscored by the elaborate clothing of the “hermaphrodites.” [19]

The sartorial practices of the “hermaphrodites” reflect a blurring of gender lines in the use of particular articles of clothing during this period in France. Whereas certain materials were seen as more feminine, such as lace, the difficulty of fabrication and the relative scarcity of this material made it a sought-after element in clothing for male courtiers as well. Men’s increasingly elaborate ruffs often resembled those of women, even if the other forms of adornment that surrounded the ruffs were generally less elaborate than those worn by women.

Lace was extremely time-consuming to make in this period, and so was extremely expensive and a sign of a certain social status. The popularity of this form of adornment is evident from the number of lace pattern-books published in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, when lacework and ruffs both flourished as status symbols for the nobility and the very wealthy merchant class. Lacework had become increasingly elaborate over the course of the sixteenth century, with Italian pattern books published from the 1540s onwards offering the technical innovation of cutwork designs.[50] Catherine de’ Medici brought a Venetian lacemaker, Federico de Vinciolo, to France; his pattern-books, published at least nine times between 1587 and 1623, dominated lacemaking in and around the French court during the reigns of Henri III and Henri IV.[51] Vinciolo’s patterns emphasized cutwork (point coupé), and his work may have been familiar to the author of The Island of Hermaphrodites, who discusses cutwork at some length in the dressing scene. Cutwork is lace made on a piece of fabric, generally linen, from which parts of the fabric have been cut away in patterns, then edged in embroidery-like stitches.[52]

Collars and ruffs could frame the face or distract from it. Cutwork could reveal desirable parts of the body and cover any flaws or defects, thus “managing” what the observer could see. The dressing scenes in the novel emphasize the artificiality of appearances modified by the clothing, which at first seems to overwhelm the person being dressed. The collar is heavily starched, as the reference to parchment suggests. The act of dressing the “hermaphrodite” is compared to torture:

[20] Once this shirt was put on, the collar was immediately turned up in such a way that you might have said that the head was waiting in ambush. They brought him a doublet, on which there was a sort of little body armor to make the shoulders even, because he had one higher than the other, and right away the one who had given him the doublet turned down the large collar made of cutwork that I described above. I would have almost thought that it was made of some very white parchment, it made so much noise when it was handled. It was necessary to turn the collar down to such a precise length, that they had to raise and lower the poor Hermaphrodite until it was just right; you would have said that they were torturing him. When this was finally in the form that they desired, it was called the gift of the rotunda.[53]

Details of the clothing suggest that the “hermaphrodite” is being created as a beautiful object, an object of desire. The “body armor” is a corset, generally made of iron, to shape the torso in a uniform manner and straighten the posture, thereby normalizing any notable differences in the body (here leveling the shoulders). In the end, the body resembles an architectural construction, with the allusion to a rotunda evoking the large ruffs and collars that often surrounded the head.

The aesthetics of this framing of the body evoke a statue-like quality in the flesh that is revealed:

This doublet had a bit of a décolletage in front, as did the shirt, so as to show off the whiteness and smoothness of the chest; but beyond this opening, one also saw some cutwork lace through which the flesh appeared, so that this diversity made the object more desirable.[54][21]

The description of this dressing ceremony also would seem to suggest that the individual is constructed by his clothing:

After he was put together, someone came to turn up the large, embroidered sleeves that covered one-fourth of the arm, while another arranged the lace of the collar quite meticulously, because it had to be raised up in order to roll it better.

I also forgot to tell you that there was another collar attached to the collar of the doublet, of a different color than that of the doublet, cut out and puffed up everywhere, which folded and turned up in such a way that the collar of the shirt came over it, and it extended far out from the body of the doublet.[55]

The depiction of these items of clothing in very architectural terms links the inhabitants of the island to the constructions all around them. The elaborate layers of clothing such as the multiple collars of the waistcoat and shirt are the focus of the storyteller’s attention, as if the body is only a mannequin on which the clothes are displayed. Even in the description of the revealing cutwork, cited above, the body is called “flesh” and the “thing” (la chose) that is seen, thereby effacing its humanity.

There are hints at normativity in these descriptions as well, as clothing is used to disguise anatomical differences such as uneven shoulders, and as the poor “hermaphrodite” is raised and lowered to fit into his clothing, rather than the clothing being made to fit him. This sort of representation is contradicted in other moments, when clothing is made tighter or looser according to the size of the individual,[56] and when the storyteller sees chairs that adjust to the size of the person sitting in them.[57] This underscores a tension between the normative and non-normative aspects of the text.[58][22]

Pleated or gadrooned (à godrons) ruffs (called fraises in French)[59] were very much in fashion in late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century France. The most important “hermaphrodite” on the island, visited by the others in his bedchamber, is wearing such an elaborate ruff in bed and protests when they approach him too closely (vous me gastez ma fraize [you are ruining my ruff]).[60] Ruffs varied greatly from year to year, as styles came and went, and over time became more and more elaborate. In a court where many of the men were scarred from the numerous battles of the religious wars, ruffs became of way of framing these signs of warlike masculinity, as well as a way of covering them up. Too much lace on the ruff could be seen as feminizing, although the distinction between women’s ruffs and men’s was not always clear.

Henri III of France was often accused of feminine dress and behavior. His elaborate ruffs and hats were particularly noticed by the authors of satirical pamphlets. His mode of dress was evidently less sober than that of Henri de Guise; while it was not unusual for the king to be more richly dressed than even his noble subjects, this contrast was used against Henri III in many political pamphlets. This negative response to Henri III’s ornate clothing is evoked in the frontispiece of the novel.

However, several decades later, Henri IV was portrayed as wearing a lacy collar quite similar to one worn three decades earlier by Henri III. While Henri III was accused of effeminacy because of his clothing, seen as resembling women’s clothes, Henri IV’s very similar attire was then deemed masculine. This speaks to both the changing nature of fashion in early modern France and the changing attitudes towards dress and behavior as signs of masculinity.

These representations of fashion signal a few things: fashion was used to cover defects or flaws and to manage the spectacle that the individual was presenting to his public. This management frequently involved gesturing towards [23] the defect, particularly if it was a wound inflicted in battle during the Wars of Religion, in order to reinforce the appearance of manliness. But too much visibility of a less than perfect body might disqualify one’s authority, so this management was complicated, something like the game of peek-a-boo that the cutwork lace suggests. Fashion also signals more or less manliness, more or less femininity, thus signaling in itself the potential for a spectrum of gender, an idea much speculated on in this period. The question of luxury and excess is also present in these representations of clothing and raises the question of class distinctions signaled through clothing. These distinctions become problematic as wealthy merchants begin to wear items previously reserved to the nobility. Clothing both signals ability, gender, and class and also subverts these categories, becoming an unreliable sign of the body and its status in the late sixteenth century.

The Laws

After the storyteller is prevented from entering the wardrobe in the chamber of the most important “hermaphrodite,” where the “most secret councils” are held and the most private business discussed, he is led through a gallery full of paintings towards another room where other curiosities are displayed.[61] These curiosities include chairs that can be made longer or wider, be lowered or raised on springs, to suit the sitter. The objects face a row of statues representing the heroes of the “hermaphrodites”: Marc Antony, Nero, Otho, and Vitellius (all Romans who held power but who were accused of being too focused on pleasure), the medical authority Galen, Nero’s lover Sporus, Demetrius the actor, Apicius, the Roman author of a cookbook well-known in sixteenth-century France, Ganymede, Hermaphroditus (in the Aristotelian form of a man on one side, and woman on the other), the Assyrian emperor Sardanapalus, and the Roman emperor Heliogabalus.

Next to the statue of Heliogabalus is a reading desk holding a large book containing all the laws and customs of the inhabitants of the Island. Since the dinner hour is approaching, and our poor storyteller cannot possibly read the whole book, his guide takes pity on him and pulls out a printed summary of the most important laws from a cupboard where it is stored with satires and other similar forms of poetry.

Their proximity to the statue of Heliogabalus, known in the sixteenth century for his dissolute life, warns the reader that the laws themselves will be of questionable character. Pleasure is written all over these laws, even those laws concerning religion: “The greatest sensuality shall be taken in this Empire to be the greatest sanctity.”[62] The laws themselves are divided up into sections on religious [24] ordinances, articles of faith, laws concerning the legal system itself and the role of royal and state officials (la justice),[63] public policy (la police),[64] social rules (l’entregent),[65] and military laws (loix militaires).[66] These laws range from being anti-laws, that is to say the reverse of laws that existed at the time, to clever parodies that play on the hypocritical nature of certain edicts or ordinances. Many of the latter underscore the limitations on what the average person can do, while the king and his court are left unfettered by those limitations; these laws are often focused on excessive expenditures (for example, in many sumptuary laws, as mentioned above) or a troubling waste of resources (as in the ordinances concerning logging).

Religion

The laws begin as what might seem like straightforward satire, with a condemnation of the Roman emperors Trajan, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, and Severus, known for their creation of just laws and legal systems. The documentation of the “hermaphrodites’” laws is then justified as necessary to prevent the eradication of their culture.[67] The list of laws begins with language parodying that of royal edicts: “By our very certain knowledge, full power and authority, we have established, instituted, and decreed, and we establish, institute, and decree that which follows.”[68] The bombast of this royal formula is undercut by the irreverent ordinances concerning religion that follow: “May the ceremonies of Bacchus, and Cupid, and Venus be continually and religiously observed here, all other religions banished in perpetuity, unless it is for the purposes of greater pleasure.”[69] Religious hypocrisy is valued as a cover for debauchery: “We advise all of our subjects, when they encounter those who make a big deal of piety, which should be as rarely as possible, to speak with great zeal of religious devotion.”[70] These religious laws thus serve as the foundation of all others, and represent the [25] fundamental beliefs of the “hermaphrodites”: pleasure is more important than anything else, including virtue and reason, and appearances are more important than genuine adherence to values of any kind.

Yet these religious laws are rather vague, rarely touching on theological issues that were controversial during the period of religious wars. The pagan sensuality of the “hermaphrodites” is emphasized, as are their hypocrisy and irreverence, but the laws concerning religion are not as detailed as other laws, nor do they seem to be as pointedly directed at specific laws or behaviors as those in some of the other sections. Perhaps the author was trying to avoid revealing any particular religious sympathies.

The “hermaphrodites” choose rather to emphasize questions of etiquette in church. The answer to the question of whether or not to keep one’s hat on depends on the effect it might have on an elaborate hairdo. The laws debate whether one should kneel, more for the desired effect on others than for any religious reason, or what sort of book to read, with preference given to one about sensual love or pleasure.[71] One should flirt with lovers in church, with a “sacred band of Thebes” encouraging each other to feats of lust. Pretty words should have more of an effect than holy water on those attending services.[72]

Another concern of the “hermaphrodites” is holy days, which should all be devoted to bacchanals and which can take place every day of the year. This detail reveals the potential dual nature of “hermaphroditic” laws, as it mocks the numerous feast days, saints’ days, and holy days in the Catholic Church as well as the frequent partying of the nobility.[73] This novel seems to take on the self-indulgent excesses of the wealthy and powerful in both the Church and the State.

Some of the laws are meant to be shocking. The inhabitants of the island seem to be what we would call agnostic, but what would have been considered atheist and heretical in early modern France: “Let no one have any thought of death, or trouble their spirit, as to whether there is another life.”[74] Other laws seem simply silly, such as the law declaring that “The ordinary ministers of the temple will be singers, dancers, actors, and comedians, and all those of the same cloth.”[75] The readings during religious ceremonies consist of love poetry by Ovid, Catullus, Tibullus, and Propertius. The “hermaphrodites” refuse any set [26] religious hierarchy, preferring to elevate those who are most eloquent at expressing “the most secret mysteries of love.”[76]

Other laws focus on corruption, particularly the sale and assignment of religious benefices (domains or institutions such as abbeys or priories that generate revenue), often to wealthy laymen who pay a portion of the revenue from these benefices to a cleric who can perform the religious duties required.[77] The “hermaphrodites” also encourage conversion of members of the ecclesiastical hierarchy to their decidedly non-religious ways, exempting them from knowledge of or belief in the Scriptures.

While much of the text of these laws seems to focus on Catholic practices and institutions, the “Articles of Faith”[78] mimic Protestant confessions of faith, litany-like lists of the fundamental beliefs of a particular Protestant sect. The best-known of these is the Calvinist “Confession de Foi,”[79] often known as the “Confession de La Rochelle,” after the most important Protestant stronghold in France. The phrase that precedes so many of the articles of this confession of faith, Nous croyons [We believe], is turned by the “hermaphrodites” into something close to its opposite, Nous ignorons [We do not know]. The original confession states the belief in one God, whose existence and will is made manifest in the Bible and who is three beings in one. It also states that the first man, Adam, was created pure, but that Adam’s sin caused his descendants to be born sinful and that Christ was sent to save mankind from this sin.

While the forty articles of the Confession of La Rochelle go into quite a bit of detail as to the precise nature of God, his creation, and man’s sin and salvation, the articles of faith of the “hermaphrodites” are reduced to eight fundamental points of ignorance. The “hermaphrodites” do not know about creation, redemption, justification, and damnation, thus erasing most of Christian doctrine in one short phrase. They do not know of any temporality or eternity; they do not know of any other God but Love (Amour) and Bacchus. They do not know of any providence superior to human things, and believe only in random chance. Temporal pleasure is their paradise; they do not know of any other life but the present one. They know of no spirit other than that which is made visible by their passions (thus introducing sexual innuendo into their theology). They do not know that earthly things serve heavenly purposes. The text associates these beliefs with Gnosticism: “This is why we hold as folly any other communion than that which is found in our assemblies, which we believe cannot be maintained by any other [27] means than the ancient doctrine of the Gnostics.”[80] But these beliefs seem more in line with satirical representations of early seventeenth-century libertinage, a philosophical movement inspired by Michel de Montaigne’s famous question, “What do I know?” (Que sçay-je?).[81] These articles cleverly avoid a statement of non-belief or a potentially heretical statement of belief by invoking ignorance. This refusal of dogmatic belief—or, rather, of the imposition of any particular dogmatic belief—was the domain of a group of leaders known as the “Politiques,” who proposed religious toleration as a solution to end the violence of the Wars of Religion.[82]

Justice

The section on religious laws is followed by a series of what we would understand to be judicial laws or, rather, the reverse of most laws that would be familiar to sixteenth-century readers. And so, homicide and its variants patricide, matricide, and fratricide are not crimes if they benefit the person committing them. Adultery should be not only legal but also fashionable, as should rape, incest, and child trafficking.[83] It is hard to untangle the dystopian aspect of these anti-laws from actual practices during the Wars of Religion, when all forms of violence, including sexual violence, were used to intimidate or even eradicate populations.

In this context, the law concerning duels seems strangely mild, urging the king’s subjects to engage in them as rarely as possible,[84] to avoid striking each other, and to break them off at the first hint of violence. This law follows closely upon those permitting homicide and familial violence, marking a contrast with them in its weak attempt to reduce violence. While the novel takes on aspects of both Henri III’s and Henri IV’s courts elsewhere, there is no reference to the most infamous duel of the period, the duel des mignons, in which six of Henri III’s close courtiers faced each other in an inexplicably violent combat, resulting in the death of four of them. This deadly encounter took place just months after a decree requiring arbitration in matters that could lead to dueling. As François Billacois notes, “Clearly these preventive measures were ‘very badly observed,’ even in the milieu where the authority and power of the monarch were most [28] immediately felt.”[85] Decades after this event, works on dueling bemoan the senseless loss of lives in this particular duel.[86] Perhaps it was hard to wring satire out of such senseless violence.

Many of these laws also have a strangely subversive quality to them. For example, numerous laws involve the status and function of the family, but one law actually erases family relations entirely:

We do not intend at all that there be among our subjects any degrees of consanguinity, except in matters of goods and possessions, and for this consideration we have maintained the names of brother, sisters, uncle, nephew, first cousin, and others. We do not believe that in consideration of blood anyone can say that they belong to one family rather than another, because of the multitude of fathers that everyone might have, and the suppositions that could be made. This is why we abolish from now on and forever these names of father, mother, brother, sisters, and others, and so wish that only those of Monsieur, Madame, or others of similar honor, be used, according to the custom of various countries.[87]

If the familial identities of father, mother, and brother (etc.) do not exist, then how can one kill family members? An exception is made in the case of property, but the law seems even to undermine this use of familial identity, as it remarks that everyone could have a “multitude of fathers.”[88] The laws then call for legitimation of children born out of wedlock, and go on to mock marriage as a “ridiculous thing” altogether.[89] The laws of the “hermaphrodites” particularly promote [29] the freedom of women to choose their own sexual partners, without deferring to their husbands. This is a reversal of legal practices in this period, as a husband could do as he wished with little fear of punishment, and a wife convicted of sexual misbehavior would generally be severely punished. Since marriage—with the father, the patriarch, being the ruler of the family—was considered the basis and model for the French monarchy, this freedom would have been seen as particularly revolutionary.[90]

Further breakdown of civil society is marked by permission given to borrow from others without ever repaying them, and to steal outright.[91] As for resolving disputes, the richest person involved in them should always win.[92] Given the officially sanctioned role of bribery in the justice system of late sixteenth-century France, this seems more like a reflection of actual practices than a satirical exaggeration.[93] This corruption extends to those responsible for the royal finances, who use their authority to line their own pockets.[94] Those closest to the Prince should also be the agents of other princes, and treason in one’s personal interest is favored over loyalty.[95] This last law seems to reflect the fraught relationship between Henri III and his archrival, Henri de Guise, who had pretentions to the throne of France.[96]

The laws in this section thus take on a dual role, both suggesting a fictional society where the traditional patriarchal family has disintegrated and corruption at court is the norm and offering details that reveal actual disintegration and corruption [30] in late sixteenth-century France. The frequent use of hyperbole may lull readers into a sense that these laws are merely imaginary, but precise vocabulary brings them back to confront the reality of many of these issues. What makes them really elusive is their frequently contradictory nature, evident in the conjunction of laws concerning familial violence and those eliminating family relationships altogether. In this case, the laws simply cancel each other out. The only common ground in all of these laws is venality. Committing crimes or perverting justice for money is laudable, according to the laws of this land; this seems to be a criticism that would have purchase even today.

Policy

The section on policy takes on a number of actual edicts and ordinances of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in detail. Once again, reversal of existing laws is a frequent strategy. What is added to this is wordplay, innuendo, and even nonsense that seems to call into question the bases of these laws and the possibility of a functional state. This section begins with weights and measures, calling for reformers and officials who are responsible for carrying out royal policy to allow false weights and measures, and similar means of cheating customers. This first rule seems to be mocking Henri IV’s attempts to appoint officials to oversee weights and measures used in commerce.[97]

The second law is one that resonates differently with the reigns of Henri III and Henri IV: “The said officers will also permit all defamatory speeches and booklets against the honor of the Prince and his Estate.”[98] Many pamphlets against Henri III were printed during his reign, and many speeches were given inciting violence against him; there was little his officers could do to stem this tide of propaganda. Henri IV’s officers gathered and burned anti-monarchical books and pamphlets, even those against Henri III, but sometimes the king himself permitted an author to go free. The author of The Island of Hermaphrodites himself escaped prosecution only because of the leniency of Henri IV. [31]

The laws then turn to questions of bankruptcy, encouraging the protection of those who do not pay their debts.[99] The passages that follow combine satirical critiques in the form of reverse laws concerning profiteering from limited resources and strange wordplay that seems to call for the readers more focused attention on these problems. The first law concerns hoarding of wheat and wine in times of famine:

The years when wheat and wine are more scarce than is customary, principally in countries where it is not to be found in very great quantity, we permit our subjects to fill storehouses with them and to distribute them only in extreme circumstances, in order to draw more easily the bad blood of the public that is directed at them during the years of abundance and by means of a subtle alchemy convert it into their wealth.[100]

Starving the peasants into submission to cure them of seditious feelings becomes a sort of alchemy that enriches the wealthy landowners.

The law that follows focuses on policies concerning forestry and logging, which had become pressing issues since these resources had been greatly diminished as the result of extensive building projects, both public and private. This law begins with a very extended pun, stating that since some ancient Romans were carried through the streets to the sound of flutes, so supporters of the “hermaphrodites” who live near forests should be allowed to play woodwinds—des haut-bois, literally oboes but also a pun on “high woods”—whenever they like.[101] This is most likely an obscure pun on the phrase haute futaie, the type of forest most protected from logging. This is what we would call “old growth” forests, and French forestry practices allowed the logging of these trees in principle only every hundred years (at the most frequent). Often these forests would be protected by the less valuable taillis, trees that were cut more regularly and were most often not the prized oaks, chestnuts, and beech trees.[102] But the long, straight trunks of the haute futaie were sought after for building projects, and so were valuable resources that were therefore quite threatened already in the sixteenth century. An ordinance promulgated by Charles IX in 1563 already expresses fear [32] of over-exploitation of these forests and of the taillis, but also chillingly represents them only as resources for construction and for financial gain.[103]

The text then states that the supporters of the “hermaphrodite” cause should not have to distinguish between dead trees (bois mort) and non-fruit-bearing trees or trees of no value (mort bois).[104] Dead trees that were dried out could only be used for firewood. Trees considered to be of no value were trees that could be cut down for a range of everyday uses, as they neither bore any edible fruit or nuts nor were strong enough to use for building castles, churches, or ships. The trees for which logging was limited by law included not only trees we would now consider fruit-bearing but also oak, chestnut, and hazel trees, whose acorns or nuts could be used for human or animal consumption.[105]

The “hermaphroditic” version of this law then states that all trees felled by the wind can be used, adding, however, the perverse detail that these trees can also be felled by setting a fire at their base.[106] This law is hard to interpret, and thus evokes the complexities of various edicts and ordinances concerning forestry in the sixteenth century:

But we wish that all windfalls, whether someone has set their trunks on fire, or they have fallen in some other way, be wood they can keep for their own use, our intention being that all forests be of the same nature as the wood of Danaë, that is to say that the chief foresters can never mark them with the royal hammer.[107]

This reference is difficult to decipher. The French term for chief forester, gruyer, indicates that this is an officer of the king, responsible for protecting the king’s forest from theft. The trees marked by the king’s sign were supposed to be spared logging, either because they served as boundary trees to mark off what could be logged from what could not or because they were baliveaux, trees that had to be [33] left to repopulate the forest. This practice is quite different from the marking of trees by merchants who were allowed to log in designated areas and would receive a particular hammer to mark the trees to be logged and sold from an authorized court. Without the king’s mark on trees, they would be vulnerable to logging and thus would be “the wood of Danaë,” raining gold on those cutting them down just as Zeus came to Danaë in a shower of gold.[108] This law, then, replaces a complex system of protection, in which different marks or combinations of marks gave trees different statuses, with complete permission to log at will. In this, it reflects the reality in the forests of France at the end of the sixteenth century rather than the laws being passed to protect the forests. As with many of the satirical laws in this novel, this law signals the dissolution of royal authority. In this case, the hypocrisy of Henri III himself may have contributed to the situation, as Michel Devèze notes that although Henri passed laws expressing concern for the excessive logging that was taking place during his reign, he authorized much of this logging in order to support the royal finances.[109]

The officers of the king are allowed by the laws of the “hermaphrodites” to prune trees for aesthetic reasons (émonder), clear forests (esserter, perhaps essarter),[110] or prune dead or diseased branches (élaguer), wherever is most useful for them (as opposed to being beneficial for the trees). The text then evokes the practice of allowing logging by the foot, already condemned as problematic:

And when a deal is afoot to order a certain number of feet of these trees, we wish that this order not be taken literally,[111] as one commonly takes it, but according to their own understanding: that is, to count as many trees for a foot, as one ordinarily counts inches to compose a Royal foot.[112][34]

A Royal foot is somewhat longer than twelve inches. The more frequent abuse of logging by the foot was taking only the best trees and leaving the surrounding forest devastated. This was the practice that led to the reform that permitted logging by anyone other than the king only in areas not marked off by trees bearing the sign of the king, in order to limit the area of forest affected.[113] While the text is dominated by puns here, the length of the passages dealing with forestry seems to indicate a genuine interest in the problem of excessive logging. This is not surprising, given that the loss of forests in the late sixteenth century disturbed even contemporary observers.[114]

The final section of the laws concerning forestry permits the officers of the lowest rank to make deals with laborers living near the forest, allowing them to take the best trees for ordinary building purposes such as shingles or siding.[115] This is precisely forbidden by the edict promulgated by Charles IX in 1563 (cited above), which forbids the use of old growth oak, chestnut, or beech forests for ordinary use. The closing accusation that the forests are being exploited for money to fund drunkenness echoes the emphasis on parties in this novel but also signals the frivolity with which the forests were being destroyed in this period.

The laws that follow are simply reverse laws. One abolishes censorship,[116] which was the opposite of what was happening in the period of the Wars of Religion, as laws like the ordinance of Moulins in 1566 prohibited the publishing of defamatory books, not just theologically or medically suspect books (censorship of books in these last two categories was the domain of the University of Paris).[117] Another allows either the husband or the wife to divorce if they merely wish to do so.[118] Yet another calls for the execution of anyone wishing to speak on behalf of the public good.[119]

Another law clearly reverses the numerous sumptuary laws of the day (discussed above in the section on clothing):

Everyone will be able to dress as they fancy, provided that it be sumptuously, superbly, & without any distinction or consideration for their status or wealth. If a fabric being used, as precious as it might be, is not enriched with a superfluity of gold or silver embroidery, precious stones and pearls, and frequently without any propriety, we hold such garments to be vile, [35] cheap, and unworthy of being worn in good company, holding any modesty in this for a baseness of heart and a lack of spirit. We also hold as an almost general rule among ourselves, that such attire honors more than it is honored: for on this Island the habit makes the monk, and not the contrary.[120]

A series of royal edicts produced over the course of the sixteenth century forbade the wearing of cloth of gold or silver, embroidery, lace, borders, silk, or velvet by all but the royal family. These laws offered a striking contrast to the excessive expenditures of the Court itself.[121] While these sumptuary laws were aimed at enforcing strict social hierarchies, the “hermaphrodites’” version allows everyone to reinvent themselves by means of clothing. This law is echoed a few pages later in an even more playful manner: “Each person will also be able to dress as they fancy, however bizarre the design might be. . .”[122]

Feminine clothing is valued above any other style, and the fashions should change constantly.[123] To this end, everyone should have a personal tailor.[124] Even the furnishings should be as extravagant as possible, gilded and covered with silk wherever possible, especially the beds, which should be richly covered with silk and be placed on Turkish carpets sold in Egypt (cairins).[125] Lavish banquets shall be held, with even the omelets, dusted with musk, amber, and crushed pearls, reflecting the excesses of court dining.[126]

Charity should only be exercised as a means of keeping up appearances with the outside (non-“hermaphrodite”) world.[127] Children should be educated in a way that leaves them free and does not constrain or discipline them in any way; [36] they should learn about pleasure instead, so that they might grow up to be excellent “hermaphrodites.”[128] Poetic academies and contests (jeux floraux) are to be maintained as the best means of educating the youth in the doctrines of this culture.[129] Hospitals and clinics will be admired not for the help they can offer to those in need but for the money they can make for the wealthy and the comforts they can offer them.[130] Beggars will not be arrested or prosecuted, even if they are faking illness or injury, as long as they bribe the officers who would otherwise arrest them.[131] Pickpockets, thieves, and other criminals should also be safe from officers of the law by the same means (passing on some of their gains to these officers).[132] Slander and treason should not be punished; on the contrary, those who practice these forms of betrayal should be honored and admired.[133] Alchemy, which is linked to forgery in this novel, should be studied by everyone, including officers of the state, who should be well versed in alloys.[134] Those who have mastered fashion and other useless trades and wasting vast amounts of wealth are to be the most admired in this society.[135] The final law states that, since the admirable men of classical antiquity no longer exist, nor will other men of honor be found, immigrants will be welcome to the land of the “hermaphrodites” so long as they are corrupt.[136] If they stay, they can receive all of the honors of those who are citizens by birth, but they are free to go if they think they can pursue better opportunities elsewhere.

These laws oscillate between a satirical critique of the dystopian corruption at the Court and all over France and a utopian vision of a life of pleasure and of freedom from constraint. [37]

Social Relations

The next series of laws focuses significantly on language, as well as appearance and etiquette. The instability of the language in the land of “hermaphrodites” was already evident in the early scenes of the novel, in which the rulers are awakened and dressed in a parody of the ceremony known as the lever du roi [the rising of the king]. As they greet one of the powerful leaders, the language in which the courtiers address this person destabilizes binary gender, an important principle of organization for French:

To this bedside went the three people I have described above, and they began to invoke this idol by names that cannot be well represented in our language, because the entire language and all of the terms of the Hermaphrodites are the same as those which Grammarians call the common gender, and are linked as much to the male as to the female.[137] Nonetheless, since I desired to know what conversations they were having there, one of their retinue, to whom I had sidled up, and who knew Italian well, told me that they were extending a thousand praises to her perfections, and that among other things, they were strongly praising the beauty and whiteness of her hands.[138]

The language of the “hermaphrodites” cannot be translated into French because of this refusal of binary gender. Here the novel is evoking the concept of nouns with common gender, which can be either masculine or feminine. Such nouns are present in Latin, but French has reduced all nouns to either masculine or feminine gender.[139] In fact, the Latin language has four genders: masculine, feminine, common, and neuter (echoed by Ambroise Paré’s categories of the hermaphrodite). French has two; the language of the “hermaphrodites” only one all-inclusive gender. Our storyteller finds a courtier who knows Italian, who explains what the others are saying. In fact, in this passage, the gender identity of the person being addressed is unstable, and the storyteller presents them sometimes with masculine pronouns, sometimes with feminine ones. This passage thus tightly links grammatical gender and human gender identity, even while it is calling these structures into question. [38]

Later, the storyteller will find an interlocutor who speaks Latin and who will lead him into a gallery of curiosities, where he will encounter the laws of the “hermaphrodites.”[140] These laws describe a language that is consistently double in its function, offering both an evident meaning and a coded meaning that is quite different. The inhabitants of the island are encouraged to make words up, but all words should have these two meanings:

By grace and special privilege, we also wish that it be permitted to our subjects to invent terms and words necessary for civil conversation, which will generally have two meanings: one representing to the letter that which they desire to say, the other a mystical sense of pleasure, which will only be understood by their own kind or by those who have been their foot soldiers.[141] We add this requirement, that the sound be sweet in pronouncing them for fear of offending their delicate ears, with prohibitions against using others, whatever substance, property, or signification they might have of what one wishes to say. And so that continual use cannot result in any annoyances, we judge that it is appropriate that they change these terms every year, so that if in the long run the common people wish to use them, our subjects can still have their own particular language.[142]

Here, language is doubly unstable, with new terms being invented every year and with each term having two different meanings. In this double and mobile nature, this language thus evokes the variations of gender evident in the novel. Gender joins the masculine and the feminine, thus creating a doubled identity, but it is also mobile in its expression, taking on different roles for different purposes.

Language also supports and undermines communication, having one meaning for the uninitiated and another that is only understood in the circle of semblables (a term signaling “those people who are like us”). This word, which evokes language as a community-based and community-building practice, is difficult [39] to sort out here. Who are the semblables and what do they resemble? Since their identity is based on appearances and since their appearances change constantly, the concept of a group of people who are like them offers infinite possibilities of identity and of meaning that oscillate between all meanings and utter meaninglessness. This refusal of fixed expression echoes the refusal of clear gender division.

The laws link disorderly language to disorderly conduct, thus threatening the stability of the state:

Inasmuch as our subjects have among themselves many plots, conspiracies, schemes, and secret undertakings, either for love or for the State, we have permitted and do permit them to have henceforth and forever some language or jargon composed according to their whim, which they will give some strange name, such as Mesopotamian, Pantagruelian, and others. They will also use signs instead of words, in order to be understood in their most secret thoughts by their fellow initiates without being discovered.[143]

Here the range of language becomes even broader, allowing even for signs to take the place of words. While the reference to Rabelais underscores the comic nature of this law, the insistent connection between language and civil order or disorder reveals the importance of language both as a tool of the state and a means of subverting it. The word fancy (fantaisie) links the work of the imagination to desire, and the instability of language to creative play and pleasure in defiance of social norms and political control.

It should not come as a surprise, then, that the next dozen or so laws focus on sexuality, flirtation, and other forms of love-play, including a suggestive list of games that might have served the purposes of seduction in the past but are also simply children’s games. The conclusion of this section of the laws then connects this seduction to power, but also to hypocrisy, as the good subjects and polite friends will always shape their desires and ideas to suit those of the person who might best advance their status, at least in words or appearance.[144] The ever-mobile and constantly transforming subjects shape themselves to suit those in power, but since this occurs only in hypocritical fashion, the result is a continual back and forth of power and resistance. [40]

Military Laws

The section on military laws unites the multiple thematic threads of disorder, obsession with finances and particularly with financial gain, and false appearances. While works discussing the organization of the French army, which was significantly reformed in the sixteenth century, were readily available,[145] these laws seem to be more a direct criticism of the ruinous cost and abhorrent behavior of the royal army during the French Wars of Religion. At first, the laws list Roman military roles, suggesting the order and discipline of Roman armies, but this order vanishes with a refusal of differences in rank.[146]

The laws call for the army to have far more servants than soldiers in their ranks: “we wish that the multitude of valets and others be three times larger than the whole army put together.”[147] Soldiers will have an easy life, since they will be billeted in the “best villages”[148] in every region where they are present. This leads quickly to the dedication of soldiers to the “Goddess of Ransacking”[149] and from there the descriptions of the soldiers’ behavior devolves into accusations of robbery and torture of the villagers. These accusations are echoed by puns on the concept of a mobile camp or camp volant, since voler means both to fly and to rob.[150] This violence is encouraged the laws: “When they encounter resistance, we permit them to use breaking, burning, rape, and ransom, even when this is against our own subjects (on whom they should profit more).”[151] Thus the army, rather than maintaining social order, is a threat against the citizens of this kingdom.

These accusations of theft and violence deployed against the citizens of their own country continue, even as the laws insist that the soldiers themselves should [41] face no risk of violence or privation. These laws place them above the law,[152] leaving them free to engage in crimes against the inhabitants of any town or city where their garrison might be located. The insistent theme of violence against the unarmed populace reflects the very real damage that various armies (royal and princely) inflicted during the period of religious conflict. As a result, this passage seems like the most serious and disturbing element of the novel, revealing the uses of disorder (a disorderly army) for the subjugation of a population and for the enrichment of both the army and its leaders. This denunciation gives a very different perspective on the complex interactions between power and resistance, suggesting the very high stakes of the behaviors described in other sections of the laws.

The Banquet: Galenic Dietetics and Court Life

The narration breaks off from the laws at this point, and the storyteller returns to his observations of court life in the land of the “hermaphrodites.” Although he is hungry, rather than going to eat with the servants, he persuades his guide to take him to observe a banquet that the “hermaphrodites” are about to attend. What follows is a detailed enumeration of royal tableware and of the food typically served at a royal or princely banquet. The dishes presented in this banquet and the order in which they are served reflect a particularly French take on a long tradition of dietetic advice based on the work of Galen (129–210 ad), one of the most influential medical practitioners, theoreticians, and authors of the ancient world, whose work on anatomy, physiology, pathology, and dietetics was widely disseminated and imitated in early modern Europe.

Galen’s presence was continual in sixteenth-century French medicine and indeed throughout early modern Europe.[153] His work on hygiene was published in Latin translation in Paris in 1526.[154] A Latin translation of his work on foods that generate good and bad humors was published in 1530,[155] and a translation of his other major work on food, De alimentorum facultatibus [On the Properties of Foodstuffs] was published in 1549.[156] Once these works became more readily available, they were quickly adapted: Charles Estienne’s De nutrimentis (On Food), [42] published in 1550, is the best-known adaptation of Galen’s own work on the properties of food produced in France during this period, and conveyed Galenic ideas to a largely humanist audience.[157] Estienne supplements Galen’s advice with lists and descriptions reflecting contemporary habits and preferences: the list of wines focuses on varieties familiar to early modern French consumers, with local knowledge concerning their properties. Galenic dietary principles are adjusted to the environments and situations in which they are invoked.

The history of the régime de santé (health regimen, also known as hygiene) was associated from at least the thirteenth century with treatises on the education of princes, and therefore it had a significant political aspect. The régime de santé was thus a well-established genre by the sixteenth century in France, having been developed in Italian courts at the end of the Middle Ages. This body of work consisted largely of adaptations of Galen’s writings on hygiene and on the properties of foods, but the evolution of this material was extensive, as Arabic and European authors alike added their own perspectives to the sources.[158] These works linked physiology and morality. Good self-governance and good government were particularly represented as closely related in later versions of the régime de santé. In addition, some of these works presented national or regional cuisines and habits, as some authors believed that the régime de santé should vary in response to individual needs in different environments and with different food cultures.

The early modern régimes de santé returned to the Galenic textual sources themselves, newly translated into Latin and occasionally translated or adapted into French. Although his influence in the domain of anatomy had declined by the second half of the sixteenth century, Galen was “the most important and towering figure in the field of medicine and dietetics,” and the mid-sixteenth century (1530–1570) was a period of renewal for Galenic principles concerning diet and hygiene.[159] Galen’s work and all of its early modern adaptations are based on the Hippocratic concept of the humors, particularly on achieving an equilibrium of hot, dry, cold, and moist foods, with condiments, sauces, and spices used to help achieve this equilibrium.[160] [43]