“Where do you go and how do you come back?”: An Exploration of Socially Constructed Knowing Through Multimodal Transmediation

Julia G. Houk

[print edition page number: 271]

This chapter presents a mini-unit designed to enhance the teaching of Shakespeare through multimodal texts. Performances of Shakespeare’s plays often are used to make texts “relatable” to students, as many teachers reason that watching one of his plays performed live creates additional opportunities for understanding since the visual medium may be easier for students to interpret than the four-hundred-year-old English text of written plays. However, teachers and students need tools and processes to unpack and interpret often unconsidered nuances of meanings in performances of Shakespeare. Contemporary audiences interpret texts in culturally reflective ways, marking considerable distinctions between how the text is interpreted by twenty-first-century audiences and audiences the text was first intended for. This means that teachers should be explicit about how the text’s meaning and impact on audiences has evolved over time. Engaging with a range of multimodal resources, texts like recorded performances, paintings and photographs of theatrical stages, character costumes, paintings and posters representing the literary work, and more, can deepen understanding.[271]

Engaging a variety of multimodal resources can open a text up and help situate and contextualize it for critical engagements. In this chapter, I describe a process of discovering where to go to learn more and how to return to a core text ready to engage anew, informed by myriad resources. This process invites students to explore a range of semiotic resources, think critically about their socially constructed meanings, and apply these analytic skills to performances of Shakespeare. Such an approach affords students the opportunity to deepen engagement with Shakespeare’s work through visual, embodied, and verbal modalities and access those unconsidered nuances of meaning.

Aligned with RaceB4Race (RB4R) scholarship, this chapter explores issues of race and identity embedded in texts and warranting inquiry by high-school students. These topics are valuable for inquiry because such topics reflect students’ identities, have sociocultural salience and relevance, and position literature in both contemporary and historical contexts. As secondary teachers often rely heavily on video productions of Shakespeare, this mini-unit begins with a video excerpt from a production of The Merchant of Venice (MoV), specifically Shylock’s “hath not a Jew eyes” speech (3.1), as the starting point for critical inquiry in English language arts (ELA) classrooms. The reading of this multimodal text (the video) requires the intentional use of and access to various student knowledges that are often not invited to the surface in K–12 classrooms. Students’ diverse insights and interpretations are prompted through exploratory talk, which refers to open-ended classroom conversations emphasizing observation, thinking, and connecting ideas (Barnes, 1976/1992). Generating knowledge benefits from multiple perspectives, knowledge sources, and lived experiences that spotlight nuance and that may shed light on the cultural, historical, or political significance of symbols and images embedded within performances of Shakespeare (Bordalejo, 2021).[273]

Exploratory talk helps learners interpret texts more expansively, and working across multimodal texts—each one contextualizing, challenging, or informing the next—allows teachers to observe how collective meaning-making can lead to deep critical insights. These readings of multimodal texts can be affective, allowing students to respond with their emotions (i.e., sensations, surprises, feelings) first. Interpreting multimodal texts is more expansive than traditional literary interpretation that relies on oral and written reasoning. More open-ended, affective, and text-based responses can be used to steer conversations about the different texts’ intended message, impact on the audience, authors’ creative decision-making, and more. These conversations then lead to further analytic discussions, consistent with the type of academic discourse students are familiar with in ELA. By building a rich foundation through exploratory talk, affective response, and collective meaning-making, students are able to bring these insights into critical, analytic conversations.

Additionally, I propose a manner in which a teacher may guide a multi-perspectival, resource-rich reading that facilitates critical engagement with texts. What can a class explore when students do not possess the knowledge or personal experience to read a semiotic text? (I wonder what that signifies? What does that image mean? How can we find that out?) Such student-led queries and tensions highlight the complexity of teaching multimodal texts, including recorded productions of plays. This process is enriched by iterative work: each new reading and engagement with the text extends both individual and collective understandings (much like the spiral curriculum model in Sanchez and Kiikvee’s chapter in this volume).

The BBC scene is the first multimodal text used in this framework. From this scene, I compiled several other texts to be read and analyzed as students grapple with complex questions of antisemitism and racialization, identity and social status, and patriarchy as students read MoV. Such[274] semiotic reading supports inquiry-based pedagogy and deepens understanding by linking concepts across texts and by extending the bounds of context (Harste, 2000; Siegel, 2006), weaving contemporary interpretations, individual identities, and historical readings into studying a text.

Design Framework

Multimodal texts combine semiotic resources to create meaning, and our world is saturated with them. From websites to advertisements, television, and recipes, we live in a world where our literacy practices are shaped by multimodality. Multimodal texts are often connected to the discipline of semiotics, an interdisciplinary field studying how meaning is made through images, sounds, gestures, and language. Semiotics looks at “meanings and messages in all their forms and all their contexts” (Innis, 1985, p. vii). For this reason, multimodal interpreting and composing are integral to literacy instruction (Siegel, 1995, 2006; Suhor, 1984) as meanings and messages come from all directions and across all types of text. For Harste (2000), “Every instance of making and sharing meaning is a multimodal event” (p. 4). When students illustrate stories, write fan fiction, make 3D replicas of a story’s setting, or roleplay fictional or historical characters, they make meaning across modes, and also transfer and translate understanding from one mode to another. This transference is referred to as transmediation.

In the ELA classroom, transmediation enhances literary interpretation and analysis. Transmediation creates opportunities for students to explore the ways in which meanings are informed by personal, historical, political, and cultural connections to text (Smith, 2019). Furthermore, transmediation benefits students who have been labeled as “struggling” or “unprepared” because it creates opportunities for them to generate and share knowledge (Siegel, 2006). The process of transmediating creates extended opportunities for deepening interpretation, as it necessitates collective inquiry and participatory meaning-making.[275] Teaching through transmediation also answers Mehdizadeh’s (2021) call for approaches to instruction that “model critical inquiry for our students” and challenge dominant paradigms.

Transmediation—the movement of meaning across texts and sign systems (visual, verbal, auditory, etc.)—supports student-driven inquiry by creating unexpected linkages, often with some tension or ambiguity to explore (Harste, 2000). Moving across sign systems is almost always ambiguous (McCormick, 2011), and meaning-making from ambiguity requires tapping into context to reinforce critical thinking. This kind of thinking is natural inquiry (Harste, 2000). Taking what we know from one sign system and recasting it in another requires invention and generative thinking (McCormick, 2011). Transmediation leads to more deeply connected and complex understanding (Magee & Leeth, 2014). In this process, there are limited opportunities for redundancy and static, inherited interpretations (Harste, 2000). Transmediation supports reflexive, generative thinking (Siegel, 1995, 2006; Harste, 2000) that is maximized by student discussion. Socially shared understandings are deepened when students position their interpretations and understandings alongside those of their peers in classroom discussion.

Engaging multiple perspectives can help students to see that understanding reality depends on whose perspective we take, and semiotic reading largely depends on the social position of the viewer. It is perspective-oriented. In culturally and linguistically diverse educational contexts, the particular knowledges and experiences of students are often relegated to the margins by canonical interpretations or hegemonizing teaching practices (Mehdizadeh, 2021). This is particularly relevant in the study of Shakespeare because reading Shakespeare in the secondary classroom has become prescriptive over time and because plays are usually taught through print, sometimes with read-alouds or recorded performances as supplements. Dramatic texts are multimodal and should be taught accordingly. Transmediation may benefit the study[276] of Shakespeare for the ways in which it sheds light on context and complexity, and disrupts canonical readings through ambiguity, socially mediated understanding, and reflexivity.

Mini-Unit

Overview: This mini-unit guides students through the process of discovering where to go, drawing from various multimodal resources, to deepen contextual understanding and how to return to a core text ready to engage anew. Multimodal resources can humanize and make visceral and relevant some elements of seemingly distant stories. Ideally, students have some familiarity with the core text before beginning these mini-unit activities.

Standards Connection: [CCSS.RL.11-12.7[1]] “Analyze multiple interpretations of a story, drama, or poem (e.g., recorded or live production of a play or recorded novel or poetry), evaluating how each version interprets the source text.”

Learning Outcome: Students will be able to analyze how elements of multimodal texts—e.g., background staging, character identity features, character dress—influence how a play is interpreted.

Lesson Sequence

Day 1—Lesson on Semiotics

Semiotics is a vast, dynamic interdisciplinary field, and students could spend an entire school year working through key ideas. Teachers do not need to dig deeply into semiotics. Through this lesson, key concepts can[277] be adapted into instruction. The central question is, how do we read non-verbal resources?

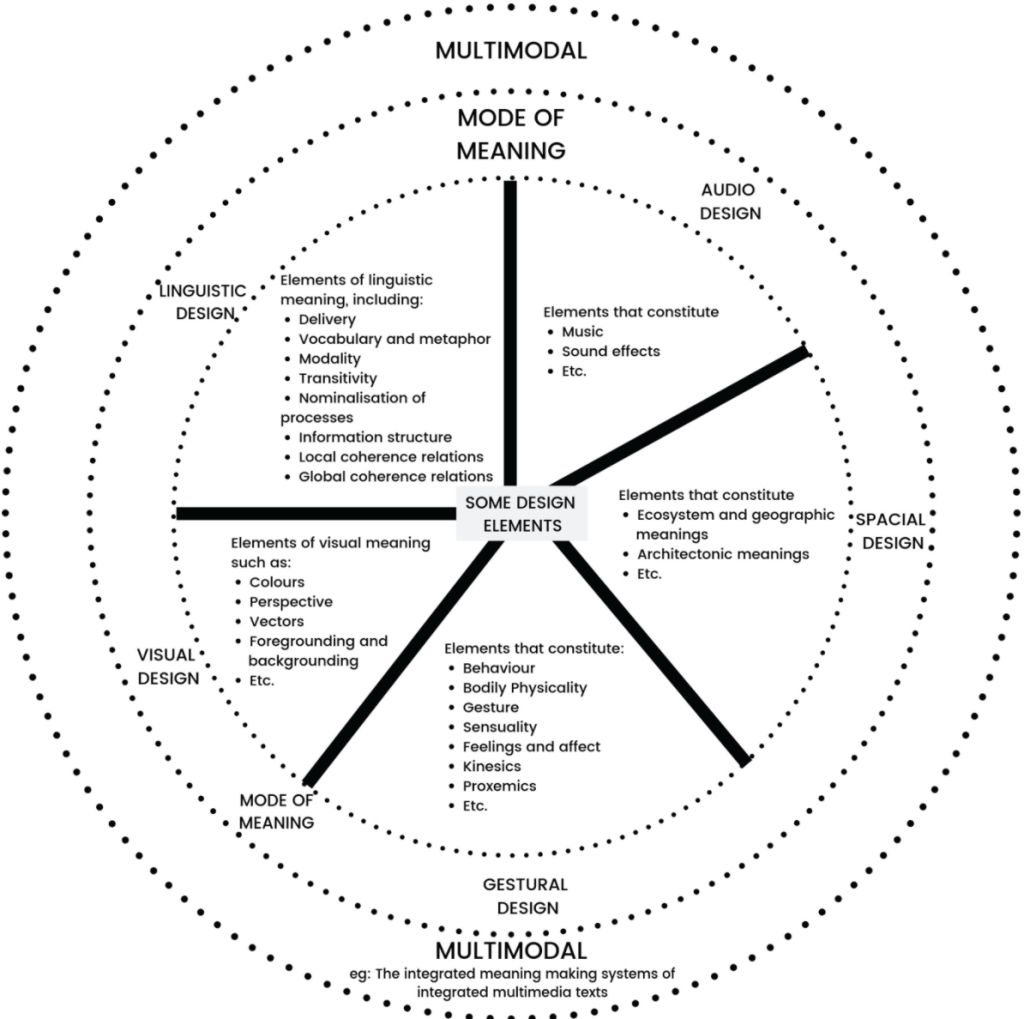

Figure 1, from The New London Group’s Pedagogy of Multiliteracies, provides a helpful breakdown of semiotic modes: linguistic, audio, spatial, gestural, and visual. Modes interact and combine to create intersemiotic[278] relationships. The combination of modes adds up to create meaning in a text. When analyzing multimodal texts it is important to identify specific design elements and analyze how they interact.

As an exercise in multimodal analysis, present students with popular brand logos (Nike, McDonald’s, Apple, Ford, etc.) and have students brainstorm together about what these brands represent or, in other words, signify. This is a valuable exercise because it prepares students for making sense of semiotic resources and for sharing their interpretations.

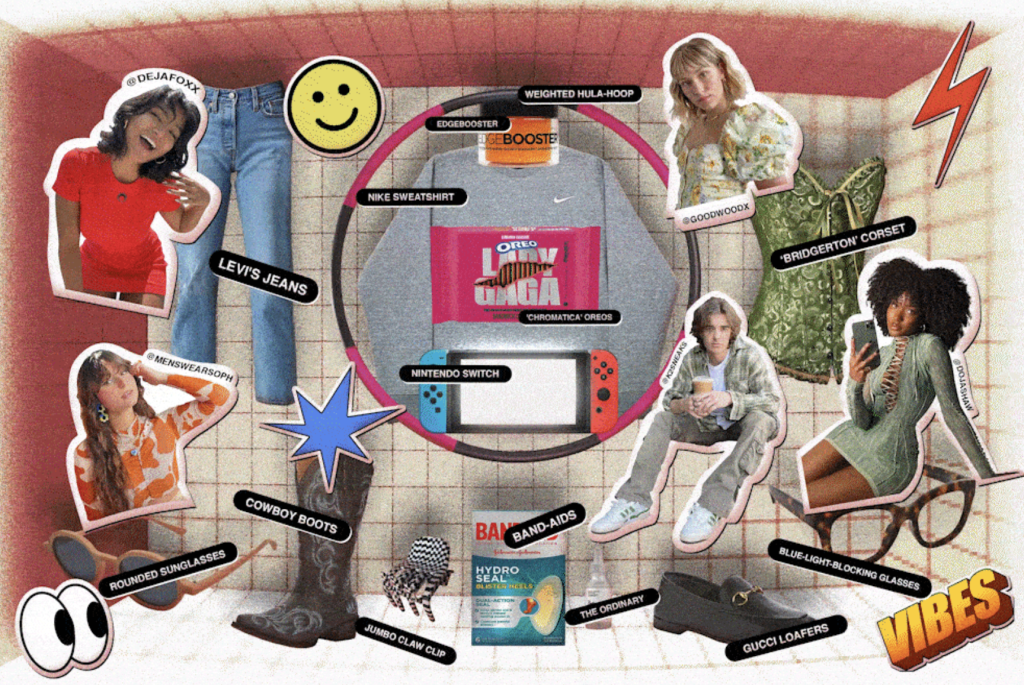

Another related activity is to have students brainstorm a list of current trends or style archetypes (e.g., VSCO girls, emo, cottagecore, etc. [Figure 2]).

[279]In such activities, teachers may find that students freely identify a range of semiotic resources, like brands’ social meaning, subcultural messages communicated through dress and material objects, how specific articles of clothing or accessories work together to communicate a social message, etc. Knowledge of what these various semiotic resources signify is an excellent example of social semiotics applied to daily life. Understanding semiotics as socially constructed is integral to the analytical process. Both suggested activities emphasize idea generation, discussion and debate, and shared knowledges, thereby scaffolding collective inquiry and meaning-making for practical use in K–12 classrooms.

Day 2—Setting the Stage

This lesson asks students to critically consider staging in theatrical productions of MoV (Figure 3-5), but any play with archived stage backgrounds[280] can be used. Present several different stage settings to students (this activity can also be done with paintings of the play), and ask them to describe what they see (listing as many features as they can), the mood of the set, and how that mood impacts how audiences experience and interpret the play. Potential prompts include the following:

- In as much detail as possible, describe the setting.

- What is the mood of the setting?

- How does the mood of the setting impact how the audience experiences the play?

Present questions one at a time and give students ample time to answer. Partners or small groups are recommended. After small-group work, whole group share-outs may help all students hear their peers’ ideas.[281]

[282]If students have computers or tablets available, they can search photo stock websites like Alamy.com for visual representations of characters and scenes from the play. Students can save and share images to discuss with peers using a live document like Google Slides or Jamboard.

Day 3—Reading a Scene for Social Semiotics

The text for this lesson is a video production of a scene from MoV. The goal of the activity is to observe and analyze the semiotic resources employed by directors and content creators.

Begin the lesson by reading the scene with students:[283]

The Merchant of Venice (3.1.52–72)

SHYLOCK

To bait fish withal: if it will feed nothing else,

it will feed my revenge. He hath disgraced me, and

hindered me half a million; laughed at my losses,

mocked at my gains, scorned my nation, thwarted my

bargains, cooled my friends, heated mine

enemies; and what's his reason? I am a Jew. Hath

not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs,

dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with

the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject

to the same diseases, healed by the same means,

warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as

a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed?

if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison

us, do we not die? and if you wrong us, shall we not

revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will

resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian,

what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian

wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by

Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you

teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I

will better the instruction.

(Shakespeare, n.d., Act 3, Scene 1)

With guidance, students can complete a quick analysis of the scene, for example, focusing on the use of rhetorical questions, the meaning of to bait fish withal, meter and rhythm, etc. Then show students the BBC scene (BBC, 2011 [Figure 6]). Students may need to watch it multiple times to observe enough details.[284]

The following activities can be done in small groups, individually, or whole-group structures.

- Observe and list: What do you notice in this production? (model a few; e.g., “Seems like a retail store;” “Maybe there was a break-in.”)[285]

- Discuss: How does the depicted setting influence how you react to the characters? What specific elements of the depicted scene relate to the storyline and emerging themes of the play? Why do you think the director made these choices? How do these production choices impact how the scene might be interpreted and understood by the audience?

- Reflect in writing: How do these adaptations change the way the audience reacts to and interprets this scene?

Day 4—Character Analysis

Studying character in literature study is central to standards-based work and the discipline of English. We often ask students to consider questions such as these: How is the character being constructed (directly, indirectly)? What details of the story reveal character traits? How does a character evolve across the arc of a text? Viewing performances of characters, however, invites attention to additional visual cues that serve as prompts for reflection on a particular embodied treatment of a character. The portrayal of Shylock, for example, reveals more than Shylock-as-I-understood-the-character-through-my-personal-reading and opens up a range of interpretive possibilities. Resources for interpretation include information about the context in which a performance is produced, the stances and attitudes of the producer(s), and the sociocultural factors that shape the production.

The lesson begins by drawing on a discussion guide for MoV created by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL, 2006) to address the antisemitism in the play. (Note: the discussion guide is available as a free pdf online.) From the discussion guide:

Throughout the play, the other characters consistently refer to [Shylock] as simply, the Jew. This characterization dehumanizes and de-personalizes Shylock and reduces him from a person to a category. During Shakespeare’s time, Shylock, and Jews in general, were portrayed on the stage as comical, yet villainous figures. . . . Jews were types, not people.

The mystery of Shakespeare’s intentions and the meanings of the play, in particular the intent behind Shylock, have [sic] allowed for numerous interpretations over the years. Since Shakespeare wrote MoV, Shylock has been played and seen as a comic buffoon, a cruel villain, and a tragic and sympathetic outsider. (pp. 10–11)

[286]Traditional portrayals of Shylock have been explored by contemporary actors, including Patrick Stewart. Stewart was interviewed (Shakespeare Teaching Videos, 2014) in 1978, where he reflected on his experience: “It was a role essentially fixed in two interpretations . . . one is the murderous, wolfish, bloodthirsty, dog Jew, and the other is the noble, suffering, dignified member of a persecuted race” The binary that Stewart draws is fertile ground for discussion, which students can engage in after watching the interview. One potential avenue for exploration is to ask students to challenge these two fixed interpretations and consider other ways to play Shylock. To further open this conversation, have students mix up and reinvent some of the production decisions (see Cahalan’s chapter on casting in this volume); e.g., an all-female cast, set in a refugee camp in Greece, etc.

In the mid-1980s, The Royal Shakespeare Company’s Playing Shakespeare series hosted a similar conversation with David Suchet and Patrick Stewart (Bracksieck, 2011). The actors discuss their differing approaches to playing Shylock, addressing the play’s antisemitism. Stewart reflects on the “antisemitic reverberations” in the play and argues these cannot be avoided or underplayed. This conversation between actors opens up powerful lines of classroom inquiry about how contemporary audiences interpret texts produced centuries ago and what responsibilities modern theater producers and actors have to both[287] fidelity to the text and their contemporary audience’s worldviews and experiences.

Teachers can also compare and contrast other actors’ portrayals, including Al Pacino’s (ROMEje1408, 2013) and Paterson Joseph’s (Guardian Culture, 2016).

Day 5—Contemporary Reactions and Interpretations

The goal is to present students with contemporary concerns and critiques of plays and spark discussion. This lesson builds off the previous lesson by raising arguments about the play’s role in contemporary culture. The lesson can be adapted for other plays; however, the debate around MoV is critically poignant in ways that few other plays are.

Below (included) is a list of articles, op-eds, and podcasts. A possible technique for this lesson is using a Jigsaw activity (Aronson et al., 1978), beginning with assigning students one article to analyze rhetorically. Guide students to deconstruct and analyze the author’s argument in the article, which students will share with their peers in the Jigsaw. After students have completed their rhetorical analysis of the article, have them form groups of four with students who have each read a different article. Each student will present their article while their group members take notes. After everyone has shared, have students discuss which ideas most resonate with them and why. After students explore their own opinions with their Jigsaw groups, open up the floor to whole-class discussion. Teachers can also close the class with written reflections: Should MoV still be produced for theater? If so, what considerations should directors and actors make for modern audiences?[288]

- The Washington Post’s “‘The Merchant of Venice’ Perpetuates Vile Stereotypes of Jews. So Why Do We Still Produce It?” (Franks, 2016)

- Smithsonian Magazine’s “Four Hundred Years Later, Scholars Still Debate Whether Shakespeare’s ‘Merchant of Venice’ Is Anti-Semitic” (Ambrosino, 2016)

- The New York Times’s “Debate over Shylock Simmers Once Again” (Kakutani, 1981)

- The New York Times’s “THEATER; Shylock and Nazi Propaganda” (Gross, 1993)

- The New York Times’s “A Museum Tackles Myths About Jews and Money”(Nayeri, 2019)

- NPR’s “New ‘Merchant Of Venice’ Recasts Shylock as a Sympathetic Everyman” (NPR, 2016)

- NPR Code Switch’s “All That Glisters Is Not Gold” (Demby & Meraji, 2019)[2]

Day 6—Creating Your Own Multimodal Text

To close the mini-unit, provide students the opportunity to create their own multimodal text that extends their exploration of the mini-unit’s central ideas. Ideas include the following:

- Design the stage for the play; it could be 2D, 3D, or rendered on the computer if students have the technology (This could even be done in Minecraft)

- Cast the play. (See Cahalan’s chapter in this volume for more ideas)

- Create a video production of a scene

- Create a podcast

Creating multimodal texts can be challenging for students as they may have never worked in these genres before. Mentor text analysis—where[289] students study the text features of several mentor texts to identify key characteristics of the text, including genre conventions, affordances, and constraints—is recommended for guiding students into text construction. Mentor text analysis helps anchor student awareness in the genre’s text features and gets them thinking about what goes into creating a text of their own.

Closing Comments

This mini-unit highlights how multimodal texts can be transmediated to strengthen the social construction of knowledge and support classroom inquiry. When students are exposed to multiple texts in a range of media, they are exposed to more voices, more ideas, and more ways to make meaning. Each text interaction is enriched by the text interaction preceding it, building from one multimodal text to another, all the while tapping into students’ personal knowledge and experiences. In these ways, multimodal transmediation challenges canonical interpretations by privileging student perspective and insight as part of an expanded repertoire of resources for critical meaning-making.

References

Ambrosino, B. (2016, April 21). Four hundred years later, scholars still debate whether Shakespeare’s “Merchant of Venice” is anti-semitic. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/why-scholars-still-debate-whether-or-not-shakespeares-merchant-venice-anti-semitic-180958867/

Anti-Defamation League (ADL). (2006). Anti-semitism and The Merchant of Venice: A discussion guide. https://www.adl.org/media/9390/download

Aronson, E., Blaney, N., Stephin, C., Sikes, J., & Snapp, M. (1978). The jigsaw classroom. Sage.[290]

Barnes, D. (1992). From communication to curriculum. Boynton/Cook Heinemann. (Original work published 1976)

BBC. (2011, May 17). Shakespeare, “The Merchant of Venice”, act 3 scene 1, Shylock: “To bait fish withal”—BBC [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/FC8KMnC3O_4?si=F0XGP7K_29o4HQrS

Bordalejo, B. (2021, January 21-23). Non-zero-sum: Diverse knowledge perspectives in academia [Presentation]. RaceB4Race (RB4R) Conference, Online.

Bracksieck, M. [@mbracksieck]. (2011, September 20). Shylock-actors-disscuss.mpg [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/FU_zq BIITDM?si= sO7RyAY56IbetSdD

Demby, G., & Meraji, S. M. (Hosts). (2019, August 20). All that glisters is not gold [Audio podcast episode]. In Code switch. NPR. https://www.npr.org/transcripts/752850055

Frank, S. (2016, July 28). “The Merchant of Venice” perpetuates vile stereotypes of Jews. So why do we still produce it? Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2016/07/28/stop-producing-the-merchant-of-venice/

Gross, J. (1993, April 4). Theatre; Shylock and Nazi propaganda. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1993/04/04/theater/theater-shylock-and-nazi-propaganda.html

Guardian Culture [@guardianculture]. (2016, May 5). Paterson Joseph as Shylock: “You call me misbeliever” | Shakespeare solos [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/-vSR6W8_uBU?si=2hVN6pBRF1XqQmnL

Harste, J. (2000). Six points of departure. In B. Berghoff, K. Egawa, J. Harste, & B. Hoonan (Eds.), Beyond reading and writing: Inquiry, curriculum, and multiple ways of knowing (pp. 1–16). National Council of Teachers of English.

Innis, R. (Ed.). (1985). Semiotics: An introductory anthology. Indiana University Press.

Kakutani, M. (1981, February 22). Debate over Shylock simmers once again. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/02/22/theater/debate-over-shylock-simmers-once-again.html

Magee, P., & Leeth, J. (2014). Using transmediation in elementary preservice teacher education. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 58(4), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.364

McCormick, J. (2011). Transmediation in the language arts classroom: Creating contexts for analysis and ambiguity. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 54(8), 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.54.8.3

Mehdizadeh, N. (2021, January 21-23). Teaching the travail of writing: Authority, empire, and racial formation in the (pre)modern [Presentation]. RaceB4Race (RB4R) Conference, Online.

Nayeri, F. (2019, March 20). A museum tackles myths about Jews and money. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/20/arts/design/jews-money-myth-antisemitism-exhibition-london.html

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–92. https:// doi.org/10.17763/haer.66.1.17370n67v22j160u

NPR. (2016, July 29). New “Merchant of Venice” recasts Shylock as a sympathetic Everyman. https://tinyurl.com/49nbfkjb

ROMEje1408 [@ROMEje1408]. (2013, May 22). The Merchant of Venice 2004 Shylock speech) HD [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/th7 euZ30wDE?si=8-OEdFx_O-htJPo8

Shakespeare, W. (n.d.). The Merchant of Venice (Act 3, Scene 1). In MIT’s Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Retrieved October 22, 2022, from https://shakespeare.mit.edu/merchant/merchant.3.1.html

Shakespeare Teaching Videos [@shakespeareteachingvideos2238]. (2014, March 14). Patrick Stewart on Shylock [Video]. YouTube. https:// youtu.be/7UOdMHW7J2Q?si=orQYfey90cPuirKJ

Siegel, M. (1995). More than words: The generative power of transmediation for learning. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue Canadienne de l’éducation, 20(4), 455–475.

Siegel, M. (2006). Rereading the signs: Multimodal transformations in the field of literacy education. Review of Research, 84(1), 65–77.

Smith, B. E. (2019). Mediational modalities: Adolescents collaboratively interpreting literature through digital multimodal composing. Research in the Teaching of English, 53(3), 197–222. https://doi.org/10.58680/rte201930034

Suhor, C. (1984). Towards a semiotics‐based curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 16 (3), 247–257.

- Common Core State Standards for eleventh- and twelfth-grade Reading, in the subtheme “Integration of Knowledge and Ideas.” The learning objective is: Analyze multiple interpretations of a story, drama, or poem (e.g., recorded or live production of a play or recorded novel or poetry), evaluating how each version interprets the source text. (Include at least one play by Shakespeare and one play by an American dramatist.) ↵

- A note about the podcasts: include the podcasts in the Jigsaw activity or have students listen to the podcasts before reading the articles as an anticipatory activity. Listening can be done with the whole class or independently if students have headphones and personal electronic devices. ↵